The Prospects for an IP Waiver Under the TRIPS Agreement

By Duncan Matthews and Timo Minssen

The informal meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Council today, July 6, 2021, focuses international attention once more on prospects for a waiver of the TRIPS Agreement in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regardless of whether an actual TRIPS waiver ultimately comes to pass, the real significance of these efforts lies in the increased focus they have placed on the role of IP and trade secrets in improving access and affordability, and scaling-up of manufacturing and supply of vaccines and other health-related technologies. These conversations have introduced the possibility of a rethinking of the relationship between IP, innovation, conservation, and access.

The proposal for a TRIPS waiver, made initially by India and South Africa last October, was given additional impetus on May 5, 2021 when United States Trade Representative Katherine Tai announced that the U.S. supports a waiver for COVID-19 vaccines and will actively participate in text-based negotiations at the WTO to make that happen.

Since then India, South Africa, and their supporters issued revised draft text on May 25, 2021, which would waive (for an initial period of three years) IP on all relevant health products and technologies, including diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccines, medical devices, personal protective equipment, their materials or components, and their methods and means of manufacture for the prevention, treatment or containment of COVID-19.

On June 4, 2021, the EU issued its own proposal , which focuses not on an IP waiver, but instead calls for limits on export restrictions, voluntary measures to encourage and support vaccine production and affordability, and the use of voluntary licenses as the most effective instrument to facilitate the expansion of production and sharing of expertise.

These proposals differ in the details, but share a common goal. They are both broad-based calls to find solutions to the complex question of how best to scale up manufacturing and supply, while improving access and affordability, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

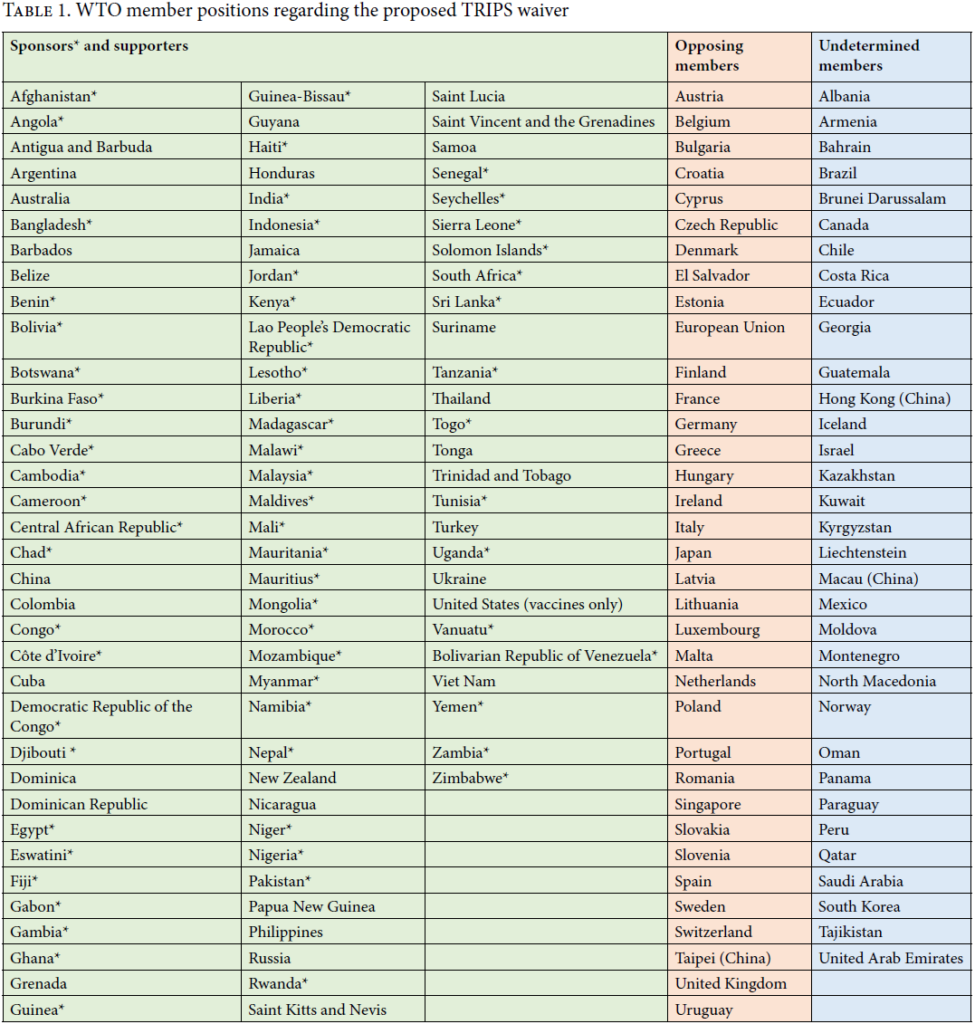

Ultimately, however, the WTO is a member-driven institution, and agreement on a TRIPS waiver will require either consensus, or, if it were to go to a vote, a three-fourths majority in accordance with Article IX of the WTO Agreement . Currently, WTO members supporting the waiver simply don’t have the numbers to achieve this. About 123 WTO members would be needed if this went to a vote under Article IX of the WTO Agreement. Even optimistically, the current number of WTO members supporting the waiver is only half that total. In reality, when deciding on whether a consensus or majority approach will be sought, the Chair of the WTO General Council will have a great deal of discretion as to what will happen next. He will make that decision based on the information he receives from the Chair of the TRIPS Council, but there will be no vote taken at the TRIPS Council itself. Only the WTO Ministerial Conference (slated for November 30 – December 3 2021) can decide this. We do expect some sort of WTO Declaration on IP and COVID-19 to emerge by December 3, but whether this is anywhere close to current TRIPS waiver proposals remains to be seen. Watering down the current TRIPS waiver proposals to achieve a consensus or majority vote remains a very real possibility.

Meanwhile, the academic debate has crystallized around almost diametrically opposed pro-waiver and anti-waiver positions. Our view is that both positions have their merits and their drawbacks, but that, in reality, pro- and anti-waiver arguments are not binary.

Already, we have stressed this in our letter to the Financial Times , published on May 12, 2021, just days after the Biden Administration’s announcement of support for a waiver. We argue that debating IP waivers will fuel pandemic innovation (the original, unedited version of our letter is available here ).

In our longer Financial Times opinion of June 17, 2021, we then called for greater transparency of ownership, licensing, and advance purchase agreements to inform a better understanding of the effects of IP during the pandemic response (the original, unedited version of our opinion is available here ). As we state in the Financial Times , the COVID-19 response requires a toolkit of policies to ensure adequate vaccine manufacturing and delivery. The current focus on the role of IP can be part of that toolkit, and its interface with collaboration and knowledge transfer in responding to these challenges must be key components of that response.

Opinions differ on what long-term impact a potential IP waiver would have on pandemic responses and future innovation. There are also debates about whether it is the best tool to reach the necessary goals. Yet, it is understandable that the waiver is being considered as a possible approach for countries seeking to scale up manufacturing and supply and improve affordability.

However, regardless of whether a WTO waiver is ever achieved, it will not alone solve the access problem. More broadly, the debate about an IP waiver will focus attention on the ability for WTO members to apply pressure on the manufacturers of COVID-19 vaccines and related health care technologies. It will make clear that, while voluntary approaches are preferred, compulsory licenses, or even waiving IP remains the ultimate sanction if IP owners are not willing to transfer technology in order to scale up production, lower prices, and achieve more equitable distribution globally.

In many ways, the current focus on a TRIPS waiver is likely to create these pressure points, regardless of whether it realizes final agreement at the WTO Ministerial Conference. Attention is already focusing on rethinking manufacturing and improving supply chains, and this is likely to include: a greater willingness to engage in voluntarily licensing agreements, participation in technology access pools (C-TAP), greater transparency of Advance Purchase Agreements, greater transparency and sharing of regulatory data, mechanisms (including regulatory obligations and incentives) to increase transfer of tacit know-how, compulsory licensing, more inclusive and more comparable clinical trial designs , and greater recourse to competition law.

Ultimately, the world needs to find sustainable solutions to address not only the current crisis, but also to assist with future pandemic preparedness. These solutions may include, inter alia : (1) greater consideration of the role of regional manufacturing hubs, (e.g., the recent WHO announcement of support for the South African consortium to establish the first COVID mRNA vaccine technology transfer hub , which can assist with knowledge transfer to speed up manufacturing and supply), (2) collaboration between global organizations, such as the recent collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO), World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), and WTO, (3) a WHO Pandemic Preparedness Treaty , and (4) a joint EU-U.S. COVID Manufacturing and Supply Chain Taskforce .

We recognize that some of these initiatives may not come to fruition, or may not contribute substantively to improved manufacturing, supply, and affordability, but they are steps in the right direction.

These steps are being taken not least because the TRIPS waiver proposal has focused attention on the role of IP during the pandemic. For this, the TRIPS waiver debate must be commended. Without it, the current debate would lack substantive focus. Going forward, practical solutions should focus on scaling up manufacturing and supply, and improving access and affordability, while maintaining the long-term objectives of the innovation system and contributing to future pandemic preparedness.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Timo Minssen

Timo Minssen is Professor of Law at the University of Copenhagen (UCPH) and the Founder and Managing Director of UCPH's Center for Advanced Studies in Biomedical Innovation Law (CeBIL). He is also affiliated with Lund University as a researcher in Quantum Law. His research concentrates on Intellectual Property, Competition & Regulatory Law with a special focus on new technologies in the pharma, life science & biotech sectors including biologics and biosimilars. His studies comprise a plethora of legal issues emerging in the lifecycle of biotechnological and medical products and processes - from the regulation of research and incentives for innovation to technology transfer and commercialization.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Sign up for our newsletter

News & Insights

- North America

- Los Angeles

- Northern Virginia

- San Francisco

- Silicon Valley

- Washington, D.C.

- Europe & Middle East

- Capabilities

- Corporate, Finance and Investments

- Activist Defense

- Banking and Institutional Finance

- Capital Markets

- Construction and Procurement

- Corporate Governance

- Emerging Companies and Venture Capital

- Employee Benefits and Executive Compensation

- Energy and Infrastructure Projects

- Financial Restructuring

- Global Human Capital and Compliance

- Investment Funds and Asset Management

- Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A)

- Middle East and Islamic Finance and Investment

- Private Credit & Special Situations

- Private Equity

- Public Companies

- Real Estate

- Structured Finance and Securitization

- Technology Transactions

- Government Matters

- Data, Privacy and Security

- Environmental, Health and Safety

- FDA and Life Sciences

- Government Advocacy and Public Policy

- Government Contracts

- International Trade

- National Security and Corporate Espionage

- Securities Enforcement and Regulation

- Special Matters and Government Investigations

- Trial and Global Disputes

- Appellate, Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Bankruptcy and Insolvency Litigation

- Class Action Defense

- Commercial Litigation

- Construction and Engineering Disputes

- Corporate and Securities Litigation

- E-Discovery

- Intellectual Property

- International Arbitration and Litigation

- Labor and Employment

- Product Liability

- Professional Liability

- Toxic & Environmental Torts

- Industries / Issues

- Automotive, Transportation and Mobility

- Energy Transition

- Financial Services

- Food and Beverage

- Higher Education

- Life Sciences and Healthcare

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

- Buy American

- Crisis Management

- Doing Business in Latin America

- Environmental Agenda

- Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)

- Focus on Women's Health

- Russia/Ukraine

- Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs)

- Experienced Lawyers

- Law Students

- UK Graduate Recruitment

- Judicial Clerks

- Other Professionals

- News & Insights

- Cases & Deals

- In the News

- Press Releases

- Recognitions

- Conferences

- Speaking Engagements

- All Insights

- Newsletters

- Client Alerts

- Thought Leadership

- Auditor Liability Bulletin

- ESG Excellence

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Women’s Initiatives

- Racial Diversity

- LBGTQ+ Affinity

- Citizenship

- Community Focus

Client Alert

June 7, 2021

Update on the Proposed TRIPS Waiver at the WTO: Where is it Headed, and What to Expect?

On June 8-9, 2021, the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) TRIPS Council will hold their first meeting in the wake of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announcing “the Biden-Harris Administration’s support for waiving intellectual property protections for COVID-19 vaccines” under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement). A TRIPS waiver, if issued, could potentially permit the unimpeded manufacture and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, diagnostic kits, and therapeutics without regard for the intellectual property rights of the inventors and developers of the technologies that enabled their development, and without following existing effective processes for ensuring widespread access to life-saving immunizations, testing, and treatment.

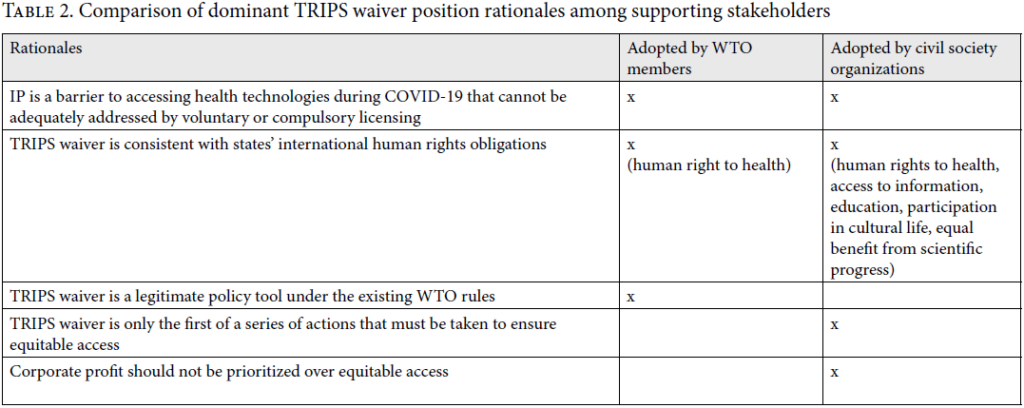

Since the USTR’s announcement, 62 countries sponsoring a TRIPS waiver issued a revised proposal 1 Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, TRIPS Communication IP/C/W/669/Rev.1 (May 21, 2021) to advance text-based negotiations; China expressed openness to discussing the waiver; Germany and others stated their continued opposition, and the EU has urged a “third way” proposal. The TRIPS waiver has also been disputed in U.S. Congress, with some opponents introducing legislation to limit USTR’s authority to agree to a waiver in the WTO. The public debate over the waiver has shifted as well – with an increasing focus on trade secrets, technology transfer, supply chain constraints, and other factors impacting global vaccine production aside from any effects of patent rights.

Continue reading for our update on where the TRIPS waiver proposal is headed; the practical concerns raised by the proposal; and potential legal limitations that may impact passage and implementation of a TRIPS waiver. And see our previous client alert on the TRIPS waiver proposal for additional background and insights.

Where does the TRIPS waiver stand, and where is it headed?

In their original October 2, 2020 submission to WTO, India and South Africa proposed waiving member countries’ TRIPS obligations to protect any patents, copyrights, industrial designs, or trade secrets (“undisclosed information”) “in relation to prevention, containment or treatment of COVID-19,” until “widespread vaccination is in place globally.” 2 Waiver from Certain Provisions of the TRIPS Agreement for the Prevention, Containment and Treatment of COVID-19, TRIPS Communication IP/C/W/669 (Oct. 2, 2020)

For months thereafter, the waiver proposal remained deadlocked in the WTO, largely with developing nations signing on to sponsor or support the waiver, and multiple developed nations opposing the waiver in favor of alternative approaches to increasing global vaccine equity. But on May 5, 2021, USTR Katherine Tai made the unprecedented announcement that the Biden-Harris Administration “supports the waiver of [intellectual property] protections for COVID-19 vaccines,” and “will actively participate in text-based negotiations at the [WTO] needed to make that happen.” 3 See Statement from Ambassador Katherine Tai on the COVID-19 TRIPS Waiver (May 5, 2021), available at https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2021/may/statement-ambassador-katherine-tai-covid-19-trips-waiver

Since then, international positions surrounding the waiver proposal have been evolving at a rapid pace – with new developments reported almost daily. China announced on May 18 that it would support a TRIPS waiver “that is conducive to fair access to vaccines in developing countries” 4 See Inside Health Policy, Tai Talks TRIPS Waiver with Allies as China Gets Behind it, GOP Balks (May 20, 2021), available at https://insidehealthpolicy.com/daily-news/tai-talks-trips-waiver-allies-china-gets-behind-it-gop-balks ; Germany expressly stated opposition to a TRIPS waiver; and the EU more broadly announced support for a “third way” alternative that includes “trade facilitation and disciplines on export restrictions,” “support for the expansion of production” (including through voluntary licensing agreements), and “clarifying and simplifying the use of compulsory licenses [under TRIPS] during crisis times.” 5 See Health Policy Watch, G20 Leaders Promise to Share More Vaccines While EU Digs in Against TRIPS Waiver (May 21, 2021), available at https://healthpolicy-watch.news/g20-leaders-promise-to-share-more-vaccines-while-eu-digs-in-against-trips-waiver/; European Commission, Opening Statement by Executive Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis at the European Parliament plenary debate on the Global COVID-19 challenge (May 19, 2021), available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019-2024/dombrovskis/announcements/opening-statement-executive-vice-president-valdis-dombrovskis-european-parliament-plenary-debate_en; Bloomberg, EU’s Trade Response to Pandemic Stops Short of Vaccine IP Waiver, available at https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-03/eu-s-trade-response-to-pandemic-stops-short-of-vaccine-ip-waiver WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, who has supported a “third way” in recent months, 6 See Statement of Director-General Elect Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala to the Special Session of the WTO General Council (Feb. 13, 2021), available at https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news21_e/dgno_15feb21_e.pdf now states that “we must act now to get all our ambassadors to the table to negotiate a [waiver] text.” 7 See supra note 5

Notably, the USTR’s support for a waiver targeting “COVID-19 vaccines ” differs substantially from the May 21, 2021 revised proposal by India, South Africa and their 60 co-sponsors – which relates broadly to “ health products and technologies … for the prevention, containment or treatment of COVID-19.” Under the sponsors’ revised proposal, WTO members would be relieved (for at least 3 years) of their TRIPS obligations to protect patents, copyrights, industrial designs and trade secrets for any “ diagnostics, therapeutics, vaccines, medical devices, personal protective equipment ” used in relation to preventing, containing or treating COVID-19 – as well as “ their materials or components, and their methods and means of manufacture .” Notably, the revised proposal is not substantially different from the original proposal, and suggests that WTO members may remain divided on this controversial issue.

The next meeting of the TRIPS Council to discuss the waiver proposal is taking place on June 8-9, 2021, and will be closely watched. Because any TRIPS waiver would require consensus of all 164 WTO member countries, any text-based negotiations that take place would likely proceed over the course of several months or more.

Proponents have advanced the proposed TRIPS waiver in the name of meeting global vaccine demand. But even in the absence of a waiver, pharmaceutical manufacturers have continued efforts to expand global production and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and therapies, with a focus on expanding access to developing countries. For example, Pfizer announced its plan to deliver two billion doses to developing nations over the next 18 months, with one billion doses coming this year. 8 Wall Street Journal, Pfizer, BioNTech to Deliver 2 Billion Covid-19 Vaccine Doses to Developing Countries (May 21, 2021), available at https://www.wsj.com/livecoverage/covid-2021-05-21/card/GsPYoFscRppTzYYt0l4f One forecast estimates that, by the end of 2021, total global COVID-19 vaccine production may exceed 11 billion doses – an amount potentially sufficient to achieve global herd immunity. 9 Airfinity, How Much Vaccine Will be Produced This Year? (May 19, 2021), available at https://www.airfinity.com/insights/how-much-vaccine-will-be-produced-this-year

Several pharmaceutical industry groups have also proposed a five-step plan to “urgently advance COVID-19 equity,” including: (1) increasing dose sharing among countries through COVAX and other mechanisms; (2) optimizing production of vaccines and raw materials; (3) eliminating trade barriers for critical raw materials; (4) supporting country readiness to deploy vaccination programs; and (5) driving further innovation. 10 IFPMA, Five steps to urgently advance COVID-19 vaccine equity (May 19, 2021), available at https://www.ifpma.org/resource-centre/five-steps-to-urgently-advance-covid-19-vaccine-equity/

Manufacturers have also continued to partner with other companies in efforts to scale up global production. For example, Moderna recently engaged Samsung Biologics to provide fill-and-finish manufacturing for Moderna’s vaccine. 11 Samsung Biologics, Moderna and Samsung Biologics Announce Agreement for Fill-Finish Manufacturing of Moderna's COVID-19 Vaccine (May 22, 2021), available at https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/moderna-and-samsung-biologics-announce-agreement-for-fill-finish-manufacturing-of-modernas-covid-19-vaccine-301297280.html Merck and Gilead also each entered into or expanded voluntarily licensing programs with manufacturers in India to produce the companies’ respective COVID-19 antiviral agents molnupiravir and remdesivir. 12 Fierce Pharma, Gilead, Merck step in to help India's drug manufacturers fight surging COVID-19 outbreak (Apr. 27, 2021), available at https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/gilead-merck-plan-production-boosts-for-covid-19-drugs-india-amid-surging-outbreak

Some WTO members have also considered using the existing TRIPS flexibilities to expand their vaccine access. For example, Bolivia has continued to pursue its effort to import the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine from Canadian company Biolyse Pharma, under a compulsory license pursuant to TRIPS Article 31 bis (if one could be obtained). 13 WTO News, Bolivia outlines vaccine import needs in use of WTO flexibilities to tackle pandemic (May 12, 2021), available at https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news21_e/dgno_10may21_e.htm

How might a TRIPS waiver impact ongoing efforts to scale COVID-19 vaccine production?

A TRIPS waiver would potentially hurt, not help, the current efforts to expand global production of COVID-19 vaccines and therapies. For example, expanding vaccine production to unlicensed manufacturers could further exacerbate the challenging supply chain issues and high demand for limited raw materials that have hindered even the authorized vaccine manufacturers from scaling up production in recent months. 14 See, e.g. , EndPoints News, As fears mount over J&J and AstraZeneca, Novavax enters a shaky spotlight (Apr. 21, 2021), available at https://endpts.com/as-fears-mount-over-jj-and-astrazeneca-novavax-enters-a-shaky-spotlight/; New York Times, U.S. to Send Virus-Ravaged India Materials for Vaccines (Apr. 25, 2021), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/25/us/politics/india-us-coronavirus.html

A TRIPS waiver could also disincentivize the current vaccine manufacturers from entering into further voluntary licensing agreements with manufacturing partners in other countries. In the wake of the USTR’s announcement, supporters of a TRIPS waiver have shifted the public discussion from patents to confidential trade secrets and technology transfer – acknowledging that waiving patent rights would not be sufficient to expand global production of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines. 15 Financial Times, Biden Urged to Oblige US Vaccine Makers to Share Technology (May 15, 2021), available at https://www.ft.com/content/9408223f-0a6c-43b7-9f67-c7e4697005c2 But, in the absence of voluntary licensing agreements, there is no clear mechanism for countries to compel the original vaccine manufacturers to divulge trade secrets or provide technology transfer support to unlicensed parties. And if pharmaceutical companies perceive that their technology transfer to a voluntary licensee could lead to the licensee’s country disseminating their competitively sensitive know-how, they might forgo such voluntary licensing entirely.

Likewise, global pharmaceutical development could be seriously harmed if WTO members use a TRIPS waiver to divulge the vaccine manufacturers’ confidential trade secrets submitted during regulatory review – information that TRIPS generally protects from disclosure and unfair commercial use by unauthorized parties. 16 See TRIPS Agreement, Article 39.3 If pharmaceutical companies perceive that submitting to regulatory review in certain countries means losing protections for proprietary manufacturing processes and other competitively sensitive trade secret information, those companies might consider avoiding such countries altogether when considering where to develop, make, sell, or license their products.

Finally, the TRIPS waiver could negatively impact the continued development of COVID-19 vaccine. There are more than 60 additional vaccines under development worldwide; and for many of these efforts, the investment of time and money is premised on the potential for licensing the vaccine or partnering with a larger manufacturer to produce it. Prospectively waiving intellectual property protections for these vaccines in development will likely undermine continued investment and research – a proposition made all the more alarming due to the possibility of new and different strains of COVID-19.

What legal factors might prevent passage or limit implementation of a TRIPS waiver?

The most immediate hurdle to passage of a TRIPS waiver lies in the requirement that all 164 WTO member countries agree to a specific waiver text. As noted above, Germany (among others) presently objects to any waiver proposal; the U.S. has only stated support for a waiver of significantly narrower scope than the sponsors’ current proposal; and a “third way” proposal that sidesteps a TRIPS waiver remains on the table. And in the U.S., legislation has been proposed in Congress to limit the USTR’s authority to agree to a TRIPS waiver, e.g. , by requiring Congressional approval of any waiver, 17 See, e.g. , H.R. 3236, 117th Cong. or prohibiting the use of federal funds to support a waiver. 18 See, e.g. , H.R. 3035, 117th Cong.; S. 1683, 117th Cong. One of the proposals in the Senate was narrowly voted down, but garnered some bipartisan support. We expect that Congressional interest will remain high on this topic, and there may be a pathway to bipartisan action that would constrain the Administration’s waiver of IP protections under TRIPS.

Even if a TRIPS waiver of some scope were passed in the WTO after text-based negotiations, hurdles would remain to its effective implementation. A TRIPS waiver would not change the applicable IP protections in the WTO member states; and each member state would need to decide on their own (through their individual lawmaking procedures) whether and how to change their domestic laws within the scope permitted by the TRIPS waiver. It is unlikely that the resulting global patchwork of inconsistent IP protections would facilitate further expansion of vaccine production – particularly if voluntary technology transfer from existing manufacturers remains critical to making safe and effective vaccines at scale.

To that end, some waiver proponents have called on the U.S. to compel technology transfer from the U.S.-based vaccine manufacturers. 19 See supra note 15 But current U.S. statutes largely prohibit the FDA and other regulatory agencies from publicly divulging trade secret information submitted for purposes of regulatory approval. 20 See, e.g. , 21 U.S.C. § 331(j); 18 U.S.C. § 1905; 5 U.S.C. § 552(b)(4); Chrysler Corp. v. Brown , 441 U.S. 281 (1979) And even if authorized by future legislation, the Taking Clause of the Fifth Amendment would likely prohibit the U.S. government from disclosing trade secret information submitted under the current statutory and regulatory protections, without just compensation ( e.g. , damages awarded against the U.S. under the Tucker Act by the Court of Federal Claims). 21 See, e.g. , Ruckelhaus v. Monsanto Co. , 467 U.S. 986 (1984); 28 U.S.C. § 1491

Additionally, even in the wake of a TRIPS waiver, companies subject to unauthorized use of their COVID-19 vaccine or therapy IP outside the U.S. may have remedies available under international law. Even though the type of obligations included in TRIPS are also included in certain U.S. trade agreements, such as the United States-Canada-Mexico Agreement (the “USMCA”), it is highly unlikely that the current U.S. administration will seek to invoke state-to-state dispute settlement on this matter given their support of the waiver proposal. 22 See USMCA Ch. 20. Morever, in the event of a TRIPS waiver, the USMCA provides that “the Parties shall immediately consult in order to adapt this [agreement] as appropriate.” USMCA Art. 20.6(c)

IP rights holders can also consider the availability of investor-state dispute settlement or other arbitration procedures. For example, affected holders of IP rights might be able to bring claims for compensation against WTO member states under any applicable bilateral investment treaties (BITs) – to the extent that such treaties do not contain express exceptions to IP‑related rights under the TRIPS Agreement. Foreign investors may be able to claim that such states had committed to providing greater protections under any applicable BIT, such that these protections cannot be displaced by any waiver under the TRIPS Agreement. That said, such states – particularly those with limited resources – may try to rebut any claims of wrongfulness by asserting an ongoing state of necessity for public health emergencies during the COVID‑19 global pandemic. The strength of a potential claim under a BIT would be fact-specific for each IP rights holder, and should be assessed individually.

* * *

In light of continuing developments at the WTO, companies that hold intellectual property in medical products related to COVID-19 should seek the advice of counsel to develop legal and policy strategies regarding the TRIPS waiver request, including (1) if they receive requests for licensing authorization, (2) if they learn of unauthorized use of their intellectual property, or (3) if they engage with national governments or international organizations to advocate for desired policy outcomes.

Featured Lawyers

Jamieson L. Greer Washington, D.C.

Jeffrey M. Telep (Jeff) Washington, D.C.

Daniel Crosby Geneva

Brian A. White Atlanta

Related Documents

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

WTO TRIPS Waiver for COVID-19 Vaccines

Sharing the know-how behind making COVID-19 vaccines is key to scaling up production and addressing emerging variants.

A Q&A WITH ANTHONY D. SO, MD, MPA

The Biden administration announced it would seek a “TRIPS waiver” of intellectual property protections related to COVID vaccines.

In this Q&A, Anthony D. So, MD, MPA , a professor of the practice in International Health , explains the waiver and what it could mean for COVID-19 vaccines.

What’s the TRIPS waiver for COVID vaccines all about?

The TRIPS waiver refers to a proposal, advanced by the governments of South Africa and India, to the World Trade Organization to waive intellectual property rights protection for technologies needed to prevent, contain, or treat COVID-19 “until widespread vaccination is in place globally, and the majority of the world’s population has developed immunity.”

In 1995, when the World Trade Organization came into existence, those signing up as members agreed that in exchange for the lowering of barriers to trade, they would abide by the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, or TRIPS.

This Agreement, pushed by knowledge-based economies like the United States and the multinational, research-intensive pharmaceutical industry, imposed a base of protections for intellectual property rights, from patents to copyrights. Before this was negotiated, more than 50 countries did not recognize patent protection on pharmaceutical products. The TRIPS Agreement changed that, and after a transition period of 10 years, ratcheted up these requirements on all but the least developed countries.

Middle-income countries like India came into compliance by 2005. The TRIPS waiver just seeks to temporarily suspend these protections until the pandemic has ended, so the world can better access the knowledge needed to combat the worst pandemic in a century.

What’s the rationale behind waiving intellectual property protections for COVID vaccines?

Sharing the know-how behind making COVID-19 vaccines is key to not only scaling up production, but also bringing forward the second generation of vaccines we will need to address emerging variants.

No single vaccine manufacturer can produce enough vaccines to cover the globe, and demand has far outstripped supply, with high-income countries taking the lion’s share of reserved doses. Proponents of a TRIPS waiver wonder how it can be right for a multinational vaccine manufacturer to hold exclusive rights that can stop other firms from stepping up to meet the need for vaccines, particularly in markets not being served by current vaccine producers. They argue that the public already has paid once or twice for such innovation, either upfront in research and development (R&D) costs or through purchase guarantees of these products, or both.

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine—one of two now in use based on an mRNA platform—was paid for largely by the U.S. government, and in fact, Moderna has pledged not to enforce its patents related to the COVID-19 vaccine during the pandemic. However, making the Moderna vaccine likely involves other companies’ patented equipment and processes as well, so waiving patent protections on one piece of the process may not help other companies make the entire “recipe.”

This is why a TRIPS waiver is considered important to ensure other vaccine manufacturers would have the freedom to operate. It should also be acknowledged that a TRIPS waiver may accelerate scaling up some COVID-19 vaccines where untapped capacity for vaccine production still exists, and it may also encourage existing vaccine producers to step up their technology transfer efforts.

By noting its willingness to move forward with text-based negotiations over a TRIPS waiver at the World Trade Organization, the United States signaled a seismic shift in policy. However, it is only the beginning of a process.

Who is opposing the TRIPS waiver and why?

Other high-income countries, from EU countries and the United Kingdom to Japan and Australia, have yet to join the United States in supporting negotiations for a TRIPS waiver. Multinational pharmaceutical companies have vocally opposed the waiver, and disclosure forms from the first quarter of 2021 reveal that over 100 lobbyists had been enlisted to oppose the TRIPS waiver.

The main arguments boil down to protecting the incentive for future pharmaceutical innovation. The idea is that companies will be reluctant to invest in new technology if they feel that they cannot reap full financial benefit from their successes.

Yet before COVID-19 hit, R&D for pandemic vaccines was largely neglected by the private sector, and public financing understandably had to support this work. Many of the first COVID-19 vaccines that came to market relied on tax dollars to enable their effective development.

One of the key aspects of producing successful COVID-19 vaccines has been the process of stabilizing the COVID-19 spike protein. This innovation relied largely on public funding, and all of the vaccines currently on the U.S. market rely on this technology. But although they all benefited from publicly funded intellectual property, no vaccine company has stepped forward to join a global effort to voluntarily share its know-how through the COVID-19 Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), launched by WHO with the support of Costa Rica and 40 member state cosponsors.

Another question raised by opponents of the waiver is: Have companies been able to make a strong return on their investment? The answer appears to be yes. In a market almost entirely created by public sector purchase of vaccines for a pandemic, Pfizer brought in $3.5 billion in COVID-19 vaccine revenues in the first quarter of this year, with estimated profit margins in the high 20% range, by far its greatest revenue generator. Pfizer’s partner, BioNTech, received upfront public financing, both from the German government and the European Investment Bank, while Pfizer itself has secured 6 billion dollars thus far from the U.S. government in guaranteed purchases of its COVID-19 vaccine. So even if the TRIPS waiver were to enable other vaccine producers to meet the huge unmet demand, it is hard to argue that the public sector has not already provided multibillion-dollar incentives to bring forward needed innovation.

The pharmaceutical industry has also argued that the TRIPS waiver will not speed the scale-up of COVID-19 vaccines. This argument reflects the fact that the production process is very complex and difficult to develop without extensive support from existing manufacturers.

This may be particularly true for mRNA technology. While mRNA vaccine candidates are emerging in India and China as well, the intellectual property landscape for mRNA vaccines is highly fragmented, with a handful of pharmaceutical companies holding half of these patent applications. The TRIPS waiver would clear the path for these firms to move forward, as they enter clinical testing, without concern over conflicting patent claims that may not be resolved at pandemic speed.

Unlike Pfizer and Moderna, which make mRNA vaccines, AstraZeneca/Oxford has struck many more technology transfer agreements with vaccine producers in low- and middle-income countries for its vaccine based on adenovirus vector technology, which is easier to produce and distribute. Its vaccine price of $3 per dose is also less than half that of Pfizer/BioNTech’s vaccine in the African Union.

With first-generation vaccine producers already focused on booster doses to take on variants affecting high-income countries, will they be as focused when a variant spreads through lower-income country markets that largely remain unvaccinated? Two-thirds of the WTO’s members support the TRIPS waiver because they are unsure that their COVID-19 public health needs will be met by upholding patent protections as usual. Perhaps this reflects the experience of these countries’ governments in securing access to Pfizer/BioNTech vaccines, let alone the building blocks of knowledge to develop second-generation vaccines. Pfizer has been asking governments to put sovereign assets—such as federal bank reserves, embassy buildings, or military bases—as a guarantee against indemnifying the cost of future legal cases.

What else, beyond resolving intellectual property issues, is necessary to scale up vaccine production?

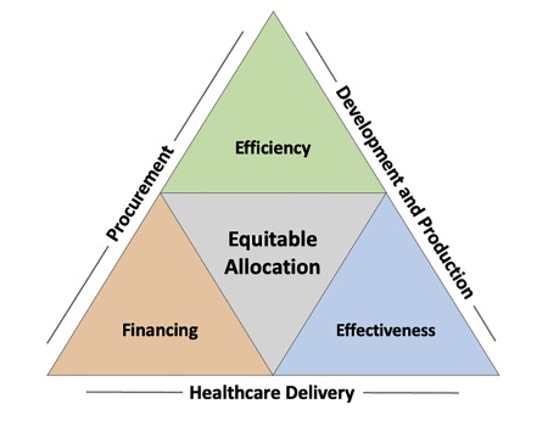

These negotiations over a TRIPS waiver will not take place overnight, nor will scaling up the technology transfer and ramping up the manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines. In a perspective piece for Cell’s new translational science journal, we recently discussed the complex issues involved in scaling up vaccine production and, importantly, ensuring that these vaccines make their way not only to high-income countries, but also more equitably to those in need across the globe. This will involve, among other things:

- Public investment in technology transfer

- Contracting of existing and new manufacturing facilities

- Sourcing other inputs like glass vials

- Pooled procurement facilities, from UNICEF to the Pan American Health Organization’s Revolving Fund for Vaccine Access, to buy and deliver the vaccines effectively.

We will also need to prioritize scaling up second-generation vaccines that have been adapted to address emerging variants or that are better suited for delivery where ultra-cold chains do not exist.

Source: So AD, Woo J. Achieving path-dependent equity for global COVID-19 vaccine allocation. Med 2021; 2(4): P373-377. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medj.2021.03.004

What are the next steps?

For years to come, we will need COVID-19 vaccines. A sustainable and affordable pipeline—one that will deliver in a timely way to all in need, not just to those in wealthy countries—must be put in place.

In the best-case scenario, a TRIPS waiver for sharing COVID-19-related knowledge and technology can lay an important foundation to an innovation ecosystem that ensures a fairer path out of the pandemic than we took going into the pandemic.

But no one doubts that there is a tough road ahead in negotiating the text to this waiver and in all the work that follows so that it might make an effective difference. Other questions will naturally arise, including the approach to intellectual property for tests and treatments for COVID-19, as well as the sharing of key research findings and data.

In the near term, the U.S. should also commit to sharing-and-exchange mechanisms for COVID-19 vaccines, especially as uptake of vaccines slows.

We had proposed a temporal trade, for example, on the U.S.-reserved doses of the not-yet-approved AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine with countries waiting and ready to use this vaccine now. By just swapping our line in the queue, vaccine doses may reach those in desperate need sooner. More such arrangements will be needed, particularly since AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine supplies globally have since been disrupted with the unfolding COVID-19 resurgence in India, from where much of its manufacture had been sourced.

In the meantime, the world must not lose any time in scaling up the public sector investment in the rest of the supply chain, from manufacturing to logistical delivery of these vaccines. The U.S. can lead a coalition of the willing to build upon and extend the use of such vaccine platforms through technology transfer. History will remember what is done to meet this moment.

Anthony So, MD, MPA , is a professor of the practice in International Health and the founding director of the Innovation+Design Enabling Access (IDEA) Initiative .

RELATED CONTENT

- The New Technology Behind COVID-19 RNA Vaccines and What This Means for Future Outbreaks

- Can COVID-19 Vaccines Be Mandatory in the U.S. and Who Decides?

- Enhancing Public Trust and Health with COVID-19 Vaccination

Related Content

Outbreak Preparedness for All

What’s Happening With Dairy Cows and Bird Flu

New Grant Enables Johns Hopkins Researchers to Implement Community Health Worker-Led Health Interventions for Noncommunicable Diseases in Nepal

How Dangerous is Dengue?

New Johns Hopkins Institute Aims to Safeguard Human Health on a Rapidly Changing Planet

The June 17, 2022 WTO Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement

Updated Friday, 17 June 2022, 11:30 AM Geneva time.

Early Friday morning, 17 June 2022, the WTO’s 12th Ministerial Conference (chaired by Timur Suleymenov, Kazakshstan), adopted a Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement (WT/MIN(22)/W/15/Rev.2). The text can be found here .

There were several changes since the June 10 version. The agreement is a limited and disappointing outcome overall that is most accurately described as a narrow and temporary exception to an export restriction, not a waiver.

The Clarifications

There are several so called clarifications in the text on topics, which restate the existing flexibility in TRIPS, sometimes at the risk here of making the provisions seem exceptional, although some developing countries have welcomed them. Among the clarifications, none of which add new legal benefits, are paragraphs 2, 3(a) and 4 of the agreement. The Clarification offered on Article 39.3 of the TRIPS is somewhat helpful, but essentially restates the existing safeguard already part of 39.3. The clarification on paragraph 3(d) and footnote 4 on remuneration do not change TRIPS standards, but will be helpful in national settings, including by the fact that the WTO Ministerial Decision is citing “the Remuneration Guidelines for Non-Voluntary Use of a Patent on Medical Technologies published by the WHO (WHO/TCM/2005.1).” (I am the author of that document).

The TRIPS restriction on exports under Article 31

The TRIPS agreement contains 73 Articles describing various obligations on WTO members as regards the granting and enforcement of intellectual property rights.The original waiver proposal would have provided a clean waiver of 40 Articles in the TRIPS, as regards the manufacturing and supply of any COVID 19 countermeasure. The new considerably scaled back agreement focuses on just one part of the agreement, the 20 word paragraph 31.f which limits exports made under a non-voluntary authorization, often referred to as a compulsory license. The text reads.

(f) any such use shall be authorized predominantly for the supply of the domestic market of the Member authorizing such use;

Article 31.f of the TRIPS is controversial, and often considered an embarrassment to the WTO, because it is designed to limit the economies of scale for products manufactured under a compulsory license, and it also has a very differential impact on countries depending upon their size. For big economies like the U.S., China, India or to some extent Brazil, the impact is less severe than would be for a country like Chile, Ecuador, Portugal, New Zealand, or Thailand, but for every country, it is an odd provision for an organization created to liberalize trade and exploit comparative advantages.

The original TRIPS agreement contains several important workarounds from the 31.f restrictions on exports. Most obviously, Article 31.k of TRIPS waives 31.f, when a compulsory license is a remedy to an anti-competitive practice, which can include, among other grounds, a finding that prices are excessive, or that a patent holder refuses to license a technology on reasonable terms, or that the patented invention is an essential facility, all highly relevant grounds for a vaccine compulsory license.

There is also the possibility to export under Article 30 of the TRIPS, if an exception passes a three step test. The Article 30 approach was strongly supported by health NGOs, generic manufacturers, the World Health Organization (WHO), and several countries in the 2002.2003 negotiations over this issue, and even tested in a 2000 WTO TRIPS dispute case ( DS114 ) relating to the early working of patented inventions, but opposed by the European Union, which favored what is now Article 31bis of the TRIPS.

Arguably the best way to address the export issue is found in the enforcement section of the TRIPS. Under Article 44 of TRIPS, a government or a judicial authority can limit the remedies to infringement to the payment of royalties, including cases where 100 percent of manufacturing output is exported.

In terms of state practice, the Articles 31.k and 44 approaches are the most widely used, by far. (More on the export alternatives here .)

Article 31bis

Article 31bis of the TRIPS was initially adopted by the WTO General Council on August 30, 2003, as an optional waiver of Article 31.f. The core elements of 31 bis are notifications to the WTO, anti-diversion measures, restrictions on eligibility and scope.

31bis applies to drugs, vaccines and some diagnostic tests. It is permanent. It applies to all diseases. 31bis limits the members that can benefit as importers.

In the 19 years since its adoption, the 31bis mechanism has been successfully used only once, by Apotex in Canada for an export of an HIV drug to Rwanda, working with MSF. Apotex indicated it would never attempt to use the mechanism again, giving the complexity and delays they experienced. The Article 31bis mechanism is implemented through national laws, and much of the problems Apotex faced were due to Canadian law and the Canadian government administration of the statute. Few countries have bothered to implement Article 31bis in national statutes, but among those that have, the statutes in India and China offer far more streamlined approaches. India’s version is Section 92a of the patents act, titled “Compulsory licence for export of patented pharmaceutical products in certain exceptional circumstances.” The first two paragraphs in Section 92A of the India patents act read as follows:

(1) Compulsory licence shall be available for manufacture and export of patented pharmaceutical products to any country having insufficient or no manufacturing capacity in the pharmaceutical sector for the concerned product to address public health problems, provided compulsory licence has been granted by such country or such country has, by notification or otherwise, allowed importation of the patented pharmaceutical products from India. (2) The Controller shall, on receipt of an application in the prescribed manner, grant a compulsory licence solely for manufacture and export of the concerned pharmaceutical product to such country under such terms and conditions as may be specified and published by him.

To date, the India statute has not been tested, but pending compulsory licenses for COVID therapeutics in Latin America may provide timely tests, if any of the cases succeed in the Latin American county.

It is important to note that Article 31bis of the TRIPS is very long, including an Article 31bis, an “Annex to the TRIPS” and and “Appendix to the Annex to the TRIPS Agreement.” The WTO analytical index for 31bis is more than five pages single spaced.

Article 31bis notifications

The Article 31bis notifications requirements are seen as a significant problem, in part because governments have to make notifications to the WTO before the exports take place, and also that the notifications involve quantities, even in cases where the importing country is not certainly how many units to purchase, or when the government is not the sole market for the product.

Governments around the world often see the use of compulsory licensing of patented inventions as politically sensitive, inviting considerable pressure from the United States, the European Union and several of its members and Switzerland. WTO notifications on the prior use of a compulsory license will typically involve several ministers or agency heads, including those working on trade, foreign affairs, health and intellectual property rights, if not heads of state. 31bis requires such notifications from both importing and exporting countries. By, as a practical matter, involving trade and foreign affairs officials, there is a greater opportunity for bilateral pressures to block actions. KEI has worked on multiple cases where importing countries were not willing to make a notification as potential importers without having a committed supplier, and the suppliers could not get their governments to make a notification regarding exporting, without the importing country having made its notifications. All of this has to be repeated for each authorization, which includes specifications of qualities and designations. These were the Rwanda and Bolivia notifications as importers, the only two received by the WTO in 19 years. ( Bolivia , Rwanda ), and Canada as an exporter, the one time an export was actually approved under the 31bis mechanism. ( Canada )

Article 31bis anti-diversion obligations Article 31bis does contain several sections regarding the obligations on importing and exporting countries to prevent the re-exportation of the products. Governments are not sure how burdensome the obligations are in practice, but they do go beyond the obligations included in the pre-31bis TRIPS text, and seem to be conflict with Articles 6 of the TRIPS on the exhaustion of rights. They may also increase the costs to the supplier if they cannot re-export unused products when the forecast demand is not met in one country.

The new Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement

The new Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement provides an exception to 31.f export restrictions that is temporary, applies only to vaccines and only to COVID 19, limits which countries and import or export, and contains notification and anti-diversion oblations.

Eligibility for importers and exporters

As noted, Article 31bis provides no limits on which countries can use the exception as exporters, but does limit the eligible importing countries. The 31bis limits on importing eligibility is implemented through an opt-out process, and countries were allowed to opt out as importers in general (37 members have done so, see open letter of April 7, 2020 ), or to declare they would only use the mechanism in emergencies.

The new Ministerial Decision on TRIPS defines eligibility for both importing and exporting in footnote 1:

For the purpose of this Decision, all developing country Members are eligible Members. Developing country Members with existing capacity to manufacture COVID-19 vaccines are encouraged to make a binding commitment not to avail themselves of this Decision. Such binding commitments include statements made by eligible Members to the General Council, such as those made at the General Council meeting on 10 May 2022, and will be recorded by the Council for TRIPS and will be compiled and published publicly on the WTO website.

While the opt-out language on eligibility is similar to the approach taken in the August 30, 2003 waiver of Article 31.f of the TRIPS, which is now part of TRIPS as 31 bis , there is an important difference. The new agreement limits the countries eligible to import or export.

There is an expectation that all non-developing countries with the current ability to manufacture and export vaccines will opt out. The status of China seems to be addressed in the reference to the May 10 meeting of the General Council, where China expressed willingness to opt out. This is in some ways an astonishing result. The WTO will continue to enforce export restrictions on vaccines from most of the leading vaccine manufacturing countries including many with sophisticated technology. At an NGO briefing during the negotiations, WTO DG Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala seemed to justify this outcome on the grounds that it would be desirable protectionism to achieve the objective of promoting vaccine manufacturing capacity in Africa and other developing countries.

Notifications

The new Decision had marginally less problematic notifications, the most notable improvement is that notifications can be made “as soon as possible after the information is available,” and while it is not exactly clear how different the requirement is, it does seem like an improvement from 31bis.

Anti-diversion

On the anti-diversion language, the new Decision has one notable but perhaps narrow improvement over 31bis, stating that “in exceptional circumstances, an eligible Member may re-export COVID-19 vaccines to another eligible Member for humanitarian and not-for-profit purposes, as long as the eligible Member communicates in accordance with paragraph 5.” NGOs such as TWN have pointed of that the Ministerial Decisions begins by “Noting the exceptional circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic,” so hard to say how to interpret the “in exceptional circumstances” language here.

The time period is 5 years, which severely limits its usefulness. Paragraph 5 states:

An eligible Member may apply the provisions of this Decision until 5 years from the date of this Decision. The General Council may extend such a period taking into consideration the exceptional circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic. The General Council will review annually the operation of this Decision.

The exception to the export restrictions will only last 5 years. There are currently no developing country vaccines manufactured under a compulsory license. Moderna is operating under a compulsory license from the United States, but the US will not be an eligible exporter. For the Ministerial Decision to have any use for vaccines, a developing country would have to issue a compulsory license on a vaccine or vaccine input, obtain regulatory approval for that vaccine, and export more than 50 percent of output. Under optimistic scenarios, it could take 2 to 3 years to bring a new COVID vaccine into the market, given the increasing challenges in obtaining regulatory approval not that emergency use authorizations have already been used for multiple vaccines. And that would only give the developer, if they began work today, a few years of sales under the exception. For this reason alone, the Indian government has predicted the Ministerial Decision would not lead to any new vaccine manufacturing. ( June 14, 2022, Statement by Shri Piyush Goyal during the WTO 12th Ministerial Conference at the meeting with co-sponsors of TRIPS Waiver )

“Second, with great difficulty we got the period of 5 years. But, we all know that by the time we get an investor, get funds raised, draw plans, get equipment and set up a plant, it will probably take 2.5-3 years to do that. After that, you will start producing and within 2 years, you will have to bring down your exports to the normal compulsory license level and your capacity will remain idle.”

The Ministerial Decision text will be tied with 31 bis as one of the worst ways to allow exports under a compulsory license. Articles 31.k, 30 and 40 all will dominate. (More on the alternatives here ).

The big pharma industry can be pleased with the precedents on notifications and anti-diversion, which are important to them, as well as the exclusion of most vaccine manufacturers and the 5 year duration.

It is hard to imagine anything with fewer benefits than this, as a response to a global health emergency (other than the earlier negotiating texts for this Decision). The fact that the exception is limited to vaccines, has a five year duration and does not address WTO rules on trade secrets makes it particularly unlikely to provide expanded access to COVID 19 countermeasures.

The pressure this week was to reach consensus in order to make multilateralism look like it works, which seems to have been the main justification for producing this decision.

Silver linings While the text is not expected to impact COVID 19 vaccine equity much or at all, there are some silver linings.

1. In terms of precedents going forward, the texts of notifications and anti-diversion are both much shorter and more usable than 31bis. 2. There is no 31bis requirement to limit imports to countries with no or insufficient manufacturing capacity, a sometimes ambiguous standard oddly unconnected to economic feasibility. 3. The fact that the Decision cites “the Remuneration Guidelines for Non-Voluntary Use of a Patent on Medical Technologies published by the WHO (WHO/TCM/2005.1)” will be useful in national settings. 4. If the decision is extended to therapeutics in six months, it may be much more value, given the supply constraints on therapeutics and the much better regulatory pathway. For therapeutics, even the language on 39.3 will be useful for some countries. 5. It’s not a TRIPS waiver, it’s a useful edit of some problematic elements of 31bis. But it also turns attention back to national governments to do things, and not wait on the WTO.

James Love Twitter: @jamie_love

- Access to Knowledge

- Access to Medicine

- Competition

- Government Funded research

- Intellectual Property Rights

- Legislation

- Negotiations

- Nuclear Proliferation

- Orphan Drugs

- Presentations

- Public Goods

- Research and Development

- Site Articles

- Transparency

- WHAT THEY ARE SAYING: Doug McKalip Confirmed as USTR Chief Agricultural Negotiator

- Statement from Ambassador Katherine Tai Following Doug McKalip’s Senate Confirmation Vote

- Statement from USTR Spokesperson Adam Hodge

- USTR Announces Additional Senior Staff Members

- United States Requests New USMCA Dispute Consultations on Canadian Dairy Tariff-Rate Quota Policies

- Readout of Ambassador Jayme White’s Meeting with Mexico’s Under Secretary of Economy Alejandro Encinas

- Ambassador Tai Requests USITC Investigation of COVID-19 Diagnostics and Therapeutics

- Joint Statement from Ambassador Tai and Secretary Vilsack after Meeting with Mexican Government Officials

- USTR Extends Exclusions from China Section 301 Tariffs

- Joint USTR and Department of Commerce Readout of the First Indo-Pacific Economic Framework Negotiating Round

- Statement by Ambassador Katherine Tai on the Signing of the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation for Trade and Investment Between the United States and the African Continental Free Trade Area

- Readout of Ambassador Katherine Tai and Ambassador Sarah Bianchi’s Events on Day Two of the U.S. – Africa Leaders Summit

- Readout of the African Growth and Opportunity Act Ministerial During the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit

- Readout of Ambassador Katherine Tai’s Meeting With Kenya’s Ministry of Investments, Trade and Industry, Cabinet Secretary Moses Kuria

- What They Are Saying: Ambassador Katherine Tai Confirms Amendments to the Beef Safeguard Trigger Level Under the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement

- Protocol Amending the Beef Safeguard Provisions of the U.S.-Japan Trade Agreement to Enter into Force on January 1, 2023

- Readout of Ambassador Katherine Tai's Meeting with Canada's Minister of Labor Seamus O'Regan

- United States and Bangladesh Convene 6th Meeting of the U.S.-Bangladesh Trade and Investment Cooperation Forum Agreement Council

- Joint Statement on the Third Meeting of the United States – Argentina Council on Trade and Investment

- United States and Panama Hold the Third Meeting of the Environmental Affairs Council under the United States-Panama Trade Promotion Agreement

U.S. to Support Extension of Deadline on WTO TRIPS Ministerial Decision; Requests USITC Investigation to Provide More Data on COVID-19 Diagnostics and Therapeutics

- U.S.-EU Joint Statement of the Trade and Technology Council

- USTR, Department of Labor, European Commission Host Inaugural Principals’ Meeting of the U.S.-EU Trade and Labor Dialogue with Union, Business Leaders

- United States and European Union Conclude First Ministerial Meeting of the Large Civil Aircraft Working Group

- United States and Peru Hold Meetings of the Environmental Affairs Council and the Sub-Committee on Forest Sector Governance under the United States-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement

- Readout of Ambassador Katherine Tai's Meeting with Mexico’s Secretary of Economy Raquel Buenrostro

- PRESS ADVISORY: Media Registration for Third U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council Ministerial Meeting

- Policy Offices

- Press Office

- Press Releases

December 06, 2022

USTR releases summary of five-month consultation on extending WTO TRIPS decision showing broad divergence of views

WASHINGTON – The Office of the United States Trade Representative today announced support for extending the deadline to decide whether there should be an extension of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement (Ministerial Decision) to cover the production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics. USTR also announced that it will ask the United States International Trade Commission (USITC) to launch an investigation into COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics and provide information on market dynamics to help inform the discussion around supply and demand, price points, the relationship between testing and treating, and production and access.

“Over the past five months, USTR officials held robust and constructive consultations with Congress, government experts, a wide range of stakeholders, multilateral institutions, and WTO Members,” said Ambassador Katherine Tai. “Real questions remain on a range of issues, and the additional time, coupled with information from the USITC, will help the world make a more informed decision on whether extending the Ministerial Decision to COVID-19 therapeutics and diagnostics would result in increased access to those products. Transparency is critical and USTR will continue to consult with Congress, stakeholders, and others as we continue working to end the pandemic and support the global economic recovery.”

Supporters and opponents of extending the Ministerial Decision to COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics provided extensive views and arguments. USTR officials also reviewed and analyzed published information, opinions, and analysis. In both cases, the views concern both the system as a whole – whether existing WTO intellectual property protections are an impediment to access to medicines or a critical element of innovation – as well as the specific characteristics of the markets for COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics.

The United States respects the right of its trading partners to exercise the full range of existing flexibilities in the TRIPS Agreement, such as in Articles 30, 31, and 31 bis , and the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, as well as the flexibilities in the Ministerial Decision. These existing flexibilities are available as part of the effort to scale up the production and distribution necessary to overcome the challenges of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on available data and public input, the USITC study will explore key issues such as:

- An overview of the products, focusing on WHO-approved COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics, including key components, the production process, intellectual property protections, and a description of the supply chain (including the level of diversification in the supply chain);

- Information on the global manufacturing industry for these products, including information on key producing countries, major firms, and production data, if available;

- Information on the global market for COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics, including information on demand and, to the extent practicable, an assessment of where unmet demand exists for key products and contributing factors; market segmentation; and supply accumulation and distribution;

- Data and information on global trade in COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics, if available, or if not, data and information on global trade in diagnostics and therapeutics generally; and

- A brief overview/background of the relevant aspects of the TRIPS Agreement and the United Nations (UN) Medicine Patent Pool (MPP) and a listing of countries seeking to use the Ministerial Decision and those utilizing access to COVID-19 medicines under the MPP.

As part of the Administration’s comprehensive effort to combat the pandemic, the United States supported negotiations that resulted in the WTO issuing the Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement on June 17, 2022. Since then, USTR officials consulted with Members of Congress and more than two dozen stakeholders, including public health advocates, organized labor, academics, think tanks, companies, and trade associations. USTR has summarized the diverse views heard during the five-month consultation period.

- 600 17th Street NW

- Washington, DC 20508

- Reports and Publications

- Fact Sheets

- Speeches and Remarks

- Blog and Op-Eds

- The White House Plan to Beat COVID-19

- Free Trade Agreements

- Organization

- Advisory Committees

- USTR.gov/open

- Privacy & Legal

- FOIA & Privacy Act

- Attorney Jobs

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, the role of fast payment systems in addressing financial inclusion, modernizing army software acquisition: panel discussion with dasa(sar) margaret boatner and peo iew&s bg ed barker, book event: the mountains are high, energy security and geopolitics conference.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Transnational Threats Project

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

TRIPS Waivers and Pharmaceutical Innovation

Blog Post by Chris Borges

Published March 15, 2023

By Christopher Borges

On June 22, 2022, the World Trade Organization (WTO) approved a waiver of intellectual property (IP) protections for COVID-19 vaccine patents, previously secured under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). The WTO is currently considering expanding this waiver to include COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics in addition to vaccines. As the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) investigates the implications of this expansion, it is important to understand what this waiver is intended to accomplish, explore whether it will be effective in the short term, and examine the long run impacts on the bio-pharmaceutical innovation system.

What Is the TRIPS Agreement?

TRIPS refers to a WTO agreement incorporating obligations related to IP protection into the global rules-based trading system. Active since 1995, TRIPS requires most WTO members to adhere to minimum rules for the protection of IP — such as patents, copyrights, and trademarks — and enforce these commitments domestically. By agreeing to respect IP protections, member countries receive certain benefits in return. For example, TRIPS allows WTO members to make exceptions to patent rights so long as they are “limited” and do not violate the “normal” use of the patent. States often employ this provision to advance their science and technology base by allowing their researchers to use patented research tools and techniques.

Why Was There a Call to Waive TRIPS IP Protections for COVID-19 Vaccines?

Despite COVID-19 vaccines being the fastest developed vaccines in history, global access to these vaccines remains uneven. The United States first administered COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020, yet, per the University of Oxford, as of March 1st, 2023, only 28 percent of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Most of the vaccines approved for use are developed by firms in the United States, Europe, China, and Russia, but the Western-made mRNA vaccines are the most effective and therefore the most in-demand vaccines on the market. The wealth of Western nations along with the geographic distribution of mRNA vaccine producers enabled them to reserve large vaccine supplies early in the pandemic, effectively shutting out lower-income countries. Low-income countries currently have a 28 percent vaccination rate, whereas the United States had vaccinated 28 percent of its population by March 23rd, 2021.

Citing this disparity, many developing nations called on the international community to waive TRIPS IP protections for COVID-19 vaccines, based on the notion that allowing any company to manufacture the vaccines will boost production and, ultimately, vaccinations. South Africa and India first proposed a TRIPS waiver for COVID-19 vaccines in October 2020, drawing considerable support from over 100 lower-income countries. High-income countries, however, were initially opposed to the waiver on the grounds that it would have an adverse effect on innovation, drug quality, and drug safety. Negotiations continued for nearly two-years until the waiver was ultimately agreed to, with high-income countries easing their objections once they were sufficiently supplied with vaccines.

What Does the COVID-19 Vaccine Waiver Do?

The COVID-19 vaccine waiver suspends certain requirements regarding the use of COVID-19 vaccine patents, such as ingredients and manufacturing processes. With this waiver, states can authorize domestic manufacturers to produce COVID-19 vaccines without the permission of the patent rights holder and, crucially, to export those vaccines to other countries.

The waiver was designed to be a short term action, taken as an emergency measure in the midst of a global pandemic. However, as implementing the waiver required all 164 WTO members to agree, it took nearly two years of deliberation to come to consensus. By the time WTO members agreed to the waiver in June 2022, the response to the pandemic had progressed considerably and over 12 billion vaccine doses had been administered.

Why Are There Calls to Expand the TRIPS Waiver?

The WTO is currently considering if the waiver should be expanded to include the production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics. This would cover a broad category of products, including products utilized for diseases and conditions beyond COVID-19.

To date, the FDA has approved dozens of COVID-19 therapeutics. Oral antiviral treatments paxlovid and molnupiravir were quickly developed by Pfizer and Merck, respectively, and approved by the FDA in late 2021. Remsidivir, a therapeutic first developed in 2009 by Gilead Sciences, was repurposed to treat COVID-19 after studies concluded that it reduces the risk of hospitalization and death in high-risk patients by up to 87 percent.

The efficacy of these COVID-19 treatments prompted low-income countries and international organizations such as UNICEF to demand an expansion of the TRIPS waiver to include these drugs along with diagnostic tests. To continue combating COVID-19 — the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 70,000 new cases on March 1st — they assert that all medical tools must be made available to the fullest extent.

How Effective Is the TRIPS Waiver? How Effective Would the Expansion Be?

The COVID-19 TRIPS waiver has had minimal impact on overall vaccine access. As of the end of 2022, no country had declared intent to make use of the TRIPS waiver.

Global vaccine demand had plummeted by the time the TRIPS waiver was agreed to. In December 2022, the board of Gavi, a nonprofit that supplies vaccines to low- and middle-income countries voted to stop supplying COVID-19 vaccines to most nations due to lack of demand. This drop in demand indicates that the primary issue impeding vaccinations today is not lack of supply, but lack of distribution capacity. Administering COVID-19 vaccines across a population requires significant healthcare infrastructure which some developing countries lack , such as refrigeration to keep vaccines at low temperatures and a well-trained healthcare workforce. To increase global vaccination rates, efforts should focus on building healthcare infrastructure and distribution capacity, not facilitating additional vaccine production.

Currently, the supply of treatments to COVID-19 far outstrips demand as well. This is largely because secure IP rights have incentivized drug inventors to enter over 140 partnerships with manufacturers worldwide, boosting supply while transferring technology and tacit knowledge to these foreign firms. Secure IP rights assure companies that their inventions will not be stolen in the short-term, thereby allowing them to reveal their secrets and participate in these productive manufacturing partnerships. Expanding the TRIPS waiver to therapeutics would have little added benefit to access.

Further, expanding the TRIPS waiver to therapeutics will disincentivize the creation of new COVID-19 treatments. Biopharmaceutical research is expensive and risky — the R&D process for new drugs costs close to $1 billion on average, and only 12 percent of drugs which enter clinical trials are ultimately approved for use. Companies will simply not invest in creating new therapeutics if they will lose ownership of their IP should their huge and risky investment prove fruitful.

Can the COVID-19 TRIPS Waivers Damage the Biopharma Innovation Ecosystem?