- [ May 9, 2024 ] Moon Phases: What They Are & How They Work Solar System

- [ April 3, 2024 ] Giordano Bruno Quotes About Astronomy Astronomy Lists

- [ March 28, 2024 ] Shakespeare Quotes: Comets, Meteors and Shooting Stars Astronomy Lists

- [ March 28, 2024 ] Shakespearean Quotes About The Moon Astronomy Lists

- [ November 30, 2022 ] The Night Sky This Month: December 2022 Night Sky

5 Bizarre Paradoxes Of Time Travel Explained

December 20, 2014 James Miller Astronomy Lists , Time Travel 58

There is nothing in Einstein’s theories of relativity to rule out time travel , although the very notion of traveling to the past violates one of the most fundamental premises of physics, that of causality. With the laws of cause and effect out the window, there naturally arises a number of inconsistencies associated with time travel, and listed here are some of those paradoxes which have given both scientists and time travel movie buffs alike more than a few sleepless nights over the years.

Types of Temporal Paradoxes

The time travel paradoxes that follow fall into two broad categories:

1) Closed Causal Loops , such as the Predestination Paradox and the Bootstrap Paradox, which involve a self-existing time loop in which cause and effect run in a repeating circle, but is also internally consistent with the timeline’s history.

2) Consistency Paradoxes , such as the Grandfather Paradox and other similar variants such as The Hitler paradox, and Polchinski’s Paradox, which generate a number of timeline inconsistencies related to the possibility of altering the past.

1: Predestination Paradox

A Predestination Paradox occurs when the actions of a person traveling back in time become part of past events, and may ultimately cause the event he is trying to prevent to take place. The result is a ‘temporal causality loop’ in which Event 1 in the past influences Event 2 in the future (time travel to the past) which then causes Event 1 to occur.

This circular loop of events ensures that history is not altered by the time traveler, and that any attempts to stop something from happening in the past will simply lead to the cause itself, instead of stopping it. Predestination paradoxes suggest that things are always destined to turn out the same way and that whatever has happened must happen.

Sound complicated? Imagine that your lover dies in a hit-and-run car accident, and you travel back in time to save her from her fate, only to find that on your way to the accident you are the one who accidentally runs her over. Your attempt to change the past has therefore resulted in a predestination paradox. One way of dealing with this type of paradox is to assume that the version of events you have experienced are already built into a self-consistent version of reality, and that by trying to alter the past you will only end up fulfilling your role in creating an event in history, not altering it.

– Cinema Treatment

In The Time Machine (2002) movie, for instance, Dr. Alexander Hartdegen witnesses his fiancee being killed by a mugger, leading him to build a time machine to travel back in time to save her from her fate. His subsequent attempts to save her fail, though, leading him to conclude that “I could come back a thousand times… and see her die a thousand ways.” After then traveling centuries into the future to see if a solution has been found to the temporal problem, Hartdegen is told by the Über-Morlock:

“You built your time machine because of Emma’s death. If she had lived, it would never have existed, so how could you use your machine to go back and save her? You are the inescapable result of your tragedy, just as I am the inescapable result of you .”

- Movies : Examples of predestination paradoxes in the movies include 12 Monkeys (1995), TimeCrimes (2007), The Time Traveler’s Wife (2009), and Predestination (2014).

- Books : An example of a predestination paradox in a book is Phoebe Fortune and the Pre-destination Paradox by M.S. Crook.

2: Bootstrap Paradox

A Bootstrap Paradox is a type of paradox in which an object, person, or piece of information sent back in time results in an infinite loop where the object has no discernible origin, and exists without ever being created. It is also known as an Ontological Paradox, as ontology is a branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of being or existence.

– Information : George Lucas traveling back in time and giving himself the scripts for the Star War movies which he then goes on to direct and gain great fame for would create a bootstrap paradox involving information, as the scripts have no true point of creation or origin.

– Person : A bootstrap paradox involving a person could be, say, a 20-year-old male time traveler who goes back 21 years, meets a woman, has an affair, and returns home three months later without knowing the woman was pregnant. Her child grows up to be the 20-year-old time traveler, who travels back 21 years through time, meets a woman, and so on. American science fiction writer Robert Heinlein wrote a strange short story involving a sexual paradox in his 1959 classic “All You Zombies.”

These ontological paradoxes imply that the future, present, and past are not defined, thus giving scientists an obvious problem on how to then pinpoint the “origin” of anything, a word customarily referring to the past, but now rendered meaningless. Further questions arise as to how the object/data was created, and by whom. Nevertheless, Einstein’s field equations allow for the possibility of closed time loops, with Kip Thorne the first theoretical physicist to recognize traversable wormholes and backward time travel as being theoretically possible under certain conditions.

- Movies : Examples of bootstrap paradoxes in the movies include Somewhere in Time (1980), Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989), the Terminator movies, and Time Lapse (2014). The Netflix series Dark (2017-19) also features a book called ‘A Journey Through Time’ which presents another classic example of a bootstrap paradox.

- Books : Examples of bootstrap paradoxes in books include Michael Moorcock’s ‘Behold The Man’, Tim Powers’ The Anubis Gates, and Heinlein’s “By His Bootstraps”

3: Grandfather Paradox

The Grandfather Paradox concerns ‘self-inconsistent solutions’ to a timeline’s history caused by traveling back in time. For example, if you traveled to the past and killed your grandfather, you would never have been born and would not have been able to travel to the past – a paradox.

Let’s say you did decide to kill your grandfather because he created a dynasty that ruined the world. You figure if you knock him off before he meets your grandmother then the whole family line (including you) will vanish and the world will be a better place. According to theoretical physicists, the situation could play out as follows:

– Timeline protection hypothesis: You pop back in time, walk up to him, and point a revolver at his head. You pull the trigger but the gun fails to fire. Click! Click! Click! The bullets in the chamber have dents in the firing caps. You point the gun elsewhere and pull the trigger. Bang! Point it at your grandfather.. Click! Click! Click! So you try another method to kill him, but that only leads to scars that in later life he attributed to the world’s worst mugger. You can do many things as long as they’re not fatal until you are chased off by a policeman.

– Multiple universes hypothesis: You pop back in time, walk up to him, and point a revolver at his head. You pull the trigger and Boom! The deed is done. You return to the “present,” but you never existed here. Everything about you has been erased, including your family, friends, home, possessions, bank account, and history. You’ve entered a timeline where you never existed. Scientists entertain the possibility that you have now created an alternate timeline or entered a parallel universe.

- Movies : Example of the Grandfather Paradox in movies include Back to the Future (1985), Back to the Future Part II (1989), and Back to the Future Part III (1990).

- Books : Example of the Grandfather Paradox in books include Dr. Quantum in the Grandfather Paradox by Fred Alan Wolf , The Grandfather Paradox by Steven Burgauer, and Future Times Three (1944) by René Barjavel, the very first treatment of a grandfather paradox in a novel.

4: Let’s Kill Hitler Paradox

Similar to the Grandfather Paradox which paradoxically prevents your own birth, the Killing Hitler paradox erases your own reason for going back in time to kill him. Furthermore, while killing Grandpa might have a limited “butterfly effect,” killing Hitler would have far-reaching consequences for everyone in the world, even if only for the fact you studied him in school.

The paradox itself arises from the idea that if you were successful, then there would be no reason to time travel in the first place. If you killed Hitler then none of his actions would trickle down through history and cause you to want to make the attempt.

- Movies/Shows : By far the best treatment for this notion occurred in a Twilight Zone episode called Cradle of Darkness which sums up the difficulties involved in trying to change history, with another being an episode of Dr Who called ‘Let’s Kill Hitler’.

- Books : Examples of the Let’s Kill Hitler Paradox in books include How to Kill Hitler: A Guide For Time Travelers by Andrew Stanek, and the graphic novel I Killed Adolf Hitler by Jason.

5: Polchinski’s Paradox

American theoretical physicist Joseph Polchinski proposed a time paradox scenario in which a billiard ball enters a wormhole, and emerges out the other end in the past just in time to collide with its younger version and stop it from going into the wormhole in the first place.

Polchinski’s paradox is taken seriously by physicists, as there is nothing in Einstein’s General Relativity to rule out the possibility of time travel, closed time-like curves (CTCs), or tunnels through space-time. Furthermore, it has the advantage of being based upon the laws of motion, without having to refer to the indeterministic concept of free will, and so presents a better research method for scientists to think about the paradox. When Joseph Polchinski proposed the paradox, he had Novikov’s Self-Consistency Principle in mind, which basically states that while time travel is possible, time paradoxes are forbidden.

However, a number of solutions have been formulated to avoid the inconsistencies Polchinski suggested, which essentially involves the billiard ball delivering a blow that changes its younger version’s course, but not enough to stop it from entering the wormhole. This solution is related to the ‘timeline-protection hypothesis’ which states that a probability distortion would occur in order to prevent a paradox from happening. This also helps explain why if you tried to time travel and murder your grandfather, something will always happen to make that impossible, thus preserving a consistent version of history.

- Books: Paradoxes of Time Travel by Ryan Wasserman is a wide-ranging exploration of time and time travel, including Polchinski’s Paradox.

Are Self-Fulfilling Prophecies Paradoxes?

A self-fulfilling prophecy is only a causality loop when the prophecy is truly known to happen and events in the future cause effects in the past, otherwise the phenomenon is not so much a paradox as a case of cause and effect. Say, for instance, an authority figure states that something is inevitable, proper, and true, convincing everyone through persuasive style. People, completely convinced through rhetoric, begin to behave as if the prediction were already true, and consequently bring it about through their actions. This might be seen best by an example where someone convincingly states:

“High-speed Magnetic Levitation Trains will dominate as the best form of transportation from the 21st Century onward.”

Jet travel, relying on diminishing fuel supplies, will be reserved for ocean crossing, and local flights will be a thing of the past. People now start planning on building networks of high-speed trains that run on electricity. Infrastructure gears up to supply the needed parts and the prediction becomes true not because it was truly inevitable (though it is a smart idea), but because people behaved as if it were true.

It even works on a smaller scale – the scale of individuals. The basic methodology for all those “self-help” books out in the world is that if you modify your thinking that you are successful (money, career, dating, etc.), then with the strengthening of that belief you start to behave like a successful person. People begin to notice and start to treat you like a successful person; it is a reinforcement/feedback loop and you actually become successful by behaving as if you were.

Are Time Paradoxes Inevitable?

The Butterfly Effect is a reference to Chaos Theory where seemingly trivial changes can have huge cascade reactions over long periods of time. Consequently, the Timeline corruption hypothesis states that time paradoxes are an unavoidable consequence of time travel, and even insignificant changes may be enough to alter history completely.

In one story, a paleontologist, with the help of a time travel device, travels back to the Jurassic Period to get photographs of Stegosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Allosaurus amongst other dinosaurs. He knows he can’t take samples so he just takes magnificent pictures from the fixed platform that is positioned precisely to not change anything about the environment. His assistant is about to pick a long blade of grass, but he stops him and explains how nothing must change because of their presence. They finish what they are doing and return to the present, but everything is gone. They reappear in a wild world with no humans and no signs that they ever existed. They fall to the floor of their platform, the only man-made thing in the whole world, and lament “Why? We didn’t change anything!” And there on the heel of the scientist’s shoe is a crushed butterfly.

The Butterfly Effect is also a movie, starring Ashton Kutcher as Evan Treborn and Amy Smart as Kayleigh Miller, where a troubled man has had blackouts during his youth, later explained by him traveling back into his own past and taking charge of his younger body briefly. The movie explores the issue of changing the timeline and how unintended consequences can propagate.

Scientists eager to avoid the paradoxes presented by time travel have come up with a number of ingenious ways in which to present a more consistent version of reality, some of which have been touched upon here, including:

- The Solution: time travel is impossible because of the very paradox it creates.

- Self-healing hypothesis: successfully altering events in the past will set off another set of events which will cause the present to remain the same.

- The Multiverse or “many-worlds” hypothesis: an alternate parallel universe or timeline is created each time an event is altered in the past.

- Erased timeline hypothesis : a person traveling to the past would exist in the new timeline, but have their own timeline erased.

Related Posts

© Copyright 2023 Astronomy Trek

Matador Original Series

10 key destinations for the historical time traveler.

Two hundred years ago a traveler had to wait months to traverse oceans. We now have the means to wake up in New York and fall asleep in Sydney, all in the same day.

The trend: travel is becoming exponentially more accessible to the common man.

But the tradeoff is that culture and history are being lost. Remote islanders maintain their outdated tribal customs merely to get a buck from the nearest walking wallet with a camera. Cities that in ancient times were considered quaint and romantic have become nothing more than identical concrete jungles.

We’re losing the remnants of human history with each passing day – why not find a means to time travel for leisure? Where would you go if you had a weekend in any city in any century?

1. Rome, Height of the Empire

No one in living memory has ever really seen the Colosseum. Whatever your religious beliefs, there used to be gods in that city; watching over the empire from their marbled countenance, and ensuring trade on one of the first greatest centers of business in the western world: the Roman Forum.

Imagine being able to walk down the epitome of civilization; they didn’t call the period after Christianity spread and the empire fell The Dark Ages for no good reason. ..

2. Kyoto, 16th Century

In the 1500’s, Kyoto served as the national capital and home to the imperial family. Tokyo (then Edo) was little more than a fishing village at this time, not yet placed on the map by the empowering of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

In modern times, many travelers journey to Kyoto to discover only remnants of what was once one of the most beautiful and mystical places on the planet. Back in its heyday, this Japanese city would have been the richest and most populated next to Osaka.

The predecessors to geisha gently walking in their kimonos, made from imported Chinese silk; visions of the mountains to the north and east not yet lost in a sea of grey; everything under ten meters high.

The only downside? Not much fresh fish or sushi: transporting the latest catch from Osaka to Kyoto took a while to perfect, and sushi was still in its infancy.

3. United States, The Old West

Back to the Future had the right idea – many people at one point imagine themselves as a cowboy or cowgirl.

What would you give to be riding on horseback on a cool summer morning in the undeveloped expanse of the western territories? Nothing for hundreds of miles in any direction, except perhaps the whistle of a steam locomotive and wandering tribes of Native Americans.

Of course, if you go back far enough in history, any land can be considered unexplored or undiscovered, but there’s a certain romantic connotation that stirs up when thinking about the American movement to the west.

It’s the promise of the unknown – traveling towards the Pacific, having uprooted everything stable, everything civilized in the east, and seeing where the Oregon Trail took you.

4. Ancient Egypt, c. 2500 BC

Watch the building of the pyramids and learn more about archaeoastronomy – skylights in the pyramids were carved so that certain constellations could be viewed at a set time of year.

Even the great structures themselves were arranged on the sand corresponding to the placement of three stars overhead. Discover the meaning of the Great Sphinx – who knows why it was built? Maybe some pharaoh just had a mutant pet.

Cairo will surely be hot and dry during this period in history, so remember to pack light loose-fitting clothing and plenty of sunscreen. If you wait around for another five hundred years, you might catch the finishing touches on Deir el Bahri .

5. London, 14th Century

“…the truth was that the modern world was invented in the Middle Ages. Everything from the legal system, to nation-states, to reliance on technology, to the concept of romantic love had first been established in medieval times.” – Timeline, Michael Crichton

Everyone wants to be a knight in shining armor or a princess fair and true. Chivalry isn’t dead. In fact, if you choose to travel to London roughly seven hundred years ago, you’ll find it quite alive and well.

A walking tour of this city will let you face the first real London Bridge, providing the only access across the Thames. Canterbury Tales by Chaucer paints a rather vivid picture of this era. Many of the buildings in London we associate with medieval times were already in place: The Tower of London, Westminster Hall, Westminster Abbey.

Remember to apply insect repellant liberally, as the Black Death was known to pass through Britain and France in this century.

6. Chang’an, Han Dynasty

The origin of The Silk Road and a golden age in Chinese history, when Confucian principles laid down the foundation for society and Buddhism was just beginning to spread. Travel west along this trade route and in a matter of months, you’ll reach the Roman Empire.

7. Chichen Itza, 5th century

Although you may not be in a temple of doom, it’s wise to heed the words of Indiana Jones and “protect your heart!” As one of the largest Mayan cities on the Yucatan Peninsula, Chichen Itza was the site of human sacrifices.

It’s true that quite a few of the largest temples are very well preserved in modern Mexico, but I challenge you to find another time or place in which ancient games that could rival basketball were played. Best to arrive before the Toltec siege.

8. India, c. 600 BC

The Buddha had about forty-five good years of teaching from the time of his reaching enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree to his death. Don’t waste them. Meeting the Awakened One and learning the dhamma firsthand would be an experience for which almost anyone in Asia would trade his or her life. Try and eliminate the suffering in your heart before your departure…

9. New York City, Roaring 20’s

By the time the 1920’s dawned in New York City, the modern version of a cityscape was already formed: Macy’s department stores, the public library, Grand Central Terminal, and the then world’s tallest Woolworth Building.

Unfortunately construction on the Empire State Building won’t commence until after the crash of ’29, but take advantage of this period in history with your choice of taxicabs or horse drawn carriages. Watch Lindbergh start his journey across the Atlantic. Gaze at the audience of women in hoop skirts and men in all too stiff and uncomfortable suits.

10. Babylon, c. 600 BC

One of the seven wonders of the ancient world: the hanging gardens of Babylon. As one of the first empires in human history, Babylon was built in the shadow of ancient Sumeria near the Euphrates River, and may have even been the source of the legendary Tower of Babel with its own Temple of Marduk.

I’m sure there are many asking “Why not see some dinosaurs?” Think a little practically in this impractical form of travel and question if you’d prefer camping in the late Cretaceous (and being trampled to death), or blending with the masses and observing the election of a Roman consul firsthand.

Besides, if a Tyrannosaur doesn’t get you, the meteor will later on.

Community Connection

You’ve been to the past, now meet travelers that we still remember tale. Read 10 Travelers and Why Their Tales Made History . Also, what other trends might we see in the future of travel? Check out 6 Predictions For the Future Of Travel .

Where and when would you go if you had a ticket guaranteeing a weekend of fun in any place at any time?

Trending Now

Inside italy's 'paradice music,' the all-ice, sub-zero concerts in a glacial igloo, traveling for a concert follow this expert checklist for a seamless trip, everything you need to know about concert cruises, eras tour stops where you can find the most affordable direct flights, how an international trip to see blink-182 led to disappointment, then redemption, discover matador, adventure travel, train travel, national parks, beaches and islands, ski and snow.

We use cookies for analytics tracking and advertising from our partners.

For more information read our privacy policy .

Matador's Newsletter

Subscribe for exclusive city guides, travel videos, trip giveaways and more!

You've been signed up!

Follow us on social media.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible, Researchers Say

Matthew S. Schwartz

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered. Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered.

"The past is obdurate," Stephen King wrote in his book about a man who goes back in time to prevent the Kennedy assassination. "It doesn't want to be changed."

Turns out, King might have been on to something.

Countless science fiction tales have explored the paradox of what would happen if you went back in time and did something in the past that endangered the future. Perhaps one of the most famous pop culture examples is in Back to the Future , when Marty McFly goes back in time and accidentally stops his parents from meeting, putting his own existence in jeopardy.

But maybe McFly wasn't in much danger after all. According a new paper from researchers at the University of Queensland, even if time travel were possible, the paradox couldn't actually exist.

Researchers ran the numbers and determined that even if you made a change in the past, the timeline would essentially self-correct, ensuring that whatever happened to send you back in time would still happen.

"Say you traveled in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus," University of Queensland scientist Fabio Costa told the university's news service .

"However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place," said Costa, who co-authored the paper with honors undergraduate student Germain Tobar.

"This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe."

A variation is known as the "grandfather paradox" — in which a time traveler kills their own grandfather, in the process preventing the time traveler's birth.

The logical paradox has given researchers a headache, in part because according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, "closed timelike curves" are possible, theoretically allowing an observer to travel back in time and interact with their past self — potentially endangering their own existence.

But these researchers say that such a paradox wouldn't necessarily exist, because events would adjust themselves.

Take the coronavirus patient zero example. "You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so, you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar told the university's news service.

In other words, a time traveler could make changes, but the original outcome would still find a way to happen — maybe not the same way it happened in the first timeline but close enough so that the time traveler would still exist and would still be motivated to go back in time.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you," Tobar said.

The paper, "Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice," was published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity . The findings seem consistent with another time travel study published this summer in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review Letters. That study found that changes made in the past won't drastically alter the future.

Bestselling science fiction author Blake Crouch, who has written extensively about time travel, said the new study seems to support what certain time travel tropes have posited all along.

"The universe is deterministic and attempts to alter Past Event X are destined to be the forces which bring Past Event X into being," Crouch told NPR via email. "So the future can affect the past. Or maybe time is just an illusion. But I guess it's cool that the math checks out."

- time travel

- grandfather paradox

Time travel is theoretically possible, calculations show. But that doesn't mean you could change the past.

- Time travel is possible based on the laws of physics, according to researchers.

- But time-travelers wouldn't be able to alter the past in a measurable way, they say.

- And the future would essentially stay the same, according to the reseachers.

Imagine you could hop into a time machine, press a button, and journey back to 2019, before the novel coronavirus made the leap from animals to humans.

What if you could find and isolate patient zero? Theoretically, the COVID-19 pandemic wouldn't happen, right?

Not quite, because then future-you wouldn't have decided to time travel in the first place.

For decades, physicists have been studying and debating versions of this paradox: If we could travel back in time and change the past, what would happen to the future?

A 2020 study offered a potential answer: Nothing.

"Events readjust around anything that could cause a paradox, so the paradox does not happen," Germain Tobar, the study's author previously told IFLScience .

Tobar's work, published in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity in September 2020, suggests that according to the rules of theoretical physics, anything you tried to change in the past would be corrected by subsequent events.

Put simply: It's theoretically possible to go back in time, but you couldn't change history.

The grandfather paradox

Physicists have considered time travel to be theoretically possible since Albert Einstein came up with his theory of relativity. Einstein's calculations suggest it's possible for an object in our universe to travel through space and time in a circular direction, eventually ending up at a point on its journey where it's been before – a path called a closed time-like curve.

Related stories

Still, physicists continue to struggle with scenarios like the coronavirus example above, in which time-travelers alter events that already happened. The most famous example is known as the grandfather paradox: Say a time-traveler goes back to the past and kills a younger version of his or her grandfather. The grandfather then wouldn't have any children, erasing the time-traveler's parents and, of course, the time-traveler, too. But then who would kill Grandpa?

A take on this paradox appears in the movie "Back to the Future," when Marty McFly almost stops his parents from meeting in the past – potentially causing himself to disappear.

To address the paradox, Tobar and his supervisor, Dr. Fabio Costa, used the "billiard-ball model," which imagines cause and effect as a series of colliding billiard balls, and a circular pool table as a closed time-like curve.

Imagine a bunch of billiard balls laid out across that circular table. If you push one ball from position X, it bangs around the table, hitting others in a particular pattern.

The researchers calculated that even if you mess with the ball's pattern at some point in its journey, future interactions with other balls can correct its path, leading it to come back to the same position and speed that it would have had you not interfered.

"Regardless of the choice, the ball will fall into the same place," Dr Yasunori Nomura, a theoretical physicist at UC Berkeley, previously told Insider.

Tobar's model, in other words, says you could travel back in time, but you couldn't change how events unfolded significantly enough to alter the future, Nomura said. Applied to the grandfather paradox, then, this would mean that something would always get in the way of your attempt to kill your grandfather. Or at least by the time he did die, your grandmother would already be pregnant with your mother.

Back to the coronavirus example. Let's say you were to travel back to 2019 and intervene in patient zero's life. According to Tobar's line of thinking, the pandemic would still happen somehow.

"You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar said, according to Australia's University of Queensland , where Tobar graduated from.

Nomura said that although the model is too simple to represent the full range of cause and effect in our universe, it's a good starting point for future physicists.

Watch: There are 2 types of time travel and physicists agree that one of them is possible

- Main content

- Texas Brazos Trail Region

- Texas Forest Trail Region

- Texas Forts Trail Region

- Texas Hill Country Trail Region

- Texas Independence Trail Region

- Texas Lakes Trail Region

- Texas Mountain Trail Region

- Texas Pecos Trail Region

- Texas Plains Trail Region

- Texas Tropical Trail Region

- African American Heritage

- American Indian Heritage

- Asian Heritage

- European Heritage

- German Heritage

- Hispanic Heritage

- State Historic Sites

- Arts and Culture

- Courthouses

- Cowboy Culture

- Historic Businesses

- Historic Downtowns

- Historic Trails And Highways

- National Monuments and Landmarks

- Presidential History

- Sacred Places

- Scenic Drives

- Travel Newsletter

- Historic Overnights: Mason

- Historic Overnights: Galveston Island

- Mobile Tours

- Printable Guides

- Themed Excursions

- Roadside Heritage

- Submit Your Event

- Norwegian Country Christmas Tour

- Texas Route 66 Festival

Events Calendar

What will you do on your next trip? Texas has several fun upcoming festivals and events to add to your experience. Search by date, type of event, location or keyword below.

Find Experiences

- Arts / Culture

- Family-Friendly

- History / Heritage

- Live Performance

- Arts & Crafts

Brazos Trail Region

- Forest Trail Region

Forts Trail Region

Hill Country Trail Region

- Independence Trail Region

Lakes Trail Region

Mountain Trail Region

- Pecos Trail Region

Plains Trail Region

Tropical Trail Region

MUMENTOUS: Football, Glue Guns, Moms, and a Super-Sized Tradition Born Deep in the Heart of Texas

200 North 5th Street Garland, TX 75040 (888) 879-0264 Website

MUMENTOUS: Football, Glue Guns, Moms, and a Super-Sized Tradition Born Deep in the Heart of Texas 200 North 5th Street Garland, TX 75040

Qunah Parker Exhibit: One Man, Two Worlds

Barnard's Mill and Art Museum 307 SW Barnard Street Glen Rose, TX 76048 (972) 965-4455 Website

Qunah Parker Exhibit: One Man, Two Worlds Barnard's Mill and Art Museum 307 SW Barnard Street Glen Rose, TX 76048

101st Annual Motley-Dickens Old Settlers Reunion & Rodeo

896 3rd Street Roaring Springs, TX 79256 (806) 231-0495

101st Annual Motley-Dickens Old Settlers Reunion & Rodeo 896 3rd Street Roaring Springs, TX 79256

A Day at the Farm and Farmers Market

33 Herff Farm Boerne, TX 78006 (830) 249-4616 Website

A Day at the Farm and Farmers Market 33 Herff Farm Boerne, TX 78006

Dinosaurs Live!

1 Nature Place McKinney, TX 75069 (972) 562-5566 Website

Dinosaurs Live! 1 Nature Place McKinney, TX 75069

Grand Prairie Farmers Market

120 W. Main Street Grand Prairie, TX 75050 (972) 237-4798 Website

Grand Prairie Farmers Market 120 W. Main Street Grand Prairie, TX 75050

Yoga in the Courtyard

508 E. Austin St Fredericksburg, TX 78624 (830) 997-8600 Website

Yoga in the Courtyard 508 E. Austin St Fredericksburg, TX 78624

Lantern-lit Coper Mine Tour

Franklin Mountains State Park - 2900 Tom Mays Park Access Rd. El Paso, TX 79911 (915) 444-9100 Website

Lantern-lit Coper Mine Tour Franklin Mountains State Park - 2900 Tom Mays Park Access Rd. El Paso, TX 79911

Prospect Mine Tour

Prospect Mine Tour Franklin Mountains State Park - 2900 Tom Mays Park Access Rd. El Paso, TX 79911

Ancient Landscapes of South Texas, Hiding in Plain Sight

317 E. Railroad Ave. Port Isabel, TX 78578 (956) 374-9003 Website

Ancient Landscapes of South Texas, Hiding in Plain Sight 317 E. Railroad Ave. Port Isabel, TX 78578

Adulti-Verse (21+) at Meow Wolf Grapevine

3000 Grapevine Mills Pkwy Suite 253 Grapevine, TX 76051 (682) 345-8832 Website

Adulti-Verse (21+) at Meow Wolf Grapevine 3000 Grapevine Mills Pkwy Suite 253 Grapevine, TX 76051

Vereins Quilt Guild Quilt Show

1407 E. Main St. Fredericksburg , TX 78624 (361) 676-2293

Vereins Quilt Guild Quilt Show 1407 E. Main St. Fredericksburg , TX 78624

Grapevine Main LIVE!

815 S. Main St. Grapevine, TX 76051 (817) 410-3185 Website

Grapevine Main LIVE! 815 S. Main St. Grapevine, TX 76051

Water Lantern Festival

Haggard Park W Chaparral St Amarillo, TX 79107 (435) 554-0134 Website

Water Lantern Festival Haggard Park W Chaparral St Amarillo, TX 79107

Dinosaurs Live! Life-size Animatronic Dinosaurs Returns

Dinosaurs Live! Life-size Animatronic Dinosaurs Returns 1 Nature Place McKinney, TX 75069

Blues on Main

101 North West Main Street Ennis, TX 75119 (214) 475-0042 Website

Blues on Main 101 North West Main Street Ennis, TX 75119

Ennis Pumpkin Patch & Hay Maze

111 NW Main St Ennis, TX 75119 (972) 878-4748 Website

Ennis Pumpkin Patch & Hay Maze 111 NW Main St Ennis, TX 75119

Ennis Autumn Daze

Ennis Autumn Daze 111 NW Main St Ennis, TX 75119

2nd Annual Texas Banana Pudding Festival

Slaton Bakery 109 S. 9th St. Slaton, Texas 79364 (806) 828-3253 Website

2nd Annual Texas Banana Pudding Festival Slaton Bakery 109 S. 9th St. Slaton, Texas 79364

Texas Forts Trail Caravan Part 3

Brownwood Event Center 601 E Baker Street Brownwood, Texas 76801 (800) 484-1462 Website

Texas Forts Trail Caravan Part 3 Brownwood Event Center Complex 601 E Baker Street Brownwood, Texas 76801

Lubbock’s First Friday Art Trail

Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts 511 Ave. K Lubbock, Texas 79401 (806) 762-8606 Website

Lubbock's First Friday Art Trail Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts 511 Ave. K Lubbock, Texas 79401

ItalianCarFest

626 Ball St. Grapevine, TX 76051 (817) 410-3185 Website

ItalianCarFest 626 Ball St. Grapevine, TX 76051

Vinyl Radio

112 West 6th Ave Corsicana, TX 75110 (903) 874-7792 Website

Vinyl Radio 112 West 6th Ave Corsicana, TX 75110

60th Anniversary of the Gilligan’s Island Fundraiser

209 N Broadway St, Brownwood, TX 76801 Brownwood, TX 76801 (325) 641-1926 Website

60th Anniversary of the Gilligan’s Island Fundraiser 209 N Broadway St, Brownwood, TX 76801 Brownwood, TX 76801

Guided Trails

Heard Natural Science Museum and Wildlife Sanctuary 1 Nature Place McKinney, TX 75069 (972) 562-5566 Website

Guided Trails Heard Natural Science Museum and Wildlife Sanctuary 1 Nature Place McKinney, TX 75069

All the Bells and Whistles: The History and Heritage of Homecoming Mums in Texas

Garland City Hall, 200 N. Fifth Street Garland, TX 75040 (972) 205-2749 Website

All the Bells and Whistles: The History and Heritage of Homecoming Mums in Texas Garland City Hall, 200 N. Fifth Street Garland, TX 75040

Jurassic Night Out

Jurassic Night Out Heard Natural Science Museum and Wildlife Sanctuary 1 Nature Place McKinney, TX 75069

A Wrinkle in Time

119 W. 6th Ave Corsicana, TX 75110 903-872-5421 Website

A Wrinkle in Time 119 W. 6th Ave Corsicana, TX 75110

38th Annual GrapeFest — A Texas Wine Experience

636 S. Main St Grapevine, TX 76051 (817) 410-3185 Website

38th Annual GrapeFest - A Texas Wine Experience 636 S. Main St Grapevine, TX 76051

38th Annual GrapeFest

38th Annual GrapeFest 636 S. Main St Grapevine, TX 76051

Exhibition Opening; Target Texas: Studio Practice

1902 North Shoreline Boulevard Corpus Christi, TX 78401 (361) 825-3500 Website

Exhibition Opening; Target Texas: Studio Practice 1902 North Shoreline Boulevard Corpus Christi, TX 78401

Quanah Parker Day 2024

TAKE A STAND WITH AN ARROW TO HONOR QUANAH PARKER WHAT: Quanah Parker Day in the Texas Plains Trail Region WHEN: Sat., Sept 14, 2024 WHERE: Communities with Quanah Parker Trail giant arrow markers TEXAS PLAINS TRAIL REGION — Quanah Parker Trail arrows will stand a little taller on Saturday, Sept. 14 - Quanah Parker Day in Texas. The statewide observance, which Texas Governor Greg Abbott decreed for the second Saturday of each September, commemorates the life of Comanche Chief Quanah Parker. In the Texas Plains Trail Region, one of the ten regions designated as part of the Texas Heritage Trails Program of the Texas Historical Commission, volunteer leaders launched a Quanah Parker Trail project in 2010, which has organized some regional events and avenues for participating in the statewide recognition. About the Quanah Parker Trail Every Texas student passing through 4th and 7th grade by now has learned the story of Quanah Parker; his mother Cynthia Ann Parker, who was kidnapped as a child and raised among the Comanches; and their lives as Texas Indians. The Comanches were called “Lords of the Southern Plains” owing to their superb horsemanship and prowess in hunting bison from horseback. In the Texas Plains Trail Region (TPTR), we encourage you to honor Quanah Parker Day by paying a visit to a nearby steel arrow sculpture that marks a county’s inclusion on the Quanah Parker Trail (QPT). Take a stand with Quanah Parker and the arrow. Share your photos with us on social media and be sure to tell your family and friends about your adventure. The QPT placed within the TPTR is conceptual in nature. Counties of the TPTR installed 88 steel arrows created by sculptor welder Charles A. Smith (1943–2018), to commemorate their inclusion in the Comanchería, the territorial range of the Comanches in the 19th century. The trail is named for Quanah Parker, as he is considered as the most renowned Indian leader who frequented this area. The heart of the story is this: Every county’s land within TPTR was once part of the territory of the Comanches, known as the Comanchería. What local communities can do to honor Quanah’s legacy The site where QPT Arrows are installed can be cleared of tall growth that may obscure them from view. Weathered arrows can be touched up with paint made for metal tractors and available at local farm and feed stores, or hardware stores. Streamers of red, yellow and blue, the colors of the shield for the logo of the Comanche Nation, can be tied onto the arrows to flutter in the wind and draw the attention of travelers to the history of the region. More about Quanah Parker and the Comanches And the other part of the story this: At one time or another, Quanah crossed the lands where we live now. As a warrior, Quanah rode with the Kwahada division of the Comanche tribe. The Kwahada made their home on the southern High Plains of the Llano Estacado and as well traversed the Rolling Plains of Texas in the late 19th century. Under Quanah’s leadership, the Kwahada remained the last Comanche holdouts who resisted the U.S. military's effort to force all Indians to move onto reservations. After the Comanches moved to the reservation in Indian Territory by the end of 1875, Quanah continued as a leader, helping them adjust to a different way of life. He was appointed as a Comanche chief by Indian agents of the federal government. Quanah coordinated cultural and political activities felt to be necessary to aid the Comanche people in adapting to the challenges of modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In this capacity, he continued to travel throughout our region, by mule-drawn wagon, touring car, and train. He became a celebrity, and as a much sought-after representative of frontier history, in the TPTR alone he attended a funeral in Dalhart, addressed a crowd in Matador, attended a celebration in the town of Quanah named for him, and visited ranchers Samuel Burk Burnett in Guthrie and Charles Goodnight near Claude. For more information • About the Quanah Parker Trail in the TPTR, visit: www.quanahparkertrail.com Biographies of Quanah • Bill Neeley, “The Last Comanche Chief: The Life and Times of Quanah Parker” (J. Wiley, 1996). • William T. Hagan, “Quanah Parker, Comanche Chief” (University of Oklahoma Press, 1993). History about his mother, Cynthia Ann Parker • Paul Carlson and Tom Crum, “ Myth, Memory, and Massacre: The Pease River Capture of Cynthia Ann Parker ” (Texas Tech University Press, 2010). • Jack K. Selden, “ Return: The Parker Story ” (Clacton Press, 2006). History of the Comanches • Pekka Hämäläinen, “The Comanche Empire” (Yale University Press, 2009). • Ernest Wallace and E. Adamson Hoebel, “Comanches, Lords of the South Plains”(University of Oklahoma Press, 1952).

Quanah Parker Day 2024

Living History

7200 Paredes Line Road Brownsville, TX 78526 (956) 541-2785 Website

Living History 7200 Paredes Line Road Brownsville, TX 78526

Mimosas at the Market

Beaton St Corsicana, TX 75110 (903) 654-4852 Website

Mimosas at the Market Beaton St Corsicana, TX 75110

39th Annual Kolache Festival

Downtown on the Square in Caldwell, Texas Caldwell, TX 77836 (979) 567-0000 Website

39th Annual Kolache Festival Downtown on the Square in Caldwell, Texas Caldwell, TX 77836

Results 1 - 48 of 281

Submit Your Event

We only use cookies that are necessary for this site to function to provide you with the best experience. Learn More

Quick Search

Location map, e-newsletter.

Sign up for the Texas Heritage Traveler—your quarterly Texas travel inspiration.

Is Time Travel Possible?

We all travel in time! We travel one year in time between birthdays, for example. And we are all traveling in time at approximately the same speed: 1 second per second.

We typically experience time at one second per second. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

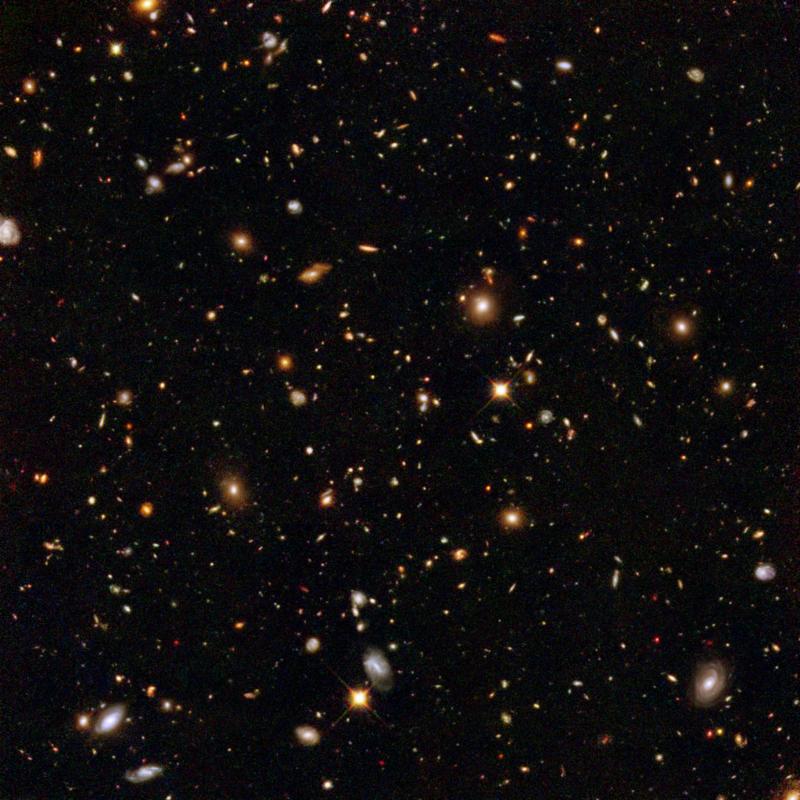

NASA's space telescopes also give us a way to look back in time. Telescopes help us see stars and galaxies that are very far away . It takes a long time for the light from faraway galaxies to reach us. So, when we look into the sky with a telescope, we are seeing what those stars and galaxies looked like a very long time ago.

However, when we think of the phrase "time travel," we are usually thinking of traveling faster than 1 second per second. That kind of time travel sounds like something you'd only see in movies or science fiction books. Could it be real? Science says yes!

This image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows galaxies that are very far away as they existed a very long time ago. Credit: NASA, ESA and R. Thompson (Univ. Arizona)

How do we know that time travel is possible?

More than 100 years ago, a famous scientist named Albert Einstein came up with an idea about how time works. He called it relativity. This theory says that time and space are linked together. Einstein also said our universe has a speed limit: nothing can travel faster than the speed of light (186,000 miles per second).

Einstein's theory of relativity says that space and time are linked together. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

What does this mean for time travel? Well, according to this theory, the faster you travel, the slower you experience time. Scientists have done some experiments to show that this is true.

For example, there was an experiment that used two clocks set to the exact same time. One clock stayed on Earth, while the other flew in an airplane (going in the same direction Earth rotates).

After the airplane flew around the world, scientists compared the two clocks. The clock on the fast-moving airplane was slightly behind the clock on the ground. So, the clock on the airplane was traveling slightly slower in time than 1 second per second.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Can we use time travel in everyday life?

We can't use a time machine to travel hundreds of years into the past or future. That kind of time travel only happens in books and movies. But the math of time travel does affect the things we use every day.

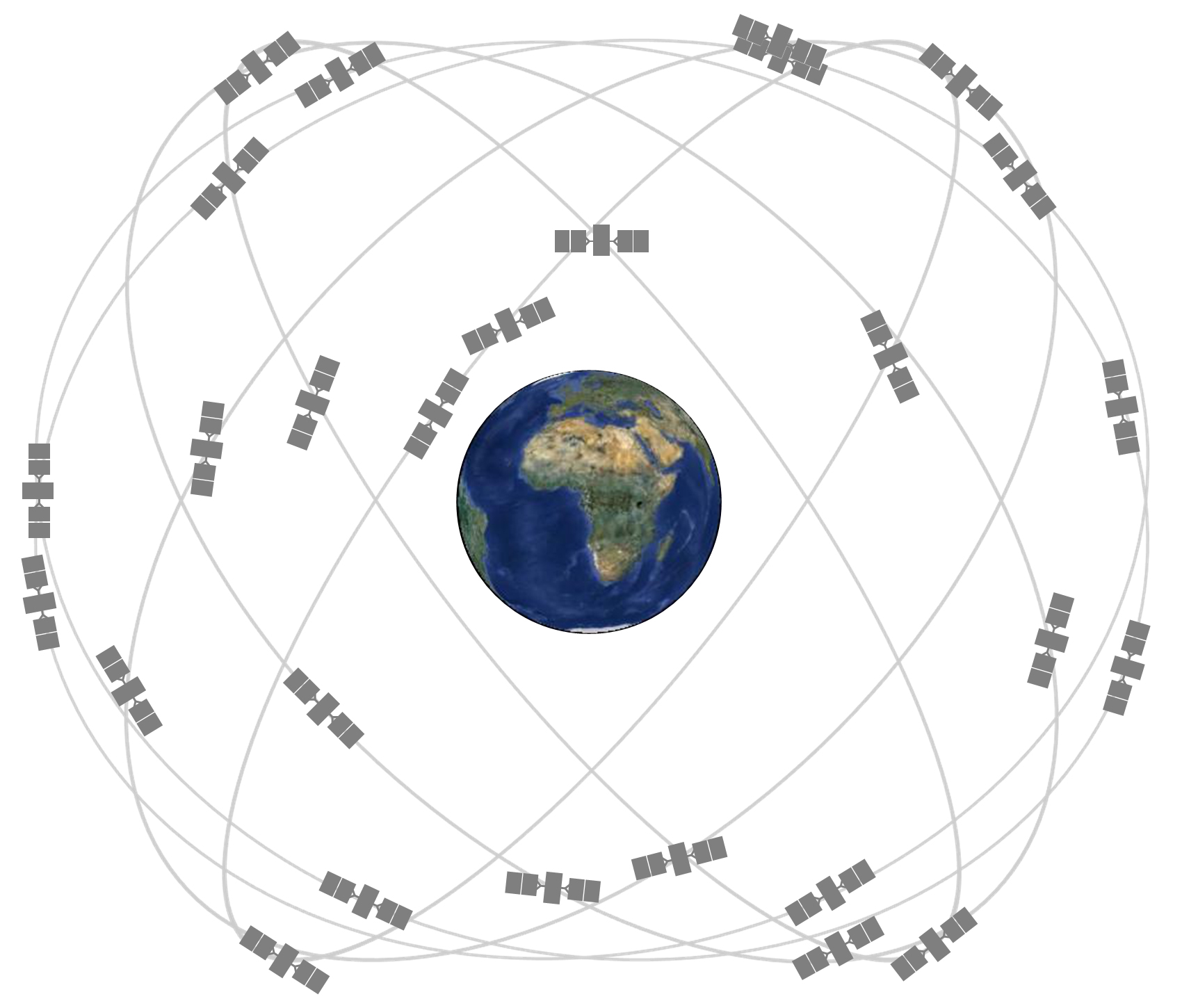

For example, we use GPS satellites to help us figure out how to get to new places. (Check out our video about how GPS satellites work .) NASA scientists also use a high-accuracy version of GPS to keep track of where satellites are in space. But did you know that GPS relies on time-travel calculations to help you get around town?

GPS satellites orbit around Earth very quickly at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. This slows down GPS satellite clocks by a small fraction of a second (similar to the airplane example above).

GPS satellites orbit around Earth at about 8,700 miles (14,000 kilometers) per hour. Credit: GPS.gov

However, the satellites are also orbiting Earth about 12,550 miles (20,200 km) above the surface. This actually speeds up GPS satellite clocks by a slighter larger fraction of a second.

Here's how: Einstein's theory also says that gravity curves space and time, causing the passage of time to slow down. High up where the satellites orbit, Earth's gravity is much weaker. This causes the clocks on GPS satellites to run faster than clocks on the ground.

The combined result is that the clocks on GPS satellites experience time at a rate slightly faster than 1 second per second. Luckily, scientists can use math to correct these differences in time.

If scientists didn't correct the GPS clocks, there would be big problems. GPS satellites wouldn't be able to correctly calculate their position or yours. The errors would add up to a few miles each day, which is a big deal. GPS maps might think your home is nowhere near where it actually is!

In Summary:

Yes, time travel is indeed a real thing. But it's not quite what you've probably seen in the movies. Under certain conditions, it is possible to experience time passing at a different rate than 1 second per second. And there are important reasons why we need to understand this real-world form of time travel.

If you liked this, you may like:

Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Emeritus professor, Physics, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Peter Watson received funding from NSERC. He is affiliated with Carleton University and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicists.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Time travel makes regular appearances in popular culture, with innumerable time travel storylines in movies, television and literature. But it is a surprisingly old idea: one can argue that the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex , written by Sophocles over 2,500 years ago, is the first time travel story .

But is time travel in fact possible? Given the popularity of the concept, this is a legitimate question. As a theoretical physicist, I find that there are several possible answers to this question, not all of which are contradictory.

The simplest answer is that time travel cannot be possible because if it was, we would already be doing it. One can argue that it is forbidden by the laws of physics, like the second law of thermodynamics or relativity . There are also technical challenges: it might be possible but would involve vast amounts of energy.

There is also the matter of time-travel paradoxes; we can — hypothetically — resolve these if free will is an illusion, if many worlds exist or if the past can only be witnessed but not experienced. Perhaps time travel is impossible simply because time must flow in a linear manner and we have no control over it, or perhaps time is an illusion and time travel is irrelevant.

Laws of physics

Since Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity — which describes the nature of time, space and gravity — is our most profound theory of time, we would like to think that time travel is forbidden by relativity. Unfortunately, one of his colleagues from the Institute for Advanced Study, Kurt Gödel, invented a universe in which time travel was not just possible, but the past and future were inextricably tangled.

We can actually design time machines , but most of these (in principle) successful proposals require negative energy , or negative mass, which does not seem to exist in our universe. If you drop a tennis ball of negative mass, it will fall upwards. This argument is rather unsatisfactory, since it explains why we cannot time travel in practice only by involving another idea — that of negative energy or mass — that we do not really understand.

Mathematical physicist Frank Tipler conceptualized a time machine that does not involve negative mass, but requires more energy than exists in the universe .

Time travel also violates the second law of thermodynamics , which states that entropy or randomness must always increase. Time can only move in one direction — in other words, you cannot unscramble an egg. More specifically, by travelling into the past we are going from now (a high entropy state) into the past, which must have lower entropy.

This argument originated with the English cosmologist Arthur Eddington , and is at best incomplete. Perhaps it stops you travelling into the past, but it says nothing about time travel into the future. In practice, it is just as hard for me to travel to next Thursday as it is to travel to last Thursday.

Resolving paradoxes

There is no doubt that if we could time travel freely, we run into the paradoxes. The best known is the “ grandfather paradox ”: one could hypothetically use a time machine to travel to the past and murder their grandfather before their father’s conception, thereby eliminating the possibility of their own birth. Logically, you cannot both exist and not exist.

Read more: Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five , published in 1969, describes how to evade the grandfather paradox. If free will simply does not exist, it is not possible to kill one’s grandfather in the past, since he was not killed in the past. The novel’s protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, can only travel to other points on his world line (the timeline he exists in), but not to any other point in space-time, so he could not even contemplate killing his grandfather.

The universe in Slaughterhouse-Five is consistent with everything we know. The second law of thermodynamics works perfectly well within it and there is no conflict with relativity. But it is inconsistent with some things we believe in, like free will — you can observe the past, like watching a movie, but you cannot interfere with the actions of people in it.

Could we allow for actual modifications of the past, so that we could go back and murder our grandfather — or Hitler ? There are several multiverse theories that suppose that there are many timelines for different universes. This is also an old idea: in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol , Ebeneezer Scrooge experiences two alternative timelines, one of which leads to a shameful death and the other to happiness.

Time is a river

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote that:

“ Time is like a river made up of the events which happen , and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.”

We can imagine that time does flow past every point in the universe, like a river around a rock. But it is difficult to make the idea precise. A flow is a rate of change — the flow of a river is the amount of water that passes a specific length in a given time. Hence if time is a flow, it is at the rate of one second per second, which is not a very useful insight.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking suggested that a “ chronology protection conjecture ” must exist, an as-yet-unknown physical principle that forbids time travel. Hawking’s concept originates from the idea that we cannot know what goes on inside a black hole, because we cannot get information out of it. But this argument is redundant: we cannot time travel because we cannot time travel!

Researchers are investigating a more fundamental theory, where time and space “emerge” from something else. This is referred to as quantum gravity , but unfortunately it does not exist yet.

So is time travel possible? Probably not, but we don’t know for sure!

- Time travel

- Stephen Hawking

- Albert Einstein

- Listen to this article

- Time travel paradox

- Arthur Eddington

Head of Evidence to Action

Supply Chain - Assistant/Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Education Research Fellow

OzGrav Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

Is time travel even possible? An astrophysicist explains the science behind the science fiction

Published: Nov 13, 2023

By: Magazine Editor

Written by Adi Foord , assistant professor of physics , UMBC

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to [email protected] .

Will it ever be possible for time travel to occur? – Alana C., age 12, Queens, New York

Have you ever dreamed of traveling through time, like characters do in science fiction movies? For centuries, the concept of time travel has captivated people’s imaginations. Time travel is the concept of moving between different points in time, just like you move between different places. In movies, you might have seen characters using special machines, magical devices or even hopping into a futuristic car to travel backward or forward in time.

But is this just a fun idea for movies, or could it really happen?

The question of whether time is reversible remains one of the biggest unresolved questions in science. If the universe follows the laws of thermodynamics , it may not be possible. The second law of thermodynamics states that things in the universe can either remain the same or become more disordered over time.

It’s a bit like saying you can’t unscramble eggs once they’ve been cooked. According to this law, the universe can never go back exactly to how it was before. Time can only go forward, like a one-way street.

Time is relative

However, physicist Albert Einstein’s theory of special relativity suggests that time passes at different rates for different people. Someone speeding along on a spaceship moving close to the speed of light – 671 million miles per hour! – will experience time slower than a person on Earth.

People have yet to build spaceships that can move at speeds anywhere near as fast as light, but astronauts who visit the International Space Station orbit around the Earth at speeds close to 17,500 mph. Astronaut Scott Kelly has spent 520 days at the International Space Station, and as a result has aged a little more slowly than his twin brother – and fellow astronaut – Mark Kelly. Scott used to be 6 minutes younger than his twin brother. Now, because Scott was traveling so much faster than Mark and for so many days, he is 6 minutes and 5 milliseconds younger .

Some scientists are exploring other ideas that could theoretically allow time travel. One concept involves wormholes , or hypothetical tunnels in space that could create shortcuts for journeys across the universe. If someone could build a wormhole and then figure out a way to move one end at close to the speed of light – like the hypothetical spaceship mentioned above – the moving end would age more slowly than the stationary end. Someone who entered the moving end and exited the wormhole through the stationary end would come out in their past.

However, wormholes remain theoretical: Scientists have yet to spot one. It also looks like it would be incredibly challenging to send humans through a wormhole space tunnel.

Paradoxes and failed dinner parties

There are also paradoxes associated with time travel. The famous “ grandfather paradox ” is a hypothetical problem that could arise if someone traveled back in time and accidentally prevented their grandparents from meeting. This would create a paradox where you were never born, which raises the question: How could you have traveled back in time in the first place? It’s a mind-boggling puzzle that adds to the mystery of time travel.

Famously, physicist Stephen Hawking tested the possibility of time travel by throwing a dinner party where invitations noting the date, time and coordinates were not sent out until after it had happened. His hope was that his invitation would be read by someone living in the future, who had capabilities to travel back in time. But no one showed up.

As he pointed out : “The best evidence we have that time travel is not possible, and never will be, is that we have not been invaded by hordes of tourists from the future.”

Telescopes are time machines

Interestingly, astrophysicists armed with powerful telescopes possess a unique form of time travel. As they peer into the vast expanse of the cosmos, they gaze into the past universe. Light from all galaxies and stars takes time to travel, and these beams of light carry information from the distant past. When astrophysicists observe a star or a galaxy through a telescope, they are not seeing it as it is in the present, but as it existed when the light began its journey to Earth millions to billions of years ago. https://www.youtube.com/embed/QeRtcJi3V38?wmode=transparent&start=0 Telescopes are a kind of time machine – they let you peer into the past.

NASA’s newest space telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope , is peering at galaxies that were formed at the very beginning of the Big Bang, about 13.7 billion years ago.

While we aren’t likely to have time machines like the ones in movies anytime soon, scientists are actively researching and exploring new ideas. But for now, we’ll have to enjoy the idea of time travel in our favorite books, movies and dreams.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article and see more than 250 UMBC articles available in The Conversation.

Tags: CNMS , Physics , The Conversation

Related Posts

- Campus Life

Inspired by evolutionary biology ‘aha’ moment, Nhi Nguyen ’25 takes action to help children grasp their own worth

- Science & Tech

27th Summer Undergraduate Research Fest prepares students for scholarly next steps

Liz Willman ’25 uses internships to make childhood vet dreams a reality

Search UMBC Search

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Equal Opportunity

- Privacy PDF Download

- Web Accessibility

Search UMBC.edu

- Newsletters

Time travel: five ways that we could do it

Cathal O’Connell

Cathal O'Connell is a science writer based in Melbourne.

In 2009 the British physicist Stephen Hawking held a party for time travellers – the twist was he sent out the invites a year later (No guests showed up). Time travel is probably impossible. Even if it were possible, Hawking and others have argued that you could never travel back before the moment your time machine was built.

But travel to the future? That’s a different story.

Of course, we are all time travellers as we are swept along in the current of time, from past to future, at a rate of one hour per hour.

But, as with a river, the current flows at different speeds in different places. Science as we know it allows for several methods to take the fast-track into the future. Here’s a rundown.

1. Time travel via speed

This is the easiest and most practical way to time travel into the far future – go really fast.

According to Einstein’s theory of special relativity, when you travel at speeds approaching the speed of light, time slows down for you relative to the outside world.

This is not a just a conjecture or thought experiment – it’s been measured. Using twin atomic clocks (one flown in a jet aircraft, the other stationary on Earth) physicists have shown that a flying clock ticks slower, because of its speed.

In the case of the aircraft, the effect is minuscule. But If you were in a spaceship travelling at 90% of the speed of light, you’d experience time passing about 2.6 times slower than it was back on Earth.

And the closer you get to the speed of light, the more extreme the time-travel.

Computer solves a major time travel problem

The highest speeds achieved through any human technology are probably the protons whizzing around the Large Hadron Collider at 99.9999991% of the speed of light. Using special relativity we can calculate one second for the proton is equivalent to 27,777,778 seconds, or about 11 months , for us.

Amazingly, particle physicists have to take this time dilation into account when they are dealing with particles that decay. In the lab, muon particles typically decay in 2.2 microseconds. But fast moving muons, such as those created when cosmic rays strike the upper atmosphere, take 10 times longer to disintegrate.

2. Time travel via gravity

The next method of time travel is also inspired by Einstein. According to his theory of general relativity, the stronger the gravity you feel, the slower time moves.

As you get closer to the centre of the Earth, for example, the strength of gravity increases. Time runs slower for your feet than your head.

Again, this effect has been measured. In 2010, physicists at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) placed two atomic clocks on shelves, one 33 centimetres above the other, and measured the difference in their rate of ticking. The lower one ticked slower because it feels a slightly stronger gravity.

To travel to the far future, all we need is a region of extremely strong gravity, such as a black hole. The closer you get to the event horizon, the slower time moves – but it’s risky business, cross the boundary and you can never escape.

And anyway, the effect is not that strong so it’s probably not worth the trip.

Assuming you had the technology to travel the vast distances to reach a black hole (the nearest is about 3,000 light years away), the time dilation through travelling would be far greater than any time dilation through orbiting the black hole itself.

(The situation described in the movie Interstellar , where one hour on a planet near a black hole is the equivalent of seven years back on Earth, is so extreme as to be impossible in our Universe, according to Kip Thorne, the movie’s scientific advisor.)

The most mindblowing thing, perhaps, is that GPS systems have to account for time dilation effects (due to both the speed of the satellites and gravity they feel) in order to work. Without these corrections, your phones GPS capability wouldn’t be able to pinpoint your location on Earth to within even a few kilometres.

3. Time travel via suspended animation

Another way to time travel to the future may be to slow your perception of time by slowing down, or stopping, your bodily processes and then restarting them later.

Bacterial spores can live for millions of years in a state of suspended animation, until the right conditions of temperature, moisture, food kick start their metabolisms again. Some mammals, such as bears and squirrels, can slow down their metabolism during hibernation, dramatically reducing their cells’ requirement for food and oxygen.

Could humans ever do the same?

Though completely stopping your metabolism is probably far beyond our current technology, some scientists are working towards achieving inducing a short-term hibernation state lasting at least a few hours. This might be just enough time to get a person through a medical emergency, such as a cardiac arrest, before they can reach the hospital.

In 2005, American scientists demonstrated a way to slow the metabolism of mice (which do not hibernate) by exposing them to minute doses of hydrogen sulphide, which binds to the same cell receptors as oxygen. The core body temperature of the mice dropped to 13 °C and metabolism decreased 10-fold. After six hours the mice could be reanimated without ill effects.

Unfortunately, similar experiments on sheep and pigs were not successful, suggesting the method might not work for larger animals.

Another method, which induces a hypothermic hibernation by replacing the blood with a cold saline solution, has worked on pigs and is currently undergoing human clinical trials in Pittsburgh.

4. Time travel via wormholes

General relativity also allows for the possibility for shortcuts through spacetime, known as wormholes, which might be able to bridge distances of a billion light years or more, or different points in time.

Many physicists, including Stephen Hawking, believe wormholes are constantly popping in and out of existence at the quantum scale, far smaller than atoms. The trick would be to capture one, and inflate it to human scales – a feat that would require a huge amount of energy, but which might just be possible, in theory.

Attempts to prove this either way have failed, ultimately because of the incompatibility between general relativity and quantum mechanics.

5. Time travel using light

Another time travel idea, put forward by the American physicist Ron Mallet, is to use a rotating cylinder of light to twist spacetime. Anything dropped inside the swirling cylinder could theoretically be dragged around in space and in time, in a similar way to how a bubble runs around on top your coffee after you swirl it with a spoon.

According to Mallet, the right geometry could lead to time travel into either the past and the future.

Since publishing his theory in 2000, Mallet has been trying to raise the funds to pay for a proof of concept experiment, which involves dropping neutrons through a circular arrangement of spinning lasers.

His ideas have not grabbed the rest of the physics community however, with others arguing that one of the assumptions of his basic model is plagued by a singularity, which is physics-speak for “it’s impossible”.

The Royal Institution of Australia has an Education resource based on this article. You can access it here .

Related Reading: Computer solves a major time travel problem

Originally published by Cosmos as Time travel: five ways that we could do it

Please login to favourite this article.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Time Travel

There is an extensive literature on time travel in both philosophy and physics. Part of the great interest of the topic stems from the fact that reasons have been given both for thinking that time travel is physically possible—and for thinking that it is logically impossible! This entry deals primarily with philosophical issues; issues related to the physics of time travel are covered in the separate entries on time travel and modern physics and time machines . We begin with the definitional question: what is time travel? We then turn to the major objection to the possibility of backwards time travel: the Grandfather paradox. Next, issues concerning causation are discussed—and then, issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We end with a discussion of the question why, if backwards time travel will ever occur, we have not been visited by time travellers from the future.

1.1 Time Discrepancy

1.2 changing the past, 2.1 can and cannot, 2.2 improbable coincidences, 2.3 inexplicable occurrences, 3.1 backwards causation, 3.2 causal loops, 4.1 time travel and time, 4.2 time travel and change, 5. where are the time travellers, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is time travel.

There is a number of rather different scenarios which would seem, intuitively, to count as ‘time travel’—and a number of scenarios which, while sharing certain features with some of the time travel cases, seem nevertheless not to count as genuine time travel: [ 1 ]

Time travel Doctor . Doctor Who steps into a machine in 2024. Observers outside the machine see it disappear. Inside the machine, time seems to Doctor Who to pass for ten minutes. Observers in 1984 (or 3072) see the machine appear out of nowhere. Doctor Who steps out. [ 2 ] Leap . The time traveller takes hold of a special device (or steps into a machine) and suddenly disappears; she appears at an earlier (or later) time. Unlike in Doctor , the time traveller experiences no lapse of time between her departure and arrival: from her point of view, she instantaneously appears at the destination time. [ 3 ] Putnam . Oscar Smith steps into a machine in 2024. From his point of view, things proceed much as in Doctor : time seems to Oscar Smith to pass for a while; then he steps out in 1984. For observers outside the machine, things proceed differently. Observers of Oscar’s arrival in the past see a time machine suddenly appear out of nowhere and immediately divide into two copies of itself: Oscar Smith steps out of one; and (through the window) they see inside the other something that looks just like what they would see if a film of Oscar Smith were played backwards (his hair gets shorter; food comes out of his mouth and goes back into his lunch box in a pristine, uneaten state; etc.). Observers of Oscar’s departure from the future do not simply see his time machine disappear after he gets into it: they see it collide with the apparently backwards-running machine just described, in such a way that both are simultaneously annihilated. [ 4 ] Gödel . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship (not a special time machine) and flies off on a certain course. At no point does she disappear (as in Leap ) or ‘turn back in time’ (as in Putnam )—yet thanks to the overall structure of spacetime (as conceived in the General Theory of Relativity), the traveller arrives at a point in the past (or future) of her departure. (Compare the way in which someone can travel continuously westwards, and arrive to the east of her departure point, thanks to the overall curved structure of the surface of the earth.) [ 5 ] Einstein . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship and flies off at high speed on a round trip. When he returns to Earth, thanks to certain effects predicted by the Special Theory of Relativity, only a very small amount of time has elapsed for him—he has aged only a few months—while a great deal of time has passed on Earth: it is now hundreds of years in the future of his time of departure. [ 6 ] Not time travel Sleep . One is very tired, and falls into a deep sleep. When one awakes twelve hours later, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Coma . One is in a coma for a number of years and then awakes, at which point it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Cryogenics . One is cryogenically frozen for hundreds of years. Upon being woken, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Virtual . One enters a highly realistic, interactive virtual reality simulator in which some past era has been recreated down to the finest detail. Crystal . One looks into a crystal ball and sees what happened at some past time, or will happen at some future time. (Imagine that the crystal ball really works—like a closed-circuit security monitor, except that the vision genuinely comes from some past or future time. Even so, the person looking at the crystal ball is not thereby a time traveller.) Waiting . One enters one’s closet and stays there for seven hours. When one emerges, one has ‘arrived’ seven hours in the future of one’s ‘departure’. Dateline . One departs at 8pm on Monday, flies for fourteen hours, and arrives at 10pm on Monday.

A satisfactory definition of time travel would, at least, need to classify the cases in the right way. There might be some surprises—perhaps, on the best definition of ‘time travel’, Cryogenics turns out to be time travel after all—but it should certainly be the case, for example, that Gödel counts as time travel and that Sleep and Waiting do not. [ 7 ]

In fact there is no entirely satisfactory definition of ‘time travel’ in the literature. The most popular definition is the one given by Lewis (1976, 145–6):

What is time travel? Inevitably, it involves a discrepancy between time and time. Any traveller departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival…is the duration of the journey. But if he is a time traveller, the separation in time between departure and arrival does not equal the duration of his journey.…How can it be that the same two events, his departure and his arrival, are separated by two unequal amounts of time?…I reply by distinguishing time itself, external time as I shall also call it, from the personal time of a particular time traveller: roughly, that which is measured by his wristwatch. His journey takes an hour of his personal time, let us say…But the arrival is more than an hour after the departure in external time, if he travels toward the future; or the arrival is before the departure in external time…if he travels toward the past.

This correctly excludes Waiting —where the length of the ‘journey’ precisely matches the separation between ‘arrival’ and ‘departure’—and Crystal , where there is no journey at all—and it includes Doctor . It has trouble with Gödel , however—because when the overall structure of spacetime is as twisted as it is in the sort of case Gödel imagined, the notion of external time (“time itself”) loses its grip.