What Are Intangible Services in the Tourism Industry?

By Alice Nichols

Intangible Services in the Tourism Industry

The tourism industry is one of the largest and fastest-growing industries in the world. It encompasses a wide range of products and services, including transportation, accommodation, attractions, activities, and more.

However, not all tourism products are tangible or physical. There are also intangible services that play a vital role in the tourism industry. In this article, we will explore what intangible services are in the tourism industry and why they matter.

What Are Intangible Services?

Intangible services are non-physical products that cannot be touched or perceived by the senses. They are often referred to as “non-material” or “immaterial” goods because they do not have a physical presence. Examples of intangible services in the tourism industry include:

- Information and Knowledge: Tourists need information about destinations, attractions, activities, events, and other aspects of their trip. This information can be provided through brochures, guidebooks, maps, websites, social media platforms, and other means.

- Counseling and Advice: Tourists often require counseling on travel-related matters such as visa requirements, health risks etc. Travel agents and other travel professionals provide counseling services to tourists.

- Booking and Reservation: Tourists book hotels rooms , flights , tours , cars etc . This service is provided by online travel agents (OTAs), tour operators or directly from suppliers websites.

Why Do Intangible Services Matter?

Intangible services play a critical role in the tourism industry. Here are some reasons why:

Enhancing Tourist Experience

Intangible services help to enhance the tourist experience by providing them with useful information, advice, and support. Tourists who are well-informed and feel supported during their trip are more likely to have a positive experience and return as repeat customers.

Building Trust and Credibility

Intangible services help to build trust and credibility between tourists and tourism stakeholders such as travel agents, tour operators, hotels, etc. Tourists who receive high-quality intangible services are more likely to trust the recommendations and advice of travel professionals and other stakeholders.

Adding Value to Tourism Products

Intangible services add value to tangible tourism products such as accommodation or transportation. For example, a hotel that provides excellent customer service through its staff is more likely to attract repeat customers than a hotel with poor customer service.

The Bottom Line

Intangible services are an essential component of the tourism industry. They provide tourists with valuable information, advice, support, and other non-physical products that enhance their travel experience.

The success of the tourism industry depends on the quality of these intangible services provided by various stakeholders such as travel agents, tour operators, hotels etc.

10 Related Question Answers Found

What are ancillary services in tourism, what are ancillary services in tourism examples, what is tangible and intangible in tourism, what are the services in tourism industry, what are the services in tourism, what are the services offered in the tourism industry, what are services in tourism, what are travel services in tourism, what is tourism and travel services, what are the services of tourism, backpacking - budget travel - business travel - cruise ship - vacation - tourism - resort - cruise - road trip - destination wedding - tourist destination - best places, london - madrid - paris - prague - dubai - barcelona - rome.

© 2024 LuxuryTraveldiva

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 8. Services Marketing

8.2 Differences Between Goods and Services

There are four key differences between goods and services. According to numerous scholars (cited in Lovelock & Patterson, 2015) services are:

- Heterogeneous

- Inseparable

The rest of this section details what these concepts mean.

Intangibility

Tangible goods are ones the customer can see, feel, and/or taste ahead of payment. Intangible services, on the other hand, cannot be “touched” beforehand. An airplane flight is an example of an intangible service because a customer purchases it in advance and doesn’t “experience” or “consume” the product until he or she is on the plane.

Heterogeneity

While most goods may be replicated identically, services are never exactly the same; they are heterogeneous . Variability in experiences may be caused by location, time, topography, season, the environment, amenities, events, and service providers. Because human beings factor so largely in the provision of services, the quality and level of service may differ between vendors or may even be inconsistent within one provider. We will discuss quality and level of service further in Chapter 9.

Inseparability

A physical good may last for an extended period of time (in some cases for many years). In contrast, a service is produced and consumed at the same time. A service exists only at the moment or during the period in which a person is engaged and immersed in the experience. When dining out at a restaurant, for instance, the food is typically prepared, served, and consumed on site, except in cases where customers utilize takeout or food courier options such as Skip the Dishes.

Perishability

Services and experiences cannot be stored; they are highly perishable . In contrast, goods may be held in physical inventory in a lot, warehouse, or a store until purchased, then used and stored at a person’s home or place of work. If a service is not sold when available, it disappears forever. Using the airline example, once the airplane takes off, the opportunity to sell tickets on that flight is lost forever, and any empty seats represent revenue lost (Figure. 8.4).

Untouchable: a characteristic shared by all services.

Variable: a generic difference shared by all services.

In relation to goods and services. Services cannot be separated from the service provider as the production and consumption happens at the same time.

Something that is only good for a short period of time, a characteristic shared by all services.

Goods the customer can see, feel, and/or taste ahead of payment.

Introduction to Tourism and Hospitality in BC - 2nd Edition Copyright © 2015, 2020, 2021 by Morgan Westcott and Wendy Anderson, Eds is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.2: Differences Between Goods and Services

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9346

- Morgan Westcott & Wendy Anderson et al.

There are four key differences between goods and services. According to numerous scholars (cited in Lovelock & Patterson, 2015) services are:

- Heterogeneous

- Inseparable

The rest of this section details what these concepts mean.

Intangibility

Tangible goods are ones the customer can see, feel, and/or taste ahead of payment. Intangible services, on the other hand, cannot be “touched” beforehand. An airplane flight is an example of an intangible service because a customer purchases it in advance and doesn’t “experience” or “consume” the product until he or she is on the plane.

Heterogeneity

While most goods may be replicated identically, services are never exactly the same; they are heterogeneous. Variability in experiences may be caused by location, time, topography, season, the environment, amenities, events, and service providers. Because human beings factor so largely in the provision of services, the quality and level of service may differ between vendors or may even be inconsistent within one provider. We will discuss quality and level of service further in Chapter 9.

Inseparability

A physical good may last for an extended period of time (in some cases for many years). In contrast, a service is produced and consumed at the same time. A service exists only at the moment or during the period in which a person is engaged and immersed in the experience. When dining out at a restaurant, for instance, the food is typically prepared, served, and consumed on site, except in cases where customers utilize takeout or food courier options such as Skip the Dishes.

Perishability

Services and experiences cannot be stored; they are highly perishable. In contrast, goods may be held in physical inventory in a lot, warehouse, or a store until purchased, then used and stored at a person’s home or place of work. If a service is not sold when available, it disappears forever. Using the airline example, once the airplane takes off, the opportunity to sell tickets on that flight is lost forever, and any empty seats represent revenue lost (Figure. 8.4).

- Toggle navigation

HMGT 4702 Hospitality Services Marketing Management

Professor ellen kim.

Nature of Services

- 1 Nature of Services

- 2 The Service Economy

- 3 The Role Of the Service Economy In Development

- 4 Services as Solutions

- 5.1 It’s about selling a meaningful solution bundle

- 5.2 It’s about customer engagement

- 6 Services as Products

- 7 Starbucks Experiences

Nature of Services

- Intangibility : services cannot be seen, felt, tasted, or touched in the same manner that we can sense tangible goods.

- Inseparability : services cannot be separated from the person or firm providing it.

- Variability : Since services are performances, frequently produced by human beings, no two services will be precisely alike. Services are heterogeneous across time, organizations, and people and as a result, it is very difficult to ensure consistent service quality.

- Perishability : services cannot be saved, stored, resold, or returned.

The Service Economy

The world economy is increasingly characterized as a service economy. This is primarily due to the increasing importance and share of the service sector in the economies of most developed and developing countries. In fact, the growth of the service sector has long been considered as an indicator of a country’s economic progress. Economic history tells us that all developing nations have invariably experienced a shift from agriculture to industry and then to the service sector as the mainstay of the economy. This shift has also brought about a change in the definition of goods and services themselves.

Service organizations vary widely in size. At one end of the scale are huge international corporations operating in such industries as airlines, banking, insurance, telecommunications, and hotels. At the other end of the scale are a vast array of locally owned and operated small businesses, such as restaurants, laundries, optometrists, beauty parlors, and numerous business-to-business services.

The service sector is going through revolutionary change, which dramatically affects the way in which we live and work. New services are continually being launched to satisfy our existing needs and to meet needs that we did not even know we had. Nearly fifty years ago, when the first electronic file sharing system was created, few people likely anticipated the future demand for online banking, website hosting, or email providers. Today, many of us feel we can’t do without them. Similar transformations are occurring in business-to-business markets.

The Role Of the Service Economy In Development

As of 2008, services constituted over 50% of GDP in low-income countries. As their economies continue to develop, the importance of the service sector continues to grow. For instance, services accounted for 47% of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa over the period 2000–2005, while industry only contributed 37% and agriculture only 16% in that same period. This means that recent economic growth in Africa relied as much on services as on natural resources or textiles, despite many of those countries benefiting from trade preferences in primary and secondary goods.

As a result of these changes, people are leaving the agricultural sector to find work in the service economy. This job creation is particularly useful as often it provides employment for unskilled workers in the tourism and retail sectors, which benefits the poor and represents an overall net increase in employment. The service economy in developing countries is most often made up of the following industries: financial services, tourism, distribution, health, and education.

Services as Solutions

If you want customers to buy your services, you need to offer them a solution that costs less than the problem is costing them. Your solution might:

- Save your customer money;

- Save your customer time: or

- Improve your customer’s productivity.

This is different from solution selling because instead of defining the solution and then looking for applicable problems, you are tailoring your services to fit your prospective customer’s day-to-day problems. In essence, you are in the problem-solving business and if you can prove that you can solve your customer’s present problems, you’ll have a long-term customer who will come back for more and more.

In order to accomplish this task you and anyone involved in selling your services need to:

Have an excellent understanding of the services you’re offering and what can and can’t be tailored to a customer’s requirement;

- Have a solid understanding of the common problems your prospects face and those that your services can solve; and

- Prepare 20-25 questions to identify possible problems and generate credibility and confidence in your company’s abilities.

Selling Services As Solutions

Without genuinely valuable services for your customer, you have no revenue. While “what’s the value proposition? ” is an over-used term, below is a more specific definition of value, particularly as it applies to application software (in contrast with infrastructure software).

It’s about selling a meaningful solution bundle

When selling services rather than technology, the focus should be on people and organizations—listening to and understanding their internal projects and being considerate of their timelines and budgets . It is important to listen and provide a fair offer for services that genuinely meet a customer’s need. Budgets are much too constrained these days for anyone to buy services they don’t really need. This model can be a good foundation for a company, leading to a sustainable revenue stream that can help to further fund the development of the product.

In other words, create revenue that can sustain and grow the business, to make the product better in the long run, and to enable customers to better deploy the software. This only happens if the software and the services provide real value to an organization.

It’s about customer engagement

Years ago, the Red Hat Network offered a valuable service for those who purchased a software subscription. If you passively wait for the renewal, you can expect that some customers will ask themselves, “Do we use this subscription service or not? Do we really need to continue to pay for it? ” A proactive approach in this scenario is to demonstrate ongoing value by regular customer engagement, showing the customer new features they can access via their subscription, reviewing their current use of the product, and offering add-on services to help them be better trained or better able to use more of the product for more of their organization.

The fundamental principle here is value. No customer will renew a subscription service or buy more consulting services if they don’t see genuine value in these services as it relates to fulfilling their business objectives, whether that be better customer service , better IT responsiveness, or better IT management.

Services as Products

The increasing importance of the service market in the economy has brought about a change in the definition of goods and services. No longer are goods considered separate from services. Rather, services now increasingly represent an integral part of the product. It is this interconnectedness between goods and services that is represented on a goods-services continuum.

Services can be alternatively defined as products, such as a bank loan or a home security, that are to some extent intangible. If totally intangible, they are exchanged directly from the producer to the user, cannot be transported or stored, and are almost instantly perishable .

Service products are often difficult to identify because they come into existence at the same time that they are bought and consumed. They comprise intangible elements that are inseparable; they usually involve customer participation in some important way; they cannot be sold in the sense of ownership transfer, and they have no title. Today, however, most products are partly tangible and partly intangible, so the dominant form is to classify them as either goods or services (all are products).

The dichotomy between physical goods and intangible services should not be given too much credence. These are not discrete categories. Most business theorists see a continuum with pure services on one terminal point and pure commodity goods on the other terminal point. Most products fall between these two extremes. For example, a restaurant provides a physical good (the food), but also provides service in the form of ambiance, the cooking and the serving of the food, and the setting and the clearing of the table. And although some utilities actually deliver physical goods — like water utilities which actually deliver water — utilities are usually treated as services.

Additional Reading : http://marketingmix.co.uk/

Starbucks Experiences

Source: Boundless. “The Importance of Services.” Boundless Marketing . Boundless, from https://www.boundless.com/marketing/textbooks/boundless-marketing-textbook/services-marketing-6/the-importance-of-services-48/

The OpenLab at City Tech: A place to learn, work, and share

The OpenLab is an open-source, digital platform designed to support teaching and learning at City Tech (New York City College of Technology), and to promote student and faculty engagement in the intellectual and social life of the college community.

New York City College of Technology | City University of New York

Accessibility

Our goal is to make the OpenLab accessible for all users.

Learn more about accessibility on the OpenLab

Creative Commons

- - Attribution

- - NonCommercial

- - ShareAlike

© New York City College of Technology | City University of New York

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.9(1); 2023 Jan

The use of intangible heritage and creative industries as a tourism asset in the UNESCO creative cities network

Jordi arcos-pumarola.

a CETT-UB Barcelona School of Tourism, Hospitality and Gastronomy, Barcelona, Spain

Alexandra Georgescu Paquin

b Canada Research Chair in Urban Heritage ESG-UQAM, Montreal, Canada

Marta Hernández Sitges

Associated data.

Data will be made available on request.

The creative economy has been recognized as key in urban development and planning, which the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN) consolidates. While benefiting from the label, the tourism sector also plays a fundamental role in the creative strategy. This paper explores how intangible heritage and creative industries can work as a tourism asset for creative cities and thus participate in their development. An NVivo thematic content analysis of all the tourism-related actions listed in the UCCN reports was performed to identify what types of cultural tourism products and actions are linked to the creative cities and to understand how they relate to their UNESCO creative fields to detect gaps and potentials. Tourism activity represents 17% of the total actions listed in the creative cities’ reports, mostly concentrated in the Crafts & Folk Art field. The empirical results highlight tendencies that can be applied and adapted to future destinations with intangible assets on their territory and that want to work with the creative industries. Thus, this paper unveils an underexplored potential of synergies between two important economic and creative activities.

1. Introduction

During the last decades, the importance of the creative industries has been increasing in the sustainable development of the cities, as the recognition of the 2021 International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development shows. Cultural and creative industries are based on diverse sectors and activities “whose principal purpose is production or reproduction, promotion, distribution, or commercialization of goods, services, and activities of cultural, artistic, or heritage-related origins” [ 1 ], p.11]. Launched in 2004, UNESCO's Creative Cities Network (UCCN) strengthens cooperation between public, private, and civil society sectors, with culture as a driving force for development. UNESCO's Creative Cities Network divides its label into seven creative fields: Crafts and Folk Arts, Design, Film, Gastronomy, Literature, Media Arts and Music.

The tourism sector is included in the creative cities' development through products that differentiate the destination and are directly linked to local and territorial characteristics. For example, the city of Burgos, a creative city of gastronomy, has positioned itself around healthy gastronomy and has focused on tourism promotion based on this resource. The cases of Edinburgh and Barcelona (both cities of Literature) are also interesting [ 2 ] because they joined their creative field with tourism products or promotion, such as different literary festivals and itineraries based on novels or their authors. As it is a great instrument for destinations' competitiveness [ 3 ], the alignment of creative industries with the tourism sector is continuously increasing. For example, Barcelona's city council aims to integrate the city's creative industries within the destination narrative account through a political policy [ 4 ]. The forced hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic has given destinations the occasion to rethink the different strategies and proposals to find alternatives to mass tourism for a more sustainable, creative, and experiential model [ 5 ].

The synergies between creative industries and tourism take root in cultural tourism, which has been experiencing a transformation since the beginning of the 21st century [ 6 , 7 ]. Cultural tourism was historically based mainly on tangible assets; nevertheless, these assets grew in diversity, from monuments or museums to heterogeneous elements like contemporary art [ 8 ]. Moreover, the contemplation of tangible culture has turned into a more active interaction, where visitors are now part of the co-creation of the experience. Nowadays experiences are at the center of tourism demand [ 9 ], making the trip unique and personalized . Interactive or sensory experiences provide them with unique memories, like a “mental souvenir” [ 10 ], as well as an anchored vision of the territory through its cultural features.

The shift from an economy based on products and services to an economy based on experience, where visitors live a memorable stay that can transform their way of thinking and acting, is at the center of the “creative turn of tourism” [ 11 ]. Creative industries bring a paradigm shift in tourist activity, and more specifically in cultural activity, by contributing to these experiences. In 2020 a European project called Traces–Cultour Is Capital [ 12 ] was initiated between eight European countries to involve the tourism and creative industries sectors in laboratories where local resources would be used to shape innovative tourist products. The synergies that are established between the two sectors are the pillars of the project and announce a powerful potential for the cities’ development and tourism offer. In this context, cultural capitalization is one of the more effective tools to project uniqueness and augment competitiveness amongst destinations through their differentiation [ 13 ].

The creative industries are very diverse and include also the intangible assets of a territory, such as heritage. Intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is not only a representation of the past and its tradition but also a strong pillar for development and creativity. Indeed, some ICH are represented as a creative field in the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, or UCCN [ 14 ], such as Crafts & Folk Art or Gastronomy. Also, their impact on tourism was recognized in the first UNWTO Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage [ 15 ], following the World Tourism Day 2011 on “Tourism–Linking Cultures”. The report demonstrates how ICH can benefit the local community by also involving them, like with “Handicrafts and visual arts that demonstrate traditional craftsmanship”. At the same time, the report shows the challenges of converting ICH into tourism products, especially when language or big cultural gaps impose their limits: the ICH category “Oral Traditions and Expressions, including Language as a Vehicle of Intangible Cultural Heritage”, since it depends on languages, is more complex to divulge to the international public.

Creative industries and intangible heritage can play a foremost role within the strategic plans for post-pandemic tourism since they can contribute to improving tourism management and to the creation of new attractive spaces for creative workers, tourists, and residents. This way, their contribution to placemaking [ 16 , 17 ] and the creation of new experiences may help in the redistribution of tourism activity. Moreover, they also contribute to the creation and attraction of festivals or events that motivate the movement of visitors. Nevertheless, the broad scope of the notion of creative industries, as well as the different realities included within this concept, might complicate the development of concrete tourism products or strategies based on a particular creative industry.

The impact of creative industries and tourism on the development of the cities, heritage, and their branding has been researched through case studies focusing on the UCCN label [ 18 ], or by applying indicators [ 19 , 20 ]. However, the consideration of the tourism sector as part of the strategy of the Creative Cities and not only as the outcome of the label has not been explored yet, moreover in a transversal way through all the seven UCCN creative categories. This paper aims to fill this gap through the analysis of concrete actions that are undertaken by the city members of the UCCN related to tourism. It aims at unveiling the relationship between creative industries and tourism in specific creative fields to understand the potential that these sectors can bring to the development of creative cities. This paper also contributes to the literature on the synergies between intangible heritage, creative industries, and tourism as part of a global movement for a more sustainable cultural tourism model.

2. Creative industries as a generator of creative tourism

Creativity as a key tool in tourism can provide singular and memorable experiences and increase tourism competitiveness [ 3 ]. To understand the synergies and potential between creativity and tourism, the first section of the literature review explores the characteristics of tourism development based on creative industries. The other section shows tourism products or strategies generated by this synergy.

2.1. Creativity and tourism experience

The creative industries and tourism are increasingly important in city strategies. For more than a decade, culture has become a central element of the strategies of many destinations, both in terms of their development and their appeal [ 21 , 22 ]. In fact, destinations use creativity in their tourism strategies to increase their competitiveness [ 23 ].

The creative industries have progressively and successfully incorporated the tourism sector: “The creativity of the tourist is achieved less directly through exposure to creative atmospheres such as being present in creative events, places or atmospheres as creative clusters” [ 24 ], p. 19]. In the context of the experience economy defined by Pine and Gilmore [ 9 ], tourists are consumers of memorable experiences through attractive goods and services. According to Pérez-Martínez and Dolader [ 25 ], the main characteristic of experiential tourism is the tourists' involvement in the services or goods that are provided. Moreover, creativity is a powerful tool for the creation of unique and singular experiences, one of the reasons being the “active forms of involvement by tourists in the everyday life of destinations” [ 11 ], p.12333]. In that sense, the definition pinned by UNESCO during its international conference focuses on the educational, emotional, social, and participatory interaction with the destination: creative tourism is “travel directed toward an engaged and authentic experience, with participative learning in the arts, heritage, or special character of a place, and it provides a connection with those who reside in this place and create this living culture” [ 26 ], p.3]. Thus, this connection creates a social impact by also providing a sense of belonging to a community through the visitors’ involvement. Finally, the personalization of services and goods as well as learning through experience are also key to experiential tourism.

Moreover, for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [ 27 ], the connection between tourism and the creative industries has great potential that is not limited to the generation of tourist experience demand. They state that the synergies between tourist activity and creativity could contribute to the destination's image-building and promotion, the development of small-scale creative businesses and spaces, the generation of an attractive atmosphere, and the attraction of talent to foster the relationship between tourism and the creative industries or raise awareness of local culture, among others.

Creative tourism, by its close relationship with the territory and its local assets, can contribute to the prevention of the homogenizing effects of globalization and the “spectacularization” of society [ 28 ] by generating unique experiences. The unique experiences derived from creativity and tourism are based on the “EUA” triad composed of “Engaging”, “Unique” and “Authentic” [ 29 ]. The author refers to “Engaging” when the experience takes the senses, and the user dives into the experience, allowing the user to escape reality. It is “Unique” when the user perceives that what is experienced cannot be repeated, i.e. is singular. And finally, it is “Authentic” when it is original and based on the specificities of local heritage. These elements ensure success in the holistic tourist experience that the creative industries and intangible heritage can generate. Although the definition of cultural tourism is far from having reached a consensus, some characteristics, like authenticity, experience and co-creation are accepted and adapted in a constantly changing context [ 30 ].

Creative tourism was first named in Pearce and Butler [ 31 ] as a potential form of tourism and was further developed as a concept by Richards and Raymond [ 32 ] as one that offers visitors the opportunity to develop their creative potential by actively participating in the learning experiences based on a local heritage asset or knowledge that characterizes the destination. Thus, it presents an integrative experience that allows direct interaction between the visitor and locals, as well as the destination's culture, providing the tourist with meaning through cultural exchange [ 33 ]. However, some studies highlight a discrepancy between developers and creatives regarding the relationship between creative's work and tourism, putting this sector in a “blind spot in the business practices of creative entrepreneurs” [ 34 ].

Among the different perspectives of the concept, Carvalho et al. [ 24 ] focus on the co-creation process, whereas the relationship with the cultural and creative industries is also explored as a framework to develop these experiences [ [35] , [36] , [37] , [38] ]. In that context, the natural and cultural assets of a territory are not meant to be “exploited”, but enhanced and optimized [ 19 ]. In this sense, it contributes to the development of an “orange” economy, a model that transforms ideas and goods into cultural and creative services in a sustainable way. Indeed, because the creative approach to tourism is respectful of its surroundings and employs local businesses and resources which can conciliate their primary activity with tourism [ 39 ], it offers a great development tool for destinations as a “means of increasing social and relational capital, both for tourists and (local) providers” [ 37 ], p.5].

Intangible heritage resources and the creative industries also offer great potential to develop tourism products and experiences based on traditions, narratives, atmospheres, imagination, and creativity [ 24 ]. Different creative industries are directly linked to creating tourism products or experiences. According to Rodríguez [ 13 ], it is also a growing trend that fosters gastronomy and art products. However, because a tourism product requires a certain infrastructure and are aimed at being communicated and consumed by a visitor that does not necessarily hold the keys to its comprehension, some creative domains are more prone to be converted into tourism product than others.

2.2. Tourism products based on creative industries

Creative industries contribute to the creative economy by using, “as input or as an end, artistic-cultural production, involving handicrafts, popular manifestations, and popular festivals, museums, music, performing arts, visual arts, literature, book publishing, radio and tv, cinema, digital games, fashion, gastronomy, architecture, among other segments” [ 2 ], p. 166]. Some have direct links to a specific cultural tourism form, like film and literature tourism. Both are based on two industries that use fiction as a driver to “transport” the visitors in a dimension that convenes their memories and the emotions experienced, which will be compared during their visit [ 40 ]. Likewise, video games form an emerging tourism type that is gaining importance for the experiences that it provides [ 41 ]. Others, like the design or fashion industries, provide events such as festivals. Also, experts consider that creativity is a strong ally to intangible heritage because “models of cultural tourism based on tangible heritage are being augmented by growth in intangible heritage and creativity” [ 15 ], p. 12].

A creative economy might be a source from which to develop tourism products that enhance the destination's narrative, as well as contribute to the redistribution of tourism activity within the city [ 42 ]. The creative tourism model exposed by Carvalho et al. [ 24 ] which is imported from the creative cities, takes into account the spatiality of creative tourism in its three fields of applications.

- 1. Events, Festivals and Creative Spectacles, as a direct link between creative industries, creativity, and tourism;

- 2. Creative spaces, redefining the spaces' functions as well as creating creative clusters;

- 3. Creative networks and creative itineraries.

In the first category, “Events, Festivals and Creative Spectacles”, the public live an experience that is both collective and intimate. The public lives a powerful experience because it is shared collectively as a cultural event, such as listening to music, watching art, etc. Therefore, it generates a context of collective emotions that are lived together with a group, making the experience enhanced by having shared it [ 43 ]. Therefore, on the one hand, a sensory and intimate relationship is established with the cultural event itself, shared with a community that has the same interests and motivations. In this way, the live experience as well as the memory of it are enhanced. On the other hand, another type of relationship is created by the personal experience lived by every spectator, thus generating a connection between the spectator and the artist. Festivals have the particularity of being recurrent, which also helps to build a destination brand (Cannes Film Festival, Edinburgh Festival Fringe, etc.). However, some events can be created as a “pop-up event”, which is intended as a temporary one, and also impact the city, for example, as a placemaking tool.

Indeed, as we see in the second category, these events are also a powerful placemaking tool in redefining and dynamizing public spaces, contributing to the dispatching of visitor flows in different zones of the city. But placemaking is more than shaping cities: as Soja [ 44 ] argued with the concept of “Thirdspace”, it is not just the physical reality of the city that matters, but also the way that reality is represented and lived or experienced. Creative Placemaking is an evolving field that comprehends the arts, culture, and creativity as a tool in a community's interest. Creative placemaking also contributes to change, growth, and transformation by building the character and quality of a place [ 45 ]. Indeed, the creative economy can add value through products and content, as well as by making these sites more distinctive and attractive [ 46 ]. This benefits the resident first and, by extension, the tourist. The clusters and hubs that have been created, like 22@ in Barcelona, are examples of attraction pools for exterior investments as well as local businesses and artists that cohabitate in an innovative and inspiring urban area. Professional events, such as conferences, gatherings, and residencies, are a significant showcase for a destination. Therefore, creative industries have an important component that influences the quality of life of everyone who shares such a space, and who appropriates it. Responding to economic logic, the creation of space clusters, which bring together creative producers and artisans, provides a creative environment for tourist consummation [ 17 ].

Finally, the third field of application refers to the definition of creative tourism seen before, as well as creative itineraries, like in film or literary tourism, which base their itineraries on scenes that appear in the stories or on elements that are part of the author's biography, like their house. This type of creative itinerary appears in the form of complementary tourism offers that also shape the image of the destination. After seeing a movie that has an impact on someone, the next natural step would be to visit the place to know, live, and experiment with it [ 47 ]. The dialogue between tourism and fiction attracts potential visitors by preparing their visit with images that, during their stay, can be compared, reviewed, and lived in the first person, or also revisited after the trip.

These three fields of application encompass the tourism products based on ICH and are detailed in the UNWTO Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage report [ 15 ]. According to the report, these products can be developed through.

- • Creating cultural spaces or purpose-built facilities as venues to showcase ICH: Museums, or interpretation centers, can either collect objects that represent tradition (ethnological museums, for example) or offer a gastronomic experience that also dynamizes the territory [ 48 ]. Some other cultural spaces are, like in literary tourism, linked to the life of an author or the locations of its fiction.

- • Combining or bundling attractions to create a themed set for stronger market appeal: for example, wine tourism creates itineraries, visits to cellars, and tasting, thus working with different actors. Partnerships and innovative initiatives are particularly relevant to create strong and sustainable tourism products, as well as promoting entrepreneurship [ 49 ].

- • Developing new tour routes, circuits, or heritage networks, as well as using existing circuits or reviving networks, such as pilgrimage routes: new routes can lead to opening new public segments and being more inclusive [ 50 ].

- • Using or reviving festivals and events: These tourism-related products were particularly limited or canceled during the pandemic. A change in their management and a reformulation of their format, for example, to avoid overcrowding, have been identified as a challenge to address in the post-COVID-19 era [ 51 ].

Within ICH categories, the report states that “Gastronomy and Culinary Practices” are mostly represented in festivals like “Music and the Performing Arts”. “Social Practices, Rituals and Festive Events” are linked to traditions or the sacred, which are more delicate when it comes to their commodification in tourism products but can lead to festivals or pilgrimage routes. “Knowledge and Practices Concerning Nature and the Universe” can create itineraries based on transhumance or educational practices for tourists. A decade later, we can argue that the MICE sector (meetings, incentives, conferences, and exhibitions) has a great weight in the tourism strategy of a destination [ 52 ], which can also be linked to the creative industries and intangible heritage. Training and education, offered in these contexts or in mobility strategies, also contribute to dynamizing culture and destinations through tourism.

Tourism, based on creative industries and ICH, can also contribute to the diversification of tourist areas in a city, especially in the pre–COVID-19 context, where many cities, like Barcelona, met the challenge represented by some massified areas. Thus, this type of tourism is presented as an alternative solution to a complementary offer of destinations [ 53 ], or, in the case of territories without a developed tourism industry, as an opportunity to introduce tourism within their economy.

Therefore, the creative industries are generators of creative tourism, either through co-creation projects or by relying on creativity to optimize the tourism asset and convey singular experiences. The challenge is therefore to embody this potential in concrete proposals and actions. Consequently, what kinds of actions do creative cities take with the tourism sector?

3. Research methodology

To answer the research question, exploratory research has been conducted on the UNESCO Creative Cities Network reports. As we detail hereinafter, a thematic classification [ 54 ] based on an inductive method led to highlighting the main actions related to tourism to analyze their tendencies. According to Paillé and Mucchielli [ 54 ], the “themes” (in our case, action categories) were detected in the text after two readings and shared the same fundamental characteristics. The inductive analysis has been carried out using NVivo, a popular software for thematic analysis [ 55 ], which allows an intuitive coding process for qualitative analysis.

UNESCO's Creative Cities Network was created in 2004, but since 2016, the 246 city members have been required to publish a report on their activities every four years after the designation [ 56 ]. In these documents, cities share their experience during the last four years. They explain the major initiatives implemented and actions taken, as well as explain their strategy and plan for the following four-year period linked to the creative field for which they obtained UNESCO's Creative Cities label. These reports are public and represent a fruitful source of examples and monitor good practices in developing their creative industries. Thus, as existing academic literature already shows [ 57 , 58 ], the monitoring reports provide relevant data from which to acquire a comprehensive perspective on the trends and strategies followed by creative cities.

Therefore, the data collection method consisted in retrieving all the tourism actions done by the UNESCO Creative Cities and put in their report. After two rounds of filtering the actions, 321 tourism-related were retrieved in a total of 112 reports, all between the seven UNESCO creative fields.

All the available monitoring reports were downloaded during April 2021 for a first reading of the material to obtain a list of all the developed actions by city members. Of the 246 city members, only 127 reports were available online; the newest members had not published their first report yet, and the older ones might have more than one published. In that case, the analysis was limited to the last published document to focus on the latest actions and strategies led by the cities. Therefore, the corpus was limited to 112 documents. They were divided by their UNESCO creative field label: Crafts and Folk Arts, Design, Film, Gastronomy, Literature, Media Arts and Music. In the 112 documents, every concrete action displayed with a title was retrieved, for a total of 1901 actions.

The second filter is aimed at identifying and isolating the actions developed by creative cities that have a relationship with tourism. To analyze them, NVivo software was used with the following search query: “touris*” or “visit*”, which indicates an action that has a specific intention directed to a public (tourist or visitor). The number of actions obtained after this second step was 321, which represents 17% of the total of actions carried out by UNESCO's Creative Cities, distributed in 92 cities. Those actions are only those related to tourism and constitute the analysis material.

For the data analysis, a typology was elaborated throughout the 321 actions to understand, on the one hand, what are the tendencies followed by the creative cities regarding the type of tourism product, service, or action that are promoted. On the other hand, by crossing the type of actions with the seven UNESCO creative fields labels, the analysis highlights the tendencies, possibilities, and plans according to each field, which might be relevant and inspiring to adapt outside their own.

The typologies were created by adopting an inductive categorization approach. The preliminary categories were applied based on the literature review, mostly inspired by the UNWTO 2012 report, and discussed between the authors to obtain consensus. The criteria were based on the tourism product or action characteristics as well as the aim and public objective of the action. They were then reviewed and re-configurated using academic literature when possible to provide exclusive definitions and avoid results discrepancy (see Table 1 ).

Categories to classify the different tourism-related actions carried out by the cities. Source: Own authors (2021).

Some categories were easier to identify, such as Festivals, which have a lot of literature and are characterized by the time factor [ 59 ]. Pop-up events were separated from the festivals because they represent a single non-recurrent initiative [ 60 ], that requires another type of management and generates different impacts than a festival: it could be a concert, a book fair, a culinary event … As for the professional events; which include conferences, conventions, congresses, seminars, trade shows, business exhibitions, incentive events, or corporate/business meetings [ 61 ]; they represent the MICE sector, which is underrepresented in the literature on creative industries, intangible heritage, and tourism. Education refers to training programs, residencies, exchange programs, and workshops …, that is, activities that are not intended for professionals only, like the previous category, because they are in the learning area. Following Richards and Munsters [ 64 ], cultural tourism products and heritage types of equipment refer to creating a museum, interpretation centers, or library, as well as routes, itineraries, or maps. They are products consumed by cultural tourists. Finally, some actions were not identified in the previous categories because they were not described sufficiently in the report, as they are intended as a plan or a strategy, or because they are ongoing in a larger action. They were labeled as Initiatives. These heterogeneous actions are developed by city councils and stakeholders and could include various activities. In this sense, it could refer to a global project that is planned, to hubs in which they can mix cultural equipment with training education and other initiatives, or else to a political strategy. Nevertheless, since it is necessary to adopt a common definition under which to comprehend and categorize this vast variety of activities included in this category, we understand them as “Pilot projects, partnerships, and initiatives associating the public and private sectors, and civil society”, as one of the main areas of actions of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network according to UCCN mission statement reported by Guimarães et al. [ 2 ].

As in any classification exercise, these categories do not exist per se but serve our objective by separating the actions by their aim and public objective, which helps to understand how and to whom the cities direct their development strategies in their creative field.

4. Findings

The results are organized into two main sections. The first one presents the findings at a global and transversal level between all the creative fields, for the totality of the 321 actions that were extracted. In the second one, each creative field is detailed regarding the type of actions that are related to them.

From the 112 cities that published a report for the Creative Cities Network, 92 were identified as having written at least an action related to tourism. They are concentrated mainly in Europe, America, and East Asia. In the latter, almost all the reports include at least an action related to tourism.

Almost half of the cities which include tourism (42%) have only 1 or 2 actions related to tourism. Those who have 3 or 4 actions represent 30% of the total, almost the same proportion of the cities that wrote between 5 and 11 actions (28%). In fact, in the 4 cities that have published the greatest number of actions in tourism (between 9 and 11 actions), Japan is represented on 3 occasions and in 3 different creative fields: Sapporo (Media Arts), Tsuruoka (Gastronomy), and Sasayama (Crafts & Folk Art). The city of Linz, in Austria, is the one that has the greatest number of tourism-related actions (11) concentrated in Media Arts.

4.1. Types of action and their relation to the creative fields

The 112 reports are distributed in a balanced way between five creative fields that published between 22 and 18 reports each: Design (22), Literature (20), Crafts & Folk Art, Music and Gastronomy (18 reports each). The last two are Media Arts and Film, with 9 and 7 reports respectively.

However, the number of actions related to tourism is not proportional to the number of reports (see Fig. 1 ). The Crafts & Folk Art category, which was the 3rd regarding the number of reports (18), has published the greatest number of actions (73), representing almost 25% of the total. It is closely followed by Literature and Gastronomy (65 actions each). Film, which has the least number of reports, is also the last one with 12 actions. This could be explained by the fact that the actions related to this creative field are commonly linked to festivals or other activities that implicitly are directed to all public, visitors, or tourists. For a similar reason, tourism-related actions in the Music field are also particularly low, considering the number of monitoring reports published by those cities. For that, this result doesn't mean that the total of actions is low, but that these actions were not explicitly identified as related to a tourism strategy.

Number of identified tourism-related actions per creative field. Source: Own authors (2021).

As for the type of actions that were identified throughout the 112 reports (see Fig. 2 ), 159 have been categorized as Initiatives, representing half of the total actions. As described in the methodology section, this category englobes many types of actions that could not be positively categorized into another type, or that mix different strategies, like the hubs, or that represent projects and plans that act as umbrellas for different punctual and concrete actions. This is the case, for instance, of the Maruyama Village plan in Tamba Sasayama, which consists in renovating an old hamlet, creating new job opportunities, environment preservation, and creating a hub to dynamize the territory.

Number of identified tourism-related actions per category. Source: Own authors (2021).

Given the political nature of the reports, which justify the membership of the creative cities in the network, those actions related to strategies, plans, and policies are published as intentions to be carried out in the coming years, as well as demonstrating the goals that have already been achieved. For our analysis, these actions have been categorized as Initiatives. Examples of these are a) the promotion of a city as a tourism destination through the creation and improvement of its website, as in the case of Santa Fe, or b) the construction of buildings or the creation of new spaces to facilitate, introduce, and promote a creative industry as such in the city. These hubs, like the one built around the gastronomy creative field of Parma, are an example of those new spaces that cannot be considered classical heritage equipment and, thus, have been categorized as Initiatives.

Festival is the second most common type of action detected (55), the reason for that being that they can be associated with all of the creative fields. However, in general, they are not usually renowned events and their role in the promotion of the destination is not as relevant as it could be, since they are specialist festivals or events. Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment follows with 36 actions. They include products such as itineraries, maps, museums, or libraries, such as the Literary Walks in Krakow or the Italian Museum of Audio-visual and Cinema in Rome. Pop-up events and Education have 28 and 26 actions respectively. An example of the first could be the Island concerts series in Tongyeong, and as an example of Education , the ceramic apprenticeship program in Icheon, which is offered to local and international trainees, could be mentioned. Finally, Professional events, like the Krakow International Book Fair, have the lowest number of actions (17).

4.2. Tendencies by creative field

In this section, the distribution of action types by creative field will be explained. The order of the creative fields that are detailed will be from the one with the greatest number of actions to the least. As for the type of action, as stated before, Initiative is the one that is the most important. It is so in a transversal way, as it is the type of action that dominates each creative field. Therefore, the results will focus on the other action types. A general quantitative overview can be seen in the following table (see Table 2 ).

Quantitative results of tourism-related actions per creative field. Source: Own authors (2021).

Firstly, as said before, Craft & Folk Arts is the creative field with the highest number of identified actions related to the tourism sector. In this field, the actions related to Festival (15), Pop-Up Event (9), and Education (9) stand out as having more actions than in the other creative fields. The case of Tamba Sasayama stands out since the city organized five different festivals during the period covered by its monitoring report (2015–2019). Only 2 Cultural tourism products and items of heritage equipment were detected in Jaipur; one consisted in organizing heritage walks during world tourism day and the second refers to a project of augmented reality to promote intangible and tangible local arts, crafts, and cuisine, by making them visible to visitors and locals. A potential explanation for these scarce findings in cultural tourism products could be the close relationship of this cultural and creative field to creative tourism, which focuses on offering experiences directly and, this way, it does not always need “classical” cultural tourism products such as routes or museums to be showcased in tourism contexts.

Within the Gastronomy field, the actions tagged as Initiatives have the highest number (35) out of all the creative fields. As was the case for the previous field, Festival follows (11). Some examples are the annual Bergen Food Festival, the Islands and Flavors festival in Belem, and the Phuket Chinese New Year and Old Phuket Town Festival. The 3rd position is shared between Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment and Pop-Up event (6). And, finally, Professional event has the least actions (2).

In third position, Literature is the field that offers the most Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment (15) among the creative fields, items such as walks or maps; this is the case of, for instance, Barcelona's or Ulyanovsk's Literary Maps, or the Writer's Museum in Edinburgh. Festival follows with 7 actions. It is also the creative field with the highest number of professional events (4), the reason for which is the considerable number of book fairs.

The creative field of Design also uses festivals (9) as a main tool for tourism purposes. Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment and Pop-up event follow with 5 of each, and finally Education activities with 2 examples. In this category, there is no Professional event. The Initiatives are focused on Placemaking strategies, as shown by the example of the pop-up park in Budapest, which generated tourist interest. A similar approach was taken by the Media arts field. For instance, an example of a Media arts initiative is the Playable City in Austin, whose main objective is to reuse the city's infrastructure through workshops, art, presentations, and other outdoor activities, with interactive strategies. Festival is, as in most of the creative fields, the second most used type (7), followed by Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment (4).

In the Music field, Festival is obviously also the leading category after Initiatives. An example of a festival in this creative category with a considerable impact on tourism is the Festival Panafricain de Musiques–Brazzaville. Pop-up events and Education activities follow (2 each) and Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment and Professional event are to be found last (1 each). In the end, Cinema has Festival and Cultural tourism products and heritage equipment as leading actions (3 each) after Initiatives. There are no actions related to Professional event and Pop-Up event. Therefore, the Cinema creative field corresponds to the least prolific field in generating tourism-related activities according to the reports analyzed.

5. Discussion

The result that most raises awareness of the touristic potential of the creative industries is the high percentage of activities (17% of a total of 1301 actions) related to tourism. The relevant presence of tourism-oriented actions within UNESCO Creative Cities’ strategies is following the transformation of cultural tourism and its progressive integration of new dimensions of culture beyond tangible attractions [ 6 , 7 ]. It also suggests that creative industries are already present in the tourism strategy for a relevant part of the cities in the UNESCO Creative Cities Network. This was an expected result since joining UNESCO Creative Cities Network may be comprehended as part of a major strategy to showcase a city as a cutting-edge territory for a particular creative industry.

Given the political dimension of the analyzed documents, findings also show that policymakers consider the urban creative atmosphere as playing a key role in increasing the attractiveness of destinations [ 46 ]. In this sense, the integration of the tourism dimension in creative cities allows the improvement of the destination by, for instance, the development of creative initiatives that build more appealing urban settings for tourists [ 24 ], as well as the creation of small-scale creative businesses, spaces, and services businesses that allow the interaction between locals, visitors, and producers [ 27 ]. Therefore, fostering the binomial of tourism and creative fields may also be considered part of building this city's branding, as Guimaraes et al. [ 2 ] state. If tangible heritage is still a dominating feature of a destination's image, many other sources or assets influence a destination's image, including autonomous sources that are not directly linked with tourism [ 65 ]. An analysis of the image of Barcelona as projected in its promotional videos shows that Gastronomy and Wine, as well as Intangible Heritage, are both part of the four features most represented in the videos, so they are relevant assets to expose [ 66 ]. However, the study deplores that creative industries, which are an important part of Barcelona's development strategy, are underrepresented in the destination image.

Nevertheless, results show some differences between the creative fields in developing their relationship with tourism. Some creative industries such as Crafts & Folk Art, Gastronomy, Literature and Design, have a more consolidated relationship with the tourism industry than the other ones. Nevertheless, all the creative fields show relevant examples of developing a tourism offer based on creative industries. This shows that creative industries may be part of strategies to increase the tourism competitiveness of urban destinations [ 3 , 23 ].

Promoting tourism with creative industries permits destinations to develop a unique tourism offer [ 29 ], since it is closely linked to the local and “real” activity, actively giving substance to the destination identity. Following Stasiak's [ 29 ] thoughts, basing the development of the tourism offer on the local creative substrate may also be seen as a strategy to create more authentic tourism experiences. That is because the creation of tourism products must showcase what is happening within the destination and not staging or “faking” an image based on stereotypes.

Results also show that spatiality is vital in developing a tourism offer based on creative industries, as Carvalho et al. [ 24 ] fields of application in creative tourism demonstrate. For instance, our findings show that, on the one hand, giving visibility to creative industries through different events that may attract local and international visitors is present in most destinations analyzed. Moreover, on the other hand, raising awareness of urban places with a semantic relationship with creative industries through maps and routes appears within the practices of the analyzed destinations, which confirms the potential of relating creative industries with the development of tourism products.

To this aim, the experience in developing tourism products based on intangible cultural heritage and creative industries may be particularly fruitful. Indeed, our findings confirm that creating cultural spaces to showcase the relevance of a creative industry within a destination and developing itineraries are strategies already being used by UNESCO Creative Cities to develop tourism experiences. As Mendes et al. [ 50 ] state, this is relevant for appealing to a non-specialist visitor who is not visiting the destination based on its relationship with a creative field but may consider discovering the creative city through this kind of tourism product. Besides, it is also relevant to identify possible collaborations between different creative areas; for instance, given the close relationship between literature and film [ 40 ], the possibilities of cooperation within the framework of a particular festival, or developing some other tourism products that have yet to be tried. Besides, the presented cases in this analysis may also be considered a benchmarking contribution that facilitates the exploration of initiatives not yet explored.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed how UNESCO Creative Cities integrate a tourism perspective into their creative city strategy. It has explored the variety of actions developed by UNESCO Creative Cities that present an explicit interest in tourism, and that allow making tangible the potential close relationship between creative industries and the tourism sector. For this purpose, a descriptive analysis has been carried out through a content analysis of the most recent monitoring reports of UNESCO Creative Cities. This analysis has identified and categorized the different actions developed by those cities with a tourism approach. This has allowed the highlighting of common practices by which to integrate a creative atmosphere with the tourism industry.

Considering this context, the segmentation of the findings by their creative dimension aims to be a relevant information source for public policy-makers, as well as local businesses that plan to generate a tourist offering built upon the creative industry of the destination. This paper expects to facilitate the identification of possible actions to develop the creative environment of each destination. For instance, beyond festivals, creative dimensions such as Crafts & Folk Art or Gastronomy also can develop cultural tourism products such as routes and visits to local producers to create a non-temporary tourism offer. Nevertheless, it is necessary to integrate the development of tourism products based on creative industries in destination strategic plans and foster the implication of creative industries stakeholders in tourism activity. In this sense, it would be necessary to proceed with a further analysis of the different initiatives carried out by the UNESCO Creative Cities members to identify best practices as, for instance, the diffusion of business opportunities developed by the Edinburgh Tourism Action Group [ 67 ] in relation with the Edinburgh UNESCO City of Literature.

The present study presents different limitations. First, the sample has been built considering UNESCO Creative Cities Network and for this reason, some relevant cities were excluded from this analysis. Second, the research has been limited to only one creative field per city, the one by which they joined UNESCO's network. Some cities have interesting and innovative tourism projects and actions that were excluded if not written in the report because they are unrelated to their creative field. Finally, further research would be needed to perform an in-depth analysis of the particular actions developed under the wide Initiatives category, complementing the content analysis developed in the present article with other qualitative techniques.

Nevertheless, our results allow us to draw general trends. For instance, cities mainly base their initiatives on the fostering of synergies between creative industries and tourism via two different activities, i.e., festivals and tourism products such as routes. At the same time, the cities that adopt a considerable number of tourism initiatives are still scarce. Therefore, there is still room to grow and explore innovative and active ways to develop attractive spaces and experiences for tourists based on creative industries and intangible heritage. In this sense, another value of the presented analysis lies in the fact that it demonstrates the potential of binding tourism and the creative industries together and also permits the identification of interesting case studies to explore and identify innovative strategies in terms of products, governance, or promotion. At the same time, this analysis has focused on only one creative field per city, since UNESCO's Creative Cities join the network in just one creative field. Therefore, an interesting future research line could be to explore how the different creative fields interact and collaborate with the destination, as well as how this collaboration is promoted by the city council or other agents.

Author contribution statement

Jordi Arcos-Pumarola; Alexandra Georgescu Paquin: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Marta Hernández Sitges: Performed the experiments.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Declaration of interest's statement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, luxury tourism and hospitality employees: their role in service delivery.

The Emerald Handbook of Luxury Management for Hospitality and Tourism

ISBN : 978-1-83982-901-7 , eISBN : 978-1-83982-900-0

Publication date: 25 January 2022

Delivering services that create memorable luxury accommodation experiences rely on frontline staff to engage guests on a sensory level rather than merely a functional one. This engagement includes cognitive, emotional, relational and behavioural. Hospitality and tourism industries are people-orientated – people are needed to serve people in order to create desired experiences – and it is very difficult to create satisfaction or to revisit intention in every interaction that takes place. It is this intangible characteristic of the industries, provisions and tangible cues that play an important part in enhancing the overall luxury accommodation experience. Guests are very clear as to what they expect from luxury accommodation experiences: they feel that they are paying for a service that should be personalised, and that staff should realise what they want and need. The human interaction component and the co-creation that occurs between staff and guests is an essential dimension of the industry. The influence of these interactions on guest experiences and the delivery of services will be explored in this chapter.

- Frontline staff

- Luxury accommodation experience

- Co-creation

- Hospitality

Harkison, T. (2022), "Luxury Tourism and Hospitality Employees: Their Role in Service Delivery", Kotur, A.S. and Dixit, S.K. (Ed.) The Emerald Handbook of Luxury Management for Hospitality and Tourism , Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 199-219. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83982-900-020211010

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022 by Emerald Publishing Limited

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

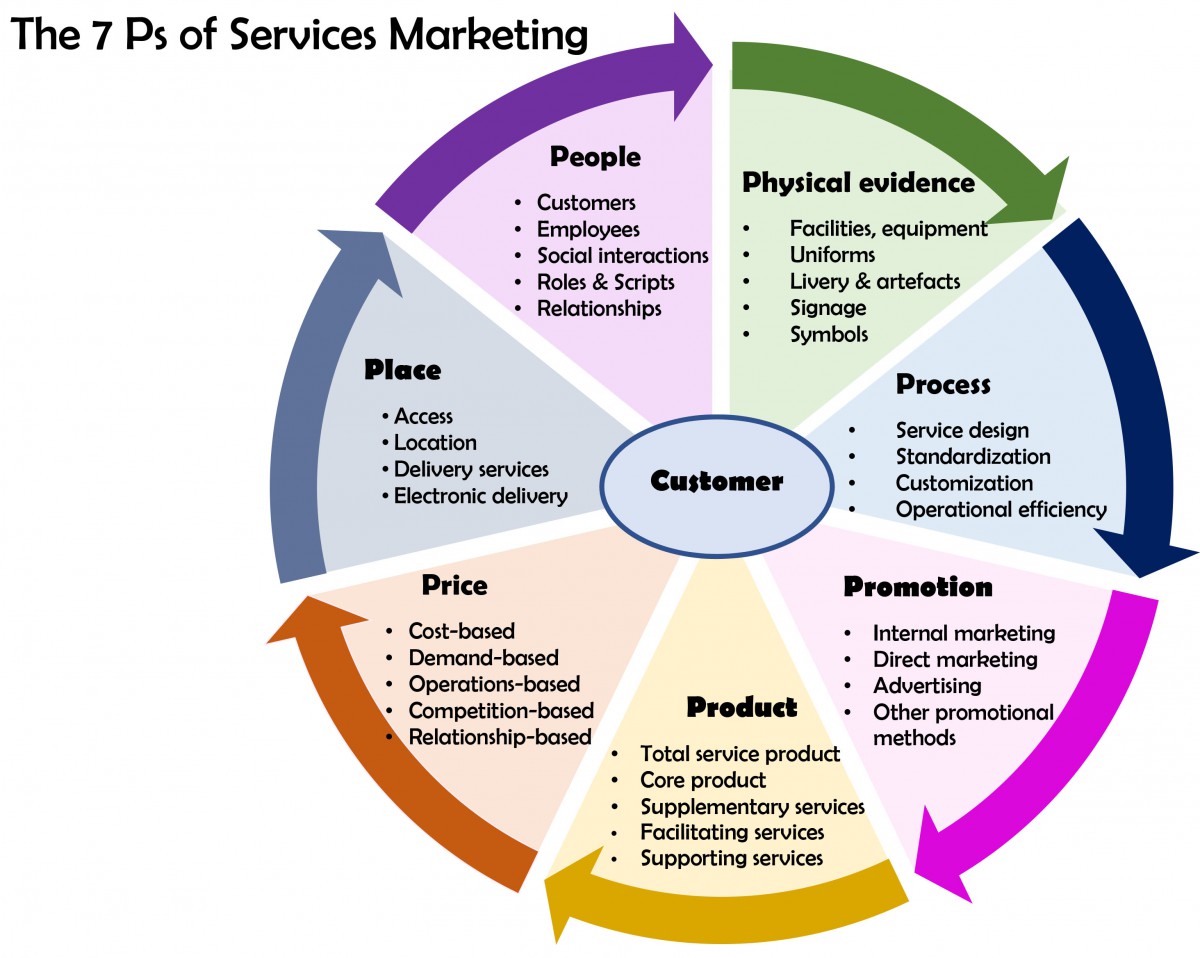

Marketing Tourism and Hospitality pp 33–61 Cite as

Characteristics of Tourism and Hospitality Marketing

- Richard George 2

- First Online: 09 May 2021

3262 Accesses

This chapter explores the characteristics of tourism and hospitality marketing. It begins with a discussion of the difference between services marketing and manufacturing marketing. The chapter then reviews the characteristics that make the marketing of these services different from the marketing of other products. These include intangibility, inseparability, variability, and perishability. Further, this chapter looks at the various marketing management strategies for tourism and hospitality businesses. It examines some of the marketing approaches, such as the to address the unique challenges facing the marketer. Finally, the characteristics of tourism and hospitality marketing are applied to low cost carrier Wizz Air.

- Intangibility, Inseparability, Variability

- Perishability

- Extended marketing mix, Services marketing triangle

- Service encounter

- Seasonality

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Booms, B., & Bitner, M. (1981). Marketing strategies and organisation structures for service firms. In J. Donnelly & W. George (Eds.), Marketing of services (p. 48). Chicago: AMA Proceedings Series.

Google Scholar

Bateson, J. E. G. (1995). Managing services marketing (4th ed.). London: Dryden Press.

Bitner, M. J. (1992). The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56 (2), 57–71.

Article Google Scholar

Bitner, M. J. (1995). Building service relationships: It’s all about the promise. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (4), 246–251.

Bughin, J., Doogan, J. & Vetvik. O.J. (2010). A new way to measure word of mouth marketing . Retrieved from: http://www.mckinseyquarterly.com/A_new_way_to_measure_word-of-mouth_marketing_2567 . (4 Mar 2014).

Bull, A. (1995). The economics of travel and tourism (2nd ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Longman.

Dobruszkes, F. (2006). An analysis of European low-cost airlines and their networks. Journal of Transport Geography, 14 (4), 249–264.

Godin, S. (2008). Purple cow . London: Penguin.

Hoffman, K. D., Bateson, J. E. G., Wood, E. H., & Kenyon, A. K. (2017). Services marketing: Concepts, strategies and cases (5th ed.). London: South-Western.

Judd, R. C. (1964). The case for refining services. Journal of Marketing , January,, 58–59.

Kotler, P., Bowen, J., Makens, J., & Baloglu, S. (2017). Marketing for hospitality and tourism (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Levitt, T. (1960). Marketing myopia. Harvard Business Review , July/August,, 45–56.

López, M., & Sicilia, M. (2014). Determinants of E-WOM influence: The role of consumers’ internet experience. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 9 (1), 28–43.

Lumsdon, L. (1997). Tourism marketing . London: International Thomson Press.

Meidan, A. (1989). Pricing in tourism . New York: Prentice-Hall.

Morrison, A. M. (2010). Hospitality and travel marketing (4th ed.). New York: Delmar Publishers.

Murphy, P., & Pritchard, M. (1997). Destination price-value perceptions: An examination of origin and seasonal influences. Journal of Travel Research, 35 (3), 16–22.

Payne, A., McDonald, M., & Frow, P. (2011). Marketing plans for services: A complete guide (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Rathmell, J. M. (1974). Marketing in the service sector . Cambridge, MA: Winthrop.

Traupel, L. (2017). Marketing to today’s distracted consumer . Retrieved from http://www.marcommwise.com/article.phtml?id=517 . (14 Apr 2017).

Wizz Air. (2019). Information and service [Online]. Available: https://wizzair.com/en-gb/information-and-services/about-us/company-information# . Accessed 13 June 2019.

Zeithaml, V., Bitner, M., & Gremler, D. (2017). Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Zwan, J. van der. (2006). Low Cost Carriers - Europa . Thesis at Utrecht University, Human Geography and Planning.

Further Reading

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

ICON College of Technology and Management/Falmouth University, London, UK

Richard George

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

1 Electronic Supplementary Material

(PPTX 404 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

George, R. (2021). Characteristics of Tourism and Hospitality Marketing. In: Marketing Tourism and Hospitality. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64111-5_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64111-5_2

Published : 09 May 2021

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-64110-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-64111-5

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

View prices for your travel dates

- Excellent 18

- Very Good 9

- All languages ( 43 )

- Russian ( 37 )

- English ( 4 )

- German ( 1 )

- Italian ( 1 )

" DIR: West; bigger nice evening sun but louder due to main street DIR:East; Quiter, very bright in the morning if sun rises "

Own or manage this property? Claim your listing for free to respond to reviews, update your profile and much more.

APELSIN HOTEL - Reviews (Elektrostal, Russia)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS