Founder of Journey Life Tv, Dr. Joesph L. Williams is a pastor, speaker, author, life coach, community activist, and a certified nutritionist and holistically trained doctor.

Step One: Journey Book

Step two: 40 day turn up.

Step Three: Journey 3.0

Journey 3.0 is invite only. You must be a graduate of the 40 Day Turn Up to progress to this level.

KEEP IN TOUCH WITH US FOR OUR LATEST NEWS

- Full Name * First Name Last Name

- First & Last Name *

- Ethniticity *

- Best Contact number *

Ep. 15- “Rampant Rachetness and The Need for Authentic Spirituality”

In this episode, Dr. Joseph L. Williams discusses:

Tune in so you can learn more about “The Journey Life with Dr. Joe!”

If you desire to ask a question for a future episode, please send your question to [email protected]

Ep. 14- “Soul Ties-Pt. 2”

Ep. 13- “soul ties-do i have one”, ep. 12- “emotional baggage-how to let go”.

This is the twelfth episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

Ep. 11- “Emotional Eating”

This is the eleventh episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

Ep. 10- “HIV/AIDS-Is There A Cure?”

This is the tenth episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

Ep. 009- “Gaining Weight with Age”

This is the ninth episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

Ep. 008 – “Bread, wheat and grans could make you sick!”

This is the eighth episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

Ep. 007 – “5 Things you DON’T need to lose weight or remain healthy”

This is the seventh episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

Ep. 006 – “Q&A with Dr. Joe”

This is the sixth episode of “Journey Life” podcast.

- 3 Questions asked by listeners!

Dr. Williams answers key questions submitted by listeners. Tune in so you can learn more about “The Journey Life with Dr. Joe!”

Dr. Joe’s Detox TM Juices

***DISCLAIMER: Please get approval from your MD before purchasing and consuming “Doctor Joe’s Detox.” Also note, the purchase of “Doctor Joe’s Detox” does not come with nutritional counseling or a food plan of any kind.***

PLEASE NOTE

APPLE CRANBERRY

16 oz @ $10.00 USD

$ 10.00 QTY. Apple Cranberry quantity Add to cart

INGREDIENTS : Clarified Pear Juice Concentrate, White Grape Juice Concentrate, Water, Natural and Artificial Flavors, Citric Acid, Sodium Benzoate & Potassium Sorbate As Preservatives, Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C), FD&C Red # 40.

ORANGE PINEAPPLE

$ 10.00 QTY. Orange Pineapple quantity Add to cart

INGREDIENTS: Clarified Pear Juice Concentrate, White Grape Juice Concentrate, Water, Natural and Artificial Flavors, Citric Acid, Sodium Benzoate & Potassium Sorbate As Preservatives, Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C), FD&C Yellow # 6.

$ 10.00 QTY. Very Berry quantity Add to cart

INGREDIENTS: Clarified Pear Juice Concentrate, White Grape Juice Concentrate, Water, Natural and Artificial Flavors, Citric Acid, Sodium Benzoate & Potassium Sorbate As Preservatives, Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C).

STRAWBERRY KIWI

$ 10.00 QTY. Strawberry Kiwi quantity Add to cart

FRUIT PUNCH

$ 10.00 QTY. Out of stock

DR. JOE’S DEVOTIONAL

$ 20.00 QTY.

$ 20.00 QTY. Out of stock

The Journey devotional is a Devotional specifically written for those who are matriculating through any process with “40 Days with Dr Joe.” The journal provides daily (40 Days) scriptures, lessons, points of reflection, daily challenges as well as a place for each participants daily journal entry. The design is to help each participant remain focused and get the results they desire

DR. JOE’S JUICE TM IS CONCENTRATED

Our 16 ounce bottle makes 1 gallon of juice.

SHIP ORDERS

DUE TO COVID-19 OUR DELIVERY SCHEDULE HAS BEEN DELAYED. PLEASE NOTE ORDERS TAKE 5 TO 7 BUSINESS DAYS FOR PROCESSING AND 3 TO 4 ADDITIONAL DAYS FOR DELIVERY. PLEASE ALLOW FOR THESE SHIPPING FACTORS PRIOR TO ORDERING.

Where Is Charles Bridgeman From 'My 600-lb Life' Now? He's Lost a Significant Amount of Weight

While Charles qualified for weight loss surgery, he declined the offer, claiming he didn't want to move to Houston and leave his family.

Apr. 17 2024, Published 8:01 p.m. ET

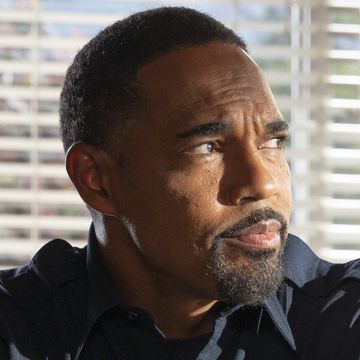

TLC's My 600-lb Life highlights the weight loss attempts of severely obese individuals across the country as they work with esteemed bariatric surgeon Dr. Now .

The individuals the show features all have one thing in common: They're addicted to food and the feeling it gives them.

During the Season 12 finale, we meet Charles Bridgeman from Everett, Wash., who knows all about grappling with a life-threatening addiction. While food was always a comfort for him, he was addicted to meth for a decade. His addiction prompted his mom and grandma to kick him out, leaving him homeless for quite some time and even resulting in him getting arrested.

Fortunately, Charles went to rehab and got clean a few years back. But this shining achievement was eclipsed by the fact that he seemed to have replaced drugs with food.

When we meet Charles, who is in his early 30s, he is living with his brother, Brad, and sister, Cheyana. Brad's full-time job has become taking care of Charles, who cannot make himself food and can only walk a few steps at a time before needing to rest.

Charles's journey on My 600-lb Life was an interesting one. He and Dr. Now butted heads several times and Charles often didn't follow Dr. Now's directions. Usually, when this happens on the show, the individual ends up gaining weight and getting farther away from their goal.

However, Charles did lose weight, and Dr. Now did end up approving him for weight loss surgery. But Charles had seemingly gotten so comfortable at home with Brad, who kept him on track, that he declined the offer. He said didn't want to move to Houston for the surgery and leave his family, even if it was only temporary.

At the end of the episode, Charles said he wanted to continue his weight loss efforts in Everett and possibly reconsider surgery in the future. That said, where is Charles now? Did he ever get bariatric surgery, and was he able to continue losing weight on his own?

Charles and his brother Brad in Dr. Now's office in Houston, Texas

Where is Charles Bridgeman from 'My 600-lb Life' now?

Since his time on My 600-lb Life , Charles appears to be doing very well. According to his Facebook profile , he is still living in Everett, Wash., and has continued to lose weight.

Charles has been spending time with his dogs and recently took them to the dog park, illustrating that he's still making an effort to go outside and do more activities.

However, the biggest update is Charles's current weight. At the beginning of his episode, he was believed to be over 700 pounds. After adopting Dr. Now's diet plan and developing an exercise routine, he was down to 604 pounds by the end of the episode, losing well over 100 pounds on his journey.

Omg down to 385 Posted by Charles Bridgeman on Wednesday, September 27, 2023

That being said, in September 2023, Charles revealed some exciting news: "Omg down to 385," he wrote on Facebook.

It's unclear if this substantial weight loss was strictly from dieting or if Charles did get bariatric surgery, which would likely expedite his weight loss. However, we are glad to hear that Charles hasn't given up and is continuing to lose weight.

Where Is Shakyia Jackson From 'My 600-lb Life' Now? She Appears to Have Started Her Own Business

Where Is Abi Ruiz From 'My 600-lb Life' Now? An Update on His Health

William Keefer From 'My 600-lb Life Now' Season 12 Struggled to Follow a Diet — Where Is He Now?

Latest My 600-lb Life News and Updates

- ABOUT Distractify

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- CONNECT with Distractify

- Link to Facebook

- Link to Instagram

- Contact us by Email

Opt-out of personalized ads

© Copyright 2024 Distractify. Distractify is a registered trademark. All Rights Reserved. People may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website. Offers may be subject to change without notice.

‘My 600-lb Life’ Season 12, episode 6: How to watch TLC online for free

- Updated: Apr. 17, 2024, 2:30 p.m. |

- Published: Apr. 17, 2024, 2:30 p.m.

Rose's Journey, My 600 lb. Life (Image courtesy TLC) tlc

- Yadi Rodriguez, cleveland.com

“ My 600-lb. Life ” Season 12 continues tonight, Wednesday, April 17, at 8 p.m. Eastern on TLC , with the season’s sixth episode.

If you’ve cut the cord but still want to tune in, you can watch the show for free on Philo , FuboTV and DirecTV Stream ; each of these services offers a free trial to new subscribers. Also, Sling offers promotions for new customers.

In tonight’s show, titled “Charles’s Journey,” we meet Charles, who quit hard drugs and replaced that addiction with food. He can’t stop eating and now has a BMI over 100. Since his brother does everything for him, is he motivated and ready to head to Houston and get Dr. Now’s assistance?

Did you miss the last episode ? You can catch up and watch it before the new episode airs tonight.

What streaming services carry TLC?

FuboTV offers access to over 100 entertainment, news and sports channels for $74.99/month after the free trial ends. Philo offers over 70 channels for $25/month after the free trial ends. DirecTV Stream offers 75+ channels for $74.99 after the free trial, and Sling offers the channel as part of its Blue package ($40 monthly after the first month).

Cable Guide: What channel is TLC on?

You can find which channel TLC is on by using the channel finders here: Cox , Verizon Fios , AT&T U-verse , Comcast Xfinity , Spectrum/Charter , Optimum/Altice , DIRECTV and Dish .

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

From the Heisman to white Bronco chase and murder trial: A timeline of O.J. Simpson's life

Once the most high-profile celebrity in the country, O.J. Simpson died Wednesday at the age of 76.

The California native lived a life consistently in the spotlight, whether it was his football career , his acting career or a murder accusation and trial that captivated the nation. Simpson was one of the most polarizing figures in the country and seemed to always be in the news, all the way up to his death on Wednesday.

"During this time of transition, his family asks that you please respect their wishes for privacy and grace," his family said in a statement on social media.

Here is a timeline of the biggest moments from Simpson's life:

When was O.J. Simpson born?

Simpson was born on July 9, 1947.

NFL DRAFT HUB: Latest NFL Draft mock drafts, news, live picks, grades and analysis.

Where was O.J. Simpson born?

Simpson was born and raised in San Francisco, California.

Start of O.J. Simpson's football career

With Simpson still in the San Francisco area, he attended Galileo High School, where he was a star running back, defensive back and track athlete. After graduating in 1965, he started his college career at City College of San Francisco. There, he was named a junior college All-American as a running back in 1966. Simpson transferred to Southern California after two seasons.

O.J. Simpson wins Heisman Trophy

Simpson became an instant star for the Trojans. During his first season with Southern California, he led the nation with 1,543 rushing yards and scored 13 touchdowns to help lead USC to a national championship. He finished second in the Heisman Trophy race to UCLA quarterback Gary Beban.

His senior season in 1968, Simpson continued to lead USC as he ran for a then NCAA-record 1,709 yards and 22 touchdowns. Simpson won the 1968 Heisman Trophy by 1,750 points, a record margin at the time. To this day, his 855 first-place votes are the most in Heisman Trophy history. By the end of his college career, Simpson equaled or broke 19 NCAA, Pac-8 and USC records.

O.J. Simpson's first marriage

Simpson married Marguerite Whitley in 1967, and they had three children: Arnelle Simpson, Jason Simpson and Aaren Simpson. In 1979, one-year-old Aaren drowned in the family's swimming pool. Simpson and Whitley divorced in 1979.

O.J. Simpson is No. 1 pick in NFL Draft

With such a stellar college career, Simpson was the easy choice in the 1969 AFL-NFL Draft. He was the No. 1 overall pick by the Buffalo Bills.

O.J. Simpson breaks NFL rushing record

Simpson had a mediocre start to his NFL career, but he really broke out in his fourth season in 1972, when the Bills hired Lou Saban as head coach. That season, Simpson led the NFL in rushing yards with 1,251.

His legendary season came in 1973. On Dec. 16, 1973, Simpson ran for 200 yards against the New York Jets at Shea Stadium to become the first player in NFL history to rush for 2,000 yards in a single season − he finished with 2,003 rushing yards. His 143.1 rushing yards per game that season is still the highest mark in NFL history, and he was named league MVP that season.

O.J. Simpson retires

Simpson ran for more than 1,000 yards in the three seasons after his MVP year, but in 1978, Buffalo traded him to the San Francisco 49ers. Simpson wasn't a star for San Francisco, and he played two seasons for the 49ers before retiring in 1979 after a decade in the league.

He finished his career with 11,236 rushing yards, 2,142 receiving yards and 990 kick return yards. Simpson totaled 76 career touchdowns.

O.J. Simpson acting career

A football career didn't stop Simpson from becoming an actor , getting roles as early as 1968, the same year he won the Heisman. He appeared in several movies and TV shows, but his most memorable role was as Detective Nordberg in the "Naked Gun" comedy films, opposite star Leslie Nielsen. Simpson appeared in all three movies from 1988 to 1994.

Simpson also appeared in Hertz commercials and hosted Saturday Night Live in 1978. During this time, he also worked as a commentator on "Monday Night Football" and NFL games on NBC.

Documentary: How to watch FX’s 'The People v. O.J. Simpson' and ESPN’s 'O.J. Made in America'

O.J. Simpson inducted into Pro Football Hall of Fame

Simpson was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1985, his first year of eligibility. During his enshrinement speech, Simpson thanked all of the people that were part of his football journey.

"I want to thank God for when I think about history and all the great people for allowing me to live at a time when such basic talents of body functions as running and jumping would be worthy of applause," Simpson said in his speech. " I just want all the fans in the NFL to know how much I appreciate it. No matter what stadium I would play in, you cheered me and made me feel appreciated and welcome. And I want to tell you that I know now already in my heart and in my memories the things that I will miss the most about this game is the sound of your applause and your cheers."

O.J. Simpson marries Nicole Brown

Simpson met Nicole Brown in the late 1970s and they were married in 1985. The couple had two children and were married for seven years before they were divorced in 1992.

Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman found dead

On June 12, Brown and friend Ron Goldman were found stabbed to death in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles. Simpson had a domestic violence charge against Brown during their marriage and he was immediately a person of interest in the deaths.

O.J. Simpson police chase

Charges were pressed against Simpson and a warrant was issued for his arrest for the death of Brown and Goldman. Simpson planned to turn himself in, but instead led a low-speed car chase on June 17, 1994 that was televised with millions of viewers tuning in to see one of the most infamous moments of television history .

More: What happened to white Ford Bronco in O.J. Simpson car chase?

O.J. Simpson trial

With Simpson charged as the suspect in the murder of Brown and Goldman, his trial took place in 1995 and was dubbed the "Trial of the Century" as it was televised. People involved in the case, from the prosecutors to the judge, became celebrities.

With its coverage, the case had some of the biggest moments to ever happen in court, including when Simpson struggled to put his hand inside of the bloody glove found at the scene of the crime. One of Simpson's attorneys, the famous Johnnie Cochran, uttered a now-infamous phrase, "If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit."

More: Late Johnnie Cochran's firm prays families find 'measure of peace' after O.J. Simpson's death

O.J. Simpson found not guilty of murder

After nearly a year in court, the jury reached a verdict in Simpson's trial. On October 3, 1995, the jury found Simpson "not guilty" of the two murders, a decision applauded and ridiculed across the country. No one was ever arrest for the murders, but Simpson was found liable in a wrongful death lawsuit. He was ordered to pay millions of dollars to both families.

'If I Did It'

A book was released in 2007 titled "If I Did It: Confessions of the Killer," which supposedly detailed through an interview with a ghost writer − how Simpson would have killed Brown and Goldman. There was much controversy surrounding the release of the book, and the Goldman family was awarded the rights to book.

O.J. Simpson robbery, prison sentence

In 2007, Simpson and a group of people went into a room at Palace Station in Las Vegas, where he and others took memorabilia that he alleged was stolen from him at gunpoint.

He was arrested days afterward for his involvement, and his trial took place in 2008. In court, Simpson was found guilty of several counts and was sentence to 33 years in prison with the possibility of parole after nine years (2017). Simpson served his sentence at Lovelock Correctional Center in Nevada.

O.J. Simpson release from prison

In 2017, Simpson was granted parole from his prison sentence and was released from prison on Oct. 1, 2017. In December 2021, Simpson was released from his parole.

O.J. Simpson cancer diagnosis, death

Simpson's family said he succumbed to a cancer diagnosis April 10. The Pro Football Hall of Fame said Simpson had prostate cancer and he received chemotherapy treatment.

Simpson’s diagnosis of prostate cancer was made public about two months ago, and he had received chemotherapy treatment.

- Share full article

For more audio journalism and storytelling, download New York Times Audio , a new iOS app available for news subscribers.

The Supreme Court Takes Up Homelessness

Can cities make it illegal to live on the streets.

This transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors. Please review the episode audio before quoting from this transcript and email [email protected] with any questions.

From “The New York Times,” I’m Katrin Bennhold. This is “The Daily.”

This morning, we’re taking a much closer look at homelessness in the United States as it reaches a level not seen in the modern era. California —

As the number of homeless people has surged in the US —

More than 653,000, a 12 percent population increase since last year.

The debate over homeless encampments across the country has intensified.

It is not humane to let people live on our streets in tents, use drugs. We are not standing for it anymore.

People have had it. They’re fed up. I’m fed up. People want to see these tents and encampments removed in a compassionate, thoughtful way. And we agree.

With public officials saying they need more tools to address the crisis.

We move from block to block. And every block they say, can’t be here, can’t be here, can’t be here. I don’t know where we’re supposed to go, you know?

And homeless people and their advocates saying those tools are intended to unfairly punish them.

They come and they sweep and they take everything from me, and I can’t get out of the hole I’m in because they keep putting me back in square one.

That debate is now reaching the Supreme Court, which is about to hear arguments in the most significant case on homelessness in decades, about whether cities can make it illegal to be homeless. My colleague Abbie VanSickle on the backstory of that case and its far-reaching implications for cities across the US.

[THEME MUSIC]

It’s Friday, April 19.

So Abbie, you’ve been reporting on this case that has been making waves, Grants Pass versus Johnson, which the Supreme Court is taking up next week. What’s this case about?

So this case is about a small town in Oregon where three homeless people sued the city after they received tickets for sleeping and camping outside. And this case is the latest case that shows this growing tension, especially in states in the West, between people who are homeless and cities who are trying to figure out what to do about this. These cities have seen a sharp increase in homeless encampments in public spaces, especially with people on sidewalks and in parks. And they’ve raised questions about public drug use and other safety issues in these spaces.

And so the question before the justices is really how far a city can go to police homelessness. Can city officials and police use local laws to ban people from laying down outside and sleeping in a public space? Can a city essentially make it illegal to be homeless?

So three homeless people sued the city of Grants Pass, saying it’s not illegal to be homeless, and therefore it’s not illegal to sleep in a public space.

Yes, that’s right. And they weren’t the first people to make this argument. The issue actually started years ago with a case about 500 miles to the East, in Boise, Idaho. And in that case, which is called Martin v. Boise, this man, Robert Martin, who is homeless in Boise, he was charged with a misdemeanor for sleeping in some bushes. And the city of Boise had laws on the books to prohibit public camping.

And Robert Martin and a group of other people who are homeless in the city, they sued the city. And they claimed that the city’s laws violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment.

And what makes it cruel and unusual?

So their argument was that the city did not have enough sufficient shelter beds for everyone who was homeless in the city. And so they were forced to sleep outside. They said, we have no place to go and that an essential human need is to sleep and we want to be able to lay down on the sidewalk or in an alley or someplace to rest and that their local laws were a violation of Robert Martin and the others’ constitutional rights, that the city is violating the Eighth Amendment by criminalizing the human need to sleep.

And the courts who heard the case agreed with that argument. The courts ruled that the city had violated the Constitution and that the city could not punish people for being involuntarily homeless. And what that meant, the court laid out, is that someone is involuntarily homeless if a city does not have enough adequate shelter beds for the number of people who are homeless in the city.

It does seem like a very important distinction. They’re saying, basically, if you have nowhere else to go, you can’t be punished for sleeping on the street.

Right. That’s what the court was saying in the Martin v. Boise case. And the city of Boise then appealed the case. They asked the Supreme Court to step in and take it on. But the Supreme Court declined to hear the case. So since then, the Martin v. Boise case controls all over the Western parts of the US in what’s called the Ninth Circuit, which includes Oregon where the Grants Pass case originated.

OK. So tell us about Grants Pass, this city at the center of the case and now in front of the Supreme Court. What’s the story there?

Grants Pass is a town in rural Southwestern Oregon. It’s a town of about 38,000 people. It’s a former timber town that now really relies a lot on tourists to go rafting through the river and go wine tasting in the countryside. And it’s a pretty conservative town.

When I did interviews, people talked about having a very strong libertarian streak. And when I talked with people in the town, people said when they were growing up there, it was very rare to see someone who was homeless. It just was not an issue that was talked a lot about in the community. But it did become a big issue about 10 years ago.

People in the community started to get worried about what they saw as an increase in the number of homeless people that they were noticing around town. And it’s unclear whether the problem was growing or whether local officials and residents were worried that it might, whether they were fearing that it might.

But in any case, in 2013, the city council decided to start stepping up enforcement of local ordinances that did things like outlaw camping in public parks or sleeping outside, this series of overlapping local laws that would make it impossible for people to sleep in public spaces in Grants Pass. And at one meeting, one of the former city council members, she said, “the point is to make it uncomfortable enough for them in our city so they will want to move on down the road.”

So it sounds like, at least in Grants Pass, that this is not really about reducing homelessness. It’s about reducing the number of visible homeless people in the town.

Well, I would say that city officials and many local residents would say that the homeless encampments are actually creating real concerns about public safety, that it’s actually creating all kinds of issues for everyone else who lives in Grants Pass. And there are drug issues and mental health issues, and that this is actually bringing a lot of chaos to the city.

OK. So in order to deal with these concerns, you said that they decided to start enforcing these local measures. What does that actually look like on the ground?

So police started handing out tickets in Grants Pass. These were civil tickets, where people would get fines. And if police noticed people doing this enough times, then they could issue them a trespass from a park. And then that would give — for a certain number of days, somebody would be banned from the park. And if police caught them in the park before that time period was up, then the person could face criminal time. They could go to jail.

And homeless people started racking up fines, hundreds of dollars of fines. I talked to a lot of people who were camping in the parks who had racked up these fines over the years. And each one would have multiple tickets they had no way to pay. I talked to people who tried to challenge the tickets, and they had to leave their belongings back in the park. And they would come back to find someone had taken their stuff or their things had been impounded.

So it just seemed to be this cycle that actually was entrenching people more into homelessness. And yet at the same time, none of these people had left Grants Pass.

So they did make it very uncomfortable for homeless people, but it doesn’t seem to be working. People are not leaving.

Right. People are not leaving. And these tickets and fines, it’s something that people have been dealing with for years in Grants Pass. But in 2018, the Martin v. Boise case happens. And not long after that, a group of people in Grants Pass challenged these ordinances, and they used the Boise case to make their argument that just like in Boise, Grants Pass was punishing people for being involuntarily homeless, that this overlapping group of local ordinances in Grants Pass had made it so there is nowhere to put a pillow and blanket on the ground and sleep without being in some kind of violation of a rule. And this group of local homeless people make the argument that everyone in Grants Pass who is homeless is involuntarily homeless.

And you told us earlier that it was basically the lack of available shelter that makes a homeless person involuntarily homeless. So is there a homeless shelter in Grants Pass?

Well, it sort of depends on the standard that you’re using. So there is no public low-barrier shelter that is easy for somebody to just walk in and stay for a night if they need someplace to go. Grants Pass does not have a shelter like that.

There is one shelter in Grants Pass, but it’s a religious shelter, and there are lots of restrictions. I spoke with the head of the shelter who explained the purpose is really to get people back into the workforce. And so they have a 30-day program that’s really designed for that purpose.

And as part of that, people can’t have pets. People are not allowed to smoke. They’re required to attend Christian religious services. And some of the people who I interviewed, who had chronic mental health and physical disabilities, said that they had been turned away or weren’t able to stay there because of the level of needs that they have. And so if you come in with any kind of issue like that, it can be a problem.

That’s a very long list of restrictions. And of course, people are homeless for a lot of very different reasons. It sounds like a lot of these reasons might actually disqualify them from this particular shelter. So when they say they have nowhere else to go, if they’re in Grants Pass, they kind of have a point.

So that’s what the court decided. In 2022, when the courts heard this case, they agreed with the homeless plaintiffs that there’s no low-barrier shelter in Grants Pass and that the religious shelter did not meet the court’s requirements. But the city, who are actually now represented by the same lawyers who argued for Boise, keeps appealing the case. And they appeal up to the Ninth Circuit just as in the Boise case, and the judges there find in favor of the homeless plaintiffs, and they find that Grants Pass’s ordinances are so restrictive that there is no place where someone can lay down and sleep in Grants Pass and that therefore the city has violated the Eighth Amendment and they cannot enforce these ordinances in the way that they have been for years.

So at that point, the court upholds the Boise precedent, and we’re where we were when it all started. But as we know, that’s not the end of the story. Because this case stays in the court system. What happened?

So by this point, the homelessness problem is really exploding throughout the Western part of the US with more visible encampments, and it really becomes a politically divisive issue. And leaders across the political spectrum point to Boise as a root cause of the problem. So when Grants Pass comes along, people saw that case as a way potentially to undo Boise if only they could get it before the Supreme Court.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We’ll be right back.

Abbie, you just told us that as homeless numbers went up and these homeless encampments really started spreading, it’s no longer just conservatives who want the Supreme Court to revisit the Boise ruling. It’s liberals too.

That’s right. So there’s a really broad group of people who all started pushing for the Supreme Court to take up the Grants Pass case. And they did this by filing briefs to the Supreme Court, laying out their reasoning. And it’s everyone from the liberal governor of California and many progressive liberal cities to some of the most conservative legal groups. And they disagree about their reasoning, but they all are asking the court to clarify how to interpret the Boise decision.

They are saying, essentially, that the Boise decision has been understood in different ways in all different parts of the West and that that is causing confusion and creating all sorts of problems. And they’re blaming that on the Boise case.

It’s interesting, because after everything you told us about these very extreme measures, really, that the city of Grants Pass took against homeless people, it is surprising that these liberal bastions that you’re mentioning are siding with the town in this case.

Just to be clear, they are not saying that they support necessarily the way that Grants Pass or Boise had enforced their laws. But they are saying that the court rulings have tied their hands with this ambiguous decision on how to act.

And what exactly is so ambiguous about the Boise decision? Which if I remember correctly, simply said that if someone is involuntarily homeless, if they’re on the streets because there’s no adequate shelter space available, they can’t be punished for that.

Yeah. So there are a couple of things that are common threads in the cities and the groups that are asking for clarity from the court. And the first thing is that they’re saying, what is adequate shelter? That every homeless person situation is different, so what are cities or places required to provide for people who are homeless? What is the standard that they need to meet?

In order not to sleep on the street.

That’s right. So if the standard is that a city has to have enough beds for everyone who is homeless but certain kinds of shelters or beds wouldn’t qualify, then what are the rules around that? And the second thing is that they’re asking for clarity around what “involuntarily homeless” means. And so in the Boise decision, that meant that someone is involuntarily homeless if there is not enough bed space for them to go to.

But a lot of cities are saying, what about people who don’t want to go into a shelter even if there’s a shelter bed available? If they have a pet or if they are a smoker or if something might prohibit them from going to a shelter, how is the city supposed to weigh that and at what point would they cross a line for the court?

It’s almost a philosophical question. Like, if somebody doesn’t want to be in a shelter, are they still allowed to sleep in a public space?

Yeah. I mean, these are complicated questions that go beyond the Eighth Amendment argument but that a lot of the organizations that have reached out to the court through these friend of the court briefs are asking.

OK. I can see that the unifying element here is that in all these briefs various people from across the spectrum are saying, hello, Supreme Court. We basically need some clarity here. Give us some clarity.

The question that I have is why did the Supreme Court agree to weigh in on Grants Pass after declining to take up Boise?

Well, it’s not possible for us to say for certain because the Supreme Court does not give reasons why it has agreed to hear or to not hear a case. They get thousands of cases a year, and they take up just a few of those, and their deliberations are secret. But we can point to a few things.

One is that the makeup of the court has changed. The court has gained conservative justices in the last few years. This court has not been shy about taking up hot button issues across the spectrum of American society. In this case, the court hasn’t heard a major homelessness case like this.

But I would really point to the sheer number and the range of the people who are petitioning the court to take a look at this case. These are major players in the country who are asking the court for guidance, and the Supreme Court does weigh in on issues of national importance. And the people who are asking for help clearly believe that this is one of those issues.

So let’s start digging into the actual arguments. And maybe let’s start with the city of Grants Pass. What are the central arguments that they’re expected to make before the Supreme Court?

So the city’s arguments turn on this narrow legal issue of whether the Eighth Amendment applies or doesn’t. And they say that it doesn’t. But I actually think that in some ways, that’s not the most helpful way to understanding what Grants Pass is arguing.

What is really at the heart of their argument is that if the court upholds Grants Pass and Boise, that they are tying the hands of Grants Pass and hundreds of other towns and cities to actually act to solve and respond to homelessness. And by that, I mean to solve issues of people camping in the parks but also more broadly of public safety issues, of being able to address problems as they arise in a fluid and flexible way in the varied ways that they’re going to show up in all these different places.

And their argument is if the court accepts the Grants Pass and Boise holdings, that they will be constitutionalizing or freezing in place and limiting all of these governments from acting.

Right. This is essentially the argument being repeated again and again in those briefs that you mentioned earlier, that unless the Supreme Court overturns these decisions, it’s almost impossible for these cities to get the encampments under control.

Yes, that’s right. And they also argue they need to have flexibility in dealing actually with people who are homeless and being able to figure out using a local ordinance to try to convince someone to go to treatment, that they say they need carrots and sticks. They need to be able to use every tool that they can to be able to try to solve this problem.

And how do we make sense of that argument when Grants Pass is clearly not using that many tools to deal with homeless people? For example, it didn’t have shelters, as you mentioned.

So the city’s argument is that this just should not be an Eighth Amendment issue, that this is the wrong way to think about this case, that issues around homelessness and how a city handles it is a policy question. So things like shelter beds or the way that the city is handling their ordinances should really be left up to policymakers and city officials, not to this really broad constitutional argument. And so therefore, the city is likely to focus their argument entirely on this very narrow question.

And how does the other side counter this argument?

The homeless plaintiffs are going to argue that there’s nothing in the lower courts’ decisions that say that cities can’t enforce their laws that, they can’t stop people from littering, that they can’t stop drug use, that they can’t clear encampments if there becomes public safety problems. They’re just saying that a city cannot not provide shelter and then make it illegal for people to lay down and sleep.

So both sides are saying that a city should be able to take action when there’s public disorder as a result of these homeless encampments. But they’re pointing at each other and saying, the way you want to handle homelessness is wrong.

I think everyone in this case agrees that homelessness and the increase in homelessness is bad for everyone. It’s bad for people who are camping in the park. It is bad for the community, that nobody is saying that the current situation is tenable. Everyone is saying there need to be solutions. We need to be able to figure out what to do about homelessness and how to care for people who are homeless.

How do we wrestle with all these problems? It’s just that the way that they think about it couldn’t be further apart.

And what can you tell me about how the Supreme Court is actually expected to rule in this?

There are a number of ways that the justices could decide on this case. They could take a really narrow approach and just focus on Grants Pass and the arguments about those local ordinances. I think that’s somewhat unlikely because they’ve decided to take up this case of national importance.

A ruling in favor of the homeless plaintiffs would mean that they’ve accepted this Eighth Amendment argument, that you cannot criminalize being homeless. And a ruling for the city, every legal expert I’ve talked to has said that would mean an end to Boise and that it would break apart the current state that we’ve been living in for these last several years.

I’m struck by how much this case and our conversation has been about policing homelessness rather than actually addressing the root causes of homelessness. We’re not really talking about, say, the right to shelter or the right to treatment for people who are mentally ill and sleeping on the streets as a result, which is quite a big proportion. And at the end of the day, whatever way the ruling goes, it will be about the visibility of homelessness and not the root causes.

Yeah, I think that’s right. That’s really what’s looming in the background of this case is what impact is it going to have. Will it make things better or worse and for who? And these court cases have really become this talking point for cities and for their leaders, blaming the spike in encampments and the visibility of homelessness on these court decisions. But homelessness, everyone acknowledges, is such a complicated issue.

People have told me in interviews for the story, they’ve blamed increases in homelessness on everything from the pandemic to forest fires to skyrocketing housing costs in the West Coast, and that the role that Boise and now Grants Pass play in this has always been a little hard to pin down. And if the Supreme Court overturns those cases, then we’ll really see whether they were the obstacle that political leaders said that they were. And if these cases fall, it remains to be seen whether cities do try to find all these creative solutions with housing and services to try to help people who are homeless or whether they once again fall back on just sending people to jail.

Abbie, thank you very much.

Thank you so much.

Here’s what else you need to know today. Early on Friday, Israel attacked a military base in Central Iran. The explosion came less than a week after Iran’s attack on Israel last weekend and was part of a cycle of retaliation that has brought the shadow war between the two countries out in the open. The scale and method of Friday’s attack remained unclear, and the initial reaction in both Israel and Iran was to downplay its significance. World leaders have urged both sides to exercise restraint in order to avoid sparking a broader war in the region.

And 12 New Yorkers have been selected to decide Donald Trump’s criminal trial in Manhattan, clearing the way for opening statements to begin as early as Monday. Seven new jurors were added in short order on Thursday afternoon, hours after two others who had already been picked were abruptly excused.

Trump is accused of falsifying business records to cover up a hush money payment made to a porn star during his 2016 presidential campaign. If the jury convicts him, he faces up to four years in prison. Finally —

This is the New York Police Department.

The New York Police Department said it took at least 108 protesters into custody at Columbia University after University officials called the police to respond to a pro-Palestinian demonstration and dismantle a tent encampment.

We’re supporting Palestine. We’re supporting Palestine. 1, 2, 3, 4.

The crackdown prompted more students to vow that demonstrations would continue, expressing outrage at both the roundup of the student protesters and the plight of Palestinians in Gaza.

Free, free Palestine.

Today’s episode was produced by Olivia Natt, Stella Tan, and Eric Krupke with help from Rachelle Bonja. It was edited by Liz Baylen, fact checked by Susan Lee, contains original music by Will Reid Pat McCusker Dan Powell and Diane Wong and was engineered by Chris Wood. Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly.

That’s it for “The Daily.” I’m Katrin Bennhold. See you on Monday.

- April 19, 2024 • 30:42 The Supreme Court Takes Up Homelessness

- April 18, 2024 • 30:07 The Opening Days of Trump’s First Criminal Trial

- April 17, 2024 • 24:52 Are ‘Forever Chemicals’ a Forever Problem?

- April 16, 2024 • 29:29 A.I.’s Original Sin

- April 15, 2024 • 24:07 Iran’s Unprecedented Attack on Israel

- April 14, 2024 • 46:17 The Sunday Read: ‘What I Saw Working at The National Enquirer During Donald Trump’s Rise’

- April 12, 2024 • 34:23 How One Family Lost $900,000 in a Timeshare Scam

- April 11, 2024 • 28:39 The Staggering Success of Trump’s Trial Delay Tactics

- April 10, 2024 • 22:49 Trump’s Abortion Dilemma

- April 9, 2024 • 30:48 How Tesla Planted the Seeds for Its Own Potential Downfall

- April 8, 2024 • 30:28 The Eclipse Chaser

- April 7, 2024 The Sunday Read: ‘What Deathbed Visions Teach Us About Living’

Hosted by Katrin Bennhold

Featuring Abbie VanSickle

Produced by Olivia Natt , Stella Tan , Eric Krupke and Rachelle Bonja

Edited by Liz O. Baylen

Original music by Will Reid , Pat McCusker , Dan Powell and Diane Wong

Engineered by Chris Wood

Listen and follow The Daily Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

Debates over homeless encampments in the United States have intensified as their number has surged. To tackle the problem, some cities have enforced bans on public camping.

As the Supreme Court prepares to hear arguments about whether such actions are legal, Abbie VanSickle, who covers the court for The Times, discusses the case and its far-reaching implications.

On today’s episode

Abbie VanSickle , a Supreme Court correspondent for The New York Times.

Background reading

A ruling in the case could help determine how states, particularly those in the West, grapple with a rising homelessness crisis .

In a rare alliance, Democrats and Republicans are seeking legal power to clear homeless camps .

There are a lot of ways to listen to The Daily. Here’s how.

We aim to make transcripts available the next workday after an episode’s publication. You can find them at the top of the page.

Fact-checking by Susan Lee .

The Daily is made by Rachel Quester, Lynsea Garrison, Clare Toeniskoetter, Paige Cowett, Michael Simon Johnson, Brad Fisher, Chris Wood, Jessica Cheung, Stella Tan, Alexandra Leigh Young, Lisa Chow, Eric Krupke, Marc Georges, Luke Vander Ploeg, M.J. Davis Lin, Dan Powell, Sydney Harper, Mike Benoist, Liz O. Baylen, Asthaa Chaturvedi, Rachelle Bonja, Diana Nguyen, Marion Lozano, Corey Schreppel, Rob Szypko, Elisheba Ittoop, Mooj Zadie, Patricia Willens, Rowan Niemisto, Jody Becker, Rikki Novetsky, John Ketchum, Nina Feldman, Will Reid, Carlos Prieto, Ben Calhoun, Susan Lee, Lexie Diao, Mary Wilson, Alex Stern, Dan Farrell, Sophia Lanman, Shannon Lin, Diane Wong, Devon Taylor, Alyssa Moxley, Summer Thomad, Olivia Natt, Daniel Ramirez and Brendan Klinkenberg.

Our theme music is by Jim Brunberg and Ben Landsverk of Wonderly. Special thanks to Sam Dolnick, Paula Szuchman, Lisa Tobin, Larissa Anderson, Julia Simon, Sofia Milan, Mahima Chablani, Elizabeth Davis-Moorer, Jeffrey Miranda, Renan Borelli, Maddy Masiello, Isabella Anderson and Nina Lassam.

Katrin Bennhold is the Berlin bureau chief. A former Nieman fellow at Harvard University, she previously reported from London and Paris, covering a range of topics from the rise of populism to gender. More about Katrin Bennhold

Abbie VanSickle covers the United States Supreme Court for The Times. She is a lawyer and has an extensive background in investigative reporting. More about Abbie VanSickle

Advertisement

Welcome to our store

$6.50 flat rate shipping for orders over $65

Item added to your cart

Collection: products, i turned up t-shirt, j3.0 mind body spirit blue & yellow uni-sex t-shirt, journey butterfly black, green, and blue t-shirt - for journey graduates, journey life foundation giving, journey life water bottle, lion life black & white t-shirt, lion life hoodie - limited supply, lion life white tshirt, lioness lion life t-shirt, mr. x -gutt n' butt tshirt, rebirth black unisex t-shirt, turn up yellow tshirt, who's coming in 2nd.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.

10 Best Fantasy TV Shows That Are Based on Books

A s long as compelling narratives exist in literature, filmmakers will keep adapted them to the screen, big and small. 2024 already has an exciting lineup of book-to-movie and TV adaptations , which is another clear sign that the trend is here to stay. Between revered classics like Lisa Frankenstein , comic gems like Madame Web , and modern reads like Fool Me Once , there’s so much to look forward to for bookworms and movie buffs alike. This list, in particular, looks back at some of the best fantasy TV shows born out of books.

It’s a popular trend for filmmakers to find rich source materials with huge fan bases and turn them into fascinating TV shows. No longer confined to only readers’ imaginations, fantasy shows such as Game of Thrones , The Witcher , and The Rings of Power have become widespread fan favorites. From epic sagas to enchanting quests, these 10 shows have seamlessly brought fantasy books to life, captivating viewers with their visual splendor, imaginary worlds, and narrative depth.

Game of Thrones (2011-2019)

Game of thrones.

Release Date December 10, 2010

Cast Gwendoline Christie, Maisie Williams, Conleth Hill, Rory McCann, Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, Liam Cunningham, John Bradley, Isaac Hempstead-Wright

Main Genre Adventure

Genres Drama, Adventure, Fantasy

Celebrated as one of the greatest TV shows ever made, despite its divisive last season, Game of Thrones builds upon The Song of Ice and Fire book series crafted by George R.R. Martin. Published in 1996, Game of Thrones ’ source material received the 1997 Locus Award, among many others, for its exceptional quality, cultivating a dedicated fan base eager to see its 2011 HBO adaptation. Upon arrival on TV, it captivated not only long-time fans of the books, but also lovers of well-written shows.

Westeros' Wondrous World

Just as awesome as the book, and packed with complex characters and fantastical elements, Game of Thrones faithfully adheres to its source material, especially since the author was part of the production. Backed by a large budget, creators David Benioff and Dan Weiss — and, of course, the impeccable cast and crew — captured not only the book’s wondrous world, but brought the complex characters to vivid life. Stream on Max

The Wheel of Time (2021-Present)

The wheel of time.

Release Date 2021-00-00

Cast Daniel Henney, Barney Harris, Sophie Okonedo, Rosamund Pike, Peter Franzen, Michael McElhatton

Main Genre Fantasy

Genres Sci-Fi, Fantasy

Comprising 14 volumes, The Wheel of Time is a high-fantasy book series featuring magic, prophecies, and a richly developed world with diverse cultures and societies, where the fight between good and evil unfolds. The first season of the TV series premiered on Prime Video in November 2021, bringing to life Robert Jordan’s words (his literary series was later completed by Brandon Sanderson).

A Satisfying and Incredible Adaptation

The team behind Prime Video's adaptation of The Wheel of Time invested time in translating the heart and soul of Jordan’s fantasy books into a very satisfying experience, ensuring a balance between familiarity to readers and openness to newcomers. Though there are some changes to certain characters’ backstories, they do not detract from the overarching plot. Rosamund Pike shines in every scene as Moiraine Damodred, and the cast of young actors delivers commendable performances. We expect the upcoming third season will maintain the show’s brilliance thus far. Stream on Prime Video

His Dark Materials (2019-2022)

His dark materials.

Release Date 2019-00-00

Cast Ruta Gedmintas, Will Keen, Ruth Wilson

Produced by the BBC and HBO, His Dark Materials is an amazing fantasy show derived from Paul Pullman’s best-selling young adult series of the same name. Set in a multiverse, the narrative follows the adventures of a young girl named Lyra Belacqua. Throughout its four-season run, the series received acclaim for its elaborate world-building, well-drawn characters, and treatment of profound themes.

An Expansive High-Fantasy Series

Praised for being an accurate representation of its source material — and superior to the 2007 movie adaptation of The Golden Compass — this series is anything but predictable. Unlike The Golden Compass, His Dark Materials embraces darkness and fearlessly addresses difficult issues of morality, prophecy, mythology, death, and duty. It also goes deeper into character relationships and their backgrounds. With its impressive set, incredible cast, excellent music, well-written plot and intricate world-building, it is quite clear its high budget was effectively utilized. Stream on Max

Related: 10 Underrated Fantasy TV Series That Deserve More Love

The Sandman (2022-Present)

The sandman.

Release Date August 5, 2022

Creator Neil Gaiman, David S. Goyer, Allan Heinberg

Cast Gwendoline Christie, Patton Oswalt, Tom Sturridge, Boyd Holbrook, David Thewlis, Charles Dance

Read Our Season 1 Review

Over the past 30 years, since Neil Gaiman’s Sandman comic book series was launched between 1989 and 1996, several attempts to adapt it to the big screen have failed. But in 2022, Netflix stepped in and transformed this beloved comic book into a more cohesive 10-part series that chronicles the story of Dream.

Spellbinding and Intriguing

With Gaiman serving as part of the production team, The Sandman certainly feels like being immersed in the spellbinding world of the eponymous graphic novels. Having the original creator in the project helped to ensure a faithful adaptation. Additionally, from Paul Sturridge to the rest of the ensemble, each actor perfectly embodies the essence of the characters’ personalities. Fans of both books and shows will be delighted to know that a second season is in development . Stream on Netflix

Good Omens (2019-Present)

Cast David Tennant, Michael Sheen, Michael McKean, Frances McDormand

Main Genre Comedy

Derived from the 1990 fantasy novel of the same name, written by Gaiman and Terry Pratchett, Good Omens sees Gaiman as the showrunner. It tells the unique story of the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley, who join forces to prevent the end of the world.

A Clever, Unique, and Faithful Adaptation

With numerous positive reviews heaped on this show, it is quite obvious Good Omens is indeed a standout in the fantasy genre. The concept of angels and demons teaming up to prevent an apocalypse presents a unique and intriguing narrative. The sharp dialogue that perfectly captures the humor in the source material also contributes to its well-deserved acclaim.

Ultimately, what makes Good Omens great is its blend of sharp humor, strong characterization, and unique storytelling, resulting in a faithful adaptation that resonates with both devoted fans of the source material and new audiences. Stream on Prime Video

Shadowhunters (2016-2019)

Shadowhunters.

Release Date August 1, 2016

Cast Isaiah Mustafa, Katherine McNamara

Main Genre Sci-Fi

Shadowhunters marks the first TV series adaptation of Cassandra Clare’s urban fantasy novel series, but it isn’t the first book-to-screen adaptation. Cassandra’s The Mortal Instruments was first made into a feature film that starred Lily Collins as Clary Flay. Like the movie, the show followed the story of Clary Flay, a human-angel who discovers she is a Shadowhunter.

A Fresh Journey Worth Exploring

Shadowhunters isn’t entirely a faithful adaptation, as it takes liberties by expanding the source materials and diverging from the original plot, providing its own take on the world created by author Clare. Notwithstanding this difference, the show is highly intriguing and will have many hooked from the very beginning to the end. With its special effects, acting, and writing improving with each season, this proves to be a new Shadow World worth exploring. Stream on Hulu

The Shannara Chronicles (2016-2017)

The shannara chronicles.

Release Date January 5, 2016

Cast Austin Robert Butler, Malese Jow, Manu Bennett, Ivana Baquero

The Shannara Chronicles is based on the novel trilogy by Terry Brooks. Primarily based on the second book in the original Shanara book series, this TV show unfolds in a post-apocalyptic future threatened by the return of demons. The heroes, Wil, Eretria, and Amberle, must join forces to prevent this.

An Overall Fun Fantasy Show

Though not reaching the epic heights of Game of Thrones , both the show and books offer enjoyable entertainment. The plot may veer into the absurd at times, but viewers will be drawn to the endearing characters. Fans of the books who embrace the divergences between the book and the show will certainly discover a fresh perspective on the Shannara World, while new audiences will find it a fascinating entry into this fantastical realm. Stream on Tubi

The Witcher (2019-Present)

The witcher.

Release Date December 20, 2019

Cast Eamon Farren, Mimi Ndiweni, Anya Chalotra, Freya Allan, Liam Hemsworth, Henry Cavill

Main Genre Drama

Read Our Review of Season 3, Volume 1

Created by Lauren Schmidt Hissrich, The Witcher , adapted from Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski's eponymous books, primarily revolves around the monster hunter, Geralt of Rivia (Henry Cavil). Celebrated for its masterful storytelling, visually stunning fight scenes, and perfectly developed characters, The Witcher is a fan-favorite Netflix adaptation.

A Fantasy Wonderland

A treat for fantasy enthusiasts, The Witcher unveils a world teeming with sorcery, demons, various kinds of creatures, and a well-crafted world of complex political intrigue. With all of these elements, the Continent certainly feels alive and expansive, like a fantasy wonderland, which contributes to the overall immersive experience. Despite some differences from the book source, the show certainly captures the essence of Sapkowski’s fantasy universe. The Witcher may take some time to accclimate to, but as the series evolves into a captivating journey, it becomes quite addictive . Stream on Netflix

The Magicians (2015-2020)

The magicians.

Release Date 2016-01-00

Cast Summer Bishil, Stella Maeve, Hale Appleman, Arjun Gupta

Genres Drama, Horror, Fantasy

If you love magical books or TV shows, or by chance believe in the existence of magic, then The Magicians is tailor-made for you. Adapted from Lev Grossman’s beloved Magicians trilogy, this show brings to life a delightful realm with endearing characters, rivaling its source material. Premiering on Syfy in 2015, it follows Quentin Coldwater, a high school student who discovers that the magical world he reads about in books actually exists.

Immersive and Exceptional

Drawing inspiration from other great fantasy movies like Harry Potter and Chronicles of Narnia , The Magicians immediately caters to those who cherish these classics. Rather than just focusing on a single character like the book does, however, the show unfolds from the perspectives of other core characters, like Alice, Penny, Margo, Elliot, and others. This multifaceted approach elevates the show to a more profound and exceptional binge-worthy fantasy. Stream on Netflix

Shadow and Bone (2021-2023)

Shadow and bone.

Cast Ben Barnes

Genres Sci-Fi

Shadow and Bone is a fantasy TV series that blew minds when it premiered on Netflix in April 2021. It is based on the Grishaverse novels by author Leigh Bardugo, specifically the Shadow and Bone trilogy, which includes the books: Shadows and Bone , Siege and Storm, and Ruin and Raising . Set in the war-torn world of Ravka, it follows Alina, who discovers the key to reuniting her country.

Compelling Mix of Magic, Romance, and Adventure

Shadow and Bone has generally been well-received by both fans of the Grishaverse novels and the newcomers to this world created by Bardugo. It received positive reviews for its compelling mix of magic, romance, adventure, and political intrigue. Other great aspects include: phenomenal character development, a diverse cast, an engaging storyline, and a visually stunning world. However, being loved didn’t save it from getting canceled after just two seasons on Netflix. That being said, its cancellation had nothing to do with its quality, as it is a fantastic adaptation of Bardugo's novels. Stream on Netflix

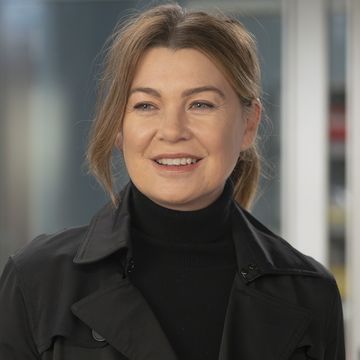

'When Calls the Heart' Star Erin Krakow on Elizabeth's "Self-Discovery" in Season 11

In an exclusive interview, the Hallmark actress reveals what's next for her character.

This story contains light spoilers for When Calls the Heart season 10.

The actress is famous for portraying Elizabeth Thatcher Thornton, and her character has embraced many trials and tribulations throughout her tenure on the drama. The schoolteacher has dealt with the loss of her husband Jack ( Daniel Lissing ), the birth of her son, finding love again with Lucas Bouchard ( Chris McNally ) and eventually ending the couple's engagement at the end of season 10.

For Erin, what made When Calls the Heart season 11 so important was the fact Elizabeth is not just looking out for those she cares about most. Elizabeth is on a journey to discover who she is amid the start of something new.

"Season 10 was a very challenging emotional time for Elizabeth," Erin tells Good Housekeeping over Zoom. "A lot of self-reflection, a lot of trying to figure out what's the right move and is she with the right person. Moving into season 11, it was important for me to explore the sides of Elizabeth that show her celebrating life a bit more and being open to those. There's a real lightness and joy that comes with that."

Indeed, Elizabeth takes focus on figuring out her own identity in When Calls the Heart season 11 , starting with asking Rosemary Coulter to help cut her hair in the premiere episode. But while switching up her looks is one element on her road to self-discovery, there's one other thing that fans have waited years to see happen.

As Erin explains, season 11 is unique for Elizabeth as she can finally acknowledge her feelings for Mountie Nathan Grant ( Kevin McGarry ), with whom she's had an on-and-off friendship since he first appeared in season 6. While Nathan has expressed his desire to be in a relationship with her, viewers know she eventually chose Lucas as her next beau, before she chose to end their relationship amid her own hesitation to choose between him and Nathan.

Now that she's finally single, Erin says Elizabeth is ready to take her relationship with Nathan to the next level. But unlike her previous romances, Erin says the twosome's road to love is much softer for a specific reason.

"When I think about the way [ When Calls the Heart is] handling it, it's grown up," she says. "For Nathan and Elizabeth, they're busy people. She's trying to raise her kid, she's a teacher. He's trying to raise his kid [Allie, played by Jaeda Lily Miller ], he's a Mountie. They've got lives and responsibilities. That's not necessarily a sexy way of approaching it, but that's life for them. It's a mature kind of love that ends up being very passionate, if I may say. Sometimes it's just nice to see a couple of grown people fall in love."

So, what else is Erin excited for fans to see in When Calls the Heart season 11 ? As the actress emphasizes, Elizabeth is expanding her horizons, but she's not the only one.

"There have been so many changes in the rollercoaster of Elizabeth's journey," Erin says. "Season 11 is no exception. We're breathing new life into Elizabeth and into the fabric of the town in various ways. And Nathan is there and there's all this excitement and change happening in Hope Valley. And so not only for Elizabeth, but for everyone in town, it feels like a new beginning."

When Calls the Heart season 11 airs Sundays at 9 p.m. ET on Hallmark .

@media(max-width: 64rem){.css-o9j0dn:before{margin-bottom:0.5rem;margin-right:0.625rem;color:#ffffff;width:1.25rem;bottom:-0.2rem;height:1.25rem;content:'_';display:inline-block;position:relative;line-height:1;background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-o9j0dn:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/goodhousekeeping/static/images/Clover.5c7a1a0.svg);}}@media(min-width: 48rem){.loaded .css-o9j0dn:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/goodhousekeeping/static/images/Clover.5c7a1a0.svg);}} Must-See TV Shows

'Criminal Minds' Cast Makes TikTok Reveal

'Wheel of Fortune' Shares First Ryan Seacrest Clip

All Your 'Grey's Anatomy' Season 21 Qs, Answered

'9-1-1' Fans Are "Shook" Over Oliver Stark TikTok

'Suits' Stars Excite Fans With Reunion News

Where Is ‘The Kelly Clarkson Show’ Filmed?

See Wilmer Valderrama's Emotional 'NCIS' Note

A Guide on How to Vote for 'American Idol' in 2024

'S.W.A.T.' Star Reveals Shocking Season 8 News

When Is Pat Sajak's Final 'WoF' Episode?

Why 'Station 19' Fans Fear This Character Will Die

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Journey Life TV is founded by Dr. Joseph L. Williams, a pastor, speaker, author, and life coach. It offers a spiritual process of transformation that integrates mind, body, and spirit through books, programs, and events.

Journey Life TV is a channel that provides content designed to uplift and edify any person who desires holistic growth or transformation. This is a place whereby knowledge and discussion related ...

Joseph L Williams is a public figure who teaches and explains the Word of God on his Facebook page journeylife.tv. He has 31K followers and 30K likes on his page, where he posts photos and videos of his ministry.

Follow Journey Life TV on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/journeylifetv-----Journey Life TV provides content designed to uplift ...

REGISTER FOR The 40-Day Turn Up Process Before Registration Ends. Weekly Video Training From Dr. Joe. A Private Member-Only Video Portal. Access to our Private 40-Day Turn Up Community Group. An Accountability 40-Day Turn Up Team Leader Access to Recipes, Worksheets, Templates, and Resources

Join Our Free Trial. Get started today before this once in a lifetime opportunity expires.

www.journeylifetv.com

The next session of the 40 Day Turn Up is here! If you DON'T know what it is and want to know about it, simply go to this link and watch the video! If you want to change your life and become the VERY...

8,842 Followers, 2 Following, 539 Posts - See Instagram photos and videos from Dr Joe (@journeylifetv)

Ep. 007 - "5 Things you DON'T need to lose weight or remain healthy" This is the seventh episode of "Journey Life" podcast. In this episode, Dr. Joseph L. Williams discusses: 5 Things you don't need to lose weight or remain healthy. This episode uncovers what you may see often on TV, in magazines or myths circulated by friends.

Sign in to the member portal to join Dr. Joe for a 40-day Journey to lose weight and improve your health. The Journey Life is a TV show that features real people and their transformations.

The Journey is a spiritual process that takes you deep within yourself and helps you transform your mind, body, and spirit. The web page offers a 40-day Journey for weight loss, but registration is no longer available.

Live Coaching Session--If you desire to join a future session of the 40 Day Turn Up, visit us at www.journeylife.tv

Share your videos with friends, family, and the world

Shop Journey Life TV. Home; 40DTU Collection; Journey Collection; Giving; ... Lion Life Hoodie - LIMITED SUPPLY Regular price From $45.00 USD Regular price $0.00 USD Sale price From $45.00 USD Unit price / per . Lioness Lion Life T-shirt Lioness Lion Life T-shirt ...

The Journey devotional is a Devotional specifically written for those who are matriculating through any process with "40 Days with Dr Joe." The journal provides daily (40 Days) scriptures, lessons, points of reflection, daily challenges as well as a place for each participants daily journal entry. The design is to help each participant ...

Charles's journey on My 600-lb Life was an interesting one. He and Dr. Now butted heads several times and Charles often didn't follow Dr. Now's directions. Usually, when this happens on the show, the individual ends up gaining weight and getting farther away from their goal.

Yadi Rodriguez, cleveland.com. " My 600-lb. Life " Season 12 continues tonight, Wednesday, April 17, at 8 p.m. Eastern on TLC, with the season's sixth episode. If you've cut the cord but ...

From the Heisman to white Bronco chase and murder trial: A timeline of O.J. Simpson's life. Once the most high-profile celebrity in the country, O.J. Simpson died Wednesday at the age of 76. The ...

April 19, 2024. Share full article. Hosted by Katrin Bennhold. Featuring Abbie VanSickle. Produced by Olivia Natt , Stella Tan , Eric Krupke and Rachelle Bonja. Edited by Liz O. Baylen. Original ...

Regular priceSale priceFrom $10.00 USD. Unit price/ per. Journey Life Water Bottle. Sale. Journey Life Water Bottle. Regular price$4.00 USD. Regular price$6.50 USD Sale price$4.00 USD. Unit price/ per.

After this serial, Divyanka Tripathi became the highest-paid actress in India. When the serial was on air, Divyanka charged Rs. 1 lakh to Rs 1.5 lakh per episode. The show changed Divyanka's life, and her net worth spiked to Rs. 40 crore. Divyanka is now hailed as one of the richest and most successful actresses in television.

Shadow and Bone. CastBen Barnes. Main Genre Sci-Fi. Genres Sci-Fi. Seasons0. Shadow and Bone Grishaverse Shadow and Bone Shadows and Bone Siege and Storm, Ruin and Raising. Shadow and Bone ...

As the actress emphasizes, Elizabeth is expanding her horizons, but she's not the only one. "There have been so many changes in the rollercoaster of Elizabeth's journey," Erin says. "Season 11 is ...