Tour de France winners

Every winner of the Tour de France from 1903 onwards

- Sign up to our newsletter Newsletter

The roll-call of Tour de France winners contains the names of many of the world's best bike riders through time.

The most illustrious of the three Grand Tours, the Tour de France has been taking place on an annual bases since 1903 - with two breaks in its history, one for each of the World Wars.

The most prolific winner would have been Lance Armstrong, who wore the yellow jersey in Paris for seven consecutive years between 1999 and 2005. However, he was stripped of all of his titles in 2012 following investigation by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA).

Next in line, we have a prolific quartet of Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain. All four have five titles to their names, Anquitel was the first to do it but Mercx is still the only person to have won the general, points and king of the mountains classifications in the same Tour - a feat he accomplished in 1969.

Chris Froome (now Israel Start-Up Nation) has four wins to his name - he won in in 2013 and then consecutively from 2015 to 2017 but hasn't managed to equal the record of five overall victories yet.

Tour de France titles won between 1999-2005 were formerly allocated to Lance Armstrong (USA) but stripped after he was found guilty of doping. No alternative winner has been announced for these years.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

How do you win the Tour de France?

In the first ever edition of the race, the winner of the General Classification earned their place based on overall riding time. However, following the disqualification of its 1904 victor, Maurice Garin, the organisers introduced a points based system.

Then, in 1912 they reverted back to awarding the win based on time. This remains the case today - the rider with the lowest overall accumulated time leads the General Classification and whoever holds that position once the peloton arrives in Paris is crowned the winner.

Youngest ever Tour de France winner

Henri Cornet, 19-years-old

Oldest ever Tour de France winner

Firmin Lambot, 36-years-old

First Tour de France winner

The first ever win went to a rider from the race's home country - Maurice Garin, in 1903.

First ever Tour de France GC disqualification

Also Garin. The Frenchman also won in 1904, however he was disqualified for allegedly using means of transport outside of the bicycle (car, rail).

The result was that Henri Cornet took his place, and at 19-years-old he will no doubt remain the youngest ever for a long time, if not indefinitely.

There have been quite a few disqualifications since, mostly for doping (Armstrong, 1999-2005, Floyd Landis, 2006, Alberto Contador, 2010).

First non-French Tour de France winner

The winner's list for the early years of the race is dominated by Frenchman. The first winner from outside the country of origin was 1909 leader François Faber of Luxembourg.

Britain took a while to catch up - the first British rider of the men's Tour de France race was Bradley Wiggins (Team Sky) in 2012. GB now have five overall victories to their name thanks to Wiggins and Froome.

Smallest ever winning margin

In 1989, American Greg LeMond won over Laurent Fignon by just eight seconds.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Hi, I'm one of Cycling Weekly's content writers for the web team responsible for writing stories on racing, tech, updating evergreen pages as well as the weekly email newsletter. Proud Yorkshireman from the UK's answer to Flanders, Calderdale, go check out the cobbled climbs!

I started watching cycling back in 2010, before all the hype around London 2012 and Bradley Wiggins at the Tour de France. In fact, it was Alberto Contador and Andy Schleck's battle in the fog up the Tourmalet on stage 17 of the Tour de France.

It took me a few more years to get into the journalism side of things, but I had a good idea I wanted to get into cycling journalism by the end of year nine at school and started doing voluntary work soon after. This got me a chance to go to the London Six Days, Tour de Yorkshire and the Tour of Britain to name a few before eventually joining Eurosport's online team while I was at uni, where I studied journalism. Eurosport gave me the opportunity to work at the world championships in Harrogate back in the awful weather.

After various bar jobs, I managed to get my way into Cycling Weekly in late February of 2020 where I mostly write about racing and everything around that as it's what I specialise in but don't be surprised to see my name on other news stories.

When not writing stories for the site, I don't really switch off my cycling side as I watch every race that is televised as well as being a rider myself and a regular user of the game Pro Cycling Manager. Maybe too regular.

My bike is a well used Specialized Tarmac SL4 when out on my local roads back in West Yorkshire as well as in northern Hampshire with the hills and mountains being my preferred terrain.

The FDJ-SUEZ rider finally takes the victory at La Doyenne after finishing runner-up in 2020 and 2022

By Joseph Lycett Published 21 April 24

The UAE Team Emirates rider takes his sixth Monument victory at La Doyenne

Useful links

- Tour de France

- Giro d'Italia

- Vuelta a España

Buyer's Guides

- Best road bikes

- Best gravel bikes

- Best smart turbo trainers

- Best cycling computers

- Editor's Choice

- Bike Reviews

- Component Reviews

- Clothing Reviews

- Contact Future's experts

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Advertise with us

Cycling Weekly is part of Future plc, an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate site . © Future Publishing Limited Quay House, The Ambury, Bath BA1 1UA. All rights reserved. England and Wales company registration number 2008885.

Official games

2023 Edition

- Stage winners

- All the videos

Tour Culture

- Commitments

- key figures

- Sporting Stakes

- "Maillot Jaune" Collection

- The jerseys

1940: The Tour that wasn’t (4/10)

At the turn of each decade, the Tour de France has gone through organisational changes and backstage struggles that have variously turned out to be decisive or utterly inconsequential. The journey back in time proposed by letour.fr continues in 1940: when the country entered the war, Henri Desgrange tried to keep the 34th edition of the Tour alive until spring, but had to resign himself to its cancellation. Before July France was already under German occupation, and Desgrange left the Tour orphaned in August.

According to the tautological principle that you can't suppress something that doesn't exist, the 1940 edition of the Tour de France is the only one in history to have been cancelled. Although its detailed route was never published and its dates were not officially announced, its organisation was well thought out, envisaged and programmed in the offices of the organising newspaper, in a France that was nevertheless at war and whose youth had been drafted in September 1939. It would be far-fetched to suspect L'Auto of existing naively in a sports bubble ignoring the major issues in the balance on the battlefield, quite the contrary. From mid-September, the newspaper even assumed a total commitment by changing its title to L'Auto-Soldat, and its editorial line then split between news of the world conflict, analysis of the competitions that continued to take place and news of the champions called up to serve in the armed forces. On 16 September, the headline was accompanied by an unequivocal quote from Voltaire: "Every man is a soldier against tyranny". It is in this line that Henri Desgrange, who, although seriously ill, did not let go of his pen but distanced himself from sport, multiplied patriotic editorials and caricatures, for example Hitler, whom he described as a "house painter" . In its services, all the assistants were active and strove to give shape from the very beginning of winter to a cycling season that could also sustain the idea that France continued to live on. In December, discussions began with the heads of the bicycle manufacturers to try to come up with a calendar and invent a new formula. How can a bunch of riders of at the same skill level be formed when most of the riders in the 1939 Tour were fighting? Were foreign cyclists from non-belligerent countries going to be accepted? Who would therefore have their best people available? Where can we get bicycles when the entire industry is focused on the war effort? The debate was launched, and even initiated in the columns of the newspaper, which transcribed the content of the negotiations like a soap opera. Alcyon's boss was optimistic, but not as determined as Colibri's: "I've come, like all my colleagues, to put a white ball in to get unanimous congratulations," read the 16 January edition of L'Auto. On the other hand, Genial-Lucifer had more misgivings ( "Maurice Evrard felt that in his own opinion the uselessness of certain road races was obvious" , L'Auto of 13 January), and the tone was also very cautious from the head of Dilecta. However, we manage to get everyone to agree year after year on a formula published on 6 February which, among other measures, only admits riders who are not yet old enough to carry weapons and limits the number of foreigners to 33% of the peloton. On 11 July, on the BBC, an anonymous columnist chose sport to make the voice of London heard. "Today, if Mr. Hitler had agreed to let Europe live in peace, he would have set off joyfully on the 34th Tour de France.” Everything seemed more or less in place, but while it was business as usual at the velodromes throughout the winter, there were great difficulties at the start of the road racing season. Paris-Roubaix, whose route was initially validated by military authorities, was transformed into Roubaix-Paris and finally saved in-extremis as Le Mans-Paris! It looked like there was also going to be course reversal for Paris-Tours, and the clouds were particularly threatening on the Race to the Sun, which L'Auto was exceptionally associated with the Le Petit Niçois newspaper in an attempt to save the organisation. Above all, Henri Desgrange published a paper with a very pessimistic tone for the future of the 1940 Tour de France. He evoked a course in the form of a "deflated bladder", listed all the constraints he faced, and concluded as follows: "It would be enough, wouldn't it, for you to expect this article to end with the announcement that the 1940 Tour de France will not take place? Well! It is not enough for us and we still have one last hope of being able to triumph over all these difficulties, and we want to give it a try" . The sentence was not long in coming. Four days later, the announcement was posted on the front page: "The Tour de France will not take place this year. It is postponed to 1941. See the explanations provided by its creator, Henri Desgrange, in the 13 and 14 April issues.” Events then precipitated the country into the dark sequence of the German occupation following the signing of the armistice of 22 June 1940 by Philippe Pétain. Meanwhile, Charles De Gaulle launched his 18 June appeal on the BBC, the Free France timidly structured itself behind the "Leader of the French who continue the war". It so happened that from London, the following 11 July, a small French enclave decided to act as if the Tour de France had started. The programme "Ici la France" was broadcast daily for half an hour on the BBC. That day, an anonymous columnist whose name remains unknown chose sport to make the voice of London heard. "Today, if Mr. Hitler had agreed to let Europe live in peace, he would have set off joyfully on the 34th Tour de France" * . A completely fictitious story began, as a way to reunite the divided country and to find itself in a shared and happy wistfulness. This was far from reality, but in the legend of the Tour, the story is as important as the race. It is unlikely that Henri Desgrange could have heard this report, which would have certainly given him chills, perhaps even drawn a few tears. For the 1940 Tour de France, even if it had been able to take place, would also have been the first without him. Operated on a few months earlier and seriously weakened, the father of the Tour de France died on 16 August, at the age of 75. His successor and spiritual son, Jacques Goddet, took over the reins of the newspaper and the following year he opposed the organisation of a Tour de France whose prestige would be claimed by the Vichy regime. The return of the real Tour de France had to wait until 1947. * Source: L’Histoire, number 354, June, 2010. 1940: The Tour de France will not take place. By Marianne Amar To discover or reread, the previous instalments in the series: . 1930: The Tour revolutionizes (3/10) . 1920: The « sportsmen » according to Desgrange (2/10) . 1910: Alphonse Steinès’ great deception (1/10)

You may also enjoy

"Tour de France Cycle City" label: soon 150 towns and 10 countries in the loop?

Tourtel Twist to continue to add zest to the Tour de France

Predict the winner of Liège-Bastogne-Liège

Receive exclusive news about the Tour

Accreditations

Privacy policy, your gdpr rights.

Home > Events > Cycling > Tour de France > Winners > List

Tour de France Winners List

The most successful rider in the Tour de France was Lance Armstrong , who finished first seven times before his wins were removed from the record books after being found guilty of doping by the USADA in 2012. No rider has been named to replace him for those years.

> see also more information about how they determine the winners of the Tour

General Classification Winners

* footnotes

- 1904: The original winner was Maurice Garin, however he was found to have caught a train for part of the race and was disqualified.

- 1996: Bjarne Riis has admitted to the use of doping during the 1996 Tour. The Tour de France organizers have stated they no longer consider him to be the winner, although Union Cycliste Internationale has so far refused to change the official status due to the amount of time passed since his win. Jan Ullrich was placed second.

- 1999-2005: these races were originally won by Lance armstrong, but in 2012 his wins in the tour de france were removed due to doping violations.

- 2006: Floyd Landis was the initial winner but subsequently rubbed out due to a failed drug test.

- 2010: Alberto Contador was the initial winner of the 2010 event, but after a prolonged drug investigation he was stripped of his win in 2012.

Related Pages

- Read how they determine the winners of the Tour

- Tour de France home page.

- Anthropometry of the Tour de France Winners

Search This Site

More cycling.

- Cycling Home

- Fitness Testing

- Tour de France

- Cyclist Profiles

Major Events Extra

The largest sporting event in the world is the Olympic Games , but there are many other multi-sport games . In terms of single sport events, nothing beats the FIFA World Cup . To see what's coming up, check out the calendar of major sporting events .

Latest Pages

- World Friendship Games

- How We Watch Sport

- Sound Reaction Time

- Trisome Games

Current Events

- Kentucky Derby

- French Open

- Paris Olympics

- 2024 Major Events Calendar

Popular Pages

- Super Bowl Winners

- Ballon d'Or Winners

- World Cup Winners

Latest Sports Added

- Wheelchair Cricket

- SUP Jousting

- Virtual Golf

home search sitemap store

SOCIAL MEDIA

newsletter facebook X (twitter )

privacy policy disclaimer copyright

contact author info advertising

Every Tour de France Winner Since 1903

So, you are wondering who every Tour de France winner since the start of the iconic race back in 1903 is? Let's dive in to it!

Although it may not rank amongst the most popular sports in America, the Tour de France remains one of the most historic and anticipated sporting events in the world. It's truly an exhibition of how far the human body can be pushed.

Related : Making Sense of the Tour de France

Since its inception in 1903, the best cyclist and sports scientists in the world take their talent to the beautiful back country of France in an attempt to claim the title of Tour de France champion.

Here is a list of every Tour de France winner:

2022: Jonas Vingegaard

- Country : Denmark

- Team: Jumbo-Visma

The 2022 Tour de France will be one remembered for decades to come. Slovenian cyclist Tadej Pogačar was on the cusp of winning his third straight Tour before Jonas Vingegaard had something to say about it. The race came down to the wire when Pogačar and Vingegaard were neck-and-neck on the Col de Spandelles, even causing a crash that left Pogačar with scratches to his leg. Vingegaard finished in 79 hours, 33 minutes, and 20 seconds, setting a record for fastest finish in Tour history. Without a doubt, Vingegaard will be coming back to defend his title this upcoming Tour de France.

2021: Tadej Pogačar

- Country: Slovenia

- Team: UAE Team Emirates

After a dominating 2020 Tour de France, all eyes were on the twenty-two-year-old cyclist to remain atop the racing mountain. He did that and more in dominating fashion, becoming the youngest racer to ever win two Tour de France titles. Not only did Pogačar take home the yellow shirt, he claimed a victory in the Mountains and Youth classifications.

Pogačar started to build a lead after winning the time trail on stage 5, and gained three and a half minutes on the second place racer by the 8th stage. By the final race day, Pogačar was racing defensively with a fierce lead and an almost guaranteed win.

2020: Tadej Pogačar

Country: Slovenia Team: UAE Team Emirates

With the looming Covid-19 pandemic and the world's sporting events being shutdown, it looked as though the 2020 Tour de France wouldn't happen. After a short postponement, the Tour was back in action and the cycling world was introduced to its newest legend.

Tadej Pogačar went into the 2020 Tour with a modest shot at winning, but almost nobody had him as a general favorite to win. He proved everyone wrong and became the first Slovenian born cyclist to win the Tour. Pogačar also claimed wins in the Mountains and Youth classifications, cementing himself as the best all-around cyclist in the world as of now.

2019: Egan Bernal

- Country: Colombia

- Team: Ineos

The 2019 Tour de France gave us another cyclist claiming their home countries first title after Egan Bernal won in dominating fashion. Team Ineos had such a dominant performance that their racers finished in first and second place, claiming them the team championship as well. Bernal finished the Tour in eighty-two hours and fifty-seven minutes, a whole minute and eleven seconds above second.

2018: Geraint Thomas

- Country: Great Britain

Not only was 2018 an incredibly dominant year for Geraint Thomas, but it was just as great for racing team Sky. The 2018 Tour marked the fourth straight competition that saw a racer from team Sky claim the yellow shirt. Although Thomas didn't dominate the race at every stage, he carefully chose his moments to make pushes and gain time, eventually putting him in first. Thomas won no other classifications this year, but that doesn't matter when you're wearing the yellow shirt.

Every Winner Since 2018

- 2017: Chris Froome, Great Britain

- 2016: Chris Froome, Great Britain

- 2015: Chris Froome, Great Britain

- 2014: Vincenzo Nibali, Italy

- 2013: Chris Froome, Great Britain

- 2012: Bradley Wiggins, Great Britain

- 2011: Cadel Evans, Australia

- 2010: Andy Schleck, Luxembourg

- 2009: Alberto Contador, Spain

- 2008: Carlos Sastre, Spain

- 2007: Alberto Contador, Spain

- 2006: Óscar Pereiro, Spain

- 2005-1999: (Lance Armstrong stripped of titles due to doping)

- 1998: Marco Pantani, Italy

- 1997: Jan Ullrich, Germany

- 1996: Bjarne Riis, Denmark

- 1995: Miguel Indurain, Spain

- 1994: Miguel Indurain, Spain

- 1993: Miguel Indurain, Spain

- 1992: Miguel Indurain, Spain

- 1991: Miguel Indurain, Spain

- 1990: Greg LeMond, United States

- 1989: Greg LeMond, United States

- 1988: Pedro Delgado, Spain

- 1987: Stephen Roche, Ireland

- 1986: Greg LeMond, United States

- 1985: Bernard Hinault, France

- 1984: Laurent Fignon, France

- 1983: Laurent Fignon, France

- 1982: Bernard Hinault, France

- 1981: Bernard Hinault, France

- 1980: Joop Zoetemelk, Netherlands

- 1979: Bernard Hinault, France

- 1978: Bernard Hinault, France

- 1977: Bernard Thévenet, France

- 1976: Lucien Van Impe, Belgium

- 1975: Bernard Thévenet, France

- 1974: Eddy Merckx, Belgium

- 1973: Luis Ocaña, Spain

- 1972: Eddy Merckx, Belgium

- 1971: Eddy Merckx, Belgium

- 1970: Eddy Merckx, Belgium

- 1969: Eddy Merckx, Belgium

- 1968: Jan Janssen, Netherlands

- 1967: Roger Pingeon, France

- 1966: Lucian Aimar, France

- 1965: Felice Gimondi, Italy

- 1964: Jacques Anquetil, France

- 1963: Jacques Anquetil, France

- 1962: Jacques Anquetil, France

- 1961: Jacques Anquetil, France

- 1960: Gastone Nencini, Italy

- 1959: Federico Bahanontes, Spain

- 1958: Charly Gaul, Luxembourg

- 1957: Jacques Anquetil, France

- 1956: Roger Walkowiak, France

- 1955: Louison Bobet, France

- 1954: Louison Bobet, France

- 1953: Louison Bobet, France

- 1952: Fausto Coppi, Italy

- 1951: Hugo Koblet, Switzerland

- 1950: Ferdinand Kübler, Switzerland

- 1949: Fausto Coppi, Italy

- 1948: Gino Bartali, Italy

- 1947: Jean Robic, France

- 1946-1940: (No race due to World War II)

- 1939: Sylvère Maes, Belgium

- 1938: Gino Bartali, Italy

- 1937: Roger Lapébie, France

- 1936: Sylvère Maes, Belgium

- 1935: Romain Maes, Belgium

- 1934: Antonin Magne, France

- 1933: Georges Speicher, France

- 1932: André Leducq, France

- 1931: Antonin Magne, France

- 1930: André Leducq, France

- 1929: Maurice De Waele, Belgium

- 1928: Nicolas Frantz, Luxembourg

- 1927: Nicolas Frantz, Luxembourg

- 1926: Lucien Buysse, Belgium

- 1925: Ottavio Bottecchia, Italy

- 1924: Ottavio Bottecchia, Italy

- 1923: Henri Pélissier, France

- 1922: Firmin Lambot, Belgium

- 1921: Léon Scieur, Belgium

- 1920: Philippe Thys, Belgium

- 1919: Frimin Lambot, Belgium

- 1918-1915: ( No race due to World War I)

- 1914: Philippe Thys, Belgium

- 1913: Philippe Thys, Belgium

- 1912: Odile Defraye, Belgium

- 1911: Gustave Garrigou, France

- 1910: Octave Lapize, France

- 1909: François Faber, Luxembourg

- 1908: Lucien Petit-Breton, France

- 1907: Lucien Petit-Breton, France

- 1906: René Pottier, France

- 1905: Louis Trousselier, France

- 1904: Henri Cornet, France

- 1903: Maurice Garin, France

For more sports content:

Which NFL Team Has the Most Super Bowl Wins?

Lifting Lord Stanley: Most Stanley Cups in NHL History

Who Has the Most NBA Championships?

Tour de France winners

Past winners of the Tour de France:

2010 -- Alberto Contador, Spain 2009 -- Alberto Contador, Spain 2008 -- Carlos Sastre, Spain 2007 -- Alberto Contador, Spain 2006 -- Oscar Pereiro, Spain-* (*-Pereiro was named the Tour winner after Floyd Landis was stripped of the title after a positive doping test. 2005 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* 2004 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* 2003 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* 2002 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* 2001 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* 2000 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* 1999 -- Lance Armstrong, United States-* (*-Armstrong's seven titles were stripped and vacated after UCI upheld the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency's ruling against the cyclist.) 1998 -- Marco Pantani, Italy 1997 -- Jan Ullrich, Germany 1996 -- Bjarne Riis, Denmark 1995 -- Miguel Indurain, Spain 1994 -- Miguel Indurain, Spain 1993 -- Miguel Indurain, Spain 1992 -- Miguel Indurain, Spain 1991 -- Miguel Indurain, Spain 1990 -- Greg LeMond, United States 1989 -- Greg LeMond, United States 1988 -- Pedro Delgado, Spain 1987 -- Stephen Roche, Ireland 1986 -- Greg LeMond, United States 1985 -- Bernard Hinault, France 1984 -- Laurent Fignon, France 1983 -- Laurent Fignon, France 1982 -- Bernard Hinault, France 1981 -- Bernard Hinault, France 1980 -- Joop Zoetemelk, Netherlands 1979 -- Bernard Hinault, France 1978 -- Bernard Hinault, France 1977 -- Bernard Thevenet, France 1976 -- Lucien Van Impe, Belgium 1975 -- Bernard Thevenet, France 1974 -- Eddy Merckx, Belgium 1973 -- Luis Ocana, Spain 1972 -- Eddy Merckx, Belgium 1971 -- Eddy Merckx, Belgium 1970 -- Eddy Merckx, Belgium 1969 -- Eddy Merckx, Belgium 1968 -- Jan Jansen, Netherlands 1967 -- Roger Pingeon, France 1966 -- Lucian Almar, France 1965 -- Felice Gimondi, Italy 1964 -- Jacques Anquetil, France 1963 -- Jacques Anquetil, France 1962 -- Jacques Anquetil, France 1961 -- Jacques Anquetil, France 1960 -- Gastone Nencini, Italy 1959 -- Federico Bahamontes, Spain 1958 -- Charly Gaul, Luxembourg 1957 -- Jacques Anquetil, France 1956 -- Roger Walkowiak, France 1955 -- Louison Bobet, France 1954 -- Louison Bobet, France 1953 -- Louison Bobet, France 1952 -- Fausto Coppi, Italy 1951 -- Hugo Koblet, Switzerland 1950 -- Ferdinand Kubler, Switzerland 1949 -- Fausto Coppi, Italy 1948 -- Gino Bartali, Italy 1947 -- Jean Robic, France 1940-46 -- Tour cancelled, World War II 1939 -- Sylvare Maes, Belgium 1938 -- Gino Bartali, Italy 1937 -- Roger Lapeble, France 1936 -- Sylvere Maes, Belgium 1935 -- Romain Maes, Belgium 1934 -- Antonin Magne, France 1933 -- Georges Speicher, France 1932 -- Andre Leducq, France 1931 -- Antonin Magne, France 1930 -- Andre Leducq, France 1929 -- Maurice Dewsele, Belgium 1928 -- Nicholas Frantz, Luxembourg 1927 -- Nicholas Frantz, Luxembourg 1926 -- Lucian Bruysee, Belgium 1925 -- Ottavio Bottecchia, Italy 1924 -- Ottavio Bottecchia, Italy 1923 -- Henri Pellissier, France 1922 -- Firmin Lambot, Belgium 1921 -- Leon Scieur, France 1920 -- Phillipe Thys, Belgium 1919 -- Firmin Lambot, Belgium 1915-18 -- Tour cancelled, World War I 1914 -- Phillipe Thys, Belgium 1913 -- Phillipe Thys, Belgium 1912 -- Odile Defraye, Belgium 1911 -- Gustave Farrigou, France 1910 -- Octave Lapize, France 1909 -- Francois Faber, Luxembourg 1908 -- Lucien Petit-Breton, France 1907 -- Lucien Petit-Breton, France 1906 -- Rene Pottier, France 1905 -- Louis Trousseller, France 1904 -- Henri Cornet, France 1903 -- Maurice Garin, France

Tour de France past winners

A full list of champions from 1903 – 2021

Previous overall and classification winners

1 Tadej Pogacar (Slo) UAE Team Emirates 2 Jonas Vingegaard (Den) Jumbo-Visma 3 Richard Carapaz (Ecu) Ineos Grenadiers

2020 1 Tadej Pogacar (Slo) UAE Team Emirates 2 Primoz Roglic (Slo) Team Jumbo-Visma 3 Richie Porte (Aus) Trek-Segafredo

2019 1 Egan Bernal (Col) Team Ineos 2 Geraint Thomas (GBr) Team Ineos 3 Steven Kruijswijk (Ned) Team Jumbo-Visma

2018 1 Geraint Thomas (GBr) Team Sky 2 Tom Dumoulin (Ned) Team Sunweb 3 Chris Froome (GBr) Team Sky

2017 1 Christopher Froome (GBr) Team Sky 2 Rigoberto Uran (Col) Cannondale-Drapac 3 Romain Bardet (Fra) AG2R-La Mondiale

2016 1 Christopher Froome (GBr) Team Sky 2 Romain Bardet (Fra) AG2R-La Mondiale 3 Nairo Alexander Quintana Rojas (Col) Movistar Team

2015 1 Christopher Froome (GBr) Team Sky 2 Nairo Quintana (Col) Movistar Team 3 Alejandro Valverde (Spa) Movistar Team

2014 1 Vincenzo Nibali (Ita) Astana Pro Team 2 Jean-Christophe Péraud (Fra) AG2R-La Mondiale 3 Thibaut Pinot (Fra) FDJ.fr

2013 1 Christopher Froome (GBr) Sky Procycling 2 Nairo Alexander Quintana Rojas (Col) Movistar Team 3 Joaquim Rodriguez Oliver (Spa) Katusha

2012 1 Bradley Wiggins (GBr) Sky Procycling 2 Christopher Froome (GBr) Sky Procycling 3 Vincenzo Nibali (Ita) Liquigas-Cannondale

2011 1 Cadel Evans (Aus) BMC Racing Team 2 Andy Schleck (Lux) Leopard Trek 3 Frank Schleck (Lux) Leopard Trek

2010 1 *Andy Schleck (Lux) Team Saxo Bank 2 Denis Menchov (Rus) Rabobank 3 Samuel Sánchez Gonzalez (Spa) Euskaltel - Euskadi

2009 1 Alberto Contador Velasco (Spa) Astana 2 Andy Schleck (Lux) Team Saxo Bank 3 Lance Armstrong (USA) Astana

Note: *Andy Schleck was awarded victory of the 2010 Tour de France after original winner Alberto Contador was disqualified for doping. *Lance Armstrong was stripped of all race results from August 1, 1998 onwards following the US Anti-Doping Agency’s investigation into doping at the US Postal Service team. *Austria's Bernhard Kohl tested positive for EPO-CERA on October 13, 2008. He admitted to its use on October 15, 2008 and was stripped of his third place GC finish at the 2008 Tour de France. *Oscar Pereiro was awarded the victory of the 2006 Tour de France on October 16, 2007, after original winner Floyd Landis was disqualified for doping.

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Vuelta a Burgos Feminas - Past Winners 2024

Tour de Romandie past winners

Pogačar, UAE Team Emirates top UCI rankings, Astana losing fight against relegation

Most popular, latest on cyclingnews.

Wiebes, Vollering aiming for Tour de France Femmes repeat on home soil

The Pogacar Premium? Colnago bucks the market trend and triples turnover in three years

Ruth Edwards seals two-year extension with Human Powered Health

The Tour de France Winner Who Used His Bicycle to Help Save Hundreds of Jews During WWII

I n 1938 Gino Bartali won the Tour de France and became one of the most famous athletes in Europe. It should have been a triumph—not only for him, but for Benito Mussolini and his Fascist regime. Sports were incredibly important to Il Duce, who is said to have proclaimed his intention to turn Italy from a nation of mandolin players into one of warriors. The propaganda machine showed Mussolini himself as a great sportsman. He encouraged participation in athletics of all kinds and closely managed physical fitness for schoolchildren. Now, in cycling-obsessed Italy, Mussolini desperately wanted victory at the Tour, the sport’s most prestigious event. Italian fans flocked to France to cheer on their countryman Bartali as he stormed through the brutal climbs in the Alps and Pyrenees. On July 31 he crossed the finish line in the famed yellow jersey of the leader. In Paris “the ovations were not only directed at the triumphant one of the Tour de France,” the Gazetta dello Sport proclaimed. “They were exalting the athletic and moral virtue of an exemplar of our race.”

But unlike other Italian champions, Bartali did not dedicate his victory to Il Duce. Largely apolitical and a devout Catholic, he was instead loyal to the church. Bartali opposed fascist doctrine and did not want to present himself as an Aryan champion. “They always tried to show off what he did as proof of what fascism could do,” one of his teammates noted. “But Bartali wouldn’t cooperate.” On Italian radio, Mussolini’s secret police complained, he “mumbled” rather than offer praise to the government. On the French radio, he merely thanked his fans. The next day, trailed by the press, Bartali went to mass at Notre-Dame-des-Victoires and laid his victory wreath at the feet of the Madonna.

The slight did not go unnoticed by Mussolini. A French cycling magazine sent a reporter to cover what it assumed would be a rapturous homecoming. “Not a cat at the train station. No organized reception. Nothing. I don’t understand,” the journalist wrote. “An Italian wins the Tour de France, he wins a sensational international victory and his compatriots—who are Latins prone to delirious joy—don’t react much at all? There’s a problem.” Mussolini canceled a special medal ceremony, and the head of the Italian Cycling Federation did not attend Bartali’s victory lap at the velodrome in Turin. The Ufficio Stampa, the official press office, gave its instructions: “The newspapers should cover Bartali exclusively as a sportsman.”

During the 1938 Tour, the first legal persecution of Italy’s Jews emerged. In May, Hitler had visited Mussolini to much fanfare, making a whirlwind tour of Italy. The dictators had not always been allies, but had re- cently collaborated during the Spanish Civil War, with Il Duce declaring that their relationship would be the “axis” around which Europe would revolve. After Mussolini visited Germany in 1937, the führer decided to reciprocate just weeks after the annexation of Austria. “Now no force can ever separate us,” Mussolini told him when they said goodbye at the train station.

In retrospect, it would be a turning point for the Jews of Italy. Many Jews had fought for Italian unification and were well incorporated into Italian society. Indeed, Mussolini had previously publicly criticized the Nazis’ anti-Semitism. But now, with Germany in the ascendant, Mussolini moved to ingratiate himself with Hitler. On the day of Bartali’s triumph in the Pyrenees, the government published the Manifesto of the Racial Scientists , declaring that Italians were Aryan, and that Jews did not belong to the Italian race. It was an ominous moment for the forty-seven thousand Italian Jews and the ten thousand others who had fled there from elsewhere. The manifesto heralded the introduction of a series of anti-Jewish laws during the next months. The Fascist Grand Council stripped Jews who had arrived after 1919 of their citizenship, prohibited all Jews from certain professions or from owning property over a certain value, and banned Jewish children from public schools. Especially in the north, anti-Semitism became rampant. Signs declared Jews and dogs not welcome in stores and cafés, and Jews were banned from parks, sports facilities, and other recreational establishments. But while foreign Jews were interned, no Jews were rounded up or deported by the Italians.

After the beginning of the Second World War in 1939, Bartali’s life became a strange combination of bicycle messenger work for the military, domestic life, and competition for several years. But after the Allies invaded North Africa at the end of 1942, the tide of the war began to shift in western Europe. Then just after midnight on July 10, 1943, Allied forces landed in Sicily, and on July 25, the day after a no-confidence vote against Mussolini by the Fascist Grand Council, King Victor Emmanuel III announced that he had arrested the dictator as he left the royal residence. Crowds celebrated everywhere. On September 3 Allied troops landed on the mainland, and five days later the new government under Marshal Pietro Badoglio signed an armistice, surrendering. Italians throughout the country again cheered. Bartali filed his discharge papers, looking forward to leaving the military for good.

The jubilation was short-lived. Two days later, Germans troops occupied Rome, Naples, and northern Italy, reinstating Mussolini in that region as a puppet, and the king fled south to Brindisi. The arrival of the Germans brought a new level of peril to the forty-three thousand Jews, both Italian and foreign, trapped in northern Italy. In November the Fascists formalized the Carta di Verona , which essentially declared Jews enemies of the state. This was not mere discrimination; Jews were now in mortal danger of deportation.

During the occupation, Bartali quietly hid a Jewish married couple he knew slightly and their ten-year-old son and six-year-old daughter in the basement of an apartment he owned in Florence.

“The Germans were killing everybody who was hiding Jews,” the little boy Giorgio Goldenberg recalled. “[Bartali] was risking not only his life, but also his family.” And it would not be just the Goldenbergs. One day Bartali was at his cousin Armando Sizzi’s bike shop on Via Pietrapiana, not far from the synagogue, when there was a roundup. Bartali and Sizzi rushed outside, pushed several people who were fleeing into the store, and quickly pulled down the rolling metal shutters. When night fell, most made their way home, but two remained. One was Jewish. The other was a Romani—subject to similar persecution by the Nazis—who had fallen in love with a Florentine woman. They were both terrified to leave. Bartali and Sizzi allowed them to remain there until the liberation, bringing food and hiding the entrance by parking bicycles in front of the door.

It is likely that when he began hiding people, Bartali had already gotten involved in broader efforts to help Jews and others running for their lives. Prior to the German’ occupation, much of the work of dealing with the influx of foreign refugees in Italy had been handled by the Delegation for the Assistance of Jewish Emigrants (DELASEM). Established by Jews based in Genoa, DELASEM was supported by donations from overseas, particularly from the American Jewish community, and was authorized by the government, which was pleased to both delegate the humanitarian issue and take a commission on all funds the organization raised.

But in 1943 DELASEM’s Jewish leadership was forced under-ground, and many of its members were arrested. They turned to the cardinal of Genoa, Pietro Boetto, who essentially had the church take over its activities. A clandestine network of church officials quickly developed throughout northern Italy, not only providing financial support to Jews but helping to hide them or smuggle them out of the occupied zone.

The seventy-one-year-old archbishop of Florience Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa was the leader of the effort for the church in Florence, where he had been approached by the local Jewish communityOrders were given to the diocese’s convents to open their doors to Jewish women and children, and a number of priests also hid Jews in churches and orphanages. The cardinal led by example and himself hid Jews on the run in his home, just as Bartali was doing. Meetings of the underground were also hosted in an archbishopric palace at Via Pucci, 2, where in November 1943, the local chief rabbi and a Catholic priest were arrested during a raid.

At around this time, Padre Rufino Salvatore Niccacci, the thirty-two-year-old father superior of the San Damiano monastery in Assisi, met with Dalla Costa to discuss the plight of some Jews who had fled there. Giuseppe Placido Nicolini, the Benedictine archbishop of Assisi, had instructed Niccacci and Father Aldo Brunacci to help hide Jews and others who had fled to Assisi. This legendary home of Saint Francis 120 miles north of Rome had a population of just five thousand, including a thousand monks, nuns, and priests, and received over two hundred thousand pilgrims a year. Though Niccacci had never seen a Jew before—indeed it was said that no Jew had ever lived in Assisi—he threw himself fully into the task. Brunacci and Niccacci arranged for clothing, housing in twenty-six convents and monasteries, and false identity papers. Over the course of the war they would hide hundreds of Jews. Not one who came to Assisi was apprehended in the nine months of its occupation.

Routes of escape were becoming more challenging. Dalla Costa explained to Niccacci that he had a group of Jews stranded from Perugia, and over forty thousand more were estimated to be in the northern sector. The Swiss border was now largely sealed, and the Germans kept a close eye on the port of Genoa. The only hope for those on the run was to either stay in hiding for the duration or try to escape to the unoccupied southern zone. Dalla Costa believed that the mountainous areas of Tuscany and Umbria were a good place for Jews and others to hide or to escape. Critical to the effort were false identity cards and he knew Assisi was quickly becoming a counterfeiting center. Dalla Costa asked for help procuring false papers for Jews in hiding. He would provide photographs, he told Niccacci, and would also arrange for the documents to be picked up by couriers.

It is reported that Dalla Costa personally recruited Bartali for the effort. He reached out to him through Emilio Berti, a pastry-shop owner who brought the cyclist to the cardinal. Dalla Costa was Bartali’s priest, spiritual guide, and close friend. And although he wasn’t the only courier in the underground, Bartali was uniquely placed as one of the few people in Italy with an excuse to travel long distances by bicycle; he would, indeed, ride forty thousand kilometers a year on his training routes. Now, he could save lives too.

Bartali would leave early in the morning, dressed in biking shorts and a jersey with his name emblazoned on the back. He did not need anyone to ride with him. An exceptional mechanic, he carried a screwdriver, wrench, and other tools, a little bit of cash, and a spare tire to handle any contingency. He would first ride from his home to the center of Florence to pick up the photographs and papers to be made into false identity cards. Sometimes he would get them from Berti. Other times they would come from a clergy member. Often Dalla Costa’s secretary, Monsignor Giacomo Meneghello, himself hid the cache under a pew at the cathedral.

Bartali would stash the documents under the seat of his bicycle or unscrew its frame, roll them up, and stuff them inside. Then he would head out on the 250-kilometer ride to Assisi. Incredibly, he would often return home the same day. His wife did not understand where he was going, but he assured her that he was just training. “He would leave the home almost daily to train,” she recalled later, and “sometimes he was away two or three days. I think he hid the truth about saving Jews to protect his family.” His admonition that she should tell anyone looking for him that he had an emergency or was going to get medicine for the baby did little to calm her fears. Bartali himself was given only limited information about the network of which he was now a part. He did not want to know the details of what the documents in his bicycle were, he recalled, “in case they catch me.”

Bartali would cycle on the often-damaged roads as far as Genoa and Rome. In Genoa, he would deliver forged documents, many used to help those fleeing for the United States and elsewhere, and pick up money that had arrived from Switzerland for the Curia in Florence. In Rome, he would see contacts in the Vatican. But Assisi was perhaps the most critical destination, where false documents were made and many Jews were in hiding.

Even in a religious town like Assisi, it would be very difficult for a celebrity like Bartali to go unrecognized, so riding by day, hiding in plain sight, was generally safer. At checkpoints he would be waved through or subjected to light chitchat about cycling. His legend had long ago made its way even into the cloisters behind the rose-colored stone buildings in Assisi. Pier Damiano, a twenty-year-old student of Niccacci’s at the monastery, remembered being stunned to see Bartali standing by a side door as he came out of his room one day, after which Damiano was sworn to secrecy by the father superior.

Bartali was frequently at the convent of San Quirico, where the mother superior, Giuseppina Biviglia, hid dozens of Jews in the guest- house and served as a conduit for false identification papers. He would ring the doorbell and head upstairs to drop off his parcels. Two nuns, Sisters Alfonsina and Eleonora, recalled Bartali coming dozens of times during the war. “He would arrive with his bicycle and would ask for the mother superior,” remembered Alfonsina. They would meet privately. “I can still see him. He was tall, strong, suntanned and had short pants.” Mother Giuseppina would record Bartali’s visits in her diary. An active member of the underground, she personally prevented the Nazis from breaking into her convent and made the dramatic decision to hide Jews, including men, in the cloister.

After meeting Giuseppina, sometimes Bartali would leave his bicycle at the convent and go to meet others in the center of Assisi. Other times he had barley coffee with Niccacci at the monastery, where he sometimes spent the night.

Having dropped off documents, Bartali would hide new batches of false identity papers made in a nearby printshop in the crossbar or handlebars of his bicycle. The counterfeiting ring in Assisi had quickly become a well-oiled machine. Sixty-eight-year-old Luigi Brizi owned a small stone-walled souvenir store on Via Santa Chiara, in a piazza opposite the Basilica di Santa Chiara, from which he also ran a foot-operated printing press. A lifelong atheist, he nonetheless played a friendly game of checkers at the Café Minerva each Wednesday with Niccacci, who one day appealed to him to make counterfeit papers for Jews in hiding or trying to escape. He struck a chord when he reminded Brizi, whose ancestors had been important local members of the Risorgimento, of the Jews’ contribution to the movement for Italian unification and independence, and of their patriotism.

Brizi agreed, but he did not want to involve his twenty-eight-year- old son, Trento, who had just returned safely from the Yugoslavian front. Several days later the young man asked his father what he was so intently working on. Brizi confessed but begged him not to get involved. “I fought for three years on the front,” Trento said. “I heard the bullets that were whistling around me and by now I am no longer afraid of anything. If you are doing something, I will do it too.” He was an expert at making the municipal rubber stamps necessary for each card. “While several of my friends climbed up into the mountains and became partisans,” Trento recalled, “I decided to stay at my print shop. My weapons against the Nazis were ink and paper.”

The first document was for a well-to-do Jewish engineering student from Trieste, Enrico Maionica, who became Enrico Martorana of Caserta, a city in the liberated zone. Maionica himself joined the effort, hiding with Niccacci’s help in a former laboratory in the cloisters of San Quirico, where he would finish the identity documents the Brizis printed by filling in information, forging signatures, and perfecting the art of applying fake seals. They created stamps for places like Sicily, Calabria, Lecce, Bari, Naples, Foggia, Taranto, and Caserta, all located behind Allied lines. Maionica procured ornate House of Savoy stamps, which he had seen on many old identification cards and which were available only to authorized printers. He also bought postage-stamp-size license tags for a few lire from Italians who no longer had cars and expertly transferred them onto the cards by soaking off the ink and regluing them. “I put three- or four-year-old tags to give them more authenticity,” he recalled. The documents would then be given to Father Niccacci or to Mother Giuseppina for Bartali to pick up, Maionica testified.

Eventually the Brizis were churning out hundreds of identity cards. “If the Nazis were to single out our print shop, we would be shot,” Trento real- ized. In early 1944 he was working on a batch of identity cards in the back of the shop and forgot to close the curtains when two German soldiers suddenly walked in. He froze with terror as one of them asked to buy images of Saint Clare for their wives. Relieved, Trento found two wooden carvings and refused payment, “a gift from Assisi to our German friends.”

Panicked, Trento rushed over to San Damiano to tell Padre Niccacci that he wanted out. “Instead, as soon as I arrived in the convent, something happened that made me forget the fear I had felt shortly before.” He was let in a side door by another monk and asked to wait in the courtyard. There, he caught sight of Niccacci talking with a young man, leaning on the handlebars of a magnificent bicycle and wearing short pants over muscular legs. “I saw him get on the seat of his bicycle and race off, from the main door, at a great speed.”

A stunned Trento asked if he had just seen Gino Bartali. Niccacci confessed that he had. He told him he must keep it a secret, and that Bartali had carried many of the Brizis’ documents to Perugia and Florence. “No one dares stop him,” he explained. Years later, Trento remembered the moment. “The idea of taking part in an organization that could boast of a champion like Gino Bartali among its ranks filled me with such pride that my fear took a back seat.”

Bartali also went on scouting missions for the underground and the partisans. On the road, he would make careful note of checkpoints and roadblocks and also relayed information from friends in the Resistance like Gennaro Cellai, the famous cobbler who made his custom biking shoes. It is also said that he served as the go-between with smugglers from Abruzzi, helping people cross the border into the Allied zone. He would be called upon by the partisans if they had an urgent warning that the OVRA (Opera Volontaria di Repressione Antifas- cista), Mussolini’s secret police, was about to arrest someone. “I was the only one,” he told his son, “that could move about at night with a certain degree of safety in Florence. My bike was in order. There were no loose screws. It was very quiet. I knew the city streets very well, I could cross it at a speed of 50 kilometers an hour. Just like in racing and despite the tram tracks, in just five minutes I could reach and give warning to anyone. Three or four times they shot at me at a checkpoint, but they never got me because I would arrive suddenly and silently and before they could realize what was happening, I was out of there.”

At least once Bartali stopped at Terontola, about halfway along the route from Florence to Assisi. The railway station at this small Tuscan town between Arezzo and Perugia was extremely busy, an intersection where Jews and dissidents on the run had to change trains. As elsewhere in Europe, train stations were the bane of a refugee’s existence, generally crawling with uniformed Fascist and German police who paced the platforms.

As part of a coordinated effort with local partisans, Bartali glided on his bicycle to the station. “My father would play the part of the great cycling champion,” his son explained. As soon as he walked in, news spread quickly throughout the town. While he greeted his friends. crowds began to form and press toward the superstar. As he signed autographs, he was offered a panini and cappuccino, and more and more people appeared. In response to the tumult, the patrolling officers approached to control the crowd (or perhaps get a glimpse themselves). While they were distracted, the partisans quickly moved the refugees from one train to another. “It was easier for the Jews to find an escape route in the midst of this artfully created bustle,” Andrea Bartali wrote. By the time the station had returned to normal and Bartali had ridden off, they were safely on their way.

By the spring of 1944, more than sixty-five hundred Jews had been deported, among them a thousand rounded up in one day in Rome, one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities, and another thousand in Florence, including fifty orphans.

One day Bartali received a summons to appear with Emilio Berti before Major Mario Carità of the secret police, who, along with two hundred underlings, assisted the Nazis in pursuing Jews and partisans. Bartali was terrified when he arrived at Carità’s headquarters in a repurposed luxury apartment building on Via Bolognese, nicknamed the Villa Triste because of the cries heard from inside. Carità, it was said, made a spectacle of torture, interrogating prisoners as he indulged in gluttonous feasts, drank wine, and had Neapolitan songs played on the piano.

Bartali was taken downstairs into the coal bunkers that served as prison cells, where an array of torture instruments were on display and the sounds of screaming echoed in the air. He noticed a pile of letters addressed to him that seemed to have been intercepted by the police, and was panicked as to what they could be. Eventually Carità confronted him. After an anti-Catholic tirade, he angrily read aloud a letter from the Vatican thanking Bartali for his help. In his free time, Bartali would gather food in the countryside for the poor and send it to the Vatican, but Carità accused him of sending them weapons.

Bartali denied it, telling him that he had sent flour, sugar, and coffee to needy people. He didn’t even know how to shoot, he told Carità, and always kept his pistol unloaded in the military.

Carità looked at him. “It’s not true,” he declared. Bartali insisted it was, and Carità threw him back into the dungeon to consider his position. Bartali remained there for some time, terrified. “These were times when life was not highly valued,” he remembered. “You could easily disappear as a result of hatred, a vendetta, rumor, slander, or ideological fanaticism.”

On the third day Carità once again called him for interrogation. Bartali again explained he had just gathered food and sent it to the Vatican. Carità still did not believe him.

It was at this point that one of Carità’s men stepped out of the shadows. It was Olesindo Salmi, Bartali’s former commanding officer, who had authorized his use of a bicycle instead of a motorcycle when he was in the army so he could stay in shape. “If Bartali says coffee, flour and sugar,” Salmi declared, “thenit was coffee, flour and sugar. He doesn’t lie.”

Bartali was stunned by the intervention, then further shocked as Carità backed off and released him. Carità told him they would meet again and ordered him to remain in Florence.

“I hope I never see you again,” Bartali mumbled.

“I think that was one of the few times that he was really scared,” his son wrote later. The Bartalis moved in with Berti in Via del Corso, in the heart of Florence near the Palazzo Vecchio, an area they believed less likely to be bombed and stayed there until Florence was liberated by the Allies.

Having been robbed of his prime racing years, Bartali went on to win the Tour de France again in 1948, one of the oldest men ever to do so. Several years later he retired to the quiet life of a former athlete but remained a major celebrity. Shortly after the war, rumors were already circulating among the Florentine Jewish community about Bartali’s involvement as a courier in the underground. In 1978 Alexander Ramati, a Polish soldier and reporter who had been present at the liberation of Assisi, published The Assisi Underground , which told the tale of the underground from the perspective of Father Niccacci and included the story of Gino Bartali. “I want to be remembered for my success in sport,” Bartali told his son, “not as a war hero. Others are war heroes, those who suffered in their limbs, their minds, and their hearts. I limited myself to doing what I knew how to do best. Riding a bicycle.”

One should do good but not talk about it, he believed. “These are things that are meant to be hidden,” Bartali once said of his wartime heroics. To discuss it would be to debase it, he believed, to benefit from others’ misfortunes. “I don’t want to talk about it or act like a hero,” he said once when asked about his wartime exploits during a broadcast.

In his later years, Bartali’s health began to fail. “Life is like a Giro d’Italia, which seems never-ending, but at a certain point you reach the final stage,” he told a reporter. “Yes, I’ll soon be called and I’ll go up there.” He was at peace. “Heaven should be a happy place, like those green summits of the Dolomite Mountains, after you’ve rounded a hundred curves, pedaling all the way.” On May 5, 2000, he passed away at home, surrounded by his family, at the age of eighty-five.

Bartali had confided his story to his son Andrea, who remembered his father wanting to return to Assisi to see the Giotto frescoes or to visit Nicolini at San Damiano. After repeated questioning, Bartali shared details about his work during the war with his son on long trips together in Italy, Germany, the United States, Canada, and elsewhere. But he told Andrea he could not tell anyone. “When the time comes to talk about these things, you will understand it by yourself,” he told him.

In 2004, when a young cyclist, Paolo Alberati, wrote his thesis on Bartali’s exploits, Andrea decided the time was right. In 2006 he published a book about his father. That year, on Liberation Day in April, the president of the Italian Republic awarded Bartali the Civilian Gold Medal for his actions. In 2013 Gino Bartali joined other members of the Assisi underground—including Niccacci and Dalla Costa—in being named as a Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem. In 2018, in a unique tribute, Bartali was made an honorary citizen of Israel, and the first three stages of the Giro d’Italia were held in the Holy Land, the first time they had ever been held outside Europe.

Precisely how many owed their lives to Gino Bartali will never be known, but it is likely several hundred. One he certainly saved was Giorgio Goldenberg, the little boy who hid in his cellar and who moved to Israel after the war and eventually became a grandfather. “Gino Bartali saved my life and saved the life of my family,” Goldenberg remembered. “He is a hero.” Bartali’s friend, the Vatican bookseller Bartolo Paschetta, had called Andrea down to Rome and told him on his deathbed, “You had a great father. You can’t know how many people he and we saved.” For Bartali, his heroics were something private and very much connected to his faith. “If you’re good at a sport, they attach the medals to your shirts and then they shine in some museum,” he told his son. But good deeds were of a different type, he believed. “These are medals that are pinned to the soul and will be recognized in the Heavenly Kingdom, not on this earth.”

Adapted from IN THE GARDEN OF THE RIGHTEOUS by Richard Hurowitz. Copyright © 2023 by Richard Hurowitz. Reprinted courtesy of Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

- Milano Cortina 2026

- Brisbane 2032

- Olympic Refuge Foundation

- Olympic Games

- Olympic Channel

- Let's Move

Gino Bartali, the two-time Tour de France winner with a secret life

Not until his death in 2000 did the role the Italian cyclist play in saving Jews during World War II – using his career as cover – come to light.

By the time road cyclist Gino Bartali got married on 14 November 1940, the Italian had won the Tour de France once and Giro D'Italia twice.

The wedding was celebrated by the Archbishop of Florence, Cardinal Dalla Costa, and the blessing performed by Pope Pius XII, such was the popularity of Bartali.

But it was for a very different reason that Bartali would come to be known as Ginettaccio in his home nation, and across the world as Gino le Pieux or Gino the Pious.

Using his cycling career as cover, Bartali helped save the lives of many Jewish people during World War II. Telling no one about his deeds, at his insistence, it was only after his death in 2000 at age 85, the story came to light.

Gino the Pious

Bartali was born in rural Tuscany in 1914, the hills around his home proving a happy cycling playground. Turning professional in his early '20s, his fame in Italy grew, soon anointed with a 'King of Cycling' moniker.

A devout Catholic, his strong moral convictions meant that on winning the 1938 Tour de France, Bartali did not dedicate the win to Italy's fascist leader, Benito Mussolini.

When war broke out in Europe in 1939, Bartali was conscripted into military service as a bike messenger, allowing him to continue training and racing.

In 1943, Elia Dalla Costa, who had been secretly aiding thousands of Jews seeking refuge, spoke with Bartali. A plan was hatched to use Bartali's fame and cover of lengthy training rides to cycle between cities across Italy, hiding falsified identity cards and other secret documents in the frame of his bike.

When stopped by checkpoint guards, Bartali asked them not to touch his bike; it is set up specifically to suit my racing style, he told them.

Bartali also hid a Jewish family in his apartment and then a nearby basement.

He was risking his life every time.

Liberation and triumph

Two years after Florence was liberated in August 1944, Bartali again won the Giro D'Italia , despite struggling to regain his physical and mental fitness after food shortages and the stresses of war.

In 1948, ten years after his first win, Bartali again claimed the Yellow Jersey at the Tour de France. A record for the longest period between wins – albeit through circumstance – that stands to this day.

It was during this Tour, against the background of Italy trying to regain some political stability, that the leader of the Italian Communist Party, Palmiro Togliatti, was severely injured after being shot in the neck by a sniper as he was leaving the parliament building. A revolt looming in his home nation, Bartali, who had been told the news, managed to win three stages of Le Tour, helping ease tensions with emotions distracted by joyful scenes.

Such was Bartali's sporting prowess, a song by Paolo Conte, released in 1979, is renowned throughout his home nation. The lyrics basically boil down to, you go to the cinema, I'm watching Gino Bartali race – the jaunty track has no reference to Bartali's war-time heroics, because no one knew about them.

And that was how Bartali liked it, telling his son Andrea Bartali:

"If you’re good at a sport, they attach the medals to your shirt and then they shine in some museum. That which is earned by doing good deeds is attached to the soul and shines elsewhere."

Related content

Tour de France 2023: Daily stage results and general classification standings

Tour de France 2023: Riders with most stage wins in Tour history - Complete list

From Biniam Girmay's brilliance to the BMX boom in South Africa: The story behind Africa's growth as a cycling continent

Masomah Ali Zada: Why I almost quit cycling in Afghanistan

You may like.

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

- Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- The Rwanda Genocide

Gino Bartali

Gino Bartali was one of the most beloved of Italian cyclists. He won the Tour de France in 1938 and 1948. His cycling achievements on the Alps and Pyrenees were legendary and earned him the nickname of “Giant of the Mountains.” Yet until recently, few knew that he risked his own life and his family's lives by helping to save hundreds of Jews during World War II.

With his cycling career as a cover, Bartali cycled perhaps thousands of kilometers between cities as far apart as Florence, Lucca, Genoa, Assisi, and the Vatican in Rome. Hidden in the frame of his bike were falsified identity cards and other secret documents.

His efforts helped save hundreds of Jews seeking refuge from other European countries.

In 2013, Yad Vashem recognized Gino Bartali as Righteous Among the Nations for his rescue activities.

- athletes and sports

Righteous Among the Nations

This content is available in the following languages.

Gino Bartali was born on July 18, 1914, in Ponte a Ema, a small village south of Florence, Italy. His father, Torello, was a day laborer. His mother helped support the family by working in the fields and embroidering lace. Gino had two older sisters, Anita and Natalina, and a younger brother, Giulio, who shared his passion for cycling and racing. Gino began to work at a young age, laboring on a farm and helping his mother with embroidery work.

At the age of 11, in order to attend middle school in Florence, Gino needed transportation. With his own earnings and with help from his father and sisters, he purchased his first bicycle. While riding the hilly roads of the region, Bartali started to develop and refine his racing skills. In 1931, at the age of 17, he won his first race.

Cycling Career

Bartali became a professional racer in 1935. He won his first Giro d'Italia the next year, in 1936. The Italian Cycling Federation then compelled him to compete in the Tour de France in order to increase Italy's cycling reputation abroad. Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini had risen to power in 1922 and had taken control of public and private institutions. Italian Fascists hoped that a victory in the Tour de France would demonstrate the superiority of the Fascism and the “Italian race.”

Bartali did, in fact, win the Tour de France in 1938. However, Bartali had no sympathies for the regime. He never dedicated his win to Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini, as tradition dictated. Consequently, he received no honors upon his return to Italy.

1938 also brought a dramatic change for Italian Jews as the Fascist Grand Council approved anti-Jewish measures based on Germany's Nuremberg Laws . These laws excluded Jews from most aspects of Italian life and would facilitate future deportations. They also marked the tightening of the alliance with Hitler's Germany.

On June 10, 1940, Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. In October, Bartali was called to active duty. Because of an irregular heartbeat, he was assigned to be an army messenger. Allowed to use his bicycle for his missions, Bartali was able to continue training and racing for the next three years.

Gino Bartali - Maps

During the German Occupation

The summer of 1943 was a pivotal moment for Italy. Mussolini was overthrown in July. In September, the new government signed an armistice with the Allies. Germany invaded the northern regions of the country, including Tuscany. With the German occupation, conditions for the Jewish population grew much worse.

Also in September 1943, Italian Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa asked to meet Bartali. Dalla Costa had been secretly aiding thousands of Jews seeking refuge from other European countries. The fugitives needed falsified identity cards. Dalla Costa shared his plan with Bartali. Under the cover of his long training rides, Bartali could carry counterfeit documents and photos in the hollow frame of his bike. The plan was a nearly perfect one as Bartali knew those roads well and his need to train provided an ideal alibi.

Despite the risks, Bartali accepted. For the following year, he rode while hiding the vital materials in the frame of his bicycle. Sometimes Bartali was accompanied by his training companions, who were unaware of his activities. When stopped at checkpoints, Bartali engaged the guards in conversation about cycling. He asked guards not to touch his bicycle, telling them that all the parts were adjusted in a special way to suit his racing style.

By coincidence, shortly after he started his underground activity, Bartali was asked to hide a Jewish family whom he knew well. Giorgio Goldenberg, his wife, and their son hid in Bartali's cellar until Florence was liberated.

As the war progressed and cycling races were cancelled, Bartali's cover began to appear less credible. In July 1944, Bartali was interrogated at Villa Triste (Sorrow House) in Florence, where local Fascist officials imprisoned and tortured their prisoners. Fortunately, one of Bartali's interrogators happened to be his one-time army commander, who convinced the other interrogators that Bartali was innocent of any charges.

Liberation and After

Florence was liberated on August 11, 1944. Drained by the events of the war and by his underground activities, Bartali had to struggle to regain his mastery of cycling. He went on to win the Giro d'Italia in 1946. With a stunning performance in the mountains of France, he won the 1948 Tour de France (10 years after his first Tour de France victory).

Righteous among the Nations

For many years after the war, Bartali did not speak about his role in saving hundreds of people, sharing just a few details with his son Andrea. It was only after his death that Bartali's rescue activities came to light. In 2013, Yad Vashem recognized Gino Bartali with the honor of Righteous Among the Nations .

Series: Righteous Among the Nations

Martha and Waitstill Sharp

Jan zwartendijk.

Father Jacques

Oskar Schindler

Le Chambon-sur-Lignon

Corrie ten Boom

Chiune Sugihara

Raoul Wallenberg and the Rescue of Jews in Budapest

Mohamed Helmy

Critical thinking questions.

- What pressures and motivations may have influenced Bartali's decisions and actions?

- Are these factors unique to this history or universal?

- How can societies, communities, and individuals reinforce and strengthen the willingness to stand up for others?

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Remembering the Tour de France riders who died in the first world war

The Tour de France lost great champions, characters and cyclists to the war that swept through Europe in 1914. They will be honoured this summer during the first world war centennial

Do you remember that hour of din before the attack And the anger, the blind compassion that seized and shook you then As you peered at the doomed and haggard faces of your men? Do you remember the stretcher cases lurching back With dying eyes and lolling heads – those ashen-grey Masks of the lads who once were keen and kind and gay? Have you forgotten yet?... Look up, and swear by the green of the spring that you’ll never forget.

- Aftermath, by Siegfried Sassoon (1919)

Every French town and village has one – from the simple soldier leaning on his rifle to overblown celebrations of mass slaughter. And each one of the estimated 30,000 war memorials that pepper the French landscape lists the names of the sons and brothers, fathers and uncles who travelled to the great slaughterhouses of the Western Front and lie forever under the mud of the Somme and Ypres, Verdun and the Marne. Their sacrifice marked forever by those simple words " Mort Pour La France".

On 9 July 2014 the Tour de France will leave the shadow of the Menin Gate in Ypres, where the Last Post still sounds at sunset, and wend its way over nine sections of cobbles shadowing the route of the "Hell of the North", Paris-Roubaix, before threading its way east and into the once disputed territories of Alsace and Lorraine. Passing the Menin Gate, Arras, the Chemin des Dames , Verdun and Douaumont, the 2014 Tour will pay its respects to the fallen of the first world war – and in doing so it will remember the riders of the Tour de France who died in the "war to end all Wars".

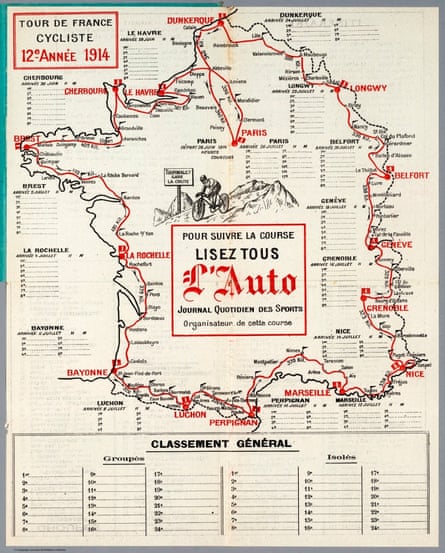

The 1914 Tour should be remembered for Philippe Thys’s second victory (and he would go on to win a third in 1920), but Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Gavrilo Princip on the 28 June as Thys was stamping his authority on the race by winning the first stage – from Paris to Le Havre – and the events that unleashed the hell of the first world war escalated rapidly throughout the month of July. Six days after the Tour finished, France ordered military mobilisation and, by 3 August, France and Germany were at war.

Despite Desgrange’s desire to run the race in 1915, the Tour was suspended until 1919, when it would return to the battle-scarred roads of France with stages to Strasbourg "le jour de gloire" and Metz "the day of memory". And there would be a new symbol of renewal and rebirth: Le Maillot Jaune . Imagine how the Yellow Jersey must have blazed and glowed as the Tour entered those devastated territories of eastern France.

The Belgians would go on to dominate the postwar years but the reason for their domination may have more to do with the way the guerre mondiale played out than any supposed physical superiority on behalf of the Belgians. While the French lost 1,397,800 young men in combat, the Belgians lost just 58,637.

Belgium was neutral in 1914 and, though her tiny army chose to fight – and created a breathing space for the British and French forces to organise their campaigns in doing so – the country was swiftly occupied. While the French lost a generation of champions on the battlefield, the Belgians endured the German occupation – the "Rape of Belgium".

It hardened attitudes and crystallised a resistance around the idea of Flemish nationalism. And so began the rise of the Flahutes , the hardmen, who were older, tougher and wiser, inured to hardship and with a point to prove. The average age of a Tour de France winner rose sharply from 1919 and didn’t begin to fall again until 1930, when a 26-year-old called André Leducq triumphed for France.

There was one other huge impact on the race. With trade teams unable to individually organise the equipment they needed for their riders to mount an assault on the Tour – so much had been sequestered for the war effort and the market for new bicycles was slim – they were forced to co-operate and ride for the conglomerate La Sportive team in uniform grey jerseys, their team allegiances denoted only by different coloured epaulettes: purple for Peugeot, dark green for Automoto, blue for Alcyon and so on.

It is almost impossible now to imagine the 1914 Tour continuing against the backdrop of the escalating political crisis. During his 200km solo breakaway on stage 13, Francois Faber was followed for part of the way by an armed soldier from one of the French bicyclist battalions yet in the images of the time he rides on oblivious. Desgrange, editorialising in l’Auto on 3 August 1914, was typically bullish:

“It’s a big match that you have to fight: make good use of all your repertoire. Tactics should hold no worries for you. Use your guile and you’ll return…you know all that, my lads, better than me who you’ve been teaching for nearly 15 years. But be careful! When your rifle is pointed at their chest, they’ll ask your forgiveness. Don’t give it to them. Crush them without pity.”

Desgrange stood behind his words and volunteered for the French army as a poilou and served with the infantry, though he was in his fifties by then. He would win the Croix de Guerre for his efforts and continue to write for l’Auto throughout the war. Already his thoughts were turning towards the next Tour de France.

Many of the riders who had competed in the first 11 years of the race would not live to see the 1919 Tour, including three of the great pre-war Tour champions who never returned from the battlefield.

Francois Faber (who won the Tour in 1909 to become the first foreign champion) was killed Mont-Saint-Eloi on 9 May 1915. The Luxembourgeois was fighting in the First Regiment of the Foreign Legion. His body was never found. A monument to him exists in Albain-Saint-Nazaire. He was the "Geant de Colombes" who won six stages, including an unbeaten record five in a row in the 1909 Tour de France to seal the victory and take his place in the history books.

The word panache might have been coined for Faber's exploits in that race; he took one stage with a 255km solo escape to finish 33 minutes ahead of his rivals; he won another by passing over the Ballon d’Alsace, then he raced along the cols Porte, Laffrey and Bayard in first place while the heavens threw all they could muster at him. He was hoisted shoulder high by the crowds in Paris when he sprinted across the final line in the Parc des Princes , his bike on his back, having broken his chain 3km from the finish. Of such stuff was the Geant de Colombes made.

Octave Lapize, who won the Tour in 1910, was shot down on Bastille Day in 1917. Lapize – nicknamed Le Frise for his mop of curls – won the first historic raid through the Pyrenees in 1910 and encapsulated all his anger and frustration in that one word "Assassins!" Lapize was the first rider ever to cross the summit of the Tourmalet – his steel statue , le Geant , is towed to the summit on the first Saturday of June every year. You can ride up alongside him as he makes his way to the top of the climb, into the rarefied air at 2,122m.