kaurnaculture

Kaurna culture language mythology, tjilbruke dreaming tracks.

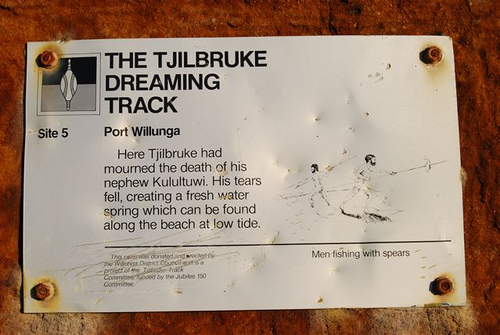

Tjilbruke is pivotal to the creation theories of the Kaurna people . He is an important Creation Ancestor in the lore of the Adelaide Plains . His tale tells of a time when peaceful laws governed the land and people. Tjilbruke lived as a mortal man and was one to whom the law was entrusted. Tjilbruke’s nephew, Kulutuwi was killed as punishment for breaking the law by killing a female emu. Tjilbruke then carried his nephews body down the Fleurieu Peninsula coast into Ngarrindjeri country near Goolwa. Where Tjilbruke rested on his journey, his luki (tears) of overwhelming grief formed the freshwater springs at Kareildung ( Hallett Cove ), Tainbarang ( Port Noarlunga ), Potartang (Red Ochre Cove), Ruwarunga ( Port Willunga ), Witawali ( Sellicks Beach ), and Kongaratinga (near Wirrina Cove); this trail is known as the Tjilbruke Dreaming Tracks. Eventually Tjilbruke placed the body of his nephew into a cave at Rapid Bay and transformed himself into the glossy ibis bird, known in the Kaurna language as Tjilbruke .

Since colonization an effort has been made to preserve the Tjilbruke Dreaming Tracks but because of the nature of the modern landscape the trail is spread over public and privately owned land. This has made it difficult to maintain certain sections of the trail. Monuments to both Tjilbruke and Kulutuwi as well as commemoration plaques have been erected along the trail which have become tourist attractions in themselves.

Most parts of the trail are easily accessible to the public with markers signifying significant Indigenous sites beginning at Hallett Cove and stretching down the south coast as far as Rapid Bay.

“For a number of Aboriginal people the Sellicks Beach sites (together with the other marked locations on the Tjirbruke [sic] Track) are a symbol of the past as a place of origin. This past, which can be re-created by history and archaeology, has become the means by which people orient themselves towards the future.”

Rod Lucas, Lecturer, Honours Coordinator University of Adelaide Department of Anthropology .

Watch this short video to learn more about the history of the Tjilbruke Springs and the Kaurna nation : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fSQ6AkPjbz4 .

Related articles

- Snorkelling on the South Australian Coast (southaustraliansnorkeling.wordpress.com)

- 28 Councils Negotiating an Indigenous Land Use Agreement with the Kaurna (mayorclyne.com)

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Español NEW

Tjilbruke facts for kids

Tjilbruke (also Tjirbruki , Tjilbruki , Tjirbruke , Tjirbuk or Tjirbuki ,) is an important creation ancestor for the Kaurna of the Adelaide plains in the Australian state of South Australia . Tjilbruke was a Kaurna man, who appeared in Kaurna Dreaming dating back about 11,000 years. The Tjilbruke Dreaming Track or Tjilbruke Dreaming Trail is a major Dreaming trail , which connects sites from within metropolitan Adelaide southwards as far as Cape Jervis , some of which are Aboriginal sacred sites of great significance.

Man and creator-being

Variant spellings and versions, tjilbruke dreaming story, creation of the tjilbruke dreaming track (1986–2006), the tjilbruki gateway (1997), warriparinga (2001), other public commemorations of tjilbruke.

The Tjilbruke Dreaming pre-dates European contact , probably arising when the "Adelaide plains tribe", the Kaurna, settled the area at least 2,000 years BP (as evidenced by archaeological finds at Hallett Cove , where Kaurna campsites succeeded those of the Kartan people of Kangaroo Island , who had been there tens of thousands of years earlier). Kaurna Yerta Parngkarra (Kaurna tribal country) stretches from Cape Jervis in the south, to Crystal Brook in the north, west to the Mount Lofty Ranges , across to Gulf Saint Vincent, including the plains and city of Adelaide.

The Tjilbruke story became part of the southern Kaurna Dreaming . It is more than a creation story ; it assumes the status of a religion for some, sets standards and rules for living, and provides spiritual meaning. It is both lore and law . The lore tells of a time when all their lived in accord with peaceful trading laws which governed all their lives. The law was brought to the land, and "Old Tjirbruki", who lived as an ordinary man, a keeper of the law which came from the south, after the water covered the land (when Wongga Yerlo , or Gulf St Vincent, was created.). Tjilbruke was renowned as a "great hunter and firemaker", and a hero of the Kaurna. He also played a role in helping to protect the animals and the territory of the Kaurna, while at the same time having respect towards neighbouring peoples. It was part of his and Kaurna way of life to value all life, whether animal or human.

In about 1840, anthropologist Ronald Berndt recorded the spellings "Tjirbuk" or "Tjirbuki" from Ngarrindjeri man Albert Karlowan, as the name of a small wetland . Anthropologist Norman Tindale of the South Australian Museum recorded the spelling as Tjirbruki, but Tjilbruke is the commonly used spelling today.

Since the early 1980s the Williams family, of the Mullawirra and Mulla mai/Kudnarto clans , have been senior custodians of the Tjilbruke story, and Karl Winda Telfer has collaborated with Gavin Malone to share the story. Milerum, also known as Clarence Long, has also been a contributor. The Tjilbruke story is part of a bigger and more complex story known as the Munaintya Dreaming, that has been passed down through oral tradition through the years.

The tale of Tjilbruke's journey down the east coast of Wongga Erlo/Gulf St Vincent is the best known of all Kaurna Dreaming stories, and has become a symbol of renewal of the Kaurna culture, although it was first recorded from Ngarrindjeri sources by Tindale and later Ronald and Catherine Berndt . It was recorded by Tindale over a period of many years up to 1964, but it was not until 1987 that he published the most complete version hitherto published, as The Wanderings of Tjirbruki: a tale of the Kaurna People of Adelaide .

The story starts with an emu ( kari ) hunt by three one men, Kulultuwi, Jurawi and Tetjawi. They were all nephews of Tjilbruke, but Kulultuwi had a special relationship to his uncle, as he was the son of his sister, and known as his nangari ; the other two were his half-brothers. Tjilbruke was responsible for Kulutwi, as an uncle as well as a father, to help him grow up correctly and do the right thing. While the young men went hunting in the Tarndanya (Adelaide) area, across Mikkawomma (the plains) to Yerta Bulti ( Port River estuary ), driving the birds up Mudlangga (Le Fevre Peninsula), Tjilrbuke went fishing at Witu-wattingga (the Brighton area). After finishing his fishing, he set up camp at Tulukudangga/Tulukudank (Kingston Park and then started tracking an emu southwards. When Kulultuwi returned to the area, he found himself tracking the same emu as his uncle, which he was forbidden to do. However he killed the emu, and Tjilbruke, although initially angry, forgave him when he gave him some of the emu meat. (In one version of the story, although Kulultuwi was not supposed to have killed the kari ahead of his uncle, Tjilbruke gave him permission to do so, as long as he gave him some of the meat.)

While Kulultuwi was cooking the emu meat over a fire, Jurawi and Tetjawi killed him with their spears, as punishment for his breaking the law of the clan. The brothers took the body to their clan campsite at Warriparri (Sturt River) and told them the story, and they started to dry the body with smoke, as custom dictated. After Tjilbruke found out, he was very upset, and speared the two nephews to death (in retaliation, applying the law, being a man of the law), before carrying Kulultuwi's body to Tulukudangga, where an inquest and ceremony to complete the smoking of the body was held.

The story goes on to tell of how six freshwater springs were created by Tjilbruke's tears, as he carried the body of his dead nephew from Warriparri across to the coast and southwards past Aldinga Beach and onto the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula to Rapid Bay . The Dreaming includes locations in several geographic areas: the Adelaide Plains , the Fleurieu Peninsula, on the south coast at Rosetta Head (The Bluff) near Victor Harbour , and also in the Adelaide Hills at Brukunga ; so it takes in Ramindjeri and Peramangk country.

After Kulultuwi's body had been smoked and dried, Tjilbruke picked up the body and carried it firstly to Tulukudangga/Tulukudank. Here some versions of the story diverge slightly; one says that he wept at this point and his tears created this spring, while another says that Tulukudangga was an existing spring at that place. From Tulukudangga, Tjilbruke carried Kulultuwi's body all the way down the eastern side of Gulf St Vincent and onto and down the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula. At sunset every night of his journey Tjilbruke cried over his nephew's body, and his tears transformed into freshwater springs at six locations:

- Kareildung (Hallett Cove)

- Tainbarang (Port Noarlunga)

- Potartang (Red Ochre Cove, near Moana Beach )

- Ruwarunga (Port Willunga)

- Witawali (Sellicks Beach)

- Kongaratinga (near Wirrina Cove, or Yankalilla )

He arrived at a cave ( perki ) at Rapid Bay , near Cape Jervis, and then emerged from underground at Wateira nengal (Mount Hayfield) and created yellow ochre . He walked on to Lonkowar (The Bluff/Rosetta Head, in Ramindjeri country), near Victor Harbor, where he killed a grey currawong , rubbed its fat onto his body and tied its feathers onto his arms, before transforming himself into a glossy ibis (or other wading bird ; in some sources, a blue crane ) as his spirit left his body. His body became the pyrite outcrop at Brukunga.

Saddened by these events Tjilbruke decided he no longer wished to live as a man. His spirit became a bird, the Tjilbruke ( Glossy Ibis ), and his body became a martowalan (memorial) in the form of the baruke ( iron pyrites ) outcrop at Barrukungga, the place of hidden fire ( Brukunga - north of Nairne in the Adelaide Hills). Tjilbruke was a master at fire-making.

The Tjilbruke Monuments Committee was formed by Robert Edwards of the South Australian Museum (SAM), sculptor John Dowie and staff of the Sunday Mail in 1971. It was largely due to the efforts of Edwards and other non-Aboriginal people that drove the early promotion of Kaurna cultural tourism. A public appeal helped to fund the marking of the trail by plaques and sculptures, to pay homage to the Kaurna culture and to attract and educate tourists. In 1972 John Dowie created the sculpture known as the Tjilbruke Monument at Kingston Park, within the City of Holdfast Bay .

Cairns were created at significant points along the Tjilbruke Trail articles and booklets were published in the 1980s, and the trail was included in Aboriginal Studies curricula. However, there was little input from Kaurna at this stage.

In 1981, Georgina Williams (SAM) began to research the trail. It was important to her "because Tjilbruke was to me an example of the law of my people and of the law related to the land and the places along the coast". A number of the sites have special spiritual significance, and in the 1980s, work by the successor to the Tjilbruke Monuments Committee, the Tjilbruke Track Committee, on the track became a central focus of Kaurna identity. The Committee was later renamed the Kaurna Heritage Committee and then grew into the Kaurna Aboriginal Community and Heritage Association (KACHA) in the 1990s, which became recognised as the representative body for all Kaurna on cultural heritage and other matters.

The Tjilbruke Dreaming Track, or Tjilbruke Dreaming Trail, marked by commemorative plaques at ten locations, was created during the 150th anniversary of British colonisation of South Australia (1986), along the coast in close proximity to the sea shore. Various events, mostly celebrating white history, were held throughout the year, with the final celebrations on December 28, 1986, 150th anniversary of the Proclamation of South Australia . However the Dreaming Track was one of about 30 Aboriginal projects which were considered, and was a major undertaking. While the original idea had been to erect a monument at Rosetta Head/The Bluff at Victor Harbor, the site where Tjilbruke’s spirit left earth and turned into the ibis, Georgina Williams pushed for the idea of the track, with several sites down the coast marked, "to provide a contemporary Kaurna presence within the physical public space of their own lands and in the public imagination".

In 2005, the City of Marion partnered with the City of Holdfast Bay , City of Onkaparinga and Yankalilla District Council to develop the Kaurna Tappa Iri Regional Agreement 2005-2008 (Walking Together) , in which the Tjilbruki Dreaming Trail featured significantly. In 2006, six Kaurna interpretive signs were installed along the trail, in a collaboration with the state government . The markers have immense cultural and social significance for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and help to bring Aboriginal cultural meaning to a wider audience.

Heading south from the Tjilbruke Monument at Kingston Park, there are ten markers, located at the following places:

- 1 Hallett Cove/Karildilla, at a reserve on Weerab Drive

- 2 Hallett Cove Karildilla, on Heron Way at the foreshore – site of the first spring

- 3 Port Noarlunga/Tainbarilla – at Tutu Wirra Reserve – site of the second spring

- 4 Red Ochre Cove/Karkungga – site of the third spring

- 5 Port Willunga/Wirruwarrungga, Esplanade – site of the fourth spring

- 6 Sellicks Beach/Witawodli, Esplanade/Francis Street – site of the fifth spring

- 7 Carrickalinga Head/Karragarlangga, foreshore

- 8 Wirrina Cove Resort/Kongaratinga, entrance forecourt – site of the sixth spring

- 9 Rapid Bay/Patpangga, foreshore

- 10 Cape Jervis/Parawerangk, lookout car park

In 2009, a walkway was created to provide better access to Tulukudangga Spring at Kingston Park, with new interpretative signage.

In the current City of Marion Reconciliation Plan, it is planned to "Collaborate with neighbouring Councils to promote the local Kaurna Tjilbruke Dreaming Tracks" in June 2022.

The Tjilbruki Gateway is a modern art installation installed by the City of Marion at Warriparinga ("windy place by the river"), developed by Adelaide artists Margaret Worth , Sherry Rankine and Gavin Malone. A complex and highly symbolic artwork, it incorporates coloured sands from the Red Ochre Cove area, morthi ( tinder ) made from Stringybark tree trunks, and eucalypts . After being planned since 1995, official opening in October 1997 was attended by the Governor General of Australia , William Deane , Lowitja O'Donoghue , and several Kaurna representatives, and celebrated with traditional ceremony and dance.

A federal government -funded reconciliation project in partnership with the City of Marion and the Kaurna community (Dixon and Williams clans) worked together to create a visitor and education centre for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to come together and reconcile their differences in the now metropolitan suburb of Marion, South Australia at a site known as site at Warriparinga. This site at Bedford Park within the grounds of Warriparinga wetland and Sturt River , a traditional ceremonial camp site for Kaurna. Opened in 2001, it was named the Warriparinga Interpretive Centre, subsequently becoming the Living Kaurna Cultural Centre .

The Tjilbruke Dreaming is referred to in eleven sites around Adelaide city centre. The first might be the ibis and Aboriginal man represented in the Three Rivers Fountain , sculpted by John Dowie and first unveiled in 1963 in Victoria Square/Tarndanyangga.

There is a plaque at Mt Lofty Summit with information about Tjilbruke.

Designed by Kokatha artist Darryl Pfitzner "Mo" Milika, the outdoor art installation Yerrakartarta , meaning "at random" or "without design", was created with the assistance of several other artists including Kaurna/Ngarrindjeri artist Muriel van der Byl AM , ceramicists Jo Fraser, Stephen Bowers, and Jo Crawford from 1993 to 1994 on the forecourt of the Hyatt, now Intercontinental Hotel, on North Terrace in Adelaide. It was at the time "the largest Australian commission for an Aboriginal public artwork", and represents the history of the land through the forms of animals forms cut into the pavement, and, on the wall surrounding the area, a huge ceramic mural depicting the Tjillbruke Dreaming story.

Other commemorations include:

- 1990s: Tjilbruke Dreaming Mural, Brompton Primary School

- 1997: Cultural Path Signal Box Park, Rosewater

- 1998: Tjilbruke Dreaming Mural, O'Sullivan Beach Primary School

- 2006: Warriparinga Walk Mural, under the Southern Expressway bridge at Warriparinga, Bedford Park

- 2002: Kaurna meyunna, Kaurna yerta tampendi – "Recognising Kaurna people and Kaurna land", Adelaide Festival Centre , with a carved stone to represent the springs

- 2007: Towilla Yerta Reserve, Port Willunga – pavement pattern includes a tear shape, and there is interpretive signage referring to the Dreaming

- 2009: Glow / Taltaityai , Walter Morris Drive, Port Adelaide , with representations of ibis and emus

- This page was last modified on 16 October 2023, at 16:53. Suggest an edit .

Tjilbruke (also Tjirbruki , Tjilbruki , Tjirbruke , Tjirbuk or Tjirbuki ,) is an important creation ancestor for the Kaurna people of the Adelaide plains in the Australian state of South Australia . [1] Tjilbruke was a Kaurna man, who appeared in Kaurna Dreaming dating back about 11,000 years. [2] The Tjilbruke Dreaming Track or Tjilbruke Dreaming Trail is a major Dreaming trail , which connects sites from within metropolitan Adelaide southwards as far as Cape Jervis , some of which are Aboriginal sacred sites of great significance. [3]

Man and creator-being

Variant spellings and versions, tjilbruke dreaming story, creation of the tjilbruke dreaming track (1986–2006), the tjilbruki gateway (1997), warriparinga (2001), other public commemorations of tjilbruke, external links.

The Tjilbruke Dreaming pre-dates European contact , probably arising when the "Adelaide plains tribe", the Kaurna, settled the area at least 2,000 years BP (as evidenced by archaeological finds at Hallett Cove , where Kaurna campsites succeeded those of the Kartan people of Kangaroo Island , who had been there tens of thousands of years earlier). [2] Kaurna Yerta Parngkarra (Kaurna tribal country) stretches from Cape Jervis in the south, to Crystal Brook in the north, west to the Mount Lofty Ranges , across to Gulf Saint Vincent, including the plains and city of Adelaide. [4] [5]

The Tjilbruke story became part of the southern Kaurna Dreaming . [2] It is more than a creation story ; it assumes the status of a religion for some, sets standards and rules for living, and provides spiritual meaning. It is both lore and law . [3] The lore tells of a time when all the people lived in accord with peaceful trading laws which governed all their lives. The law was brought to the land, and "Old Tjirbruki", who lived as an ordinary man, a keeper of the law which came from the south, after the water covered the land (when Wongga Yerlo , or Gulf St Vincent, was created. [4] ). Tjilbruke was renowned as a "great hunter and firemaker", and a hero of the Kaurna. He also played a role in helping to protect the animals and the territory of the Kaurna, while at the same time having respect towards neighbouring peoples. It was part of his and Kaurna way of life to value all life, whether animal or human. [6]

In about 1840, anthropologist Ronald Berndt recorded the spellings "Tjirbuk" or "Tjirbuki" from Ngarrindjeri man Albert Karlowan, as the name of a small wetland . [7] Anthropologist Norman Tindale of the South Australian Museum recorded the spelling as Tjirbruki, but Tjilbruke is the commonly used spelling today. [4]

Since the early 1980s the Williams family, of the Mullawirra and Mulla mai/Kudnarto clans , have been senior custodians of the Tjilbruke story, and Karl Winda Telfer has collaborated with Gavin Malone to share the story. Milerum, also known as Clarence Long, has also been a contributor. The Tjilbruke story is part of a bigger and more complex story known as the Munaintya Dreaming, that has been passed down through oral tradition through the years. [4]

The tale of Tjilbruke's journey down the east coast of Wongga Erlo/Gulf St Vincent is the best known of all Kaurna Dreaming stories, and has become a symbol of renewal of the Kaurna culture, although it was first recorded from Ngarrindjeri sources by Tindale and later Ronald and Catherine Berndt . It was recorded by Tindale over a period of many years up to 1964, but it was not until 1987 that he published the most complete version hitherto published, as The Wanderings of Tjirbruki: a tale of the Kaurna People of Adelaide . [8]

The story starts with an emu ( kari ) hunt by three men, Kulultuwi, Jurawi and Tetjawi. They were all nephews of Tjilbruke, but Kulultuwi had a special relationship to his uncle, as he was the son of his sister, and known as his nangari ; the other two were his half-brothers. [4] Tjilbruke was responsible for Kulutwi, as an uncle as well as a father, to help him grow up correctly and do the right thing. [6] While the young men went hunting in the Tarndanya (Adelaide) area, across Mikkawomma (the plains) to Yerta Bulti ( Port River estuary ), driving the birds up Mudlangga (Le Fevre Peninsula), Tjilrbuke went fishing at Witu-wattingga (the Brighton area). After finishing his fishing, he set up camp at Tulukudangga /Tulukudank ( Kingston Park and then started tracking an emu southwards. When Kulultuwi returned to the area, he found himself tracking the same emu as his uncle, which he was forbidden to do. However he killed the emu, and Tjilbruke, although initially angry, forgave him when he gave him some of the emu meat. [4] (In one version of the story, although Kulultuwi was not supposed to have killed the kari ahead of his uncle, Tjilbruke gave him permission to do so, as long as he gave him some of the meat. [9] )

While Kulultuwi was cooking the emu meat over a fire, Jurawi and Tetjawi killed him with their spears, as punishment for his breaking the law of the clan. The brothers took the body to their clan campsite at Warriparri (Sturt River) and told them the story, and they started to dry the body with smoke, as custom dictated. After Tjilbruke found out, he was very upset, and speared the two nephews to death (in retaliation, applying the law, being a man of the law [9] ), before carrying Kulultuwi's body to Tulukudangga, where an inquest and ceremony to complete the smoking of the body was held. [4]

The story goes on to tell of how six freshwater springs were created by Tjilbruke's tears, as he carried the body of his dead nephew from Warriparri across to the coast and southwards past Aldinga Beach and onto the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula to Rapid Bay . [8] [6] The Dreaming includes locations in several geographic areas: the Adelaide Plains , the Fleurieu Peninsula, on the south coast at Rosetta Head (The Bluff) near Victor Harbour , and also in the Adelaide Hills at Brukunga ; so it takes in Ramindjeri and Peramangk country. [8]

After Kulultuwi's body had been smoked and dried, [9] Tjilbruke picked up the body and carried it firstly to Tulukudangga/Tulukudank. Here some versions of the story diverge slightly; one says that he wept at this point and his tears created this spring, [6] while another says that Tulukudangga was an existing spring at that place. [8] From Tulukudangga, Tjilbruke carried Kulultuwi's body all the way down the eastern side of Gulf St Vincent and onto and down the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula. [6] At sunset every night of his journey Tjilbruke cried over his nephew's body, and his tears transformed into freshwater springs at six locations: [1]

- Kareildung (Hallett Cove)

- Tainbarang (Port Noarlunga)

- Potartang (Red Ochre Cove, near Moana Beach )

- Ruwarunga (Port Willunga)

- Witawali (Sellicks Beach)

- Kongaratinga (near Wirrina Cove, or Yankalilla [6] )

He arrived at a cave ( perki [9] ) at Rapid Bay , near Cape Jervis, [6] and then emerged from underground at Wateira nengal ( Mount Hayfield ) and created yellow ochre . He walked on to Lonkowar (The Bluff/Rosetta Head, in Ramindjeri country [4] ), near Victor Harbor, [8] where he killed a grey currawong , rubbed its fat onto his body and tied its feathers onto his arms, [4] before transforming himself into a glossy ibis (or other wading bird ; [6] in some sources, a blue crane [3] ) as his spirit left his body. His body became the pyrite outcrop at Brukunga. [8]

Saddened by these events Tjilbruke decided he no longer wished to live as a man. His spirit became a bird, the Tjilbruke ( Glossy Ibis ), and his body became a martowalan (memorial) in the form of the baruke ( iron pyrites ) outcrop at Barrukungga, the place of hidden fire ( Brukunga - north of Nairne in the Adelaide Hills). Tjilbruke was a master at fire-making . [8] [9]

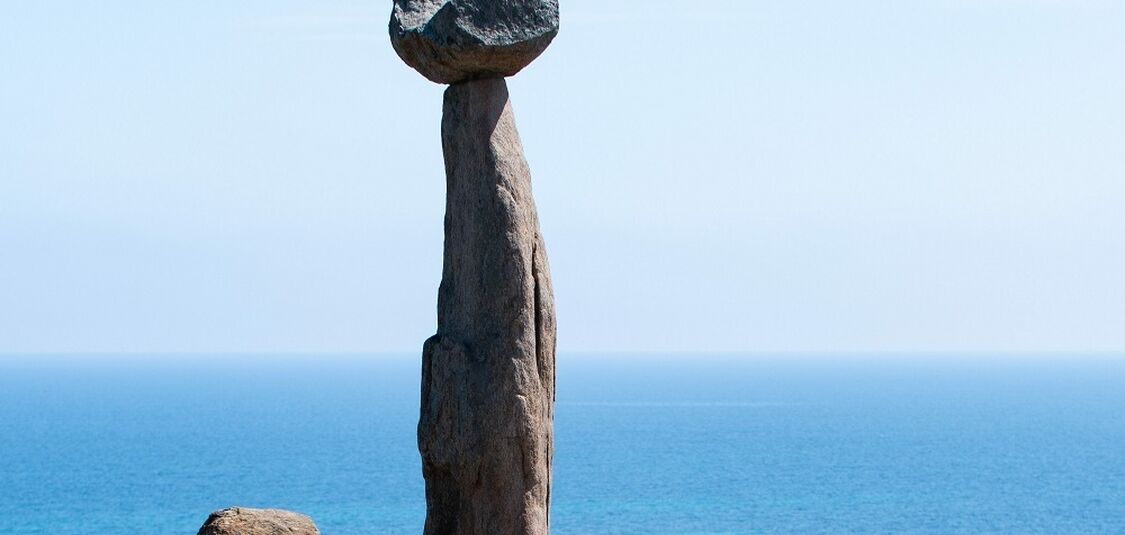

The Tjilbruke Monuments Committee was formed by Robert Edwards of the South Australian Museum (SAM), sculptor John Dowie and staff of the Sunday Mail in 1971. It was largely due to the efforts of Edwards and other non-Aboriginal people that drove the early promotion of Kaurna cultural tourism . A public appeal helped to fund the marking of the trail by plaques and sculptures, to pay homage to the Kaurna culture and to attract and educate tourists. In 1972 John Dowie created the sculpture known as the Tjilbruke Monument at Kingston Park , within the City of Holdfast Bay . [3] [8]

Cairns were created at significant points along the Tjilbruke Trail articles and booklets were published in the 1980s, and the trail was included in Aboriginal Studies curricula. However, there was little input from Kaurna people at this stage. [3]

In 1981, Georgina Williams [Note 1] (SAM) began to research the trail. It was important to her "because Tjilbruke was to me an example of the law of my people and of the law related to the land and the places along the coast". A number of the sites have special spiritual significance, and in the 1980s, work by the successor to the Tjilbruke Monuments Committee, the Tjilbruke Track Committee, on the track became a central focus of Kaurna identity. The Committee was later renamed the Kaurna Heritage Committee and then grew into the Kaurna Aboriginal Community and Heritage Association (KACHA) in the 1990s, which became recognised as the representative body for all Kaurna people on cultural heritage and other matters. [3]

The Tjilbruke Dreaming Track, or Tjilbruke Dreaming Trail, marked by commemorative plaques at ten locations, was created during the 150th anniversary of British colonisation of South Australia (1986), along the coast in close proximity to the sea shore. Various events, mostly celebrating white history, were held throughout the year, with the final celebrations on December 28, 1986, 150th anniversary of the Proclamation of South Australia . However the Dreaming Track was one of about 30 Aboriginal projects which were considered, and was a major undertaking. While the original idea had been to erect a monument at Rosetta Head/The Bluff at Victor Harbor, the site where Tjilbruke’s spirit left earth and turned into the ibis, Georgina Williams pushed for the idea of the track, with several sites down the coast marked, "to provide a contemporary Kaurna presence within the physical public space of their own lands and in the public imagination". [8]

In 2005, the City of Marion partnered with the City of Holdfast Bay , City of Onkaparinga and Yankalilla District Council to develop the Kaurna Tappa Iri Regional Agreement 2005-2008 (Walking Together) , in which the Tjilbruki Dreaming Trail featured significantly. In 2006, six Kaurna interpretive signs were installed along the trail, in a collaboration with the state government . [10] The markers have immense cultural and social significance for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, and help to bring Aboriginal cultural meaning to a wider audience. [8]

Heading south from the Tjilbruke Monument at Kingston Park, there are ten markers, located at the following places: [8]

- 1 Hallett Cove/Karildilla, at a reserve on Weerab Drive

- 2 Hallett Cove Karildilla, on Heron Way at the foreshore – site of the first spring

- 3 Port Noarlunga/Tainbarilla – at Tutu Wirra Reserve [11] – site of the second spring

- 4 Red Ochre Cove/Karkungga – site of the third spring

- 5 Port Willunga/Wirruwarrungga, Esplanade – site of the fourth spring

- 6 Sellicks Beach/Witawodli, Esplanade/Francis Street – site of the fifth spring

- 7 Carrickalinga Head/Karragarlangga, foreshore

- 8 Wirrina Cove Resort/Kongaratinga, entrance forecourt – site of the sixth spring

- 9 Rapid Bay/Patpangga, foreshore

- 10 Cape Jervis/Parawerangk, lookout car park

In 2009, a walkway was created to provide better access to Tulukudangga Spring at Kingston Park, with new interpretative signage. [8]

In the current City of Marion Reconciliation Plan, it is planned to "Collaborate with neighbouring Councils to promote the local Kaurna Tjilbruke Dreaming Tracks" in June 2022. [10]

The Tjilbruki Gateway is a modern art installation installed by the City of Marion at Warriparinga ("windy place by the river" [12] ), developed by Adelaide artists Margaret Worth , Sherry Rankine and Gavin Malone . A complex and highly symbolic artwork, it incorporates coloured sands from the Red Ochre Cove area, morthi ( tinder ) made from Stringybark tree trunks, and eucalypts . [9] After being planned since 1995, [10] official opening in October 1997 was attended by the Governor General of Australia , William Deane , Lowitja O'Donoghue , and several Kaurna representatives, and celebrated with traditional ceremony and dance. [9]

A federal government -funded reconciliation project in partnership with the City of Marion and the Kaurna community (Dixon and Williams clans) worked together to create a visitor and education centre for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to come together and reconcile their differences in the now metropolitan suburb of Marion, South Australia at a site known as site at Warriparinga. [12] This site at Bedford Park within the grounds of Warriparinga wetland and Sturt River , a traditional ceremonial camp site for Kaurna people. [13] Opened in 2001, [10] it was named the Warriparinga Interpretive Centre, subsequently becoming the Living Kaurna Cultural Centre . [14]

The Tjilbruke Dreaming is referred to in eleven sites around Adelaide city centre . The first might be the ibis and Aboriginal man represented in the Three Rivers Fountain , sculpted by John Dowie and first unveiled in 1963 in Victoria Square/Tarndanyangga . [8] [15] [16]

There is a plaque at Mt Lofty Summit with information about Tjilbruke. [3]

Designed by Kokatha [17] [18] artist Darryl Pfitzner "Mo" Milika , the outdoor art installation Yerrakartarta , meaning "at random" or "without design", was created with the assistance of several other artists including Kaurna/Ngarrindjeri artist Muriel van der Byl AM , [Note 2] ceramicists Jo Fraser, Stephen Bowers, and Jo Crawford from 1993 to 1994 on the forecourt of the Hyatt, now Intercontinental Hotel, on North Terrace in Adelaide. It was at the time "the largest Australian commission for an Aboriginal public artwork", [20] [21] and represents the history of the land through the forms of animals forms cut into the pavement, and, on the wall surrounding the area, a huge ceramic mural depicting the Tjillbruke Dreaming story. [17] [21]

Other commemorations include: [8]

- 1990s: Tjilbruke Dreaming Mural, Brompton Primary School

- 1997: Cultural Path Signal Box Park, Rosewater

- 1998: Tjilbruke Dreaming Mural, O'Sullivan Beach Primary School

- 2006: Warriparinga Walk Mural, under the Southern Expressway bridge at Warriparinga, Bedford Park

- 2002: Kaurna meyunna, Kaurna yerta tampendi – "Recognising Kaurna people and Kaurna land", Adelaide Festival Centre , with a carved stone to represent the springs

- 2007: Towilla Yerta Reserve, Port Willunga – pavement pattern includes a tear shape, and there is interpretive signage referring to the Dreaming

- 2009: Glow / Taltaityai , Walter Morris Drive, Port Adelaide , with representations of ibis and emus

- ↑ Williams is one of a number of Kaurna people, including Lewis O'Brien , Gladys Elphick , and Alice Rigney , who "are the driving force behind a cultural revival" and were responsible for introducing Kaura perspectives into the SA education curriculum. [3]

- ↑ Van der Byl's artwork was incorporated into the Australian fifty-dollar note released in 2018 [19] (still current as of 2020 [ update ] ).

Related Research Articles

The Kaurna people are a group of Aboriginal people whose traditional lands include the Adelaide Plains of South Australia. They were known as the Adelaide tribe by the early settlers. Kaurna culture and language were almost completely destroyed within a few decades of the British colonisation of South Australia in 1836. However, extensive documentation by early missionaries and other researchers has enabled a modern revival of both language and culture. The phrase Kaurna meyunna means "Kaurna people".

Victoria Square , also known as Tarntanyangga , is the central square of five public squares in the Adelaide city centre, South Australia.

The Port River is part of a tidal estuary located north of the Adelaide city centre in the Australian state of South Australia. It has been used as a shipping channel since the beginning of European settlement of South Australia in 1836, when Colonel Light selected the site to use as a port. Before colonisation, the Port River region and the estuary area were known as Yerta Bulti by the Kaurna people, and used extensively as a source of food and plant materials to fashion artefacts used in daily life.

Hallett Cove is a coastal suburb of Adelaide, South Australia located in the City of Marion 21 kilometres south of the Adelaide city centre. It has a population of more than 12,000 people. Adjoining suburbs are Marino to the north, Trott Park and Sheidow Park to the east and Lonsdale to the south.

O'Halloran Hill is a suburb in the south of Adelaide, South Australia, situated on the hills south of the O'Halloran Hill Escarpment, which rises from the Adelaide Plains and located 18 km from the city centre via the Main South Road. The suburb is split between the Cities of Marion and Onkaparinga, and it neighbours Happy Valley, Hallett Cove, Trott Park and Darlington. It includes a large area of farmland and commercial vineyards known as the Glenthorne Estate.

Marino is a coastal suburb in the south of Adelaide, South Australia that's surrounded by a conservation park and rugged coastline. This suburb is a brilliant place for families to develop an adventurous life in a unique setting with most houses having sea views and access to meandering public open spaces. The suburb even has its own working lighthouse. Marino's elevated position provides panoramic views of the ocean – Gulf St Vincent, the metropolitan beaches and Adelaide CBD. Marino has access to the North or South via Brighton Road, has two railway stations on the main Seaford Line and a host of walking and cycle trails to the neighbouring beaches and wine region. A community cooperative has purchased a restaurant building on the beachfront on Marine Parade. It's called Marino Rocks Social. The cooperative's first project is to run a cafe. The cooperative has 250 members, all with equal status, who have invested money or effort and is completely independent of other local community associations.

Kaurna is a Pama-Nyungan language historically spoken by the Kaurna peoples of the Adelaide Plains of South Australia. The Kaurna peoples are made up of various tribal clan groups, each with their own parnkarra district of land and local dialect. These dialects were historically spoken in the area bounded by Crystal Brook and Clare in the north, Cape Jervis in the south, and just over the Mount Lofty Ranges. Kaurna ceased to be spoken on an everyday basis in the 19th century and the last known native speaker, Ivaritji, died in 1929. Language revival efforts began in the 1980s, with the language now frequently used for ceremonial purposes, such as dual naming and welcome to country ceremonies.

Seacliff Park is a suburb of Adelaide partly in the City of Marion and the City of Holdfast Bay. The suburb is adjacent to South Brighton in the north, Seaview Downs to the east, Hallett Cove to the south, and Marino and Seacliff on its western side. The suburb is divided diagonally by Ocean Road, with the northern part of the suburb mainly residential, and the southern park partly occupied by a golf course and a quarry.

Port Noarlunga is a suburb in the City of Onkaparinga, South Australia. It is a small sea-side suburb, with a population of 2,918, about 30 kilometres to the south of the Adelaide city centre and was originally created as a sea port. This area is now popular as a holiday destination or for permanent residents wishing to commute to Adelaide or work locally. There is a jetty that connects to a 1.6 kilometres long natural reef that is exposed at low tide. The beach is large and very long and has reasonable surfing in the South Port area whose name is taken from its location - "South of the Port".

Warriparinga , also spelt Warriparingga , is a nature reserve comprising 3.5 hectares in the metropolitan suburb of Bedford Park, in the southern suburbs of Adelaide, South Australia. Also known as Fairford , Laffer's Triangle and the Sturt Triangle , Warriparinga is bordered by Marion Road, Sturt Road and South Road, and is traversed by the Sturt River as it exists from Sturt Gorge to travel west across the Adelaide Plains.

The District Council of Yankalilla is a local government area centred on the town of Yankalilla on the Fleurieu Peninsula in South Australia.

Carrickalinga is a small coastal town in South Australia about 60 kilometres (37 mi) south of Adelaide on the Fleurieu Peninsula overlooking Gulf St Vincent. The town has no shops, with the nearest being in Normanville, one kilometre away. Haycock Point separates two beaches, sometimes referred to as North Carrickalinga and South Carrickalinga beaches, both on Yankalilla Bay. Carrickalinga Creek discharges into the sea south of the town.

Sellicks Beach , formerly spelt Sellick's Beach , is a suburb in the Australian state of South Australia located within Adelaide metropolitan area about 47 kilometres (29 mi) from the Adelaide city centre. It is an outer southern suburb of Adelaide and is located in the local government area of the City of Onkaparinga at the southern boundary of the metropolitan area. It is known as Witawali or Witawodli by the traditional owners, the Kaurna people, and is of significance as being the site of a freshwater spring said to be created by the tears of Tjilbruke, the creator being.

Moana is an outer coastal suburb in the south of Adelaide, South Australia. The suburb is approximately 36.4 km from the Adelaide city centre. It lies within the City of Onkaparinga local government area, and neighbours the suburbs Seaford, Maslin Beach, Seaford Rise and Port Noarlunga It is divided into two by Pedler Creek and the associated sand dune reserve. The beach is often referred to as Moana Beach .

Yankalilla is an agriculturally based town situated on the Fleurieu Peninsula in South Australia, located 72 km south of the state's capital of Adelaide. The town is nestled in the Bungala River valley, overlooked by the southern Mount Lofty Ranges and acts as a service centre for the surrounding agricultural district.

Kingston Park is a small beachside suburb, 17 kilometres (11 mi) south of the Adelaide city centre. Kingston Park is within the City of Holdfast Bay and flanked by the neighbouring suburbs of Marino to the south and Seacliff to the north and east.

Hallett Cove Conservation Park is a protected area in the Australian state of South Australia located in the suburb of Hallett Cove on the coast of Gulf St Vincent about 22 kilometres south of the centre of the state capital of Adelaide.

Port Willunga is a semi-rural suburb of Adelaide, South Australia. It is known as Wirruwarrungga or Ruwarunga by the traditional owners, the Kaurna people, and is of significance as being the site of a freshwater spring said to be created by the tears of Tjilbruke, the creator being.

The Ingalalla Waterfalls , also known as Ingalalla Falls , is a cascade waterfall in the Australian state of South Australia, located in the locality of Hay Flat within the District Council of Yankalilla, on an unnamed creek on the Fleurieu Peninsula.

Wirrina Cove is a locality and holiday resort on the Fleurieu Peninsula, South Australia. It is located between the coastal towns of Second Valley and Normanville on Yankalilla Bay. The holiday resort was developed from around 1972, and is located about 90 kilometres (56 mi) south of Adelaide.

- 1 2 3 "Coastal Management Study, HallettCove, SA" (PDF) . Report No. R11‐008‐01‐01. Coastal Environment Pty Ltd. 14 June 2012 . Retrieved 15 November 2020 . Prepared for the City of Marion .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Amery, Rob (2016). Warraparna Kaurna!: Reclaiming an Australian language (PDF) . University of Adelaide Press. doi : 10.20851/kaurna . ISBN 978-1-925261-25-7 . Retrieved 17 November 2020 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Tjilbruke Story" . Port Adelaide Enfield . 12 August 2014 . Retrieved 16 November 2020 .

- ↑ "Map(s) of Kaurna Country" . Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi . The University of Adelaide . Retrieved 23 November 2020 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Kaurna Golden Rule Stories: Kaurna Stories: Tjilbruke" . The Abraham Institute . Retrieved 19 November 2020 . As told by Uncle Lewis O'Brien , Kaurna, [and] Katrina Karlapina Power, Kaurna Elder

- ↑ Schultz, Chester (18 March 2019). "Place Name Summary 7.01/07: 'Tjirbuki' or 'Tjirbuk'(Blowhole Beach)" . Adelaide Research & Scholarship . University of Adelaide . Retrieved 20 November 2020 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Malone, Gavin Damien Francis (2012). "Chapter 10: Kaurna Ancestor Being Tjilbruke: Commemorations" (PDF) . Phases of Aboriginal Inclusion in the Public Space in Adelaide, South Australia, since Colonisation (PhD). Flinders University . pp. 209–237 . Retrieved 17 November 2020 .

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Arts and culture" . City of Marion . 7 February 2018 . Retrieved 19 November 2020 .

- 1 2 3 4 City of Marion (2019). "City of Marion Reconciliation Milestones" (PDF) . Reconciliation Action Plan January 2020 – June 2023 (Report). pp. 8–9 . Retrieved 25 November 2020 .

- ↑ City of Onkaparinga (July 2017). Annual Report 2016-17 (Report). In December the stone cairn that marks the Tjirbruki/Tjilbruke Dreaming Track natural spring at Port Noarlunga was reinstated in the reserve atop Witton Bluff. This reserve has since been named Tutu Wirra Reserve, meaning 'lookout park' in the Kaurna language. The new location for the cairn was selected through engagement with a local Kaurna elder. The cairn at Port Noarlunga is one of four Tjirbruki/Tjilbruke markers along the coastline in our region.

- 1 2 "Living Kaurna Cultural Centre" . City of Marion . Retrieved 21 November 2020 .

- ↑ "Warriparinga" . City of Marion . City of Marion . Archived from the original on 3 July 2009 . Retrieved 25 July 2009 .

- ↑ "Living Kaurna Cultural Centre" . City of Marion . City of Marion . Archived from the original on 3 July 2009 . Retrieved 3 August 2009 .

- ↑ Elton, Jude. "Three Rivers Fountain" . Adelaidia . History Trust of South Australia . Retrieved 20 November 2020 .

- ↑ Hough, Andrew (30 July 2014). "Water turned on at Adelaide's historic Three Rivers Fountain in Victoria Square" . News Corporation. The City . Retrieved 14 December 2016 .

- 1 2 "Yerrakartarta" . The Rambling Wombat . 4 October 2017 . Retrieved 21 November 2020 .

- ↑ Milika, Darryl Pfitzner. "Introduction" . Aboriginal Art & Amateur Astronomy: A Confluence of Culture, Creativity, Art & Science . Retrieved 21 November 2020 .

- ↑ "Muriel Van Der Byl – in celebration" . Migration Museum . Retrieved 21 November 2020 .

- ↑ "Yerrakartarta Mural, Adelaide" . NixPixMix . 23 July 2012 . Retrieved 21 November 2020 .

- 1 2 Milika, Darryl Pfitzner. "Art Gallery" . Aboriginal Art & Amateur Astronomy: A Confluence of Culture, Creativity, Art & Science . Retrieved 21 November 2020 .

- Nganu and Tjilbruke: a tale of two heroes on YouTube (April 2020, video, 10 mins) "This short story is used with permission from the Monash University through partnership between Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi Aboriginal Corporation and South Australian Commission for Catholic Schools, in consultation with Kaurna Elder Uncle Lewis O’Brien."

- Malone, Gavin Damien Francis (2012). "Chapter 10: Kaurna Ancestor Being Tjilbruke: Commemorations" (PDF) . Phases of Aboriginal Inclusion in the Public Space in Adelaide, South Australia, since Colonisation (PhD). Flinders University . pp. 209–237. Contains many photographs of the markers on the trail, Yerrakartarta, the Tjirbruki Gateway, and other subjects, included the people involved.

- .mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em} v

- Ian Abdulla

- Jimmy Baker

- Maringka Baker

- Poltpalingada Booboorowie (Tom Walker)

- Iris Burgoyne

- Peter Burgoyne

- Shaun Burgoyne

- Hector Burton

- Kevin Buzzacott

- Nyakul Dawson

- Gladys Elphick

- Adam Goodes

- Ruby Hammond

- Ruby Hunter

- Tjungkara Ken

- Natascha McNamara

- Patty Mills

- Lewis O'Brien

- Lowitja O'Donoghue

- Frances Rings

- Nura Rupert

- Tauto Sansbury

- Eileen Yaritja Stevens

- David Unaipon

- James Unaipon

- Gavin Wanganeen

- Natasha Wanganeen

- Ginger Wikilyiri

- Norah Wilson

- Chad Wingard

- Tjayanka Woods

- Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara

- Aṉangu schools

- Gerard Community Council

- Kupa Piṯi Kungka Tjuṯa

- Maralinga Tjarutja

- List of Aboriginal schools

- Aborigines' Friends' Association

- Australian frontier wars

- Avenue Range Station massacre

- Hindmarsh Island Bridge controversy ( Royal Commission )

- History of South Australia

- Maria massacre

- Waterloo Bay massacre

Willunga Basin

Photography, tjilbruke dreaming.

Tjilbruke Dreaming story The tale of Tjilbruke's journey down the east coast of Wongga Erlo/Gulf St Vincent is the best known of all Kaurna Dreaming stories, and has become a symbol of renewal of the Kaurna culture, although it was first recorded from Ngarrindjeri sources by Tindale and later Ronald and Catherine Berndt. It was recorded by Tindale over a period of many years up to 1964, but it was not until 1987 that he published the most complete version hitherto published, as The Wanderings of Tjirbruki: a tale of the Kaurna People of Adelaide. The story starts with an emu (kari) hunt by three one men, Kulultuwi, Jurawi and Tetjawi. They were all nephews of Tjilbruke, but Kulultuwi had a special relationship to his uncle, as he was the son of his sister, and known as his nangari; the other two were his half-brothers. Tjilbruke was responsible for Kulutwi, as an uncle as well as a father, to help him grow up correctly and do the right thing. While the young men went hunting in the Tarndanya (Adelaide) area, across Mikkawomma (the plains) to Yerta Bulti (Port River estuary), driving the birds up Mudlangga (Le Fevre Peninsula), Tjilrbuke went fishing at Witu-wattingga (the Brighton area). After finishing his fishing, he set up camp at Tulukudangga/Tulukudank (Kingston Park and then started tracking an emu southwards. When Kulultuwi returned to the area, he found himself tracking the same emu as his uncle, which he was forbidden to do. However he killed the emu, and Tjilbruke, although initially angry, forgave him when he gave him some of the emu meat. (In one version of the story, although Kulultuwi was not supposed to have killed the kari ahead of his uncle, Tjilbruke gave him permission to do so, as long as he gave him some of the meat.) While Kulultuwi was cooking the emu meat over a fire, Jurawi and Tetjawi killed him with their spears, as punishment for his breaking the law of the clan. The brothers took the body to their clan campsite at Warriparri (Sturt River) and told them the story, and they started to dry the body with smoke, as custom dictated. After Tjilbruke found out, he was very upset, and speared the two nephews to death (in retaliation, applying the law, being a man of the law), before carrying Kulultuwi's body to Tulukudangga, where an inquest and ceremony to complete the smoking of the body was held. The story goes on to tell of how six freshwater springs were created by Tjilbruke's tears, as he carried the body of his dead nephew from Warriparri across to the coast and southwards past Aldinga Beach and onto the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula to Rapid Bay. The Dreaming includes locations in several geographic areas: the Adelaide Plains, the Fleurieu Peninsula, on the south coast at Rosetta Head (The Bluff) near Victor Harbour, and also in the Adelaide Hills at Brukunga; so it takes in Ramindjeri and Peramangk country. After Kulultuwi's body had been smoked and dried, Tjilbruke picked up the body and carried it firstly to Tulukudangga/Tulukudank. Here some versions of the story diverge slightly; one says that he wept at this point and his tears created this spring, while another says that Tulukudangga was an existing spring at that place. From Tulukudangga, Tjilbruke carried Kulultuwi's body all the way down the eastern side of Gulf St Vincent and onto and down the west coast of the Fleurieu Peninsula. At sunset every night of his journey Tjilbruke cried over his nephew's body, and his tears transformed into freshwater springs at six locations: Kareildung (Hallett Cove) Tainbarang (Port Noarlunga) Potartang (Red Ochre Cove, near Moana Beach) Ruwarunga (Port Willunga) Witawali (Sellicks Beach) Kongaratinga (near Wirrina Cove, or Yankalilla) He arrived at a cave (perki) at Rapid Bay, near Cape Jervis, and then emerged from underground at Wateira nengal (Mount Hayfield) and created yellow ochre. He walked on to Lonkowar (The Bluff/Rosetta Head, in Ramindjeri country), near Victor Harbor, where he killed a grey currawong, rubbed its fat onto his body and tied its feathers onto his arms, before transforming himself into a glossy ibis (or other wading bird; in some sources, a blue crane) as his spirit left his body. His body became the pyrite outcrop at Brukunga. Saddened by these events Tjilbruke decided he no longer wished to live as a man. His spirit became a bird, the Tjilbruke (Glossy Ibis), and his body became a martowalan (memorial) in the form of the baruke (iron pyrites) outcrop at Barrukungga, the place of hidden fire (Brukunga - north of Nairne in the Adelaide Hills). Tjilbruke was a master at fire-making.

The Natural Wonder

Willunga basin conservation.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

Mudlangga to Yertabulti track

Tjilbruke/Tjirbruki Story

In this telling of the Tjilbruke story Karl Telfer and Gavin Malone use the spelling “Tjirbruki” as recorded by Tindale. Elsewhere in this project the spelling utilised is “Tjilbruke”. Both spellings are recognised.

Tjirbruki is a Bukkiana meyu Ancestor being of the Kaurna meyunna people and was from the time after the sea waters had risen and created Wongga Yerlo Gulf St Vincent . Kaurna Yerta Parngkarra or Kaurna Tribal Country extends from Cape Jervis to the south of Adelaide, to Crystal Brook to the north and west of Piko-illya in the Mount Lofty Ranges to the coast of Gulf Saint Vincent. Their ancestral lands include the Adelaide Plains and the city of Adelaide.

Tjirbruki was living at one of the summer camping places near Patpangga (Rapid Bay) with his clan when a kari emu hunt was organised in lands to the north, in Tarndanya (the Adelaide region) as there were many kari there. His three nephews Kulultuwi, Jurawi and Tetjawi and others went on the hunt. Kulultuwi was Tjirbruki’s nangari, sister's son, and much loved by him. Jurawi and Tetjawi were from other mothers.

Tjirbruki did not go on the hunt but moved his camp to Witu-wattingga (Brighton region) to fish, catching big hauls of kurari, also called darawe beaked salmon . The kari hunters went north and moved across Mikkawomma, the open plains between Tarndanya (Adelaide area) and Yerta Bulti (Port Adelaide area) to drive the birds towards Mudlunga Nose place (Le Fevre Peninsula) and trap them at the tip of the peninsula. Whilst some birds got away, the hunt was successful.

Meanwhile Tjirbruki moved camp to Tulukudangga, a fresh water spring near the beach (at Kingston Park), and then went inland to hunt kari for himself and saw the fresh tracks of a male bird which he decided would be his. According to custom, the first to sight the presence of game had the right to take it. After finishing his fishing Tjirbruki followed the kari’s tracks south towards Witawodli (Sellicks Beach) where they turned inland. Tjirbruki decided that the bird would later come back towards the coast so he travelled further south to intercept it.

Kulultuwi had also come back down south and saw the kari’s tracks, followed them and then killed the bird. But he crossed Tjirbruki’s footprints and in doing so broke the lore, he should have known it was Tjirbruki’s because of his footprints. Tjirbruki realised the bird was not coming his way and began to back track. He saw smoke from a fire and headed that way, soon hearing Kulultuwi singing whilst a cooking fire was being prepared with Jurawi and Tetjawi. Tjirbruki confronted Kulultuwi about killing his bird. Kulultuwi said he was sorry and apologised, saying he had not realised it was his uncle’s bird and so offered him the meat. As Tjirbruki had some kangaroo meat with him he took only some of the kari and went on his way. He had forgiven Kulultuwi for his mistake.

As Kulultuwi was finishing the cooking, he checked its progress and a burst of steam from the kari blinded him. Jurawi and Tetjawi rushed in and speared and killed Kulultuwi, reasoning that they had done so because of their elder brother’s breaking the law in killing their uncle’s bird. They then shared the meat with their own clan and told them what had happened. The clan then started smoke drying Kulultuwi’s body before later taking it to Warriparri (Sturt River) to continue drying the flexed body on a rack over a fire.

But the brothers then made up a story to cover up what they had done, that Kulultuwi, in fear of Tjirbruki’s anger, had gone elsewhere to hunt kari. Tjirbruki soon heard the false story and also asked people of the Witjarlung clan to pass on his forgiveness to Kulultuwi if they saw him. Although they knew of his death, the Witjarlung concealed it from Tjirbruki who then went looking for his nephew. Eventually, near where he had last seen him, he came across sugar ants on the track and saw they were carrying human hair and blood and red ochre. He realised his nephew was dead and then saw were the body had been and the smoke drying had started.

Tjirbruki, being a man of the law, had to decide if Kulultuwi had been lawfully killed. He determined Kulultuwi had not been killed within the law and that he had to avenge the murder. He went and obtained some good spears and travelled north along the hills before making his way back to the coast and found out that there was a big camp at Warriparri. He first went to Witu-wattingga to rest and was greeted there by the two brothers who still deceived him about Kulultuwi’s death, blaming it on others who may have been Peramangk (from the Adelaide Hills). Tjirbruki knew they were lying but did not say so, he went along with their deception. The next day they went inland to the camp at Warriparri (where Kulultuwi’s body was still being smoke-dried). In the evening they danced for the old man Tjirbruki who then sang the camp to sleep. He made sure all were asleep by calling out but there was no response.

Tjirbruki was a master at fire-making. He used powdered morthi bark stringybark tree as tinder and set it round the hut they were sleeping inwith piles of grass, leaving only a small gap at the entrance. Then, using a baruke iron pyrites stone and a piece of paldari flintstone , he started fires at each pile of morthi tinder, telling the fire to blaze up quickly. He cried out loudly, ‘You are getting burned! Camp on fire'. When Jurawi came out he speared him with a wundi dread-spear , and then the same to Tetjawi. When he knew they were dead he pulled out his spears.

In the morning Tjirbruki carried Kulultuwi’s partly smoked dried body to Tulukudangga, the fresh water spring on the beach (at Kingston Park) to complete the smoking and for an inquest to be held. Many people gathered for the ceremony and the names of the two killers and the way Kulultuwi was killed were confirmed.

Tjirbruki then wrapped Kulultuwi’s remains into a compact parcel and headed south to Patpangga (Rapid Bay) to place the remains in a perki cave . Along the journey he stopped several times to rest and overwhelmed by sadness at his favourite nephews death he wept and where his mekauwe tears dropped to the ground a spring of fresh water welled up. That is how the freshwater springs along the coast at Karildilla (Hallet Cove), Tainbarilla (Port Noarlunga), Karkungga (Red Ochre Cove), Wirruwarrungga (Port Willunga), Witawodli (Sellicks Beach), and Kongaratinga (near Wirrina Cove) came to be. And each place became a camping place.

Along his journey south Tjirbruki also punished others who had deceived him about Kulultuwi’s death. He walked into the offender’s camp and speared four men, Ngarakkani, Nenaratawi, Limi, and Tulaki in the leg as retribution; it was the right punishment to spear people in the leg. The people in the camp knew Tjirbruki was serious and took fright, some jumping into the sea to become various kinds of shark which we now know as Ngarakkani Gummy Shark , Nenaratawi, Southern Fiddler Ray or Banjo Shark , Limi Cobbler Carpet Shark and Tulaki, Bronze Whaler or Cocktail Shark . These fish became the totems of the Witjarlung clan. Any others left in the camp also fled and they turned into birds.

Tjirbruki was then there alone, satisfied with what he had done and after resting, continued his journey. When he finally came to the right cave he went into the darkness and found a rock ledge to make a small platform on which to place Kulultuwi’s remains. He then went further in, travelling to the depths of the cave before coming to an opening further inland at Wateira nengal (Mt Hayfield). There he emerged covered in yellow dust which at the foot of the hill he shook off, forming yellow ochre at that place.

Saddened by these events and feeling old, Tjirbruki decided he no longer wished to live as a man. He travelled to Lonkowar (Rosetta Head) in Ramindjeri Country where he decided what to do. He saw a grey currawong, stalked and killed it and then rubbed its fat on his body and tied its feathers to his arms with hair string. He took to the sky and his spirit became a bird, tjirbruki (Glossy Ibis). His body became a martowalan memorial in the form of the baruke iron pyrites outcrop at Barrukungga, the place of hidden fire (Brukunga – north of Nairne in the Adelaide Hills).

Karl Winda Telfer Bio

Karl Winda Telfer is a senior Kaurna cultural custodian for his clan countries from his grand fathers tribal lands within the Adelaide plains Mullawirra (dry forest country) Pangkarra Kaurna Meyunna (people) and his grand mothers tribal lands Mullamai (dry food country) Pangkarra in Narrunga Country, Yorke Peninsula. He is a senior custodian of ceremony, story teller, cultural designer, place maker, educator and visual artist. Karl has initiated many innovative bi-cultural projects over many years educating and engaging the wider community through ecological, cultural and spiritual renewal practises and ways of understanding country and First Nations cultures. Karl is a knowledge bearer of the peace lore fire of Tjirbruki for which his tribal family group are cultural bearers, having started this work of generational renewal in the early 1980s.

Karl brings many people together through ways of understanding the spirit of humanity. He has been invited to speak and share culture at many local, national and international forums. In 1992 he was invited to participate in the Tracking Project, a seven year forum of international educators and Native elders from around the world to design a series of teachings, which connect communities and individuals directly to the natural world.

In 1993 Karl co-founded the Tjilbruke Dancers and in 1996 founded the Paitya Dance Group , which interweave Kaurna Palti Meyunna land knowledge systems and culture through language, stories, song, ceremony and ritual. He has shared, presented and represented his culture internationally. He was the inaugural Aboriginal Associate Director for the 2002 Adelaide Festival of Arts where he co-artistically produced and directed the global ceremony of peace, Kaurna Palti Meyunna , in Tarndanyungga /Victoria Square and in 2008 was the inaugural cultural and creative producer of the Spirit Festival.

Karl has collaborated with artists, landscape architects and architects on major public space art, design and place making projects, in particular the Victoria Square Tarndanyangga Regeneration Master Plan with Taylor Cullity Lethlean. He was awarded the President’s Prize by the SA Chapter, Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, for his contribution to public space design. He has been a member of several boards and committees and is currently (2014) a member of the Adelaide and the Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board.

163 St Vincent Street | PO Box 110

Port Adelaide SA 5015

(08) 8405 6600 | Email Us

Visitor Information Centre

66 Commercial Road

"We acknowledge and pay respect to the Traditional Owners of the land on which we stand, the Kaurna People of the Adelaide Plains. It is upon their ancestral lands that the Port Adelaide Enfield Council meets. It is also the Place of the Kardi, the Emu, whose story travels from the coast inland. We pay respect to Elders past, present and emerging. We respect their spiritual beliefs and connections to land which are of continuing importance to the living Kaurna People of today. We further acknowledge the contributions and important role that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to play within our shared community."

‘What country have you walked?’ Why all Australians should walk an Indigenous heritage trail

Professor of Writing, Flinders University

Contributor

Tour guide, Indigenous Knowledge

Disclosure statement

Stephen Muecke receives funding from The Australian Research Council. He co-authored The Children’s Country: Creation of a Goolarabooloo Future in North-West Australia with Paddy Roe, who is mentioned in this essay.

Daniel Roe is the general manager of the Goolarabooloo/Millibinyarri Indigenous Corporation and leads the Lurujarri Heritage Trail.

Flinders University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

The Goolarabooloo community in Broome has been running the Lurujarri Heritage Trail for over 30 years. In July each year, tourists are welcomed by the Roe family, and embark on an eight-day trek.

Swags and tents are piled on the truck, so the walkers only have to carry a day pack. They soon pass the famous Cable Beach where less adventurous tourists are basking in the sun, and continue their walk along the beach admiring the contrast of aquamarine ocean and red pindan cliffs.

On trail, the colonial power dynamic between settler and Indigenous communities is turned on its head. The Goolarabooloo express their sovereignty (never ceded) by welcoming visitors onto their Country.

This kind of tourism is a rare, life-changing experience. What is special about the Lurujarri Trail is the participation of the Roe family. “Over eight days, we become friends,” tour leader Daniel Roe tells the group.

Trailblazing

It was Daniel’s late great-grandfather, Paddy Roe , who had the idea for the trail in 1987. I had written a couple of books with him, and we were working on a third at the time, which I have only just delivered on: The Children’s Country .

He wanted the text to document and protect Country from developers and miners. But it turned out the trail was a better idea. When Woodside Energy and the Western Australian government wanted to build a huge gas hub in the middle of the trail, at Walmadany, James Price Point, over ten years ago, it was the Goolarabooloo that stood in the way, and eventually won the battle .

Hundreds of people had walked the trail over the years and some came back to help in the campaign. They had developed a kind of gut feeling for Country the Goolarabooloo call liyan .

Read more: Without James Price Point, what now for Browse Basin gas?

Extractive industries

White Europeans only arrived in West Kimberley at the end of the 19th century, so elders like Paddy Roe , who lived from about 1912 to 2001, saw their arrival unfold.

In recent years, stark divisions over mining money have emerged in the Aboriginal community and Native Title determinations have exacerbated the divisions. The Goolarabooloo did not get any Native Title rights, as their neighbours did. Some speculate their opposition to the gas had a lot to do with it .

In a sense, the walking trail is land rights by other means. They are maintaining their knowledge and passing it on.

Dreaming stories (called bugarrigarra , the law) connect communities and follow old trade routes, down through the Western Desert via Uluru into southern parts, where the local pearl-shell used to be be traded for ochre, native tobacco or new song cycles.

Read more: Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is a must-visit exhibition for all Australians

There are dozens of Aboriginal walking tracks across Australia: well-known are the Larapinta in Central Australia, the Bundian Way between Targangal (Kosciuszko) and Bilgalera on the coast near Eden, and Mungo Aboriginal Discovery Tours.

But it is hard to find another with the Lurujarri Heritage Trail’s family involvement, ocean swimming, bush tucker, and the most extensive set of dinosaur footprints in Australia.

Read more: Friday essay: how our new archaeological research investigates Dark Emu's idea of Aboriginal 'agriculture' and villages

More Indigenous-led walking tracks could trace storied landmarks.

In Kaurna Country around Adelaide, there is the story of Tjilbruke . This ancestor was a law man whose nephew Kulultuwi was hunting emu that were forbidden to him.

Tjilbruke was prepared to overlook the transgression, but Kulultuwi’s half-brothers speared him. Tjilbruke, in mourning, carried the body of his nephew down the coast, stopping to weep at various points where there are now freshwater springs.

Read more: Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned

Walking schools

There is increasing awareness of how Indigenous knowledges are relevant to caring for Country .

“Things must go both ways,” Paddy Roe used to say to me.

He had already experienced practices that saw knowledge transfer going one way. People would ask him about his Country in order to exploit it, for water, for pasture, for pearl-shells and now for gas and oil.

Walking tracks can teach what each territory is capable of sustaining. The people further down the track know their Country is that little bit different and what it is capable of. These pathways connect up, and knowledge transforms along the way.

People often ask, “What school did you go to?” Perhaps one day, in Australia, they will ask, “what Country have you walked?”

- Indigenous land

Scheduling Analyst

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Yankalilla and District Historical Society Inc.

Aboriginal Peoples

Tjirbruki munaintya (tjilbruke dreaming).

The Tjilbruke Dreaming extends geographically from the Adelaide Plains near Warriparinga, down the Fleurieu Peninsula to Cape Jervis, and across into country of the Ramindjeri (Rosetta Head/The Bluff) and Peramangk people (Brukunga/Adelaide Hills).

The story of Tjilbruke. Tjilbruke, also spelt Tjirbruki, is an important creation ancestor for Kaurna Meyunna. Several versions of the Tjirbruki Munaintya Tjirbruki Dreaming are available on the internet and in various publications with varying amounts of detail and accuracy.

Karl Winda Telfer, cultural custodian, and Gavin Malone, cultural geographer have written a Tjirbruki Munaintya Summary (Telfer & Malone ) (PDF 130KB) which can be found on their CRED: Cultural Research Education Design website.

Dedication of plaque at Carrickalinga Head. On Sunday afternoon, 26 February 2023, Karl Winda Telfer, Burka, Mullawirra meyu (Senior Man, Dry forest people) led a moving dedication ceremony for a replacement plaque at Carrickalinga Head, one of the sites on the Tjilbruke Dreaming Track. The South Australian Governor, Her Excellency, Francis Adamson AO, spoke at the event, emphasising the importance of maintaining and preserving Aboriginal history of the region, delivering the first part of her address in Kaurna Meyunna language.

Karl Telfer, dedication ceremony Carrickalinga Head

Tjilbruke Dreaming Track replacement plaque

The memorialisation of the Tjilbruke Track was part of a life’s work of more than 50 years for Nganki Burka Mekauwe (Senior Woman of Water) Kaurna Meyunna yerta (Kaurna Meyunna country), the late Georgina Williams, Karl Telfer’s mother.

Named Aboriginal Places on the Western Fleurieu

From presentation held Saturday 21 May 2022, Yankalilla Uniting Church Hall

For those who expressed an interest on the day, here are the references mentioned during the presentation:

The full Place Name Summary (PNS) includes downloadable essays by Chester Schultz:

Introduction to Kaurna Place Names essays project

The Geography of Language Groups around Fleurieu Peninsula at First Contact

Ask the right question, then look everywhere. (Presentation on Chester’s research methods)

The Kaurna Place Names website, by KWP (Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi) features a Google map with index & popup windows of public information. See also the KWP website at www.kaurnawarra.org.au

Coast Scene near Rapid Bay. Sunset Natives Fishing with nets, c1847. G. F. Angas AGSA_sml (1)

Reconciliation

Ngadlu Padninthi Kumangka - We Walk Together

‘ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this story contains images, voices, and names of deceased persons .’

The Faculty of the Professions commissioned this mural in the spirit of reconciliation.

The design was developed by the artists Narisha Cash, a descendant of the Jingliand Mudburra people, and Allan Sumner a Ngarrindjeri, Kaurna, and Yankunytjatjaraman, in conjunction with a group of Kaurna students, linguists and Elders, including Dr Lewis Yerloburka O’Brien.

The mural locates the University of Adelaide on the Karrawirra Pari, Torrens River, as it runs between the foothills and the sea, and acknowledges thousands of years of Kaurna people meeting and living on this land. The design features Tarnta, the Red Kangaroo, the distinctive red and white Kaurna shield, and a coolamon with water flowing from it, symbolising men and women and their equality.

The mural depicts a Kaurna ancestor looking toward the sun, and ibises offering guidance and protection. The ibises reflect the Kaurna Dreaming story of Lawman Tjilbruke, and his journey down south. When Tjilbruke’s nephew died, in a state of grief Tjilbruke turned himself into an ibis and his tears formed many of the springs between Warriparingga, Marion, and Nangarang, Cape Jervis, known as the Tjilbruke Trail.

Ngadlu Padninthi Kumangka mural is located behind Nexus 10 on North Terrace. The mural is proudly supported by the Adelaide City Council through their Arts and Cultural Grants Program.

Tjilbruke Monument

- Aboriginal Culture & Heritage

- Brighton Beachfront Holiday Park

- Artist Register

- Busking in Holdfast Bay

- Bay Discovery Centre - Group Bookings & Resources

- Expression of Interest

- Tiati Wangkanthi Kumangka (Truth-Telling Together)

- Boy Phoenix

- On the Beach

- The Road to Federation

- Casa Paquita

- Sand Castles

- St John at the Beach

- Getting Here & Around

- Our History

- Holdfast Bay History Centre Research Enquiry Form

- History Collection

- Historical Places

- Glenelg Air-Raid Shelter

- Holdfast Bay History Centre

- Kid's Stuff

- Parks, Reserves and Beaches

- Adelaide Beaches

- Jetty Road, Glenelg

- The Broadway

- Public Facilities

- Glenelg to Seacliff Coastal Walk

- History Festival

- Play at the Bay

- Days at the Bay

The monument was commissioned in 1972 by the local weekly newspaper, The Sunday Mail, in conjunction with the South Australian Museum. The commission followed a series of articles about the Kaurna people and the Tjilbruke Dreaming by Sunday Mail journalist William Reschke in 1971 (Sunday Mail, 1971a, b, c, d; Reschke, 1972). Together with Robert Edwards, then Curator of Anthropology at the South Australian Museum, Reschke formed the Tjilbruke Monument Committee. The aim of the commemorative project, which was to be funded through a public appeal for donations.

Public Arts Nearby

More than ever, we need to remember to 'Hang Loose' and connect with the ocean, with nature and with each other. It's good for the soul. This sculpture was purchased by Council from the 2015 Brighton Jetty Sculptures Event and installed along the Esplanade as an iconic beachside work of art.

Purchased from the 2019 Brighton Jetty Sculptures Festival.

Located on the southern side of the Brighton Jetty.

An aluminium spiraling structure that captures the movement of water and wind.

Artist Violet Cooper has a love for sea shells and creates works of art collected from across the seas to our very own Brighton Beach. The lettering has been made by hand from clay (with love) and reads 'I see the sea & the sea sees me'

The artwork invites viewers to see the sea from a different perspective and to see the sea looking right back at you.

- ENVIRONMENT

Published on 28 April 2021

A mark of respect for Georgina Williams

A ceremony at Port Noarlunga has paid tribute to the work of Senior Kaurna Meyunna Tribal Woman, Georgina Williams, at the reawakening of the sacred Dreaming story of Tjilbruke.

In April, at a Port Noarlunga reserve overlooking the sea, people gathered for a ceremony steeped in truth and respect.

A plaque was renewed, recognising the sacred, cultural and spiritual importance of the Tjilbruke Dreaming Track.

The Tjilbruke Dreaming Track is a significant ancestral journey along Adelaide’s coast and the Reserve on the corner of the Esplanade and Anderson Avenue is home to one of 10 cultural markers. The markers recognise the tears of Tjilbruke that formed the natural springs — an integral part of the Dreaming story.

The important ceremony also acknowledged 50 years of work and activism that Senior Kaurna Meyunna Woman Georgina Williams has dedicated to her people, her culture and the broader Onkaparinga community.

City of Onkaparinga Mayor Erin Thompson attended the ceremony and spoke of the importance of upholding the cultural values of the Traditional Owners of the City of Onkaparinga region.

“I’m proud to stand here today on behalf of our city to acknowledge the 50 years of work by Senior Tribal Woman Georgina Williams – Woman of Water because it’s the right thing to do,” Mayor Thompson said.

“A life’s work dedicated to your family, your people, your culture and to the reawakening of this sacred Dreaming story, so your people could come home to country.

“Georgina’s resolve has been second to none. She has maintained her path with unwavering strength and wisdom. She has always stayed true to her convictions with future generations in mind.

“The Tjilbruke Dreaming Track was officially opened on 18 December 1986, supported by the Minister for Environment and Planning, Susan Lenehan.

“We’re listening in a deeper way, which has opened a new way of understanding this story for myself and my fellow councillors.

“I stand here today in truth and respect. I stand here today as Mayor of the City of Onkaparinga. I stand here today to admit that we haven’t always gotten it right.