- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Birth of the Tour de France

By: Christopher Klein

Updated: May 8, 2023 | Original: June 28, 2013

On July 1, 1903, 60 men mounted their bicycles outside the Café au Reveil Matin in the Parisian suburb of Montgeron. The five-dozen riders were mostly French, with just a sprinkle of Belgians, Swiss, Germans and Italians. A third were professionals sponsored by bicycle manufacturers, the others were simply devotees of the sport. All 60 wheelmen, however, were united by the challenge of embarking on an unprecedented test of endurance—not to mention the 20,000 francs in prize money—in the inaugural Tour de France.

At 3:16 p.m., the cyclists turned the pedals of their bicycles and raced into the unknown.

Nothing like the Tour de France had ever been attempted before. Journalist Geo Lefevre had dreamt up the fanciful race as a stunt to boost the circulation of his struggling daily sports newspaper, L’Auto. Henri Desgrange, the director-editor of L’Auto and a former champion cyclist himself, loved the idea of turning France into one giant velodrome. They developed a 1,500-mile clockwise loop of the country running from Paris to Lyon, Marseille, Toulouse, Bordeaux and Nantes before returning to the French capital. There were no Alpine climbs and only six stages—as opposed to the 21 stages in the 2013 Tour— but the distances covered in each of them were monstrous, an average of 250 miles. (No single stage in the 2013 Tour tops 150 miles.) Between one and three rest days were scheduled between stages for recovery.

The first stage of the epic race was particularly dastardly. The route from Paris to Lyon stretched nearly 300 miles. No doubt several of the riders who wheeled away from Paris worried not about winning the race—but surviving it.

Unlike today’s riders, the cyclists in 1903 rode over unpaved roads without helmets. They rode as individuals, not team members. Riders could receive no help. They could not glide in the slipstream of fellow riders or vehicles of any kind. They rode without support cars. Cyclists were responsible for making their own repairs. They even rode with spare tires and tubes wrapped around their torsos in case they developed flats.

And unlike modern-day riders, the cyclists in the 1903 Tour de France, forced to cover enormous swathes of land, spent much of the race riding through the night with moonlight the only guide and stars the only spectators. During the early morning hours of the first stage, race officials came across many competitors “riding like sleepwalkers.”

Hour after hour through the night, riders abandoned the race. One of the favorites, Hippolyte Aucouturier, quit after developing stomach cramps, perhaps from the swigs of red wine he took as an early 1900s version of a performance enhancer.

Twenty-three riders abandoned the first stage of the race, but the one man who barreled through the night faster than anyone else was another pre-race favorite, 32-year-old professional Maurice Garin. The mustachioed French national worked as a chimney sweep as a teenager before becoming one of France’s leading cyclists. Caked in mud, the diminutive Garin crossed the finish line in Lyon a little more than 17 hours after the start outside Paris. In spite of the race’s length, he won by only one minute.

“The Little Chimney Sweep” built his lead as the race progressed. By the fifth stage, Garin had a two-hour advantage. When his nearest competitor suffered two flat tires and fell asleep while resting on the side of the road, Garin captured the stage and the Tour was all but won.

The sixth and final stage, the race’s longest, began in Nantes at 9 p.m. on July 18, so that spectators could watch the riders arrive in Paris late the following afternoon. Garin strapped on a green armband to signify his position as race leader. (The famed yellow jersey worn by the race leader was not introduced until 1919.) A crowd of 20,000 in the Parc des Princes velodrome cheered as Garin won the stage and the first Tour de France. He bested butcher trainee Lucien Pothier by nearly three hours in what remains the greatest winning margin in the Tour’s history. Garin had spent more than 95 hours in the saddle and averaged 15 miles per hour. In all, 21 of the 60 riders completed the Tour, with the last-place rider more than 64 hours behind Garin.

For Desgrange, the race was an unqualified success. Newspaper circulation soared six-fold during the race. However, a chronic problem that would perpetually plague the Tour de France was already present in the inaugural race—cheating. The rule-breaking started in the very first stage when Jean Fischer illegally used a car to pace him. Another rider was disqualified in a subsequent stage for riding in a car’s slipstream.

That paled in comparison, however, to the nefarious activity the following year in the 1904 Tour de France. As Garin and a fellow rider pedaled through St. Etienne, fans of hometown rider Antoine Faure formed a human blockade and beat the men until Lefevre arrived and fired a pistol to break up the melee. Later in the race, fans protesting the disqualification of a local rider placed tacks and broken glass on the course. The riders acted a little better. They hitched rides in cars during the dark and illegally took help from outsiders. Garin himself was accused of illegally obtaining food during a portion of one stage. The race was so plagued by scandal that four months later Desgrange disqualified Garin and the three other top finishers. It, of course, wouldn’t be the last time a Tour winner was stripped of his title.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Performance

- Strava Updates

- Tour de France

- English (US)

- Español de América

- Português do Brasil

Get Started

Everything You Need to Know About the Tour de France

, by Max Leonard

In just a few short weeks, the men’s pro peloton will take to the roads of France (and Italy too, this year) for the 111th edition of the Tour de France . If you’re new to the sport, that’s a lot to catch up on – so here’s our beginner’s guide to the history and the present of the world’s greatest cycle race.

The origins of the tour de france.

The first Tour de France took place in 1903, dreamed up as a publicity stunt for an ailing sports newspaper, L’Auto , by its editor, Henri Desgrange, and his assistant Géo Lefèvre. At that time, six-day racing in the velodrome was incredibly popular, and road races tended to be very long: Bordeaux–Paris was around 560km / 348 mi and Paris–Brest–Paris a whole lot longer at around 1200km / 745 mi. The new Tour de France was six stages in total, held concurrently over 15 days and the longest stage, from Nantes to Paris was 471km / 293 mi.

JOIN The official Tour de France Club on Strava

Beforehand, nobody was sure that the idea of multi-stage road racing would take off, but it was an instant success with the French public. The race started and ended in Paris, and the overall title was won by pre-race favourite Maurice Garin. Garin also won the 1904 edition, which was contested over the same course, but was subsequently disqualified and stripped of his win – the rumour is that Garin and several other top riders cheated and took a train!

For many years, the race ended at the Parc des Princes velodrome in the north of Paris, but in 1975 a finish on the Champs-Élysées was introduced, and that has become traditional.

The Mountains of the Tour de France

While the very early races took on some formidable climbs by any standards, the real high mountains did not make an appearance until 1910. That year, the race organizers optimistically included some Pyreneen passes on the route, including the now-classic Tourmalet , now measured as a 17.1 km / 10.63 mi climb at an average of 7.3%, on what was then not much more than a logging track. Based on the success of that, the Col du Galibier – a moody and menacing 2,645m / 8678 ft tall pass was added in 1911. The famous rocky summit of Mont Ventoux in Provence was introduced in 1951, and Alpe d’Huez , now the scene of the largest fan party, in 1952.

RELATED: Tour de France 2024 Route Preview: It’s Climby!

Over the years, gradually, climbing – rather than just out-and-out endurance – became more important to the race. The first Pyreneen stage in 1910 was 326km / 204 mi long and included five mountain passes . Even in the 1980s, mountain stages might have been 200 kilometers / 125 mi or more; these days, a mountain stage is more likely to be 160km / 100 mi, and designed to provoke explosive, exciting racing. However, post-war, the format has remained relatively stable: 21 days racing around France, ending in Paris but often starting elsewhere (even in a neighboring country); with the majority of France being covered, and always a visit to the Pyrenees and the Alps. A Tour without one of the classic climbs is unheard of, and if, say, Mont Ventoux, doesn’t get included for a long run of years, then there will be a popular outcry.

In 2024, because of the Olympic Games in Paris, the Tour is finishing outside the capital for the first time – in Nice in south-eastern France.

The Tour de France Teams

In the earliest Tours, riders were competing solo and any help between them was prohibited. However, even in the 1900s, bicycle manufacturers sponsored the best riders, and it didn’t take long before loose alliances between them began to be forged – much to the organizer’s chagrin. To Desgrange, this collaboration didn’t seem like a pure or ‘fair’ test of strength.

RELATED: Tour de France Femmes 2024 Route Preview: Heading up the Alpe d’Huez!

To try to combat the power of the manufacturers, for much of the twentieth century the race was run with national teams, and France even had several regional outfits. But in 1962 the race returned definitively to the trade-team format we know today, with large commercial sponsors (or even now national entities) giving teams their money and identity. For the past few years, there have been 22 teams at the Tour with eight riders each, and, according to its talents, each team’s objectives may be very different.

The race for the Yellow Jersey

The biggest prize at the Tour has always been the General Classification (GC) – rewarding the rider who records the lowest cumulative time in all the stages over the whole Tour. Since 1919, the GC leader has been denoted by the yellow jersey (maillot jaune) they wear each day, and the ultimate objective is to be wearing the yellow jersey on the final podium in Paris. Small time bonuses on the GC are often awarded mid-race, either at the top of climbs or at intermediate sprint points.

RELATED: Your Year With The Pros: A Guide to the 2024 Road Racing Season

Jacques Anquetil, Eddy Merckx, Bernard Hinault, and Miguel Indurain have won the most Tours, with five each. In 1999, Lance Armstrong began a record-breaking run of seven consecutive Tour wins but was stripped of his titles in 2012 for doping offenses.

However, aside from the GC, each day’s stage is a separate race in its own right, and a stage win at the Tour can be the pinnacle of a rider’s career. How any given stage plays out depends on the terrain. Usually, the whole bunch will set off together as one big ‘peloton’, while a few riders try to work together to establish a breakaway group that will try to build up a big enough lead to contest the stage win. On flat stages, the peloton will generally catch the breakaway and the finish will be a bunch sprint. Rolling stages are the territory of the powerful riders known as puncheurs , while days with multiple smaller obstacles may favor a breakaway specialist.

Each day, every team will head out with a plan and try to execute it, with riders working together to achieve the goal: helping their GC target finish strongly, for example, setting up their climber for the final climb, or leading out their sprinter in the closing kilometers. Riders who sacrifice their personal ambitions or standing for the team goal are known as domestiques . Their job can be absolutely vital, and yet without the glory of the star riders their strength, dedication, and tactical awareness can sometimes go unrecognized.

That may sound a little formulaic, but the best thing about bike racing is its unpredictability. There’s an alchemy in how the efforts of 196 racers with differing objectives combine with the unexpected challenges of the road, and a sprinkling of human strength and weakness, to make something exciting and unexpected happen.

RELATED: Gran Fondo Focus: Bucket List Events

The Polka-Dot, Green, and White Jerseys at the Tour de France

In addition to the GC, there are three other important in-race competitions. The mountain classification is given to the rider who gains the most points for reaching mountain summits first. It first came into being in the 1930s but is now characterized by the distinctive polka-dot jersey, which dates from the 1970s when the classification was sponsored by a chocolate brand. All of the significant climbs in each Tour are categorized, with 4 being the smallest and HC ( hors catégorie or ‘beyond categorization’) the largest. The bigger the summit, the more points awarded to the first man over, with a descending amount given to a select number after him. With the tendency towards summit finishes – which attract a premium number of points – in recent years the yellow jersey has often also won the polka-dot jersey.

The green jersey, meanwhile, is often known as the sprinters’ jersey, but is properly speaking the points jersey. It goes to the rider who accrues the most points, at stage finishes on flatter days and at intermediate sprint points – of which there is always at least one every day. Again, like the mountains jersey, a set number is awarded to the first man, and lesser amounts to the riders after him. Though it is often won by a ‘pure’ sprinter, the most successful rider in the history of the green jersey is Peter Sagan, a recently retired superstar Slovakian whose skill and consistency across the whole Tour (including the hillier stages) made up for what he lacked in top-end speed for the really flat days.

RELATED: Cyclists You Should Follow on Strava

Finally, the white jersey is awarded to the best young rider, under 25 years old when that year’s Tour starts. However, given the trend of younger and younger riders winning the Tour, the yellow jersey and the white jersey can often be the same guy.

The Spectators at the Tour de France

In terms of the number of live attendees, the Tour de France is the biggest sporting event in the world. Because it takes place on public roads, unless you have a VIP hospitality package right at the finish line, it is free to watch. If the Tour is passing through a village, the whole population will take to the streets for barbecues, wine, and music. Mountain stages, too, can be very rewarding for spectators, with huge crowds – into the hundreds of thousands – lining the road for an all-day (and sometimes all-night) party, waiting for the helicopters to start flying overhead, the team cars to whizz past and finally the riders to slowly ascend – all surrounded by dramatic scenery. If you ever get the chance, it’s highly recommended.

RELATED: A True Classic: The History of Paris-Brest-Paris

However, watching on TV is in some ways better! With the complexity of the different competitions, the multiple races-within-a-race, and the different story arcs ranging from the single day’s result to the whole three-week affair, the amount of tension and intrigue in a good Tour de France can be mind-blowing.

Yes, on slow days, you might get to know far more about chateaux, vineyards, and local cheeses than you thought you needed to, but even that can be fun. The Tour has often been described as one big advert for the French tourist board, and watching the countryside change over the course of the race – plus those amazing helicopter shots of riders in the mountains – is a real feast.

So put a date in your diary, and here’s to hoping for a vintage Tour de France 2024.

Related Tags

More stories.

Perfecting the Art of Race-Day Peaking

Multi-Sport

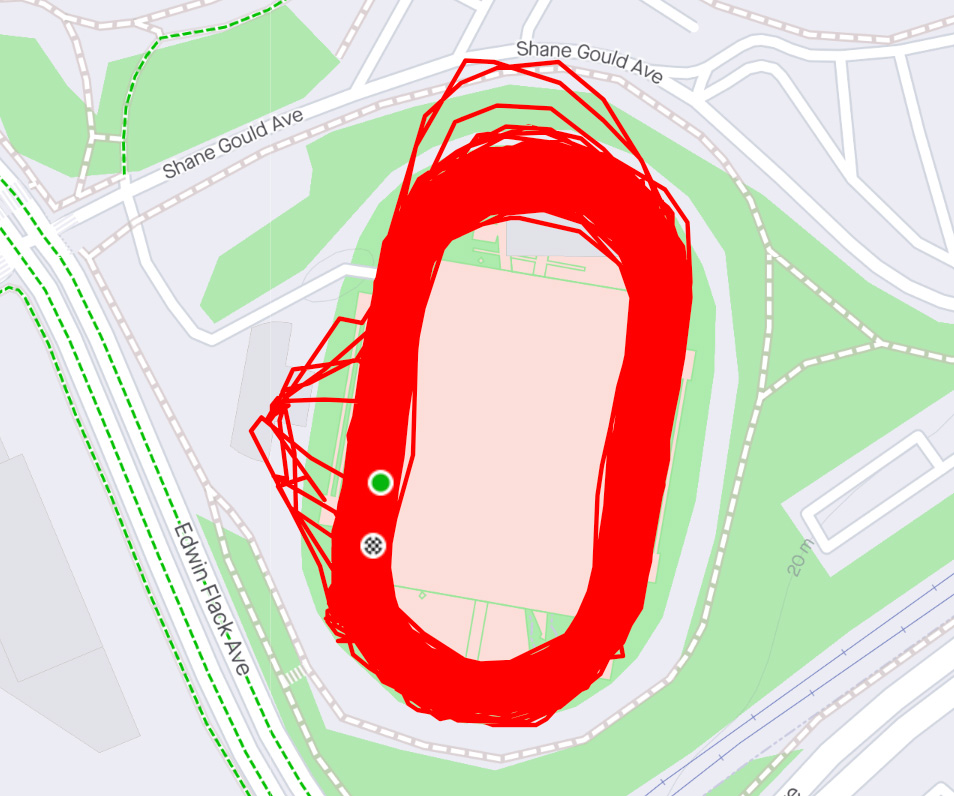

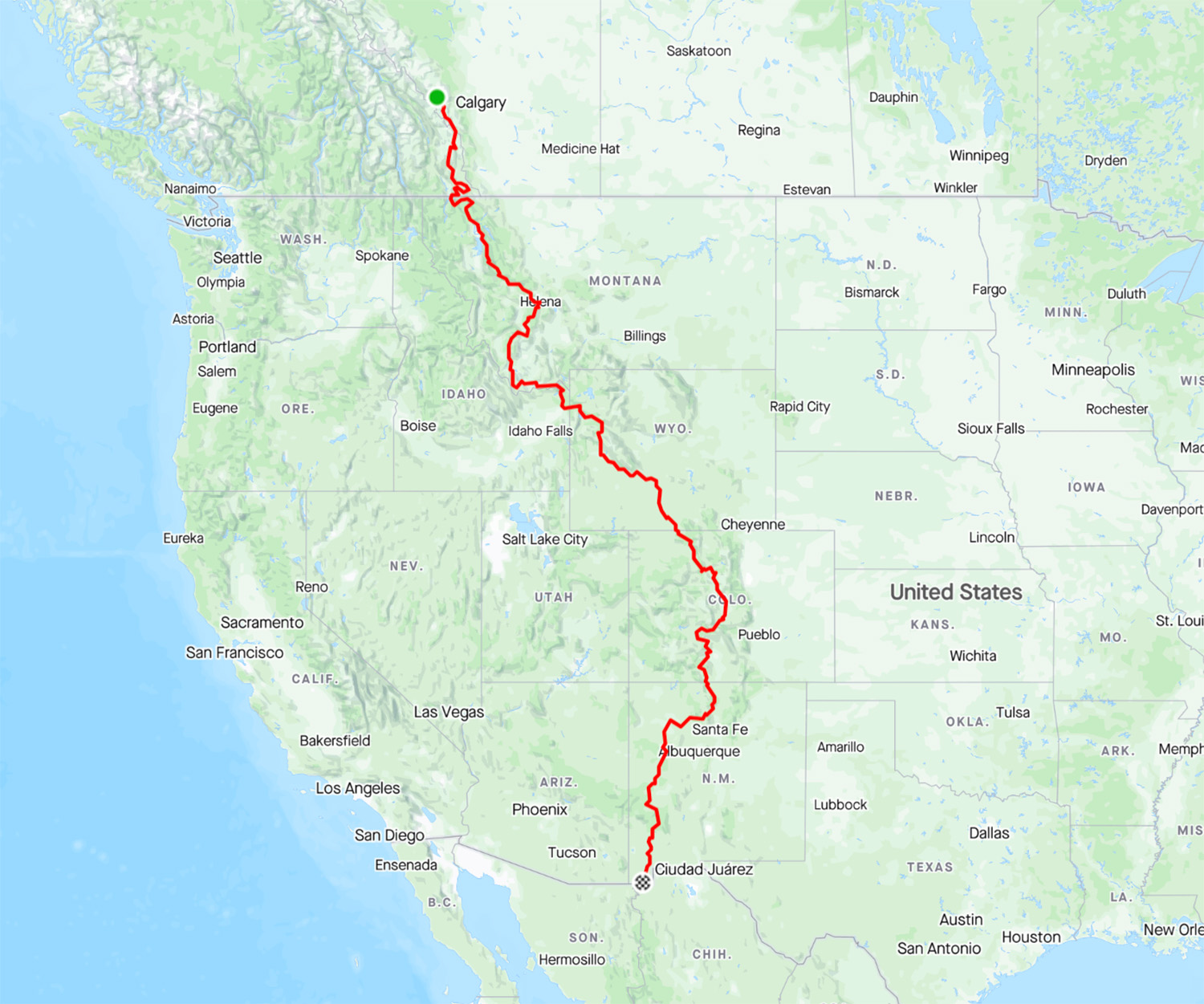

Spotted on Strava: Two Tours, an Epic Track Session & Minecraft

Spotted on Strava: Two Epic Tours, Western States 100 & Glastonbury

A Brief History Of: The Tour de France

T he Tour de France, which kicks off July 5, is a grueling test of human endurance, a three-week 2,175mile (3,500 km) race stretched over 21 stages, nine of them in the mountains. But in some ways the modern Tour is easier than races past. In the early 20th century, competitors pedaled the dirt roads of France through the night on fixed-gear bikes, evading human blockades, route-jamming cars and nails placed on the road by fans of other riders. Between stages, teams feasted on banquets and champagne; before climbs, they fortified with cigarettes.

The race was the brainchild of Henri Desgrange, a Parisian magazine editor who launched it in 1903 with 60 riders in a bid to boost circulation. It worked: Tour coverage helped Desgrange’s magazine boom, and the race soon became more popular than he could have dreamed. With fans lining the roads to see riders up close, by the 1920s the Tour included more than 100 cyclists from throughout Europe. But as the competition grew fiercer and the race more commercialized, champagne and nicotine gave way to more effective–and insidious–performance boosters. In 1967, British rider Tom Simpson died midrace after taking amphetamines, prompting the event to adopt drug-testing. In 1998 authorities disqualified the Festina team after finding the red blood cell–boosting drug EPO in their car. The winner of the 1996 race, Bjarne Riis, admitted in 2007 that he had used EPO, just months before Floyd Landis became the first Tour winner stripped of his title on charges of using synthetic testosterone in 2006. The Tour now tests athletes rigorously–stage winners are screened daily–although the victor in this year’s race will still be allowed a sip of champagne.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- ‘We’re Living in a Nightmare:’ Inside the Health Crisis of a Texas Bitcoin Town

- Why Are COVID-19 Cases Spiking Again ?

- Lionel Messi Isn't Finished Yet

- Fiji’s Fiery Battle Against Plastics

- Column: AI-Driven Behavior Change Could Transform Health Care

- How to Watch Lost in 2024 Without Setting Yourself Up for Disappointment

- How Often Do You Really Need to Wash Your Sheets ?

- The 15 Best Movies to Watch on a Plane

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at [email protected]

- L'Etape Australia

- Santos Festival of Cycling

- Spring Classics

- Giro d'Italia

- Tour de France

- La Vuelta Espana

- View All Tours

- Pro Tour Hosts

- Company News

- Mummu Memories

- Where We Visit

The prestigious Tour de France is perhaps the most well-known annual multiple stage bicycle race in the world today. This 21 stage Grand Tour is held primarily in France, with passes through neighbouring countries occurring regularly.

The respect of the Tour de France is largely tied to its rich history, one that stretches back over a century. The first race, organised in 1903, was originally developed to increase sales for the newspaper L'Auto – not quite the pedigree many would have imagined!

The first Tour de France

The editor for L’Auto, Henri D Desgrange, was the person responsible for the development of the tour itself. With the Tour De France, Desgrange invented bicycle stage racing. The first Tour, far from an unbridled success, attracted only 15 entrants due to the initially high entry fee. This was amended by offering a daily allowance to riders, in addition to a 12,000 franc first prize. The prize money, a huge amount at the time, enticed 60-80 entrants to enter, only 24 remained of which remained at the beginning of the fourth stage.

After the Tour concluded, L’Auto had more than doubled its circulation in France – the exact purpose for the development of the Tour de France.

The development of the Tour de France

The original 1903 incarnation of the Tour de France assured organisers that they were onto something big. The next few years saw the format change frequently, with issues such as cheating, fighting, scoring methods, and route development making sure the Tour had many iterations during its early years. Even with these changes, the Tour de France has been held in July without fail since its first year, with the only exceptions being through the two World Wars.

Strict rules regarding bicycles were also enforced by Desgrange, such as cyclists having to repair their own bicycles (without the option to exchange them) and the requirement for wires to have wooden rims. Eventually, with the format solidified, the popularity of the Tour eventually saw riders from around the world involved in the race, and today the Tour de France is a world renowned sporting event.

Become a part of history

With over a century of incredible highs, world-class riders and a fanbase that is only becoming more passionate, the Tour de France remains a yearly highlight for many.

You too can be a part of the excitement – get in touch with Mummu Cycling today or have a look through our range of tours to find the perfect one for you.

At Mummu Cycling we’ve combined life’s two greatest pleasures: travelling and cycling. There’s no experience more unique than going on a cycling tour. Nothing else gives you the blissful joy of feeling the wind on your skin while breathing in the fresh air of the countryside — something that definitely cannot be said of sitting on a stuffy tour bus. If this sounds like what you’re looking for, then you’ve come to the right place.

- See Our Tours

- Bespoke Experiences

Home > Events > Cycling > Tour de France > Trivia > Firsts

Tour de France Trivia - Firsts

- The FIRST tour de France event was held in 1903 (see history ), won by Frenchman Maurice Garin (see winners list ).

- The FIRST time a rider was awarded the win but disqualified at a later date was in 1904 when the leader was found to have caught a train for part of the event.

- The FIRST Tour that left French territory was in 1906, when the race went into the German territory Alsace-Lorraine.

- The FIRST cyclist to have died during the Tour de France was in 1910 when French racer Adolphe Helière drowned at the French Riviera during a rest day.

- The FIRST time the yellow jersey was awarded was in 1919 (previously a yellow armband was used). The FIRST rider to wear the yellow jersey was Eugène Christophe.

- The FIRST live radio broadcast of the race was in 1929.

- The FIRST time the mountains classification prize was awarded was in 1934. The FIRST time a jersey was awarded to the leader of the mountains classification was in 1975 when the organizers decided to award a white jersey with red dots to the leader.

- The FIRST time trial was held in 1934, between La Roche-sur-Yon and Nantes (80 km).

- The FIRST live TV broadcast was the finish at the Parc des Princes in Paris on 25 July 1948.

- The FIRST time a sprinters points classification was introduced was in the 1953 Tour de France, and was FIRST won by Fritz Schär.

- The FIRST time the Tour started outside France was in 1954: in Amsterdam, Netherlands

- The FIRST time a launch ramp, a sloping start pad for riders, was first used for the time trial was in 1965.

- The FIRST prologue was held in 1967.

- The FIRST time a young rider classification was added to the Tour de France in the 1975 edition, with Francesco Moser the FIRST winner.

- The FIRST time the race finish has been on the Champs-Élysées in Paris was in 1975.

- The FIRST winners of any Tour classifications from outside cycling's Continental Europe was in 1982 when classifications were won by Sean Kelly of Ireland (points) and Phil Anderson of Australia (young rider)

- The FIRST time a women's event was held was in 1984 (and continued until 2009)

- The FIRST non-European winner was Greg LeMond of the USA in 1986.

- The FIRST time the Tour de France was won without winning any individual stages was by Greg LeMond in 1990.

- The FIRST rider to win five times in consecutive years was Miguel Induráin of Spain, first in 1991.

- The FIRST African-based trade team to compete in the tour was MTN-Qhubeka in 2015 (though An Algerian-Moroccan squad rode in the 1950 Tour de France when only national and regional teams were allowed to enter)

Related Pages

- Tour de France Trivia

- History of the Tour de France

Search This Site

More cycling.

- Cycling Home

- Fitness Testing

- Tour de France

- Cyclist Profiles

Major Events Extra

The largest sporting event in the world is the Olympic Games , but there are many other multi-sport games . In terms of single sport events, nothing beats the FIFA World Cup . To see what's coming up, check out the calendar of major sporting events .

Latest Pages

- List of eSports

- Medicine for Weight Loss

- Olympic Flames of the Future

- Sport in Palestine

Current Events

- Paris Olympics

- 2024 Major Events Calendar

Popular Pages

- Super Bowl Winners

- Ballon d'Or Winners

- World Cup Winners

Latest Sports Added

- Kubihiki - neck pulling

- Wheelchair Cricket

- SUP Jousting

home search sitemap store

SOCIAL MEDIA

newsletter facebook X (twitter )

privacy policy disclaimer copyright

contact author info advertising

- Subscribe to newsletter

It's going to be so great to have you with us! We just need your email address to keep in touch.

By submitting the form, I hereby give my consent to the processing of my personal data for the purpose of sending information about products, services and market research of ŠKODA AUTO as well as information about events, competitions, news and sending me festive greetings, including on the basis of how I use products and services. For customer data enrichment purpose ŠKODA AUTO may also share my personal data with third parties, such as Volkswagen Financial Services AG, your preferred dealer and also the importer responsible for your market. The list of third parties can be found here . You can withdraw your consent at any time. Unsubscribe

The Origin Story of the Tour de France

The first Tour de France took place over 100 years ago, back in 1903. Do you know why the race was held and who had the idea for cyclists to go around the whole of France?

The story begins at the turn of the 20th century with two French newspapers competing for readers. The editor-in-chief of the cycling newspaper Le Vélo, Pierre Giffard, held different political views from one of the newspaper’s major patrons, Jules-Albert Dion. They stood on opposing sides of the Dreyfus case. Alfred Dreyfus was an Alsatian Jew who was framed with manufactured evidence and given a life sentence for supposedly passing secrets to the Germans. This issue divided France, the conservative part wanted him sentenced, while progressives wanted him exonerated. Jules-Albert Dion decided to halt his support of Le Vélo and establish a new newspaper called L’Auto-Vélo to drive Pierre Giffard’s Le Vélo out of business.

Henri Desgrange was chosen as the editor for the new L’Auto-Vélo newspaper. Henri Desgrange was a man of many talents, he was a lawyer, cycling promoter, and former competitor himself. He set the first World Hour Record with 35,325 kilometres in 1893. He wrote a successful book about racing, Head and Legs . And he also managed a velodrome that got little mention from Giffard, which was further motivation for him to succeed with L’Auto-Vélo.

In 1900, the first issue of L’Auto-Vélo came out printed on yellow paper to differentiate itself from the green paper of Le Vélo. Le Vélo was quick to sue the new magazine for plagiarism, claiming that they chose a name that was too similar. Le Vélo won the lawsuit and L’Auto-Vélo was forced to rename to L’Auto, the first blow to the new newspaper. As time went on, L’Auto kept losing the battle for sports readership with the more established Le Vélo. They needed something big to attract cycling fans.

In November of 1902, Desgrange called his core staff for an emergency lunch to brainstorm ideas that could reinvigorate the newspaper and give it an edge. Géorges Lefèvre, a writer who was covering cycling and rugby, came prepared.

Géorges Lefèvre: “Let’s organize a race that lasts several days longer than anything else. Like the six-day ones on the track, but on the road. Our big towns will welcome the riders.”

Henri Desgrange: “If I understand you correctly, petit Géo, you’re proposing a Tour de France?”

Géorges Lefèvre: “Yes, why not?”

Henri Desgrange: “I will ask Victor.”

Desgrange apparently took credit for the idea when he proposed the race to the financial controller of L’Auto, Victor Goddet. Goddet, to the surprise of Desgrange, approved the idea, despite the massive costs that would come with it. He understood the promotional value of this epic proposal.

The loss of the plagiarism suit and declining readership gave L’Auto reasons to proceed with speed with the race in order to promote the magazine to cycling fans. The other sports magazines had their own races, but Lefèvre’s idea would completely leapfrog these other races in scope and appeal.

They moved fast and on the 19 th of January 1903 L’Auto announced the biggest cycling race that would span 2,428 km over 6 stages from 31 st May to 5 th July. No assistance, no pacers, no coaches, no masseuses so that all riders have the same conditions.

There were only 15 signups for this monstrous race about a week before the start. Henri acted quick. He moved the start date to the 19 th of July and promised 5 francs per day for the top 50 riders and increased the prize pool to 20,000 francs. Soon, he has a peloton of 60 competitors ready to put on a show, 49 French, 4 Belgian, 4 Swiss, 2 German, and 1 Italian cyclist. Only 21 of these are professional cyclists and many of them aren’t even full-time competitors. Most of the participants are simply adventurers or unemployed.

Henri Desgrange remains sceptical of this whole risky endeavour and stays hidden in the newspaper office on the first day of the race. Géo Lefèvre is the true hero of L’Auto. He follows the whole race, sometimes on a bike himself, other times in a car or catching trains so he doesn’t miss a single checkpoint. He becomes the race director, commissaire, and reporter in one.

The race turns into a sensation. Hundreds of thousands of fans come to the streets to cheer the riders on their gruelling route and over 20,000 are waiting at the velodrome in Paris at the finish line. L’Auto rides the success and nearly triples its readership during the race.

It only takes another year for L’Auto to completely dominate the cycling world with Tour de France’s success and bankrupt its competitor Le Vélo. Pierre Giffard loses the battle of cycling newspapers and his job along with it. It doesn’t take long and Henri Desgrange offers him a position as a cycling reporter in his growing magazine L’Auto.

Articles you might like

Smiles, Sweat and Tears: L’Etape 2024 Had It All

It’s 8:20 in the morning, yet my heart is beating like I have already climbed 5000m. The air is full of excitement. Cheerful chatter fills the air at SAS 11, where cyclists from all around the world mingle, share stories, talk bikes, and tremble with…

Vingegaard Shows Old and New Form and Beats Pogačar in a Sprint

Game on! By winning Wednesday’s grueling stage 11 of the Tour de France, defending champion Jonas Vingegaard (Visma–Lease a Bike) demonstrated that he has recovered from the grave injuries he suffered on the Tour of the Basque Country in April and looks to be, for…

Choosing the Perfect Bike: Insights from Kasia Niewiadoma

As a professional cyclist, selecting the right bike and ensuring it fits perfectly for different races and terrains is crucial for performance and comfort. Today, I’ll share my approach to choosing the best bike, finding the ideal fit, and adjusting to suit specific goals and…

What’s Camping at the Tour de France Like?

Experiencing one of the biggest sporting spectacles in the world in person is something special. And there’s no better place to make it a truly memorable experience than on the top of a mountain. If you’ve ever wondered what camping to see a mountain stage…

Home Explore France Official Tourism Board Website

- Explore the map

The 5-minute essential guide to the Tour de France

Inspiration

Cycling Tourism Sporting Activities

Reading time: 0 min Published on 8 January 2024

It is the biggest cycling race in the world: a national event that France cherishes almost as much as its Eiffel Tower and its 360 native cheeses! Every year in July, the Tour de France sets off on the roads of France and crosses some of its most beautiful landscapes. Here’s everything you should know in advance of the 2018 race…

‘La Grande Boucle’

In over a century of existence, the Tour has extended its distance and passed through the whole country. Almost 3,500 kilometers are now covered each year in the first three weeks of July, with 22 teams of 8 cyclists. The 176 competitors criss-cross the most beautiful roads of France in 23 days, over 21 stages. More than a third of France’s departments are passed through, on a route that changes each year.

A little tour to start

The first ever Tour de France took place in 1903. It had just six stages – Paris-Lyon, Lyon-Marseille, Marseille-Toulouse, Toulouse-Bordeaux, Bordeaux-Nantes and Nantes-Paris – and 60 cyclists at the start line. At the time, the brave cycled up to 18 hours at a stretch, by day and night, on roads and dirt tracks. By the end, they’d managed 2,300 kilometers. Must have had some tight calves!

Mountain events are often the most famous and hotly contested. Spectators watch in awe as the riders attack the passes and hit speeds of 100 km/h. In the Pyrenees and the Alps, the Galibier and Tourmalet ascents are legendary sections of the Tour, worthy of a very elegant polka dot jersey for the best climber…

The darling of the Tour

In terms of the number of victories per nation, France comes out on top, with 36 races won by a French cyclist. In second place is Belgium with 18 wins, and in third is Spain with 12. The darling of the Tour remains Eddy Merckx, holding the record of 111 days in the yellow jersey. This Belgian won 5 times the Great Loop as Jacques Anquetil, Bernard Hinault and Michael Indurain.

‘Le maillot jaune’

The yellow jersey is worn by the race winner in the general classification (calculated by adding up the times from each individual stage). This tradition goes back to 1919. It has nothing to do with the July sunshine or the sunflower fields along the roads; it was simply the colour of the pages of newspaper L’Auto, which was creator and organiser of the competition at the time.

The Tour de France is the third major world sporting event after the Olympic Games and the World Cup, covered by 600 media and 2,000 journalists. The race is broadcast in 130 countries by 100 television channels over 6,300 hours, and is followed by 3.5 billion viewers.

The Champs-Élysées finish

Each year the Tour departs from a different city, whether in France or in a neighbouring country. Since 1975, the triumphal arrival of the cyclists has always taken place across a finish line on Paris’ Champs-Élysées. It’s a truly beautiful setting for the final sprint.

And the winner is…

Seen from the sky and filmed by helicopters or drones, the Tour route resembles a long ribbon winding its way through France’s stunning landscapes: the groves of Normandy, the peaks of the Alps, the shores of Brittany and the beaches of the Côte d’Azur. In 2017, it was the Izoard pass in Hautes-Alpes that was elected the most beautiful stage, at an altitude of 2,361 metres. Which one gets your vote?

Find out more on the official Tour de France site: https://www.letour.fr

By France.fr

The magazine of the destination unravels an unexpected France that revisits tradition and cultivates creativity. A France far beyond what you can imagine…

Get in touch with Nouvelle-Aquitaine in South West of France

Biarritz-Basque Country

Loire Valley, Champagne and beyond, The perfect blend

Alsace and Lorraine

Paris Region is the home of major sporting events!

Tour de France : Final stage of glory in Paris

Cycling, a new key to the coastline.

Along La Loire à Vélo

Loire Valley

Discovering the most beautiful beaches of the Pays de la Loire, by Natigana

#ExploreFrance

Atlantic Loire Valley

Fly, Walk, Pedal - Get Moving on the Côte d'Azur

Côte d'Azur - French Riviera

A brief history of the Tour de France

The Tour de France is an annual cycling spectacle held primarily in France. But how did it start? Why does the leader wear a yellow jersey? Here is a brief history of the race from the Cicerone guidebook to Cycle Touring in France.

The first Tour de France

The first Tour de France – the world’s greatest bicycle race – took place in 1903. Created by Henri Desgrange, the editor of L’Auto, and George Lefèvre, the rugby and cycling reporter, to help publicise and improve circulation of this sports newspaper, the first event was a six-stage race covering 2428km. The riders left Paris for Lyon, then cycled on to Marseille, Toulouse, Bordeaux, Nantes, and finally back to Paris. The average stage distance was 405km, which meant the competitors had to cycle nights as well as days! They also had to carry out their own repairs if necessary.

Cycling the Route des Grandes Alpes

Cycling through the french alps from lac leman to menton/nice.

Guidebook to cycling the 720km Route des Grandes Alpes through south-eastern France. From Lake Geneva to Mediterranean Nice via numerous high Alpine passes, taking in the Vanoise, Écrins and Mercantour National Parks, the route is challenging, although entirely on roads. However, with plenty of charging points, it is well suited to eBikes.

Maurice Garin won that first Tour in front of 20,000 Parisiens, and L’Auto’s circulation quadrupled, heralding the birth of something very special. Yet the following year’s Tour was almost the last, with many riders cheating by catching trains on occasion and even sabotaging each other’s bicycles. Fortunately the organisers decided to stage the race again in 1905 with more concrete rules and they introduced the first mountain stage, the Ballon d’Alsace. Desgrange added a stage through the Pyrénées in 1910, and one in the Alps a year later. By now the Tour had more than doubled in overall distance and number of stages, but the average stage distance was still frighteningly long at 356km.

The yellow jersey

Immediately after World War I Desgrange introduced the yellow jersey (maillot jaune). He chose this colour for two reasons: the roadside spectators could pick out the race leader easily and, perhaps more significantly, L’Auto was printed on yellow paper. Eugene Christophe was the first man to don the yellow jersey on 18 July 1919. The first Italian to win the Tour – previously dominated by the French and Belgians – was Ottavio Bottecchia in 1924. He notched up another victory the following year.

The longest-ever race in Tour history took place in 1926, covering a total distance of 5745km. Such monstrous rides had become a thing of the past by the early 1930s when the Tour was opened to other advertisers, coverage was broadcasted live on the radio, and French riders won the race six years in a row. In 1937 the first derailleurs were allowed in the Tour de France. A year later the Italian cyclist Gino Bartali won the Tour, then won it again 10 years later in 1948 at the age of 34. Bartali was physically assaulted on the Col d’Aspin in the Tour of 1950, but went on to win the stage before he and his Italian team-mates (including Fausto Coppi, the 1949 victor) withdrew in protest.

Tough climbs and tragedy

Two of the toughest climbs of the Tour de France were introduced in the early 1950s: Mont Ventoux in 1951 and l’Alpe d’Huez in 1952. Coppi won the first historic stage of l’Alpe d’Huez, and then went on to win the Tour that year. French riders, including Louison Bobet and Jacques Anquetil, dominated the next five Tours, and the great Spanish climber Federico Bahamontes won the 1959 event. Anquetil went on to win four consecutive Tours between 1961 and 1964, becoming the first of only five riders to notch up more than three victories to date. The Tour’s most recent tragic fatality occurred in 1995, when Fabio Casartelli crashed at 88 km/h (55 mph) while descending the Col de Portet d'Aspet, while previously in 1967 Tom Simpson collapsed near the summit of Mont Ventoux, and Francesco Capeda died on the Galibier in 1935.

The Belgian Eddy Merckx became the second man to win five Tours (1969, 1970, 1971, 1972 and 1974), subsequently matched by Bernard Hinault (1978, 1979, 1981, 1982 and 1985). Laurent Fignon, winner of two Tours, and Greg Lemond, the first American to win a Tour in 1986, battled against each other for victory in Paris in 1989. It came down to the final time-trial in the capital, which Lemond famously won by the slimmest of margins in the history of the Tour de France: 8 seconds! The 2017 Tour has set most of the General Classification contenders within seconds of each other for much of the three week race.

The early 1990s belonged to one man in particular, Miguel Indurain. He won five Tours in a row from 1991 and 1995 and, like Lemond, was strong in all disciplines.

The rise and fall of Lance Armstrong

During Indurain's reign another American was emerging; Lance Armstrong won a stage in the 1993 and 1995 Tours. Diagnosed with testicular cancer in 1996, Armstrong was given a slim chance of living, since it had also spread to various parts of his body and brain. Following an operation and painful chemotherapy, he fought back with a vengeance and won the 1999 Tour de France. He never looked back, joined the élite club of Anquetil, Merckx, Hinault and Indurain by winning five Tours... and then went two better. However, he had these winnings stripped after a lengthy doping investigation.

British winners of the Tour

Despite, ahem, a slow start, Britain has, in recent years, become a major player in the Tour. Brits have dominated since Bradley Wiggins of team Sky became the first British rider to win in 2012. After "Wiggo" broke the lengthy losing streak Chris Froome has won the Tour four times, in 2013, 2015, 2016 and again in 2017.

Sprinter Mark Cavendish , known as 'the Manx Missile' from the Isle of Man, holds the record for the most mass finish stage wins with 30 as of stage 14 in 2016.

- Cycling and cycle touring

Cycling London to Paris

The Rhine Cycle Route

The River Rhone Cycle Route

Cycling the Canal de la Garonne

The Moselle Cycle Route

Walking the Brittany Coast Path

Cycling classic Tour de France climbs

A trail of two cities: A cycle route from London to Paris

An intro to… The Via Podiensis or The Way of St James (the GR65)

The River Loire Cycle Route: ultimate planning guide

The Velo Francette - France's newest long-distance cycle route

Tour de France

Giro d'italia women (giro donne), tour de l'ain, mtb eliminator world champs - aalen, tour of wallonie, arctic race of norway, vuelta a burgos, clásica san sebastián femenina, clásica san sebastián, circuito de getxo, tour de france femmes avec zwift, tour de pologne, tour du limousin, tour of denmark, on this day in 1902, the idea for the tour de france was born, in the offices of a struggling french sports paper 115 years ago — november 20, 1902 — the idea for the tour de france was first born..

In the offices of a struggling French sports paper 115 years ago today — November 20, 1902 — the idea for the Tour de France was first born.

The paper, L’Auto, was suffering from poor circulation, and desperate for ideas to prop up sales. At an emergency meeting with the paper’s editor, Henri Desgrange, a young journalist named Géo Lefèvre blurted out the idea for a multi-day bike race around France.

At the turn of the century, bike racing was one of the world’s most popular sports. But bicycle stage racing didn’t exist prior to the first Tour de France, which was subsequently held that July in 1903.

The race was a success. By 1908, L'Auto's circulation had increased tenfold, from 25,000 to more than a quarter million.

Desgrange, a former racer racer himself — he held the first hour record ever recorded — went on to become the self-proclaimed “father of the Tour," immortalized in history books as the man responsible for one of modern day sports most well-known events.

Yet, let us not forget Lefèvre, who was under pressure to dream big, and imagined Le Tour.

Related Content

Jul 10, 2024

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

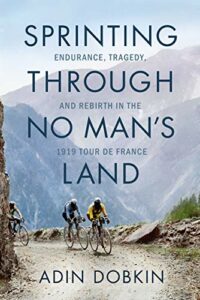

How a Small French Newspaper Began the Tour de France

Adin dobkin on l'auto , the war torn year of 1919, and the beginning of the legendary bike ride.

Henri Desgrange watched the celebrations pass by on rue du Faubourg Montmartre. Crowds renewed themselves along the blister of a road through Paris’s ninth arrondissement, on the Seine’s right bank. The editor stood, stiff. His soldier’s posture had not yet left him. When he’d held his unit’s colors, his face set for the army photographer, it had taken effort to stay as rigid as his soldiers, three decades younger than Desgrange. Anyone who knew him would say he thought nothing of the gap in their ages.

Stasis didn’t suit him. Desgrange always appeared in constant motion: his white hair swept back over his still dark, wayward brows, his chin cocked out, his eagle nose just barely upturned, as if to focus on some prey. He had watched his neighborhood dim in the preceding years, though that day it was, for at least a moment, reborn. The powder-blue dressing rooms and gilt mansions of les Grands Boulevards, their extravagant rose gardens concealed behind modest steel fences, all remained a short walk away, but the artists who had once made their homes nearby had moved to the city’s left bank and carried Paris’s cultural mass with them.

The occasional salon and cabaret still opened its doors on fall evenings like this one, however, and new jazz clubs had moved into the shuttered spaces between, buoyed by the unending tide of the city. Desgrange, the editor-in-chief of the sports daily l’Auto, could look out his office window and see the corridor that led to Bouillon Chartier’s entrance where waiters scribbled out customers’ receipts on unfussy paper tablecloths. He’d sometimes take his journalists to the restaurant after editorial meetings, when a walk to boulevard Montmartre felt too far with the evening’s deadlines. If he turned his head to the left, he could just make out the second-story awning of Gaumontcolor. The cinema’s neon lights cast a faint glow on the opposite wall; geometric shapes snapped in and out of existence on the pavement underfoot.

Anyone waiting outside the theater that day was subsumed by the passing bodies who crowded the Faubourg Montmartre street. Few were willing to miss the celebrations that continued into the late afternoon. For the first time in years, the streetlights remained lit as the evening aged but did not wane; they cast a glow on the people’s newly freed movements well into the night.

Parisians, Americans, British, Belgians—most anyone who found themselves in the French capital—amassed on the streets that day to celebrate the armistice signed between the Allied countries and Germany. They arrived knowing the fighting on the western front had ended at 11:00 am, though most who crowded onto the avenues had not yet heard what the document’s terms were. Whatever clauses and subclauses had been agreed on by their leaders and those on the table’s opposite side mattered little to the people’s immediate celebrations: it was enough that the thing was through.

No matter the conditions of the armistice, no matter how much Germany paid for those four years, the document couldn’t make up for the war’s cost. Like the rest of France, Desgrange had been consumed with the war. It had stamped his existence, left no corner un-inked. And his country? The war had threatened to tear it from its foundation, to cart off its remains, to expand Germany’s excision of territories and to break apart the alliance France had formed with Great Britain.

he country’s borders had not collapsed any further in the war—they’d expanded—but the conflict had succeeded in its first aim: to uproot the ground in tracts of land to Paris’s northeast. In doing so it shattered those young men, and plenty of old ones, too. Men who had been sent away in those first days of fighting with spirit in excess. Their stamina hadn’t lasted as long as the war did. Those men couldn’t be blamed; they had volunteered for a tragedy few had expected or prepared for, even those who led the aggressors.

A few saw how war had changed in the 60 years before 1914, in the cast artillery guns and industrial train tracks that ran like roots behind units in the Crimean War and in Vicksburg’s trench networks in the American Civil War. The Great War revealed those logistical and engineering lessons as ruinous, if inevitable, advances to warfare. Little could have protected the men on the front, short of killing every last German who had stepped onto their country’s trampled ground. Underfoot, the land carried each side. It held as they advanced and retreated, back and forth, but after four years it was broken: its roads dredged up and its farmlands and forests fallow. Negotiating with German generals and politicians might have spared lives, but after the war had slowed, burrowed into the clay, no conversation could have brought back those poilus Desgrange had funneled through l’Auto’s offices.

Desgrange paused. His fingers hovered over the keys. The paper’s founding message, written by him and published in l’Auto ’s first issue on October 16, 1900—19 years ago—said the newspaper would avoid political issues, in contrast to its many competing sports dailies. He and l’Auto ’s advertisers had seen an opportunity to differentiate themselves from Le Vélo , their widest-circulating opponent, whose writers and editors regularly waded into domestic political conversations. Le Vélo ’s editor-in-chief, Pierre Giffard, had come to the defense of Alfred Dreyfus in its pages, to the chagrin of Le Vélo ’s conservative advertisers. Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, had been convicted of selling military secrets to the Germans.

At the time of Giffard’s defense, those who supported Dreyfus hoped to reopen his case and overturn the conviction, while anti-Dreyfusards thought that doing so would weaken people’s faith in France and its government. An antisemitic undercurrent ran throughout. At the time of the affair, Desgrange was a public relations representative of Clément-Bayard automobiles, itself a Le Vélo advertiser. He had already left his days as a professional cyclist behind. He had not broken from the sport entirely, though.

Only a few years before he had become the director of Parc des Princes, an arena with a cycling track in the city’s western suburb of Boulogne-sur-Seine. Desgrange wrote articles and opinion pieces about physical education and sports for Le Vélo and other publications outside his regular public relations duties. As the Dreyfus Affair continued, he remained publicly mute, a quality that appealed to his employer, Adolphe Clément-Bayard.Soon after Giffard declared his support of Dreyfus in his newspaper’s green-tinted pages, Clément-Bayard, the founder of the company bearing his name, brought Desgrange into discussions between Le Vélo ’s advertisers. Clément, like the other corporations who advertised in the paper, had publicly disagreed with Giffard’s slant in Le Vélo ’s coverage. Clément and the others had pulled their advertisements in protest. They had little desire to return that money to Le Vélo anytime soon.

Instead, they hoped to create a competing sports daily that would sate the public’s interest in athletics without the political coverage that had fragmented readership. Clément believed Desgrange could be an ideal editor for the new paper: he was a cyclist who had achieved some public acclaim after setting records in the hour, the 50 and 100 kilometers, and the 100-mile lengths on bicycles. He had written columns and books on his own experiences. As a public relations manager, he knew how to deal with journalists, even if he wasn’t one himself. The advertisers didn’t want to consider anyone else for the job; they offered the editor-in-chief position to Desgrange. He accepted.

L’Auto ’s founding message well represented its early stance toward politics, even before the war broke out. “What we wanted to say is said,” Henri wrote to l’Auto ’s readers of the Dreyfus Affair, though the paper had said nothing until that point. He didn’t comment on Dreyfus again. The advertisers of the new sports daily, yellow tinted in contrast with Le Vélo ’s green, were satisfied with their investment.

L’Auto ’s founding and the Dreyfus Affair were far from Desgrange’s mind that November evening. His enemies, those his readers and advertisers shared, weren’t fellow Frenchmen but foreigners. He saw little chance a civil war would erupt between his fellow citizens who hated the Germans and those who thought they were being treated too harshly in their defeat. The few who believed that were in the minority and most were smart enough to recognize it and watch their own language. Le Vélo had shuttered in 1904 and the war had created a common enemy, one all of Paris could agree upon—Desgrange was free to write as he pleased.

Given the celebrations on most every Paris street, in countless small towns on the city’s outskirts, and in trenches that had been rendered worthless, l’Auto ’s major advertisers like Jacques Braunstein at Zig-Zag and the Palmer Tire executives wouldn’t mind their ads abutting another of Desgrange’s political columns. They had remained loyal to the editor over the years. They had trusted him to expand the newspaper’s circulation in its first years as it competed directly with Le Vélo , and had stuck by him once Le Vélo had closed, quotas on materials had restricted l’Auto ’s coverage, and its reporters—fighting-age men—had been called to the front. The newspaper’s readers had more pressing concerns than what l’Auto covered, cycling and gymnastics, running and yachting. But the sporting events Desgrange and his correspondents wrote about, those that continued in the wartime years, provided those readers with a release from the events that filled the pages of other newspapers: the movements of battleships, the arrest of foreign spies not far from where they lived, the deployment of units filled with sons, husbands, and fathers.

In l’Auto ’s early days, Desgrange worked to live up to his advertisers’ initial confidence. His public relations experience, however, hadn’t carried him far in the newsroom. He had few ideas for stories and didn’t have much knowledge on how to manage a team of journalists. He only followed what others in the industry did and hoped the absence of something—political coverage—would be enough to drive readers to l’Auto . His brash writing hid a caution in business manners: whenever possible, he preferred others take risks in developing new projects while he waited to see whether their ventures would pay off. Given that plenty of other sports dailies were still in the market, even after Le Vélo faltered, l’Auto ’s circulation stalled in those first years. The newspaper’s future had been uncertain enough that Desgrange’s job had been threatened. The advertisers expressed their hope he would turn things around, a sign that anyone without his relationships would have already been fired from the job. The threat wasn’t enough to change Desgrange’s nature, but it at least opened him to others’ ideas.

Desgrange held an editorial meeting in response. He asked the journalists who worked under him and those administrators on the business side of the paper for their ideas on how l’Auto could grow its subscription base. Géo Lefèvre, a 26-year-old cycling and rugby correspondent whom Desgrange had hired away from Le Vélo , spoke up. Lefèvre’s previous employer had sponsored sporting competitions and provided exclusive coverage of the results: Paris–Roubaix, Bordeaux–Paris, Paris–Brest–Paris. The three were one-day cycling events that Le Vélo helped organize and run. By offering readers exclusive interviews with the contestants and by following the cyclists on each section of road, Le Vélo encouraged nonsubscribers to pick up the paper on race days. Some, they hoped, would even subscribe after seeing the surrounding reporting.

The one-day cycling races worked well for the newspaper’s aims: the races didn’t require much in the way of logistics and took place on regular roads instead of in stadiums—for-profit companies themselves that would have their own ideas about coverage. The events appealed to competitive cyclists but also attracted amateurs. Races any longer than one day would be difficult for cyclists who didn’t train for endurance. On a longer race, registrants would flag, but the sponsoring newspaper could extend the days it offered in-depth coverage. More adventurous than Desgrange, with less to lose, Lefèvre suggested a cycling race longer than anyone before had considered, one spanning France’s entire border. “A Tour de France,” Desgrange clarified.

The Tour had existed as part of French life even if it had never been a cycling race. Kings went on tour to inspect their more distant lands, to let those with tenuous allegiances know that they remembered them; craftsmen left their hometowns for tours to learn how others in regions not their own built cathedrals, baked pastries. Le Tour de la France par deux enfants , a book French children read in primary school, described two children’s journey around their country to find their uncle. A Tour de France race on bikes had never been considered, but it could be imagined. It was enough for Desgrange to not dismiss Lefèvre’s idea immediately.

The editor took the journalist to a café after the meeting and discussed the proposed race further. The pair decided Desgrange would bring the idea to l’Auto ’s business director and cofounder, Victor Goddet, for his input. If Goddet thought it impossible, that was easy enough: the idea wouldn’t go any farther. When Desgrange went to him, however, Goddet thought it was just what l’Auto needed.

The Tour de France’s first years surpassed Desgrange’s guarded expectations. People left their homes to watch the cyclists on the 1903 Tour’s six stages. In time, the Tour route extended, hewed closer to France’s borders. The cyclists beat the bounds of their country. They marked France’s borders and every town they rode through, in each new clime they reached. As the cyclists biked through some of the same small towns in subsequent years, the association between that town and the Tour grew. The towns formed the Tour, and the Tour formed the towns as well as the country.

Many cyclists didn’t find the Tour appealing at first. It was unquestionably more difficult than one-day events with relatively large purses for the cyclists’ investment of time and training. The Tour was a challenge as much as a race. The average professional didn’t know whether they could finish until they rode back to Paris. Sponsors still promised cyclists’ salaries for the competition, however, and with the smaller prizes along the way, racers could justify the effort. L’Auto and Desgrange’s job were saved. Near the Tour’s end, l’Auto ’s circulation ballooned, multiples of Le Vélo ’s on its best days. The competing paper shuttered in 1904. Desgrange even became comfortable with the race he had once considered a gamble. He had made it part of his image: the father of the Tour de France. It was his foresight, after all, that let it occur those first years, before its concept had been proven. Géo Lefèvre—who had conceived of the race—was transferred to writing about boxing and aviation while Desgrange stayed involved with the Tour’s administration, covering it in regular dispatches as he followed its route.

On the day of the 12th Tour’s start, June 28, 1914, the archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo. The cyclists were already on the road to Le Havre when Gavrilo Princip fired two shots into the archduke’s car. They rode on even after they heard the news. The race ended on its scheduled day of July 26th. On August 3rd, France entered the war; Tour winner Philippe Thys’s Belgium had already been invaded by that time. With the news, plans for the thirteenth Tour—the event that had saved l’Auto from failure—halted. The race couldn’t hope to cycle along the country’s borders.

Desgrange and the paper couldn’t afford to stagnate until the war had ended, even if the Tour couldn’t take place. L’Auto continued to cover life and sport during the wartime years, even as one after another major sporting event was canceled or held with smaller crowds and diminished competitors. In his columns, H. Desgrange was replaced by H. Desgrenier , a thin pseudonymous veil. The paper’s founding promise of reporting unaffected by politics fell away with the other vestiges of the prewar landscape.

Desgrange’s columns darkened. “This is our work!” he began in his August 15th column, just before Desgrange had turned into Desgrenier. German politicians “alone are amazed to see France draw up against the German brute, they who haven’t bothered to study, for twenty years before the war began, our moral and physical evolution.” He barely distinguished between German leaders and German men who had been conscripted in the fight against France. He continued writing columns supporting France’s decision to fight as the war went on, when his country’s prospects were dim and plenty of other Frenchmen were supporting politicians’ few attempts to resolve the war quickly and peacefully. He continued after he volunteered for the military in April of 1917, at the age of fifty-two, sending his columns back by post. He only let a few close friends and his mistress know his decision. He privately hoped to carry out the mission he had been writing about since the war’s start, to do his part in reclaiming the French lands that had been lost after the Franco-Prussian War and to fight the Germans who would have his country reduced even further.

L’Auto ’s front page was at times a small altar to former Tour competitors. The name of a cyclist from the 1914 edition of the race would appear. “Lapize falls on the field of honor,” “Death of Lucien Petit-Breton: the end of a great champion—the accident—his main victories.” In the editor’s bold pen, cyclists who had died in the war were memorialized. Those reading the obituaries were safe behind the lines, celebrating in Paris while their country’s heroes had been brought down in the war. They should remember them, Desgrange wrote in his columns, celebrate them, do anything but forget them.

He ended the obituary of Octave Lapize, the 1910 Tour champion, who had been shot down eight kilometers behind French lines in a dogfight, with one last proclamation: “Hourlier, Comès, Faber, Bouin, Engel! And now Lapize!” he wrote, listing the cyclists killed in the war. “O heroic dead, victims of this Teutonic barbarism, receive splendidly this beautiful son of superb France. He will be, like you, worthily avenged!” Three winners of the Tour had been killed in the war; others had been maimed. Countless not-yet professionals and aspirants who might have someday competed in the race died in the front’s churn.But the war had ended, and the crowd outside l’Auto ’s office flocked past.

The people of France, or at least those who read him, had come to expect something from Desgrange: a salve for those preceding years, someone who recognized the hardships they had gone through, would continue to go through, who wasn’t afraid to place blame for those hardships. He was a voice of confidence who could direct their attention, someone who recognized, knew personally, the costs they had endured and the spirit that had stayed with them despite the war’s toll. He couldn’t disappoint them by letting its end pass without comment.

”Ah! My dear country, what suffering we’ve paid to purchase your resurrection,” Desgrange typed. “And what funeral hours next! What grief! The despair we had when the German brute took advantage of us with his methodical planning!” Desgrange drew his conviction from the same source he had found those years back, at the war’s outset, when he’d told French boys to not take mercy on the German soldiers but to shoot them where they stood. “Let us draw a line. Let us live.” He paused once more. “Goodbye to the Boche, and hello to your home!” Desgrange knew some towns along the front would need to be rebuilt entirely. The land around them might never be useful again. Local politicians and whoever chose to return home might find new uses for the fallow ground—more factories, perhaps, like those that had sprung up far from the trenches, supplying the battle lines with all they needed. Bricks or cement could pave over the cratered landscape. People might be able to turn those onetime towns into bustling cities that could supply new factories with the workers they would need. Or the land might stay as it was that day, a memorial spanning hundreds of kilometers where visiting crowds could look in from its edges, few desiring to intrude any farther.

Some towns—Ailles and Courtecon, Moussy-sur-Aisne and Allemant, Hurlus and Ripont and Nauroy and others—were given to the war as martyrs. The government had already deemed them irreplaceable, at least in physical terms. Next to nothing stood where streets once ran through their center. The towns, politicians decided, could be moved elsewhere; they could be re-created with old plans and local memories—whose house stood next to the butcher, which town hall features should be preserved and which were always complained about, and so on—but they couldn’t exist where they once had been. At the Meuse–Argonne, Desgrange had witnessed that putty knife of the war, flattening the landscape and whatever features had once existed. The people wouldn’t leave the war behind; nothing could cause them to do that, not entirely. But maybe their eyes could be directed elsewhere, at least for a time. Let them see that the scarred country still had its strength, its élan, even if that sinew was not what generals thought it to be in the war’s first days.

Nine days had passed since the armistice’s signing. The November 20th edition of Le Temps arrived on newsstands in the morning fog. Headlines said that on Thursday, the German naval fleet would likely be surrendered to the Allies, barring any delays. On the newspaper’s final page, between advertisements for the bookstore Berger-Leverault and Vin de Vial tonic, the editors noted small events not worthy of including on the front page. In two days, poet Jean Richepin would hold a lecture on American life at the Sorbonne; the Société de Auteurs held their general assembly the evening before; the Maisons Laffitte horse track on Paris’s outskirts would enter the final week of its annual season. Small bits of lifelike grass on tilled ground broke through. These scraps were marginal, but they at least existed. Pronouncements and congratulations from liberated towns decorated its borders. Proclamations from foreign leaders, congratulating the French for all they’d done for the world, filled whatever space remained.

Paperboys unbundled and stacked the daily edition of l’Auto at newsstands. An article discussed how Henry Farman, a French airplane designer, had revealed plans for an aircraft that could transport twenty people in its hollow fuselage. The Six Days of New York bicycle race—scheduled to take place in Madison Square Garden December 2nd to 7th—would return after being canceled in the preceding years. Organizers hoped this year’s race could reclaim just some of its previous glory. Robert Dieudonné penned a new short story, “Pot of Varnish,” which Desgrange published. The editor-in-chief’s column appeared on the center of the front page. It still carried the byline H. Desgrenier . The article concerned the project Desgrange had worked on during the war, before he had volunteered for the front: national physical fitness. An announcement, written in fine print to accommodate its lengthy contents, took up the two rightmost columns of the front page and extended four more onto the second. It described plans for an upcoming race, what documents interested cyclists would need to register, their arrival locations in various cities, and the itinerary of what had already been an ambitious race, in what was bound to be, according to Desgrange, its most ambitious edition.

____________________________________________

Excerpted from Sprinting Through No Man’s Land by Adin Dobkin. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Little A. Copyright © 2021 by Adin Dobkin.

Adin Dobkin

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

A history of foreign starts at the Tour de France

As Copenhagen marks the 24th foreign Grand Départ, we take a look back at memorable starts through the years

Friday's Tour de France Grand Départ in the Danish capital of Copenhagen will mark the 24th time the race has kicked off with a start outside of its home country, a tradition dating back all the way to 1954.

The 2022 Tour start will be the most far-flung yet, even if it doesn't quite match up to the Giro d'Italia's starts in Greece and Israel over the years. It's the first time the race – or any Grand Tour – has started in Denmark.

Over the past 68 years, the Tour has begun in almost every major western Europe country, barring Italy (which could host the 2024 Grand Départ ). The likes of Switzerland, Ireland, Germany, and Spain have all hosted Tour starts in that time.

This weekend, the peloton will take in three stages in Denmark, with a time trial and two sprints on the menu before they fly back to the north of France on Monday. Ahead of the 2022 start and all the action that lies ahead, we've taken a look back at some of the most memorable Grand Départs of years gone by.

1954: Amsterdam, Netherlands

The 1954 Tour would eventually be won by Louison Bobet, the second victory of the first Tour three-peat. The Frenchman was already on the podium on stage 2, winning as the peloton raced from the Flemish city of Beveren to Lille in northern France.

A day earlier, the race had kicked off in Amsterdam, where Dutch rider Wout Wagtmans gave the home crowds something to celebrate as he took the second of four career stage victories at the race just over the Belgian border in Brasschaat.

Massive crowds lined the roads for the opener, which saw Wagtmans attack to the win late on, just about holding off the peloton. He would hold yellow for three days before ceding it to Bobet, and later enjoyed another four days in the lead as the race snaked down to the Pyrenees. (DO)

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

1973: Scheveningen, Netherlands

Joop Zoetemelk had already stood on the final Tour de France podium on two occasions before he had the opportunity to start the 1973 Tour – his fourth – at home, just minutes away from his hometown of The Hague.

He hadn't won a stage of the race by this point, having already accrued two runner-up spots in addition to his two overall second places, but pulled out all the stops on home ground for the short 7.1km prologue.

Under 10 minutes after setting off, Zoetemelk would have his first career Tour stage win, getting the beating of 'the eternal second' Raymond Poulidor by just one second.

He'd end the race fourth overall, and would have to wait seven more years to seal the yellow jersey, while the 1973 race spent three more (half) stages working its way across the Netherlands and Belgium, including a mini 12.4km time trial. (DO)

1987: West Berlin, Germany

By the late 1980s, the Tour was regularly visiting neighbouring countries for Grand Départs, with three in the Netherlands, two apiece in Belgium, and West Germany, and one in Switzerland.

1987 brought a third start in West Germany, and what would be the final visit to the country before reunification. It would be the most far-flung Tour start at the time, and there would be a full five days of racing in Germany before the race even hit the border and returned to France.

A 6km prologue on the opening day brought glory for Dutchman Jelle Nijdam, who utilised two disc wheels to take the win by three seconds as eventual race winner Stephen Roche rounded out the top three.

Nijdam's countryman Nico Verhoeven won stage 1, sprinting home from a small breakaway group, while Roche's Carrera Jeans squad beat Saronni's Del Tongo in the stage 2 time trial.

Portuguese rider Acácio Da Silva and solo breakaway man Herman Frison won stage 3 and 4 into Stuttgart and Pforzheim before the race headed to Strasbourg on stage 5, concluding what would be the last Grand Départ in Germany for three decades. (DO)

1992: San Sebastián, Spain

While the Vuelta a España was at this point in the midst of what would be a 33-year avoidance of the Basque Country (the race returned in 2011), the Tour chose the region to host its first Spanish Grand Départ three decades ago.

The prologue was overshadowed by a bombing in an underground car park in Fuenterrabia the night before, a reminder of the tensions in the region that saw the Vuelta stay away.

The race itself, however, went off without any such problems, and was instead a celebration of reigning champion Miguel Indurain, who hailed from the town of Villava in the eastern Basque Country.

The Banesto leader duly pleased the home crowds with a victory in the 8km prologue, beating ONCE's Alex Zülle by two seconds. Indurain would cede the lead to the Swiss rider on the first road stage a day later, though he'd be back in yellow in the Alps en route to a dominant four-minute overall victory. (DO)

1998: Dublin, Ireland

The 1998 Tour start in Ireland was not completely overshadowed by the Festina scandal that almost caused the entire race to grind to a halt, but the storm clouds were looming fast.

Festina soigneur Willy Voet had been arrested earlier that week on the French border with a trunkload of doping products in his car, the team had already gone into full denial mode over his whereabouts, and riders were already pouring their doping products down the wash-basins and toilets of their hotels.

Given the meltdown that then unfolded in that Tour, with the glorious gift of hindsight it almost seemed irrelevant that Chris Boardman claimed his third Tour prologue win in five years on a rain=soaked Dublin Friday evening. Or indeed that Boardman, while in the leader’s jersey, then crashed out en route to Cork and the ferries assembled to take the race back to France that evening.

But at the time, the massive crowds that lined the route in Dublin despite the weather, and again on the stages taking the race inland that followed, seemed to hold out hope that the Tour start in Ireland would be remembered as a success. But that was all quickly eclipsed by what unfolded in France. (AF)

2007: London, United Kingdom

Pre-empting the British cycling explosion that saw the founding of Team Sky, the 2012 Olympic Games, and the rise to superstardom of Mark Cavendish, Bradley Wiggins, Geraint Thomas, and Chris Froome, the Tour headed to Britain for the first time 15 years ago.