WWW.PRIMECLINICAL.COM

UB ENCOUNTER CONDITION CODES

These codes are required for completion of the form CMS-1450 for billing.

Form Locators (FLs) 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28 are Condition Codes.

Situational . The provider enters the corresponding code (in numerical order) to describe any of the following conditions or events that apply to this billing period.

Codes used for Medicare claims are available from Medicare contractors. Codes are also available from the NUBC ( www.nubc.org ) via the NUBC's Official UB-04 Data Specifications Manual.

Code Title Definition

Top of Page

Adjustment condition code clarification

It is very important to use the most appropriate condition code when adjusting claims.

Condition codes

Condition code D1

Condition code D9

Condition code quick reference

2021 E/M Guidelines: Understanding Total Visit Time

In this episode of the Listen-Up Series on 2021 E/M Guidelines , Lori Cox is joined by Elizabeth Hylton to talk about total visit time. They'll share how to correctly document the time you spend in patient care, what you can count and can't count on in E/M selection, and how to stand up to payer and auditor scrutiny. Plus, they discuss real-life office visit scenarios and answer questions like:

How is the new total visit time defined and what activities can be counted toward that total time?

What is the difference with the CMS prolonged services?

Can you explain the new HCPCS code G2211?

Are there guidelines on which calculation to use, MDM or time?

When time is documented, does time trump MDM?

Plus, they discuss AMA guidelines, the difference between the time standards and calculations, and more. This webinar will provide a better understanding of what to expect in provider notes and how to ensure compliant documentation.

To read the full conversation, check out the transcript below.

Who would benefit from watching this webinar?

Medical Billers

Medical Billing Managers (including Supervisors, Directors of Billing, etc.)

Medical Coders

Medical Coding Educators / Trainers

Medical Coding Managers (including Supervisors, Directors of Coding, etc.)

Medical Auditors

Healthcare Documentation Specialists

Documentation and Coding Managers / Directors

Healthcare Office Managers

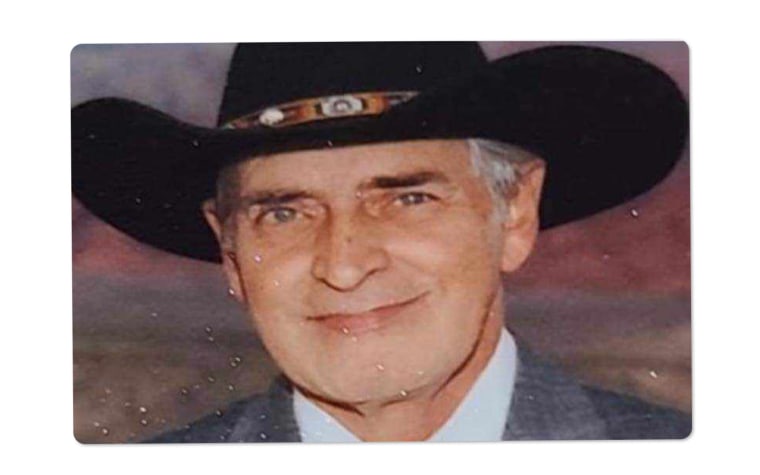

Presented by

Stephani Scott

Cpc, rhit / vice president of audit services / aapc /.

Stephani Scott has over 30 years of experience in the healthcare industry working closely with physicians and staff in Health Information Management. She has worked in a variety of settings including hospitals, long-term care, large multispecialty physician practice, and EHR software design and development. Scott was a part owner of a consulting company for many years providing services in best practices for physician practice management services including coding and documentation audits, compliance, and revenue cycle management. She has extensive experience in inpatient and outpatient auditing and coding compliance. Throughout her career, Scott has enjoyed teaching E/M coding, compliance, and EMR utilization to many physicians and staff locally and nationally.

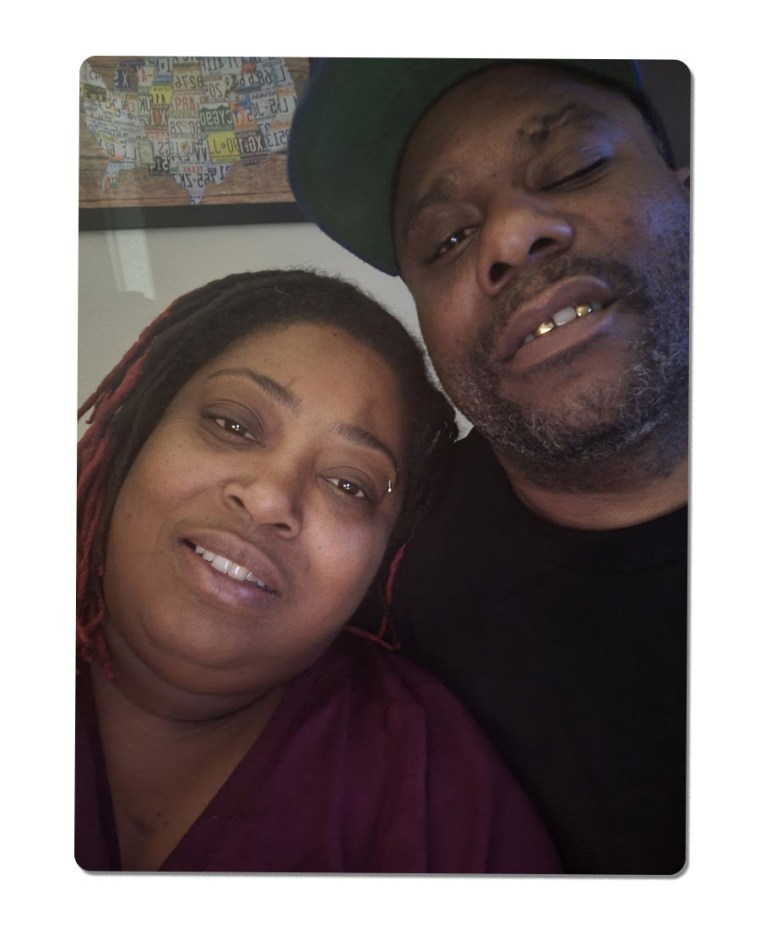

Elizabeth Hylton

Cpc, cemc / aapc services regional director.

Elizabeth Hylton began her coding career by identifying claims submission errors involving ICD-9 and CPT® codes on hospital claims. From there, she worked as a Charge Entry Specialist for a local family medicine practice. She worked her way up to Coding Tech I at Carolinas Medical Center- Northeast submitting claims for half of the team of 22 hospitalists and 8 Critical Care providers. From there, she accepted a position at Sanger Heart and Vascular Institute as a Front Desk Clerk who also functioned as the backup Coding Tech. She obtained her CPC in December of 2011 and in March of 2012 accepted a position as an Auditor/Educator for Carolinas HealthCare System. She went on to support 126 physicians in 22 practices with specialties that included Dermatology, Endocrinology, Gastroenterology, Hematology/Oncology, Internal Medicine, Orthopedic Surgery, Pediatrics, Cardiology, and Concierge Medicine. She obtained her CEMC certification in May of 2014. In January of 2015 she was offered a position as Business Office Supervisor for one of the larger physician groups within Carolinas HealthCare System, where she gained experience with Lean, and remained until she accepted the position of Director of Client Engagement with the AAPC Services in July of 2015 through September 2021.

Full Transcript

Stephani : Welcome, everybody, to our Listen-Up Series on 2021 E/M Guidelines. Today, we're going to be talking about total visit time. My name is Stephani Scott, and I will be your host today. I have worked in the healthcare industry for over 25 years. During that time, I've had the pleasure of working in a variety of different settings, including acute hospital, long-term care, large multi-specialty physician groups, and I've worked for a major EMR vendor doing design and development work. For several years, I was a part-owner of a consulting company in which we provided services for physician practice management, including coding, billing, and revenue cycle. Currently, I am the vice-president for AAPC's audit services. My guest today is Elizabeth Hylton. Elizabeth, will you introduce yourself?

Elizabeth : Absolutely. I am a regional director with AAPC Audit Services Group. I have about 17 years’ experience in the healthcare administration setting. I hold the credentials of CPC and CEMC, and I've had the privilege of working pretty much every line of service in the admin field of healthcare. I started off as a front desk person in a family practice clinic, and gradually worked my way through the revenue cycle, from denials all the way to claims processing, and then auditing in a retrospective manner. So, I've pretty much done it all. If you can do it administratively in healthcare, I've done it.

Stephani : Well, that's great. You're perfect one to join me today for our webinar. Okay. First, what we thought we would do is talk about the new time-based definition and how the calculations work. Then I actually pulled some real-life office visit scenarios. Obviously, we've redacted them and tweaked them just a little bit, but these are scenarios that we've come across over the last several months. And then finally, Elizabeth, I wanted to go over some common questions that we keep getting from different organizations.

Elizabeth : Sounds great.

Stephani : So, okay, perfect. With that, let's go ahead and get started. So we now have these two different time standards and calculations. Elizabeth, can you tell us what are the difference between these two?

Elizabeth : Absolutely. So, under the system we're used to, '95/'97 guidelines, we had to put a statement in there that showed we spent greater than 50% of a total visit face-to-face with our patient counseling and coordinating care. Now, this is still going to be the case with our other E/M categories, just not the office and outpatient setting. For that under our new 2021 calculation, it is going to be based just on total visit time on the day of the patient encounter. So much, much simpler in the office and outpatient world.

Stephani : Okay. Thank you. So Elizabeth, tell us exactly how this new total visit time is defined and what activities can be counted towards that total time.

Elizabeth : That's a great question. So total time is being defined as what is spent on the day of the patient encounter. It is going to include both face-to-face and non-face-to-face activities. And we have it broken down on the slide here that we're referencing. We have things that we can include and things we can't include. So things we can include, prep on the same day, obtaining and reviewing history from our patient's records, the exam that we perform with them, any counseling and ordering of tests, medications, and procedures, okay? So things that are typically associated with the evaluation and management service that our providers historically have not been able to count like their prep work.

Charting is also included on this, care coordination. All of those services that previously we couldn't really get credit for because they didn't take place face-to-face with the patient, now we can include. And no longer do we need to use the statement of greater than 50% of time was spent in counseling. It's just the total time that you spend taking care of your patient on that day.

Stephani : Okay. So what types of activities are not included?

Elizabeth : So some of the things that we would not include, we have to bear in mind that this is provider time only. It is not going to count staff time. It is not going to count the separately reported tests or procedures that you perform on the day. So if there's a CPT code associated with something that you're doing outside of the evaluation and management service, the time that you spend performing those identified CPT codes is not included. Slow charting is also not something that you would include.

I had a practice who was getting ready to go to a new EMR system in February. And they're very concerned about having two learning curves to come up to, but we had to make sure we were very clear there's a reasonable expectation surrounding how long it takes to chart, and that's what we count. Not necessarily coming up to a learning curve in an EMR. And then, of course, any elements that are performed on a different date. So depending on your provider's flow and the way they like to practice medicine, if they are doing prep work the day before they see a patient or they're doing review the day after they see a patient, those elements will not count. It has to be elements that are performed on the same calendar date as the patient encounter.

Stephani : Okay. Great. That's some good insight. Okay. On this slide deck, we've broken out the different time ranges. So Elizabeth, kind of walk us through the ranges for new patient and established patient.

Elizabeth : Okay. This is the first time when I reviewing these guidelines initially that I went, "Whoa, that's different," because we're very used to seeing a static point in time assigned to these codes. You know, it's been very easy for me previously to just rattle off, "Oh yeah, you need 15 minutes for a 99213," or, "You need 25 minutes for a 99214." That's not the case anymore. Now it's defined by a range of time and your static point will fall into this range.

So as you can see, there's kind of a pattern with this. New patients are gonna start at 15 minutes and they're gonna go up in 15-minute increments. So once you hit 30 minutes, you're at a 99203, once you hit 45, you're at a 99204, 60 for 99205, and so on versus under the established patient rules, we have to start with 10 minutes for a 99212, and then we billed in 10-minute increments. You start with a 99213 once you hit 20 minutes, 30 minutes for a 99214, and so on.

So we've been encouraging our providers, you know, you have to understand you're now being defined by a range of time, but please do not document a range of times. Tell us the static amount of time that you spent with your patient on this day, and then a coder will assign the appropriate E/M based on what you're telling us in documentation.

Stephani : Okay. Great. So there has been some confusion on whether or not CMS has adopted these time ranges. Can you help us with that?

Elizabeth : From my understanding, they have adopted this. This is in the CPT books for 2021. The only place where CMS kind of gets a little different from AMA is going to be with calculation of prolonged services. Those rules are a little bit different.

Stephani : Okay. Thanks for clarifying. Let's go ahead and talk about the prolonged services. So Elizabeth, help us define the AMA's guideline here.

Elizabeth : All right. So AMA has released a new code for 2021 CPT code set, and this is 99417. This will define 15 minutes of prolonged office or other outpatient evaluation and management services beyond the total time of the primary procedure which has been selected using total time. So we can only use these with 99205 and 99215 only, okay? These are not going to apply to the remainder of the office and outpatient code set. We have to remember that for our other categories, we're still going to continue to use the prolonged services codes we're used to seeing represented by the range of 99354 to 99359, 99415 and 99416.

So, CPT has given us some really good examples of how to calculate this when we're reporting 99417, an initial time unit of 15 minutes should be added once the minimum time in the primary E/M code has been surpassed by that 15 minutes. So, for example, we're not gonna report 99417 until at least 15 minutes of time beyond 60 minutes i.e., 75 minutes has been accumulated. The same is true for 99215. We have to get to 15 minutes past 40 minutes or 55 minutes before we can bill prolonged services.

Stephani : Okay. So on this slide, we've got those time ranges for prolonged new patient and prolonged established patient. Now, does the times stop, the prolonged time maximum stop at the four units that I have listed on the slide, or does that continue on?

Elizabeth : It can continue based on how much time is being spent with the patient, and it does not have to be contiguous, it can be incremental. So let's say you spend 40 minutes this first hour, and then you come back to the patient later in the day and you're spending more time. All of it is cumulative. Again, based on the date of service of the patient encounter. So if you're spending units past four, then we just have to remember it's in 15-minute blocks. So we have to balance how much time is being spent in what we're describing in our notes versus math here. So we have to make sure that those two things are lining up, but you can bill past four units.

Stephani : Okay. All right. Thank you. So now tell us what the difference is with the CMS prolonged services.

Elizabeth : All right. So Medicare has decided to assign a status indicator of invalid to CPT 99417. Meaning if you were to bill that code to CMS, they would not return payment for it. Instead, they have adopted their own HCPCS code for this, which is G2212. The description is similar. It's the prolonged office or other outpatient evaluation and management services beyond the maximum required time of the primary procedure which has been selected using total time on the date of the primary service, each additional 15 minutes by the physician or qualified healthcare professional, with or without direct patient context.

And the thing we have to remember here is this code kicks in for time beyond the maximum required time of the primary procedure. Once again, it can only be used with 99205 and 99215. You will not be able to report this code on the same date of service as our other prolonged services codes, 99354 to 99359, 999415, and 99416. And we have to remember we cannot report G2212 for any time unit less than 15 minutes. There is not a midpoint to this code. We have to satisfy 15 full minutes before we can bill it.

Stephani : Okay. So on this slide, we've broken out those specific time ranges. So, for example, if I'm looking at a new patient record and my total time were 90 minutes for CMS, could I also bill 99205 and the G2212 with one unit?

Elizabeth : So based on this, if we have a new patient for 99205, we would not be able to bill the G2212 because we've not surpassed that 15-minute mark. Well, wait a minute, hold on. Let me look at this. It's early in the morning, my brain is not massing correctly. So G2212 does describe that range of time. If we look at 99205, it does appear based on this table, we will be able to bill the G2212 on 90 minutes for a new patient. What we have to remember is that the full 15 minutes are past the max time of the code.

So, whereas we are looking at less time under the AMA guidelines, Medicare requires more. My rule of thumb talking to these providers is that you have to hit at least 15 minutes past the maximum amount of time for this code before you even consider upending G2212. And that's true for both new and established categories.

Stephani : Okay. So the 89 minutes is that 15-minute mark for new, and the 69 is that 15-minute mark for 50. Okay. Got it.

Elizabeth : Correct.

Stephani : Thank you. All right. So CMS released this new HCPCS code G2211, and we have just been getting a ton of questions about this new code and how practices can get paid for it. So, Elizabeth, can you help us better understand this new code?

Elizabeth : Sure, absolutely. This is something that CMS released to describe visit complexity that was inherent to evaluation and management associated with medical care services that serve as the continuing focal point for all needed healthcare services and/or with medical care services that are part of ongoing care related to a patient's single, serious condition or a complex condition. The spirit of the code was great. And when I read this, I instantly thought, wow, this is like the spirit of transitional care management without actually having to have the inpatient admission associated with it and all the rules that go with that code set. This is wonderful. It's gonna describe additional time, intensity, and practice expense for services that are building that longstanding relationship and addressing the majority of patient healthcare needs over time.

This is exactly what we're seeing with some of our older population. They have multiple chronic conditions that are being evaluated and the physician should be compensated for the care relating to those conditions. But then literally at the 11th hour, 2:00 a.m. on December 1st, Medicare came back and said, "We're not going to price this code. It is not going to be effective for payment until January 1st, 2024." So we have to wait on this for about three more years, and then we will be able to account for increased visit complexity.

Stephani : Okay. Thank you. A little disappointing we're not able to use it yet, but it's good that it's coming in the future. Something to look forward to, for sure.

Elizabeth : Absolutely.

Stephani : Okay. So let's go over some scenario. So Elizabeth, I'm just gonna pass this directly over to you.

Elizabeth : Okay. Fantastic. So let's talk about a patient. Their chief complaint is going to be a goopy eye. Their mom reports the patient woke up with left eye matted shut. The eye is itchy and watery. The mother denied the patient having any fever, ear pain, rhinorrhea, or rash. Patient's not on any medication. The provider documents an exam of vision, right 10 out of 10, left 10 out of 13, eye is injected, pupils equal round reactive to light and accommodation, extraocular movement's intact, no periorbital edema, or erythema, or tenderness. And then they give an assessment of conjunctivitis. They give a prescription for Polytrim drops, three drops to the affected eye five times a day for seven days. And we instructed the mom to call if the patient develops a fever. Provider also denotes a total visit time of 12 minutes. So based on that documentation of time, we are going to have a 99212 as our level.

Stephani : Okay. Perfect. Now I noticed on that time, all it says is just the minutes, the total visit time 12 minutes. Is that gonna suffice the documentation requirement? Don't we have to put more to that?

Elizabeth: It's minimally acceptable. Now me as an auditor, my brain does a thing where I would probably want to see more, but the provider is saying that the total visit time on the date of service is 12 minutes. So it is sufficient. If it were me, I would probably educate them to flesh that out just a little bit. Total visit time spent in E/M service exclusively 12 minutes, and you're good to go.

Stephani : Okay. So this next scenario kind of addresses that. Can you help us walk through it?

Elizabeth : Absolutely. So we have a statement that the provider spent greater than 45 minutes with the patient and greater than 50% of that counseling on diagnosis treatments, previous test results, histories, and updating EMR as described above. Now that is absolutely textbook from a 1995/1997 documentation standpoint. For 2021, we're gonna switch that up a little bit. And the provider will now document, "A total of 60 minutes was spent today reviewing the patient's diagnostic tests, assessing and examining the patient and documenting. None of this time was spent performing separately billable procedures or ancillary services.

So what the provider does well with this 2021 is he gives us the exact total time that was spent with the patient. He avoided language like at a minimum or approximately. It was 60 minutes that was spent today. So he's letting us know this was all spent on the day of the patient encounter. The documentation of what was performed ideally is going to be patient-specific. Now I underlined this on my notes, reviewing patient's diagnostic tests, assessing and examining the patient and documenting, that is not a requirement of 2021.

However, many organizations that I've provided this training to, they have adopted it from a best practice standpoint to support individuality from one patient to the next. I would caution our providers to be careful of using templates that look identical from one patient to the next. Copy-paste is still going to be a concern in 2021. And I suspect given time is one of only two components used for selecting levels in the office and outpatient setting, time-based billing is going to come under even greater scrutiny. So we have to be careful that what we're saying we're doing from a time perspective is backed up with what's actually being done in documentation.

Stephani : That's some good advice, Elizabeth. Thank you. Okay. So we have a third scenario with a prolonged time. Can you walk us through this one?

Elizabeth : Sure. So we have an established patient here, so we're already going to be looking at our...if we're planning on doing a prolonged service, it's gotta be at least a 99215. The patient presents with fluid retention and shortness of breath. The assessment and plan diagnose this patient with congestive heart failure. The provider goes on to say that they spent 62 minutes obtaining records from primary care, evaluating their patient, and discussing treatment options to include fluid restriction, a low-salt diet, and compression hose.

If the patient continues to retain fluid, we'll consider low-dose Lasix. So under the AMA guidelines, this is enough to substantiate both the 99215 and one unit of 99417. Given the fact this was congestive heart failure, I instantly think this is probably a Medicare-aged patient, and under CMS rule, this will only substantiate a 99215. It will not meet the threshold in order to bill the additional 99417, or in the Medicare patient's case, the G2212.

Stephani : All right. Thank you, Elizabeth. Yep. So let's move on to some common questions that we keep getting. So I'll go ahead and read the questions. Are there guidelines on which calculation to use, MDM or time?

Elizabeth : The guidelines that we have specifies that an E/M service should be selected based on either MDM or time? So whichever one is beneficial to the provider, if the provider substantiate their level on time, MDM does not also have to be documented and vice versa. If the time and MDM are both documented and they can split, so let's say one component supports a lower level than the other, we'll use whichever component is beneficial to the provider.

Stephani : Okay. So the next question is when time is documented, does time trump MDM?

Elizabeth : This is a great question. Not always is the answer. For example, if by time a provider supports a 99213, let's say they spent 20 minutes with their patient, but the medical decision-making supports a level four because they have management of two stable chronic conditions with moderate risk to the patient, and the provider bills that level four, the level is supported by their medical decision-making as outlined in documentation. There was initially some discussion amongst providers that they just bill based on time since it was easier. And if that's all they have to put in their note, cool, that's what we're gonna do.

And we had to remind our providers you have to understand, in some cases, they'd be selling themselves short because of how time had been restructured now with that range instead of a static point, but to bill based solely on time would actually hurt their bottom line. So time does not always trump MDM. And I don't feel like if a provider substantiates a greater level of MDM, it would be fair to rely on the time. Their cognitive work is right there on the paper for us to see, and it may exceed the amount of time that was spent.

Stephani : Thank you. That's some great insight. So our last question is if MDM supports a 99215, however, the total visit time supports a 99214, should 99214 be reported to avoid reporting a level five as a target? So we all know about the E/M bell curve and the watchful eyes of the payers on those higher levels. So in this case, what should we do?

Elizabeth : Well, I tend to take those bell curves with a grain of salt. They are excellent tools to establish a baseline and a benchmark and help our providers understand what their colleagues nationwide are doing. However, at some point, we have to stop thinking about those higher levels as a target that we don't want on our backs. If a provider is supporting their MDM complexity, we have to allow credit for the cognitive work that's associated with the complexity and risk. Usually, when I'm auditing, I'm looking at the medical decision-making first because that's really the clinical determination that the provider is making. And then I'll use time as a fallback if I need it.

I will very rarely look at time and pull a provider's level down, especially if he's given me a beautiful description of a high MDM. To me, that's an unfair penalty and way too stringent of a stance. So if they support their MDM but their time supports a lower level, I would go with MDM because once again, that's measurement of the provider's cognitive effort on paper and they should be giving credit for the work that they're performing.

Stephani : That's excellent advice. Well, this concludes our Listen-Up Series on the 2021 E/M Guidelines, understanding total times for those guidelines. Elizabeth, thank you so very much for being my guest. And thank you, everyone, for joining us. Have a great day.

Want more than this webinar?

Our experts are standing by, ready to help you with challenges related to E/M guidelines, claim denials, data files, staff training, and more.

You might also like

- Evaluation and Management

- Documentation

- Business Solutions

Have a question?

Better revenue starts here..

Medicare codes

Nov 16, 2009 | Medical billing basics | 1 comment

D1 Claim/service denied. Level of subluxation is missing or inadequate. D2 Claim lacks the name, strength, and dosage of the drug furnished. D3 Claim/service denied because information to indicate if the patient owns the equipment that requires the part or supply was missing. D4 Claim/service does not indicate the period of time for which this will be needed. D5 Claim/service denied. Claim lacks individual lab codes included in the test. D6 Claim/service denied. Claim did not include patient’s medical record for the service. D7 Claim/service denied. Claim lacks date of patient’s most recent physician visit. D8 Claim/service denied. Claim lacks indicator that “xray is available for review.” D9 Claim/service denied. Claim lacks invoice or statement certifying the actual cost of the lens, less discounts or the type of intraocular lens used. D10 Claim/service denied. Completed physician financial relationship form not on file. D11 Claim lacks completed pacemaker registration form. D12 Claim/service denied. Claim does not identify who performed the purchased diagnostic test or the amount you were charged for the test. D13 Claim/service denied. Performed by a facility/supplier in which the ordering/referring physician has a financial interest.

Remark codes must be used to relay service-specific Medicare informational messages that cannot expressed with a reason code. Medicare remark codes are maintained by HCFA. Remark codes and messages must be used whenever they apply. Although contractors may use their discretion to determine when certain remark codes apply, they do not have discretion as to whether to use an applicable remark code in a remittance notice. A limitation of liability message (m25-M27) must be used where applicable. An unlimited number of Medicare line level remark codes may be entered as warranted in an X12 835 Remittance Advice; there is a limit of 5 line level remark code entries in a NSF Remittance Advice and on a standard paper remittance notice. a. Line Level Remark Codes Code Value Description

M1 X-ray not taken within the past 12 months or near enough to the start of treatment. M2 Not paid separately when the patient is an inpatient. M3 Equipment is the same or similar to equipment already being used. M4 This is the last monthly installment payment for this durable medical equipment. M5 Monthly rental payments can continue until the earlier of the 15th month from the first rental month, or the month when the equipment is no longer needed. M6 You must furnish and service this item for as long as the patient continues to need it. We can pay for maintenance and/or servicing for every 6 month period after the end of the 15th paid rental month or the end of the warranty period. M7 No rental payments after the item is purchased, or after the total of issued rental payments equals the purchase price. M8 We do not accept blood gas tests results when the test was conducted by a medical supplier or taken while the patient is on oxygen. M9 This is the tenth rental month. You must offer the patient the choice of changing the rental to a purchase agreement. M10 Equipment purchases are limited to the first or the tenth month of medical necessity.

Medicare denial reason code -1 Medicare denial reason code – 2 Medicare denial reason code – 3 Denial EOB Medicare EOB Denial claim example Denial claim Medicare denial codes For full list

M1 X-ray not taken within the past 12 months or near enough to the start of treatment.

Why am I getting this rejection? How do I get paid?

Medical Billing Update

- Insurance denial code full List – Medicare and Medicaid

- Late filing reduction and Time Limits for Filing Part B Medicare Claims

- Ask people to take pictures for you

- Can PCP disenroll a patient from the memebr panel list

- Can we billed Medicaid patient for Medicare coins ?

Recent Posts

- Origin and Destination modifiers in Ambulance billing

- CPT code 88120, 81161 – 81408 – molecular cpt codes

- Denial – Covered by capitation , Modifier inconsistent – Action

- CPT code 10040, 10060, 10061 – Incision And Drainage Of Abscess

- CPT Code 0007U, 0008U, 0009U – Drug Test(S), Presumptive

- Medical billing basics

All the contents and articles are based on our search and taken from various resources and our knowledge in Medical billing. All the information are educational purpose only and we are not guarantee of accuracy of information. Before implement anything please do your own research. If you feel some of our contents are misused please mail us at medicalbilling4u at gmail dot com. We will response ASAP.

Jurisdiction E - Medicare Part A

California, Hawaii, Nevada, American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands

- Noridian Medicare Portal (NMP) Login

OPPS Payment Status Indicators - JE Part A

Browse by Provider Type

- Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) Hospital

- Critical Access Hospital (CAH)

- Comprehensive Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF)

- End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD)

- Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)

- Fee-for-Time Compensation Arrangements and Reciprocal Billing

- Inpatient Psychiatric Facility (IPF)

- Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility (IRF)

- Long Term Care Hospital (LTCH)

- Mental Health

- Military Treatment Facility (MTF)

- Nonphysician Practitioner (NPP)

- Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS)

- Outpatient Therapy

- Provider Based Facilities

- Rural Emergency Hospital (REH)

- Rural Health Clinic (RHC)

- Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF)

- Sleep Medicine

OPPS Payment Status Indicators

- CMS Addendum A and Addendum B Updates

© 2024 Noridian Healthcare Solutions, LLC Terms & Privacy

End User Agreements for Providers

Some of the Provider information contained on the Noridian Medicare web site is copyrighted by the American Medical Association, the American Dental Association, and/or the American Hospital Association. This includes items such as CPT codes, CDT codes, ICD-10 and other UB-04 codes.

Before you can enter the Noridian Medicare site, please read and accept an agreement to abide by the copyright rules regarding the information you find within this site. If you choose not to accept the agreement, you will return to the Noridian Medicare home page.

THE LICENSES GRANTED HEREIN ARE EXPRESSLY CONDITIONED UPON YOUR ACCEPTANCE OF ALL TERMS AND CONDITIONS CONTAINED IN THESE AGREEMENTS. BY CLICKING ABOVE ON THE LINK LABELED "I Accept", YOU HEREBY ACKNOWLEDGE THAT YOU HAVE READ, UNDERSTOOD AND AGREED TO ALL TERMS AND CONDITIONS SET FORTH IN THESE AGREEMENTS.

IF YOU DO NOT AGREE WITH ALL TERMS AND CONDITIONS SET FORTH HEREIN, CLICK ABOVE ON THE LINK LABELED "I Do Not Accept" AND EXIT FROM THIS COMPUTER SCREEN.

IF YOU ARE ACTING ON BEHALF OF AN ORGANIZATION, YOU REPRESENT THAT YOU ARE AUTHORIZED TO ACT ON BEHALF OF SUCH ORGANIZATION AND THAT YOUR ACCEPTANCE OF THE TERMS OF THESE AGREEMENTS CREATES A LEGALLY ENFORCEABLE OBLIGATION OF THE ORGANIZATION. AS USED HEREIN, "YOU" AND "YOUR" REFER TO YOU AND ANY ORGANIZATION ON BEHALF OF WHICH YOU ARE ACTING.

LICENSE FOR USE OF "PHYSICIANS' CURRENT PROCEDURAL TERMINOLOGY", (CPT) FOURTH EDITION

End User/Point and Click Agreement:

CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2002-2020 American Medical Association (AMA). All Rights Reserved. CPT is a trademark of the AMA.

You, your employees and agents are authorized to use CPT only as contained in the following authorized materials: Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs), training material, publications, and Medicare guidelines, internally within your organization within the United States for the sole use by yourself, employees and agents. Use is limited to use in Medicare, Medicaid, or other programs administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). You agree to take all necessary steps to ensure that your employees and agents abide by the terms of this agreement. You acknowledge that the AMA holds all copyright, trademark, and other rights in CPT.

Any use not authorized herein is prohibited, including by way of illustration and not by way of limitation, making copies of CPT for resale and/or license, transferring copies of CPT to any party not bound by this agreement, creating any modified or derivative work of CPT, or making any commercial use of CPT. License to use CPT for any use not authorized here in must be obtained through the AMA, CPT Intellectual Property Services, 515 N. State Street, Chicago, IL 60610. Applications are available at the AMA Web site, https://www.ama-assn.org .

This product includes CPT which is commercial technical data and/or computer data bases and/or commercial computer software and/or commercial computer software documentation, as applicable which were developed exclusively at private expense by the American Medical Association, 515 North State Street, Chicago, Illinois, 60610. U.S. Government rights to use, modify, reproduce, release, perform, display, or disclose these technical data and/or computer data bases and/or computer software and/or computer software documentation are subject to the limited rights restrictions of DFARS 252.227-7015(b)(2)(June 1995) and/or subject to the restrictions of DFARS 227.7202-1(a)(June 1995) and DFARS 227.7202-3(a)June 1995), as applicable for U.S. Department of Defense procurements and the limited rights restrictions of FAR 52.227-14 (June 1987) and/or subject to the restricted rights provisions of FAR 52.227-14 (June 1987) and FAR 52.227-19 (June 1987), as applicable, and any applicable agency FAR Supplements, for non-Department Federal procurements.

AMA Disclaimer of Warranties and Liabilities CPT is provided "as is" without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, including but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. The AMA warrants that due to the nature of CPT, it does not manipulate or process dates, therefore there is no Year 2000 issue with CPT. The AMA disclaims responsibility for any errors in CPT that may arise as a result of CPT being used in conjunction with any software and/or hardware system that is not Year 2000 compliant. No fee schedules, basic unit, relative values or related listings are included in CPT. The AMA does not directly or indirectly practice medicine or dispense medical services. The responsibility for the content of this file/product is with Noridian Healthcare Solutions or the CMS and no endorsement by the AMA is intended or implied. The AMA disclaims responsibility for any consequences or liability attributable to or related to any use, non-use, or interpretation of information contained or not contained in this file/product.

CMS Disclaimer The scope of this license is determined by the AMA, the copyright holder. Any questions pertaining to the license or use of the CPT must be addressed to the AMA. End Users do not act for or on behalf of the CMS. The CMS DISCLAIMS RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY LIABILITY ATTRIBUTABLE TO END USER USE OF THE CPT. The CMS WILL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIMS ATTRIBUTABLE TO ANY ERRORS, OMISSIONS, OR OTHER INACCURACIES IN THE INFORMATION OR MATERIAL CONTAINED ON THIS PAGE. In no event shall CMS be liable for direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages arising out of the use of such information or material.

This license will terminate upon notice to you if you violate the terms of this license. The AMA is a third-party beneficiary to this license.

LICENSE FOR USE OF "CURRENT DENTAL TERMINOLOGY", ("CDT")

End User/Point and Click Agreement

These materials contain Current Dental Terminology, (CDT), copyright © 2020 American Dental Association (ADA). All rights reserved. CDT is a trademark of the ADA.

1. Subject to the terms and conditions contained in this Agreement, you, your employees, and agents are authorized to use CDT only as contained in the following authorized materials and solely for internal use by yourself, employees and agents within your organization within the United States and its territories. Use of CDT is limited to use in programs administered by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). You agree to take all necessary steps to ensure that your employees and agents abide by the terms of this agreement. You acknowledge that the ADA holds all copyright, trademark and other rights in CDT. You shall not remove, alter, or obscure any ADA copyright notices or other proprietary rights notices included in the materials.

2. Any use not authorized herein is prohibited, including by way of illustration and not by way of limitation, making copies of CDT for resale and/or license, transferring copies of CDT to any party not bound by this agreement, creating any modified or derivative work of CDT, or making any commercial use of CDT. License to use CDT for any use not authorized herein must be obtained through the American Dental Association, 211 East Chicago Avenue, Chicago, IL 60611. Applications are available at the American Dental Association web site, http://www.ADA.org .

3. Applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation Clauses (FARS)\Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) Restrictions Apply to Government use. Please click here to see all U.S. Government Rights Provisions .

4. ADA DISCLAIMER OF WARRANTIES AND LIABILITIES. CDT is provided "as is" without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied, including but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. No fee schedules, basic unit, relative values or related listings are included in CDT. The ADA does not directly or indirectly practice medicine or dispense dental services. The sole responsibility for the software, including any CDT and other content contained therein, is with (insert name of applicable entity) or the CMS; and no endorsement by the ADA is intended or implied. The ADA expressly disclaims responsibility for any consequences or liability attributable to or related to any use, non-use, or interpretation of information contained or not contained in this file/product. This Agreement will terminate upon notice to you if you violate the terms of this Agreement. The ADA is a third-party beneficiary to this Agreement.

5. CMS DISCLAIMER. The scope of this license is determined by the ADA, the copyright holder. Any questions pertaining to the license or use of the CDT should be addressed to the ADA. End users do not act for or on behalf of the CMS. CMS DISCLAIMS RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY LIABILITY ATTRIBUTABLE TO END USER USE OF THE CDT. CMS WILL NOT BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIMS ATTRIBUTABLE TO ANY ERRORS, OMISSIONS, OR OTHER INACCURACIES IN THE INFORMATION OR MATERIAL COVERED BY THIS LICENSE. In no event shall CMS be liable for direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages arising out of the use of such information or material.

LICENSE FOR NATIONAL UNIFORM BILLING COMMITTEE ("NUBC")

Point and Click American Hospital Association Copyright Notice

Copyright © 2021, the American Hospital Association, Chicago, Illinois. Reproduced with permission. No portion of the AHA copyrighted materials contained within this publication may be copied without the express written consent of the AHA. AHA copyrighted materials including the UB-04 codes and descriptions may not be removed, copied, or utilized within any software, product, service, solution or derivative work without the written consent of the AHA. If an entity wishes to utilize any AHA materials, please contact the AHA at 312-893-6816

Making copies or utilizing the content of the UB-04 Manual or UB-04 Data File, including the codes and/or descriptions, for internal purposes, resale and/or to be used in any product or publication; creating any modified or derivative work of the UB-04 Manual and/or codes and descriptions; and/or making any commercial use of UB-04 Manual / Data File or any portion thereof, including the codes and/or descriptions, is only authorized with an express license from the American Hospital Association.

To obtain comprehensive knowledge about the UB-04 codes, the Official UB-04 Data Specification Manual is available for purchase on the American Hospital Association Online Store . To license the electronic data file of UB-04 Data Specifications, contact AHA at (312) 893-6816. You may also contact AHA at [email protected] .

Consent to Monitoring

Warning: you are accessing an information system that may be a U.S. Government information system. If this is a U.S. Government information system, CMS maintains ownership and responsibility for its computer systems. Users must adhere to CMS Information Security Policies, Standards, and Procedures. For U.S. Government and other information systems, information accessed through the computer system is confidential and for authorized users only. By continuing beyond this notice, users consent to being monitored, recorded, and audited by company personnel. Unauthorized or illegal use of the computer system is prohibited and subject to criminal and civil penalties. The use of the information system establishes user's consent to any and all monitoring and recording of their activities.

Note: The information obtained from this Noridian website application is as current as possible. There are times in which the various content contributor primary resources are not synchronized or updated on the same time interval.

This warning banner provides privacy and security notices consistent with applicable federal laws, directives, and other federal guidance for accessing this Government system, which includes all devices/storage media attached to this system. This system is provided for Government authorized use only. Unauthorized or improper use of this system is prohibited and may result in disciplinary action and/or civil and criminal penalties. At any time, and for any lawful Government purpose, the government may monitor, record, and audit your system usage and/or intercept, search and seize any communication or data transiting or stored on this system. Therefore, you have no reasonable expectation of privacy. Any communication or data transiting or stored on this system may be disclosed or used for any lawful Government purpose.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

How to Read Your Healthcare Provider's Prescription

Parts of a prescription, prescription example.

- Newer and Simpler Information

What to Do if You Can’t Read It

A modern doctor's prescription is often digital, and you may not see it when sent from your healthcare provider directly to the pharmacy. For some controlled substances, digital prescriptions are even required. But when you need to read a prescription, it can still be pretty hard to decipher.

Knowing how to read a prescription will help you understand the meanings of various notations about what drug to use, how it should be dispensed, and how and when to take your medication.

This article will help you understand the abbreviations included when your healthcare provider writes a prescription. You'll be better equipped to decode a prescription or ask questions , which can help you avoid a medication error and give you better insight into your treatment.

Rockaa / Getty Images

A prescription is always written in a specific way. It identifies you and your healthcare provider, lists the specific medication prescribed, and includes details such as how to take the medication.

Identification

A prescription will always identify the healthcare provider who ordered the medication and the person who needs it. Your first and last name, along with a date of birth, are displayed. Some states require an address.

Some of the provider's information will be obvious to you, such as the name and office you visit. Other elements, including the license number, may be unfamiliar. You may see a National Provider Identifier (NPI) number, which is issued by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

If your prescription is for certain controlled substances, it also will include a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) registration number.

Medication: The Rx Details

Your prescription (marked by the Rx symbol) needs to include the type of medication, typically with both the brand name and a generic name, when available. For example, a prescription for the common cholesterol medication Lipitor ( atorvastatin ) may carry both names, but the instructions for filling with a generic are included.

This part of the prescription also includes the strength of the drug (how many milligrams, for example) and the tablet, capsule, or other form in which your healthcare provider wants you to take it. A note called "Disp" refers to this information about how the drug should be dispensed.

The information includes how often you take your medication and the reason for it, called the indication. This is often on the same line as "sig," an abbreviation for the Latin word signetur that refers to the written instructions.

These are some of the notations about how to take medication that are commonly found on prescriptions:

- PO means orally

- QD means once a day

- BID means twice a day

- QHS means before bed

- Q4H means every 4 hours

- QOD means every other day

- PRN means as needed

- a.c. means before a meal

- p.c. means after a meal

Abbreviations about the route of administration (how you take the medication) include the following:

- q.t.t. means drops

- OD means in the right eye (eye drops)

- OS means in the left eye (eye drops)

- OU means in both eyes (eye drops)

- IM means intramuscularly (muscle injection)

- Subq means subcutaneous (under-the-skin injection)

- IV means intravenous (injection in the vein)

You may see a symbol on your script that looks like a "T" with a dot at the top of it. This abbreviation means one pill. There may be one to 4 Ts with dots at the top of them signifying one to four pills.

Other Prescription Information

Additional details often found in a prescription include whether it can be refilled, and if so, the number of times. It also includes permission for substitutes, if necessary, along with a healthcare provider's signature and the date.

Some prescriptions include "dispense as written," or DAW, in the instructions. This means that no substitute should be used.

Consider a hypothetical prescription for penicillin written as follows:

- Rx Pen VK 250/ml 1 bottle

- iiss ml qid X 7d

Here is what the notation on this prescription means:

- The medication is Penicillin VK and the healthcare provider ordered one 250 milliliter (ml) bottle, which is about 8 ounces.

- The "ii" means 2 and "ss" means 1/2 which translates to 2 1/2 ml, or 1/2 teaspoon.

- The qid X 7d means four times each day for seven days.

Using the information noted on this prescription, the pharmacist will provide a bottle of Penicillin VK with label directions indicating that 1/2 teaspoon of the medication should be taken four times each day for seven days.

As with other medications, your healthcare provider information (name, office address, NPI, etc.) will appear on the penicillin prescription. So will a signature and the date.

Newer Prescriptions Are Often Simpler

In the digital era, prescriptions may be simpler to read. Having a printed prescription means you won't have to try to read or understand your provider's handwriting. Even when the prescription is sent directly to the pharmacy, your provider will give you printed information about your medication and the condition it's used to treat.

Pharmacies, too, have easy-to-read information in plain language. Usually, you can receive these forms when you pick up the drug. If not, ask the pharmacist if you have questions. They are skilled professionals who are well-trained to answer your questions regarding medication dosages, side effects, and adverse effects.

If you don't understand your prescription or the details about it, ask questions. Healthcare providers want you to know what you're taking and why, and feel confident about your treatment.

If you suspect an error on your prescription, notify your healthcare provider and pharmacist right away. Keep an eye on all fields; it's possible to have the right medication but the wrong dosage, for example, or for a provider and pharmacy to miss a potentially serious drug interaction with something you already take.

There's a good chance that your healthcare provider sends prescriptions electronically and directly to the pharmacy, but you may still need to read a prescription yourself. Decoding a prescription is an important skill that can limit any errors and keep you an active partner in your care.

The notations on your prescription are part of a standard format, written in both English and Latin. It includes three basic parts: information about you, information about your provider, and information about the drug they're prescribing and the reason you need it.

Typically, your pharmacist also will provide information about your prescriptions and include printed material that comes with your medications.

Everson J, Cheng AK, Patrick SW, Dusetzina SB. Association of Electronic Prescribing of Controlled Substances With Opioid Prescribing Rates . JAMA Netw Open . 2020 Dec 1;3(12):e2027951. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27951.

Fallaize R, Dovey G, Woolf S. Prescription legibility: bigger might actually be better . Postgrad Med J . 2018;94(1117):617-620. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-136010.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Provider Identifier Standard (NPI) .

Drug Enforcement Administration. Prescriptions Q&A .

University of Minnesota. Prescription abbreviations .

Minnesota.gov. Partial list of prescription abbreviations .

American Medical Association. Patient rights .

By Michael Bihari, MD Michael Bihari, MD, is a board-certified pediatrician, health educator, and medical writer, and president emeritus of the Community Health Center of Cape Cod.

Getting clear on the new coding rules can help you eliminate bloated documentation and improve reimbursement to reflect the value of your visits.

THOMAS WEIDA, MD, FAAFP, AND JANE WEIDA, MD, FAAFP

Fam Pract Manag. 2022;29(1):26-31

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

In 2021, significant changes were adopted for the documentation guidelines for outpatient evaluation and management (E/M) visit codes. Most notably, medical decision making or time became primary drivers of visit level selection, rather than the number of history and physical exam bullets.

In this article, we review the context for these changes, describe them briefly, and offer a quick reference tool to help physicians apply the new rules in practice.

The revisions to the E/M outpatient visit codes reduced administrative burden by eliminating bullet points for the history and physical exam elements.

Code level selection is now simplified — based on either medical decision making or total time.

The authors' one-page coding reference tool can help simplify the new rules.

HOW WE GOT HERE

In the 2019 Medicare physician fee schedule final rule, released in November 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) adopted revisions to the outpatient E/M codes in order to reduce administrative burden. (See https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/final-policy-payment-and-quality-provisions-changes-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-calendar-year .) Originally scheduled for implementation in 2021, these changes would have combined visit levels 2–4 into a blended payment rate (e.g., one rate for 99202-99204 and one rate for 99212-99214), among other changes.

In response, the American Medical Association (AMA) convened a joint CPT Editorial Board and Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC) workgroup to build on the changes and propose some alternatives. The workgroup's goals were to decrease administrative burden, payer audits, and unnecessary medical record documentation while ensuring that payment of E/M services is resource-based.

The workgroup approved significant revisions to the outpatient office visit E/M codes. Code 99201 was deleted. The history and/or physical examination and the counting of bullets were eliminated as components for code selection (although history and/or physical examination documentation should still be performed as medically appropriate). Medical decision making (MDM) or time could be used for code level selection. Changes were made to the code descriptors for 99202-99205 and 99211-99215, the definition of medical decision making, and the calculation of time, and a shorter prolonged services add-on code was created. CMS adopted these new E/M coding guidelines. As a result of the changes to medical decision making and time-based coding, the RUC revised the 2021 relative value units (RVUs) for office visit E/M codes. Most of the values increased, yielding an overall increase of more than 10%.

CODING BASED ON MEDICAL DECISION MAKING

For outpatient E/M coding, medical decision making now has three components:

Number and complexity of problems addressed at the encounter,

Amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed,

Risk of complications and/or morbidity or mortality of patient management.

There are four levels of decision making for each of these components: straightforward, low complexity, moderate complexity, and high complexity.

To determine the level of code for a visit, two of the three components must meet or exceed that level of coding. ( See the table .) For example, if the patient has multiple problems addressed at the encounter, but the data is limited and the risk of complications is low, then the level of medical decision making would be low. New patient codes 99202-99205 and established patient codes 99212-99215 use the same components and levels of decision making for code selection.

Determining medical decision making usually starts with identifying the number and complexity of problems addressed and then determining the data or risk components that support that medical decision making. If a second component does not meet or exceed the problem component, then a lower level of decision making is appropriate. The set of tables below illustrate the essential concepts of these code levels. Each level has specific criteria for each component.

Straightforward medical decision making: Codes 99202 and 99212 include one self-limited or minor problem with minimal or no data and minimal risk.

An example of a 99202 or 99212 is an otherwise healthy patient with cough and congestion due to the common cold.

Low complexity medical decision making: Codes 99203 and 99213 include two or more self-limited or minor problems, one stable chronic illness, or one acute uncomplicated illness or injury.

The data component requires one of two categories to establish the level. Category 1 data requires at least two items in any combination of the following: each unique source's prior external notes reviewed, each unique test result reviewed, or each unique test ordered. Tests include imaging, laboratory, psychometric, or physiologic data. A clinical lab panel, such as a complete blood count, is a single test. Of note, if a test is ordered, the review of that test is included with the ordering, even if the review is done at a subsequent visit. Tests ordered outside of an encounter may be counted in the encounter in which they are analyzed. Category 2 data includes significant history given by an independent historian. Parents giving the history for their child is a typical example.

The risk component is low. There is low risk of morbidity from additional diagnostic testing or treatment.

An example of a 99203 or 99213 is a sinus infection treated with an antibiotic. Although the prescription makes the risk component moderate, the one acute uncomplicated illness is a low-complexity problem, and there are no data points.

Moderate complexity medical decision making: Codes 99204 and 99214 include two or more stable chronic illnesses, one or more chronic illnesses with exacerbation, progression, or side effects of treatment, one undiagnosed new problem with uncertain prognosis, one acute illness with systemic symptoms, or one acute complicated injury. A patient who is not at a treatment goal, such as a patient with poorly controlled diabetes, is not stable. Systemic general symptoms such as fever or fatigue in a minor illness (e.g., a cold with fever) do not raise the complexity to moderate. More appropriate would be fever with pyelonephritis, pneumonitis, or colitis.

The data component requires one of three categories to establish the level. Category 1 data requires at least three items in any combination of the following: each unique source's prior external notes reviewed, each unique test result reviewed, each unique test ordered, or independent historian involvement. Physicians cannot count tests that they or someone of the same specialty and same group practice are interpreting and reporting separately (e.g., electrocardiogram, X-ray, or spirometry). Category 2 data includes the independent interpretation of a test performed by another physician/other qualified health care professional (QHP) (not separately reported). For instance, if a chest X-ray was ordered and the ordering clinician included the interpretation in the visit documentation, this would qualify for data point Category 2. However, if the ordering clinician bills separately for the interpretation of the X-ray, then that cannot be used as an element in this category and would be an element for Category 1. Category 3 data includes discussion of management or test interpretation with an external physician/QHP (not separately reported).

The risk component may include prescription drug management, a decision for minor surgery with patient or procedure risk factors, a decision for elective major surgery without patient or procedure risk factors, or social determinants of health (SDOH) that significantly limit diagnostic or treatment options, such as food or housing insecurity. For prescription drug management, renewing pre-existing chronic medications would qualify. Documentation that the physician is managing the patient for the condition for which the medications are being prescribed would help establish validity in the use of this criterion for MDM.

An example of a 99204 or 99214 is a patient being seen for follow-up of hypertension and diabetes, which are well-controlled. An example using SDOH would be a patient with chronic knee pain and a positive anterior drawer test who needs imaging of the knee but cannot afford this care. Documenting that the patient cannot afford to obtain an MRI of the knee at this time, which significantly limits your ability to confirm the diagnosis and recommend treatment, adds to the risk component.

High complexity medical decision making: Codes 99205 and 99215 include one or more chronic illnesses with a severe exacerbation, progression, or side effects of treatment, or one acute or chronic illness or injury that poses a threat to life or bodily function.

The data component requires two of three categories to establish the level. These data categories are the same as those for 99204 and 99214, and they follow the same rules.

The risk component may include drug therapy requiring intensive monitoring for toxicity. Decisions regarding elective major surgery with patient or procedure risk, emergency major surgery, hospitalization, or “do not resuscitate” orders are also high risk. Intensive prescription drug monitoring is typically supported by a laboratory test, physiologic test, or imaging, and is done to evaluate for complications of the treatment. It may be short-term or long-term. Long-term monitoring is at least quarterly. An example would be monitoring for cytopenia during antineoplastic therapy. Monitoring the therapeutic effect of a treatment, such as glucose monitoring during insulin therapy, is not considered intensive prescription drug monitoring.

An example of a 99205 or 99215 is a patient with severe exacerbation of chronic heart failure who is admitted to the hospital.

CODING OUTPATIENT E/M VISITS

Time-based coding.

An alternative method to determine the appropriate visit level is time-based coding. A major change is that total time now includes both face-to-face and non-face-to-face services personally performed by the physician/QHP on the day of the visit. Additionally, time-based coding is no longer restricted to counseling services. Instead, it includes the following:

Preparing to see the patient (e.g., reviewing external test results),

Obtaining and/or reviewing separately obtained history,

Performing a medically appropriate examination and/or evaluation,

Counseling and educating the patient, family, or caregiver,

Ordering medications, tests, or procedures,

Referring and communicating with other health care professionals (when not separately reported),

Documenting clinical information in the electronic or other health record,

Independently interpreting results (not separately reported with a CPT code) and communicating results to the patient, family, or caregiver.

Care coordination (not separately reported with a CPT code).

Time spent by clinical staff cannot count toward total time. However, time spent by another physician/QHP (not a resident physician) in the same group can be included. If a nurse practitioner performs the initial intake and the physician provides the assessment and plan, both of those times can be counted, although only one person's time can be counted while they are discussing the case with each other. The visit should be billed under the clinician who provided the substantive portion (more than half) of the time, although both clinicians need to be identified in the medical record. Time spent must be documented in the note. It is advisable to specifically document the time spent and the activities performed both face-to-face and non-face-to-face.

The amount of total time required for each level of coding changed under the new time-based coding guidelines. (See the “Total time ” table.)

PROLONGED VISIT CODES

When time on the date of service extends beyond the times for codes 99205 or 99215, prolonged visit codes can be used. The AMA CPT committee developed code 99417 for prolonged visits, and Medicare developed code G2212. These are added in 15-minute increments in addition to codes 99205 or 99215. Code G2212 can be added once the maximum time for 99205 or 99215 has been surpassed by a full 15 minutes, whereas code 99417 can be added once the minimum time for 99205 or 99215 has been surpassed by a full 15 minutes. Less than 15 minutes is not reportable. Multiple units can be reported. Prolonged visit codes cannot be used with the shorter E/M levels, i.e., 99202-99204 and 99212-99214. (See “Prolonged services ” tables.) Clinicians should consult with individual payers to determine which code to use — G2212 or 99417.

SIMPLIFIED CODING AND DOCUMENTATION

The revisions to the outpatient E/M visit codes reduced administrative burden by eliminating bullet points for the history and physical exam elements. Only medically appropriate documentation is required. Code level selection is simplified — based on either medical decision making or total time. By applying these changes, primary care clinicians can eliminate bloated documentation and improve reimbursement reflecting the value of the visit.

Continue Reading

More in FPM

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2022 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

BREAKING: Sean 'Diddy' Combs has been arrested

Cut up and leased out, the bodies of the poor suffer a final indignity in Texas

The University of North Texas Health Science Center built a flourishing business using hundreds of unclaimed corpses. It suspended the program after NBC News exposed failures to treat the dead and their families with respect.

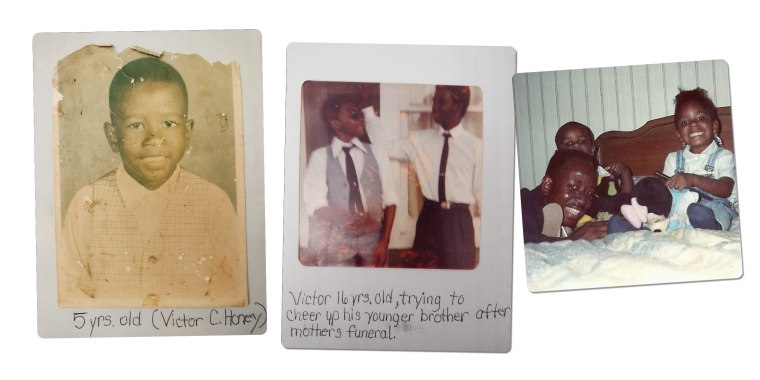

DALLAS — Long before his bleak final years, when he struggled with mental illness and lived mostly on the streets, Victor Carl Honey joined the Army, serving honorably for nearly a decade. And so, when his heart gave out and he died alone 30 years later, he was entitled to a burial with military honors.

Instead, without his consent or his family’s knowledge, the Dallas County Medical Examiner’s Office gave his body to a state medical school, where it was frozen, cut into pieces and leased out across the country.

A Swedish medical device maker paid $341 for access to Honey’s severed right leg to train clinicians to harvest veins using its surgical tool. A medical education company spent $900 to send his torso to Pittsburgh so trainees could practice implanting a spine stimulator. And the U.S. Army paid $210 to use a pair of bones from his skull to educate military medical personnel at a hospital near San Antonio.

In the name of scientific advancement, clinical education and fiscal expediency, the bodies of the destitute in the Dallas-Fort Worth region have been routinely collected from hospital beds, nursing homes and homeless encampments and used for training or research without their consent — and often without the approval of any survivors, an NBC News investigation found.

Honey, who died in September 2022, is one of about 2,350 people whose unclaimed bodies have been given to the Fort Worth-based University of North Texas Health Science Center since 2019 under agreements with Dallas and Tarrant counties . Among these, more than 830 bodies were selected by the center for dissection and study. After the medical school and other groups were finished, the bodies were cremated and, in most cases, interred at area cemeteries or scattered at sea. Some had families who were looking for them.

For months as NBC News reported this article, Health Science Center officials defended their practices, arguing that using unclaimed bodies was essential for training future doctors. But on Friday, after reporters shared detailed findings of this investigation, the center announced it was immediately suspending its body donation program and firing the officials who led it. The center said it was also hiring a consulting firm to investigate the program’s operations.

“As a result of the information brought to light through your inquiries, it has become clear that failures existed in the management and oversight of The University of North Texas Health Science Center’s Willed Body Program,” the statement said. “The program has fallen short of the standards of respect, care and professionalism that we demand.”

Last year, NBC News revealed in its “Lost Rites” investigation that coroners and medical examiners in Mississippi and nationally had repeatedly failed to notify families of their loved ones’ deaths before burying them in pauper’s graveyards . That investigation led reporters to North Texas, where officials had come to view the unclaimed dead not as a costly burden, but as a free resource.

Before its sudden shuttering last week, the Health Science Center’s body business flourished.

On paper, the arrangements with Dallas and Tarrant counties offered a pragmatic solution to an expensive problem: Local medical examiners and coroners nationwide bear the considerable costs of burying or cremating tens of thousands of unclaimed bodies each year. Disproportionately Black, male, mentally ill and homeless, these are individuals whose family members often cannot be easily reached, or whose relatives cannot or will not pay for cremation or burial.

The University of North Texas Health Science Center used some of these bodies to teach medical students. Others, like Honey’s, were parceled out to for-profit medical training and technology companies — including industry giants like Johnson & Johnson, Boston Scientific and Medtronic — that rely on human remains to develop products and teach doctors how to use them. The Health Science Center advertised the bodies as being of “the highest quality found anywhere in the U.S.”

Do you have a story to share about the use of unclaimed bodies for research? Contact us .

Proponents say using unclaimed bodies transforms a tragic situation into one of hope and service, providing a steady supply of human specimens needed to educate doctors and advance medical research. But for families who later discover their missing relatives were dissected and studied, the news is haunting, compounding their grief and depriving them of the opportunity to mourn.

“The county and the medical school are doing this because it saves them money, but that doesn’t make it right,” said Thomas Champney, an anatomy professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine who researches the ethical use of human bodies . “Since these individuals did not consent, they should not be used in any form or fashion.”

A half-century ago, it was common for U.S. medical schools to use unclaimed bodies, and doing so remains legal in most of the country, including Texas. Many programs have halted the practice in recent years, though, and some states, including Hawaii, Minnesota and Vermont, have flatly prohibited it — part of an evolution of medical ethics that has called on anatomists to treat human specimens with the same dignity shown to living patients.

The University of North Texas Health Science Center charged in the opposite direction.

Through public records requests, NBC News obtained thousands of pages of government records and data documenting the acquisition, dissection and distribution of unclaimed bodies by the center over a five-year period.

An analysis of the material reveals repeated failures by death investigators in Dallas and Tarrant counties — and by the center — to contact family members who were reachable before declaring a body unclaimed. Reporters examined dozens of cases and identified 12 in which families learned weeks, months or years later that a relative had been provided to the medical school, leaving many survivors angry and traumatized.

Five of those families found out what happened from NBC News. Reporters used public records databases, ancestry websites and social media searches to locate and reach them within just a few days, even though county and center officials said they had been unable to find any survivors.

In one case, a man learned of his stepmother’s death and transfer to the center after a real estate agent called about selling her house. In another, Dallas County marked a man’s body as unclaimed and gave it to the Health Science Center, even as his loved ones filed a missing person report and actively searched for him.

From 2023: NBC News’ “Lost Rites” investigation

- After a mother in Jackson, Mississippi, reported her son missing, police kept the truth from her for months.

- ‘They just threw him away’: Another Mississippi man was buried without his family’s knowledge .

- America’s patchwork death notification system routinely leaves families in the dark.

- The Department of Justice took action after a Mississippi coroner buried men without notifying their families.

- The Jackson Police Department adopted a next-of-kin notification policy following NBC News’ reporting.

Before the Health Science Center announced it was suspending the program, officials in the two counties had already told NBC News they were reconsidering their unclaimed body agreements in light of the reporters’ findings.

Commissioners in Dallas County recently postponed a vote on whether to extend their contract. The top elected official in Tarrant County, Judge Tim O’Hare — who voted to renew the county’s agreement with the center in January — said he planned to explore legal options “to end any and all immoral, unethical, and irresponsible practices stemming from this program.”

“No individual’s remains should be used for medical research, nor sold for profit, without their pre-death consent, or the consent of their next of kin,” O’Hare’s office said . “The idea that families may be unaware that their loved ones’ remains are being used for research without consent is disturbing, to say the least.”

NBC News also shared its findings with dozens of companies, teaching hospitals and medical schools that have relied on the Health Science Center to supply human specimens. Ten said they did not know the center had provided them with unclaimed bodies. Some, including Medtronic, said they had internal policies requiring consent from the deceased or their legal surrogate.

DePuy Synthes, a Johnson & Johnson company, said it had paused its relationship with the center after learning from a reporter that it had received body parts from four unclaimed people. And Boston Scientific, whose company Relievant Medsystems used the torsos of more than two dozen unclaimed bodies for training on a surgical tool , said it was reviewing its transactions with the center, adding that it had believed the program obtained consent from donors or families.

“We empathize with the families who were not reached as part of this process,” the company said.

The Army said it, too, was examining its reliance on the center and planned to review and clarify internal policies on the use of unclaimed bodies. Under federal contracts totaling about $345,000, the center has provided the Army with dozens of whole bodies, heads and skull bones since 2021 — including at least 21 unclaimed bodies. An Army spokesperson said officials had not considered the possibility that the program hadn’t gotten consent from donors or their families.

The Texas Funeral Service Commission, which regulates body donation programs in the state, is conducting a review of its own. In April, the agency issued a moratorium on out-of-state shipments while it studies a range of issues, including the use of unclaimed bodies by the Health Science Center.

In the case of Victor Honey, it shouldn’t have been hard for Dallas County investigators to find survivors: His son shares his father’s first and last name and lives in the Dallas area. Family members are outraged that no one from the county or the Health Science Center informed them of Honey’s death, much less sought permission to dissect his body and distribute it for training.