Get to know this special place we call home. Explore our Official Hawaiʻi Statewide Visitors' Guide.

Opportunities to mālama maui.

We share this list of opportunities for you to kōkua in ways that are meaningful to you.

Humble Beginnings Much has changed about the Hawaiʻi visitor industry since May 14, 1902, when W. C. Weedon convinced a group of Honolulu businessmen to pay him to advertise the Territory of Hawaiʻi on the Mainland. But one thing has stayed the same: Throughout the years, the entities which have promoted Hawaiʻi to the world have also had to promote themselves to Hawaiʻi. Despite the grumbling of powerful sugar planters, it was under the auspices of the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchants Association that the business of tourism promotion began. Weedon's proposal was to collect $100 per month for six months of lecture tours, and a 'magic lantern' show. Pictures, then as now, could tell Hawaiʻi's story better than anything except the recounted memories of people who had been here. Armed with his stereopticon and some tinted scenes of Hawaiʻi, Weedon boarded the ship for San Francisco with "a realistic and truthful representation of those remarkable people and beautiful lands of Hawaiʻi." There had been some precedence for tourism promotion in 1892, in the Hawaiʻi Bureau of Information. That effort fizzled, but when Hawaiʻi became a territory, it drew adventuresome travelers in a tourism boom around the turn of the century. Hotels blossomed, including Waikīkī's oldest surviving hostelry, the Moana Hotel, in 1901. Then, according to published accounts, the tourists stopped coming--possibly because Honolulu was swept by bubonic plague in 1899 and 1900. There were reports that Los Angeles was anticipating a bumper crop of tourists for the winter of 1902. Competition had already begun. The plan was to persuade California visitors to go "a little farther" when they were out West, and see Hawaiʻi, too. The time was right! Due, in great part to the writings of men like Mark Twain and Robert Louis Stevenson, Weedon drew packed houses on the West Coast, and soon wrote back to the merchants: "At every point I go, I find people ready and eager to learn more of Hawaiʻi." He urged them to provide, "some literature which may bear upon the advantages of our islands for rest and pleasure seekers..." Hawaiʻi had nothing to send, but efforts were already underway to launch systematic tourism advertising. On July 19, 1902, the Merchants Association proposed a permanent tourism promotion bureau. By 1903 a source of funding had been secured--a share of the voluntary tonnage tax shippers levied after the plague to rat-proof the docks and later to create a public health emergency fund and to promote business. That same year, the first Territorial Legislature debated tourism promotion for the first time--and rejected the Joint Tourist Committee's request for $10,000. Then Governor Sanford Dole backed the chamber's plea for reconsideration and $15,000 was approved for what became the Hawaiʻi Promotion Committee. Before the year was out, the new Alexander Young Hotel opened downtown, with the new tourism office in it manned by Edward Boyd, and about 2,000 visitors came to enjoy Hawaiʻi's version of paradise, after advertisements promising perpetual spring and romance appeared in national magazines. An early vest-pocket map and guide described, Honolulu--What to See and How to See It. The guide, one of the promotional pieces distributed with the help of steamship and railway agencies, advised that if taxi fares seemed too high, visitors could collect a refund from the Tourist Bureau. Another early pamphlet contained a bit of pithy prose from a speech by a talented California newspaper columnist, Mark Twain, correspondent for the Sacramento Union. Hawaiʻi tourism promoters and others have used his lines time and again since then: "No alien land in all the world has any deep strong charm for me but that one; no other land could so longingly and beseechingly haunt me sleeping and waking..." Hawaiʻi, he wrote, is "the loveliest fleet of islands anchored in any ocean." Over the decades, promotional efforts grew and so did the number of tourists. The tourism promotion agency acquired another new name, the Hawaiʻi Tourist Bureau in 1919, a new executive secretary, George Armitage in 1920, and a new function of counting visitors (8,000) and rooms in 1921. The governor appointed four members to the bureau to represent all the major islands, and the agency had a vastly expanded budget ($100,000) in 1922. Colorful community events were staged, usually involving flowers and parades. Entertainment flourished to keep the visitors occupied. Wonderfully wacky hapa-haole music was performed to ukulele and steel guitar. The tourist hula show was born, and instantly became controversial. The missionary families still considered the hula to be immoral, but the tourists loved it. The Bureau took part in many promotional activities over the years, but the most enduring and successful was launched in 1935 as the radio program, Hawaiʻi Calls. Originated, produced and narrated by Webley Edwards, it was broadcast for nearly four decades to the Mainland, Canada and Australia every Saturday, usually from the Moana Hotel's lanai on Waikīkī Beach. Listeners grew up with the sounds of Hawaiʻi from that popular show and developed lifelong desires to see and hear the real thing. In 1941, a record year, in which 31,846 visitors arrived, World War II brought an abrupt end to tourism in Hawaiʻi. Three years later, the Chamber of Commerce began bringing it back to life with a Hawaiʻi Travel Bureau, which concerned itself with leaving a friendly Territorial impression on the servicemen who were soon to go home. In 1945, the Hawaiʻi Visitors Bureau was launched. Major Mark Egan was named secretary, and a whole new era of Hawaiʻi tourism promotion began. A group of businessmen borrowed $20,000 and launched Aloha Week in 1947 to boost tourism in the otherwise slow fall season. An important priority was to get the ocean liner Lurline back in the passenger business after her wartime duty. It cost Matson $19 million, but in the spring of 1948, with an exuberant welcome by some 150,000 people and an 80 vessel escort arranged by the HVB, she steamed into Honolulu Harbor to reclaim her title as "glamour girl of the Pacific." In 1948, American President Lines resumed plying the Pacific and scheduled air service was inaugurated to Hawaiʻi. A long maritime strike in 1949 cut Hawaiʻi tourism in half, to 25,000 visitors and the Legislature agreed to match private contributions to the tourism promotion budget. That made it a million-dollar proposition over two years: Advertising on the Mainland; transmitting and financing Hawaiʻi Calls; special displays; Mainland offices; movies; publicity; literature; guides; warrior markers; music and hula to greet arriving ships and planes, and an HVB flower lei for every visitor! Special people got special greetings. The Lurline herself got a steamship sized lei, 80 feet of orange crepe paper, during the 1948 reception. Actor Joe E. Brown (and his invisible rabbit co-star) came to play in Harvey in 1950 and was greeted by the HVB with a lei of carrots. In 1953, the HVB held a pretty face contest and selected hula dancer Mae Beimes as the first official HVB Poster Girl. Her sweet smile and proffered plumeria lei adorned a poster that is still a part of Hawaiʻi history. Beimes was succeeded later by Beverly Rivera Noa, and Rose Marie Alvaro, a dancer who posed for four posters, and followed by Liz Logue, Tracy Monsarrat and Zoe Ann Roach, they became Hawaiʻi's best known representatives around the world. Statehood in 1959 brought with it the arrival of the first jet service to Honolulu. Tourism exploded. Waikīkī began to build up (and up). Sheer numbers eroded some of the personal touch like a lei greeting for every arriving visitor. But the Bureau hit the road. Hawaiian entertainers and promotion experts circled the globe to spread the Island word. The HVB metamorphosed again in 1961, when it began doing business under contract to the State Department of Planning and Economic Development. Private contributions had slacked off--industry leaders were spending more on their own advertising--while government funding increased. The 50-50 funding became two-thirds state, and one-third private financing of HVB efforts. In the mid 1960's, for the first time, advertisements circulated at home in Hawaiʻi pointing out the benefits of tourism to the community. At the same time other Pacific Rim nations were sending emissaries to the HVB to get the experts' advice and training on how to set up a tourism bureau. They included Australia, Canada, Tahiti, Fiji, Samoa, Taiwan, Korea and Alaska. The HVB diversified to include a Meetings & Conventions department, and later a Visitor Services department. Steadily during the 60's, 70's, and 80's the millions of tourists added up, and the HVB and Hawaiʻi learned to cope with the problems of success. The yearly tourism total reached nearly seven million people in 1990. 1991 was the breakpoint year for Hawaiʻi's visitor industry. The Gulf War raised fuel prices, detoured aircraft and decreased lift capacity to the Islands. Coupled with a downturn in both the U.S. and Japan economies, a drying up in overseas capital investment, and a reticence among eastbound visitors to come to the U.S. amidst threats of terrorism, arrivals and airline seats decreased through 1994. During 1995 & 1996, the organization was shifted from a community/government model to a business model emphasizing public/private partnerships. The organization became leaner, more flexible and proactive. New goals, performance standards and accountability measures were established. New initiatives were conceived, but programs were still hindered by a budget that would never allow Hawaiʻi to compete effectively with other destinations' investments. The Japanese market grew steadily for the next three years, reaching its highest visitor count in 1997. But, the U.S. Mainland market was still relatively stagnant during this time. In July 1996, the name was officially changed to the Hawaiʻi Visitors and Convention Bureau, to reflect a new emphasis on business/meeting travel and a new responsibility for marketing the world class, state-of-the-art Hawaiʻi Convention Center. The $350 million Center officially opened in June 1998 and represented the first significant tourism-related construction in over five years. The nature of tourism promotion changed to keep pace with the rest of the world. The advertising programs that had sold Hawaiʻi with pretty girls and palm trees began to stress the Islands' diversity, its Hawaiian culture and history, and the wide range of sports, activities, and cuisine. We began to appeal to a wider base of travelers who wanted more of what Hawaiʻi really is. While the competition has intensified, Hawaiʻi remained one of the world's most desired destinations. Unsurpassed natural beauty, pristine physical environment, and diversity of islands, combined with our world-famous spirit of "aloha", continue to be an unbeatable product. Some things don't change all that much! What did change were management, vision and politics. By 1997, it was obvious to everyone, from the Governor and Legislature to the man on the street that if we wanted to compete on a global scale, Hawaiʻi needed to stimulate structural & foundational changes. As James Michener once said, "Nothing that ever prospered on these islands ever did so without a struggle." The Governor convened the "ECONOMIC REVITALIZATION TASK FORCE (ERTF)." This unique coalition of community and government, counties and businesses established several key initiatives. For tourism, Hawaiʻi's number one economic driver and the catalyst for many inter-related industries, a special Tourism Bill was passed by the 1998 Legislature. It established the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority (HTA) with dedicated funding at a more globally competitive level. Its purpose is to create a strategic vision and direction for tourism and implement the key initiatives for sustainable, social and economic benefits for all of the Islands of Hawaiʻi. By 1999, dedicated funding was a reality and the HVCB was ready for the "new economy" challenges and opportunities. Our marketing mission is to create sustainable, diversified, global, leisure and business travel demand for all of these Islands of Aloha. The Bureau is uniquely qualified to serve the people of Hawaiʻi as a publicly supported, private corporation whose singular goal is to showcase and celebrate Hawaiʻi's diversity and aloha to the world; to encourage people to reawaken their senses and rejuvenate their spirit in Hawaiʻi; and to return again and again. HVCB is a vanguard organization. It is dedicated to creating a new 'Gold Standard' for destination marketing, and its primary product is the world's most-desired destination. Hawaiʻi, The Islands of Aloha.

Departments & Roles

- Contact Us |

- Privacy Policy |

- Terms & Conditions |

- Accessibility Statement |

We recognize the use of linguistic markings of the (modern) Hawaiian language including the ʻokina [‘] or glottal stop and the kahakō [ō] or macron (e.g., in place names of Hawaiʻi such as Lānaʻi). We acknowledge that individual businesses listed on this site may not use the ʻokina or kahakō , but we recognize the importance of using these markings to preserve the indigenous language and culture of Hawaiʻi and use them in all other forms of communications.

Copyright © 2024 Hawaiʻi Visitors & Convention Bureau. All Rights Reserved.

We serve cookies to analyze traffic and customize content on this site.

By clicking ACCEPT, you agree to the use of cookies.

Creating “Paradise of the Pacific”: How Tourism Began in Hawaii

- February 6, 2015

- James Mak , Economy , Working Papers

Recent Posts

UHERO’s Justin Tyndall cited in the 2024 Economic Report of the President

Delinquencies have spiked in the aftermath of the Maui wildfires

UHERO’s Byron Gangnes to be featured at HEA webinar

The Gender Pay Gap in Hawaii

Why are Condominiums so Expensive in Hawai‘i?

This article recounts the early years of one of the most successful tourist destinations in the world, Hawaii, from about 1870 to 1940. Tourism began in Hawaii when faster and more predictable steamships replaced sailing vessels in trans-Pacific travel. Governments (international, national, and local) were influential in shaping the way Hawaii tourism developed, from government mail subsidies to steamship companies, local funding for tourism promotion, and America’s protective legislation on domestic shipping. Hawaii also reaped a windfall from its location at the crossroads of the major trade routes in the Pacific region. The article concludes with policy lessons.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don't subscribe All new comments Replies to my comments Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

- Do not bully, intimidate, or harass any user.

- Do not post content that is hateful, threatening or wildly off-topic; or do anything unlawful, malicious, discriminatory or defamatory.

- Observe confidentiality laws at all times.

- Do not post spam or advertisements.

- Observe fair use, copyright and disclosure laws.

- Do not use vulgar language or profanity.

UHERO may amend this policy from time to time.

- 2424 Maile Way, Saunders Hall 540, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822

- [email protected]

- (808) 956-2325

- Department of Economics

- Social Science Research Institute

- College of Social Sciences

- Send me an update when UHERO posts new content

- Send me a monthly digest of UHERO content

Travel Guide

- Things to Do

- Things to See

- Planning a Trip

- A Cultural Primer

- Food & Drink

- Life & Language

- Recommended Books, Films & Music

- Active Pursuits

- Suggested Itineraries

- A Nature Guide

History in Hawaii

The First Hawaiians

Throughout the Middle Ages, while Western sailors clung to the edges of continents for fear of falling off the earth’s edge, Polynesian voyagers crisscrossed the planet’s largest ocean. The first people to colonize Hawaii were unsurpassed navigators. Using the stars, birds, and currents as guides, they sailed double-hulled canoes across thousands of miles, zeroing in on tiny islands in the center of the Pacific. They packed their vessels with food, plants, medicine, tools, and animals: everything necessary for building a new life on a distant shore. Over a span of 800 years, the great Polynesian migration connected a vast triangle of islands stretching from New Zealand to Hawaii to Easter Island and encompassing the many diverse archipelagos in between. Archaeologists surmise that Hawaii’s first wave of settlers came via the Marquesas Islands sometime after A.D. 1000, though oral histories suggest a much earlier date.

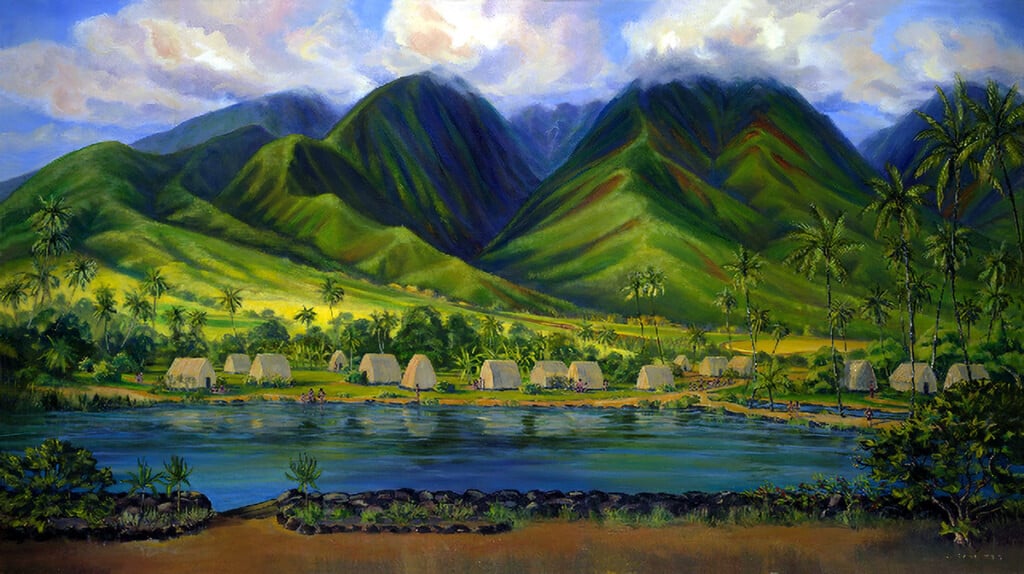

Over the ensuing centuries, a distinctly Hawaiian culture arose. Sailors became farmers and fishermen. These early Hawaiians were as skilled on land as they had been at sea; they built highly productive fish ponds, aqueducts to irrigate terraced kalo loi (taro patches), and 3-acre heiau (temples) with 50-foot-high rock walls. Farmers cultivated more than 400 varieties of kalo , their staple food; 300 types of sweet potato; and 40 different bananas. Each variety served a different need—some were drought resistant, others medicinal, and others good for babies. Hawaiian women fashioned intricately patterned kapa (barkcloth)—some of the finest in all of Polynesia. Each of the Hawaiian Islands was its own kingdom, governed by ali‘i (high-ranking chiefs) who drew their authority from an established caste system and kapu (taboos). Those who broke the kapu could be sacrificed.

The ancient Hawaiian creation chant, the Kumulipō , depicts a universe that began when heat and light emerged out of darkness, followed by the first life form: a coral polyp. The 2,000-line epic poem is a grand genealogy, describing how all species are interrelated, from gently waving seaweeds to mighty human warriors. It is the basis for the Hawaiian concept of kuleana , a word that simultaneously refers to privilege and responsibility. To this day, Native Hawaiians view the care of their natural resources as a filial duty and honor.

Western Contact

Cook’s Ill-Fated Voyage

In the dawn hours of January 18, 1778, Captain James Cook of the HMS Resolution spotted an unfamiliar set of islands, which he later named for his benefactor, the Earl of Sandwich. The 50-year-old sea captain was already famous in Britain for “discovering” much of the South Pacific. Now on his third great voyage of exploration, Cook had set sail from Tahiti northward across uncharted waters. He was searching for the mythical Northwest Passage that was said to link the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. On his way, he stumbled upon Hawaii (aka the Sandwich Isles) quite by chance.

With the arrival of the Resolution , Stone Age Hawaii entered the age of iron. Sailors swapped nails and munitions for fresh water, pigs, and the affections of Hawaiian women. Tragically, the foreigners brought with them a terrible cargo: syphilis, measles, and other diseases that decimated the Hawaiian people. Captain Cook estimated the native population at 400,000 in 1778. (Later historians claim it could have been as high as 900,000.) By the time Christian missionaries arrived 40 years later, the number of Native Hawaiians had plummeted to just 150,000.

In a skirmish over a stolen boat, Cook was killed by a blow to the head. His British countrymen sailed home, leaving Hawaii forever altered. The islands were now on the sea charts, and traders on the fur route between Canada and China stopped here to get fresh water. More trade—and more disastrous liaisons—ensued.

Two more sea captains left indelible marks on the islands. The first was American John Kendrick, who in 1791 filled his ship with fragrant Hawaiian sandalwood and sailed to China. By 1825, Hawaii’s sandalwood groves were gone. The second was Englishman George Vancouver, who in 1793 left behind cows and sheep, which ventured out to graze in the islands’ native forest and hastened the spread of invasive species. King Kamehameha I sent for cowboys from Mexico and Spain to round up the wild livestock, thus beginning the islands’ paniolo (cowboy) tradition.

King Kamehameha I was an ambitious ali‘i who used western guns to unite the islands under single rule. After his death in 1819, the tightly woven Hawaiian society began to unravel. One of his successors, Queen Kaahumanu, abolished the kapu system, opening the door for religion of another form.

Staying to Do Well

In April 1820, missionaries bent on converting Hawaiians arrived from New England. The newcomers clothed the natives, banned them from dancing the hula, and nearly dismantled the ancient culture. The churchgoers tried to keep sailors and whalers out of the bawdy houses, where whiskey flowed and the virtue of native women was never safe. To their credit, the missionaries created a 12-letter alphabet for the Hawaiian language, taught reading and writing, started a printing press, and began recording the islands’ history, which until that time had been preserved solely in memorized chants.

Children of the missionaries became business leaders and politicians. They married Hawaiians and stayed on in the islands, causing one wag to remark that the missionaries “came to do good and stayed to do well.” In 1848, King Kamehameha III enacted the Great Mahele (division). Intended to guarantee Native Hawaiians rights to their land, it ultimately enabled foreigners to take ownership of vast tracts of land. Within two generations, more than 80% of all private land was in haole (foreign) hands. Businessmen planted acre after acre of sugarcane and imported waves of immigrants to work the fields: Chinese starting in 1852, Japanese in 1885, and Portuguese in 1878.

King David Kalakaua was elected to the throne in 1874. This popular “Merrie Monarch” built Iolani Palace in 1882, threw extravagant parties, and lifted the prohibitions on hula and other native arts. For this, he was much loved. He proclaimed, “hula is the language of the heart and, therefore, the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people.” He also gave Pearl Harbor to the United States; it became the westernmost bastion of the U.S. Navy. While visiting chilly San Francisco in 1891, King Kalakaua caught a cold and died in the royal suite of the Sheraton Palace. His sister, Queen Liliuokalani, assumed the throne.

The Overthrow

For years, a group of American sugar plantation owners and missionary descendants had been machinating against the monarchy. On January 17, 1893, with the support of the U.S. minister to Hawaii and the Marines, the conspirators imprisoned Queen Liliuokalani in her own palace. To avoid bloodshed, she abdicated the throne, trusting that the United States government would right the wrong. As the Queen waited in vain, she penned the sorrowful lyric “Aloha Oe,” Hawaii’s song of farewell.

U.S. President Grover Cleveland’s attempt to restore the monarchy was thwarted by Congress. Sanford Dole, a powerful sugar plantation owner, appointed himself president of the newly declared Republic of Hawaii. His fellow sugarcane planters, known as the Big Five, controlled banking, shipping, hardware, and every other facet of economic life in the Islands. In 1898, through annexation, Hawaii became an American territory ruled by Dole.

Oahu’s central Ewa Plain soon filled with row crops. The Dole family planted pineapple on its sprawling acreage. Planters imported more contract laborers from Puerto Rico (1900), Korea (1903), and the Philippines (1907–31). Many of the new immigrants stayed on to establish families and become a part of the islands. Meanwhile, Native Hawaiians became a landless minority. Their language was banned in schools and their cultural practices devalued.

For nearly a century in Hawaii, sugar was king, generously subsidized by the U.S. government. Sugar is a thirsty crop, and plantation owners oversaw the construction of flumes and aqueducts that channeled mountain streams down to parched plains, where waving fields of cane soon grew. The waters that once fed taro patches dried up. The sugar planters dominated the territory’s economy, shaped its social fabric, and kept the islands in a colonial plantation era with bosses and field hands. But the workers eventually went on strike for higher wages and improved working conditions, and the planters found themselves unable to compete with cheap third-world labor costs.

Tourism Takes Hold

Tourism in Hawaii began in the 1860s. Kilauea volcano was one of the world’s prime attractions for adventure travelers. In 1865 a grass structure known as Volcano House was built on the rim of Halemaumau Crater to shelter visitors; it was Hawaii’s first hotel. The visitor industry blossomed as the plantation era peaked and waned.

In 1901 W. C. Peacock built the elegant Beaux Arts Moana Hotel on Waikiki Beach, and W. C. Weedon convinced Honolulu businessmen to bankroll his plan to advertise Hawaii in San Francisco. Armed with a stereopticon and tinted photos of Waikiki, Weedon sailed off in 1902 for 6 months of lecture tours to introduce “those remarkable people and the beautiful lands of Hawaii.” He drew packed houses. A tourism promotion bureau was formed in 1903, and about 2,000 visitors came to Hawaii that year.

The steamship was Hawaii’s tourism lifeline. It took 4 1/2 days to sail from San Francisco to Honolulu. Streamers, leis, and pomp welcomed each Matson liner at downtown’s Aloha Tower. Well-heeled visitors brought trunks, servants, and Rolls-Royces and stayed for months. Hawaiians amused visitors with personal tours, floral parades, and hula shows.

Beginning in 1935 and running for the next 40 years, Webley Edwards’s weekly live radio show, “Hawaii Calls,” planted the sounds of Waikiki—surf, sliding steel guitar, sweet Hawaiian harmonies, drumbeats—in the hearts of millions of listeners in the United States, Australia, and Canada.

By 1936, visitors could fly to Honolulu from San Francisco on the Hawaii Clipper , a seven-passenger Pan American Martin M-130 flying boat, for $360 one-way. The flight took 21 hours, 33 minutes. Modern tourism was born, with five flying boats providing daily service. The 1941 visitor count was a brisk 31,846 through December 6.

World War II & Statehood

On December 7, 1941, Japanese Zeros came out of the rising sun to bomb American warships based at Pearl Harbor. This was the “day of infamy” that plunged the United States into World War II.

The attack brought immediate changes to the islands. Martial law was declared, stripping the Big Five cartel of its absolute power in a single day. German and Japanese Americans were interned. Hawaii was “blacked out” at night, Waikiki Beach was strung with barbed wire, and Aloha Tower was painted in camouflage. Only young men bound for the Pacific came to Hawaii during the war years. Many came back to graves in a cemetery called Punchbowl.

The postwar years saw the beginnings of Hawaii’s faux culture. The authentic traditions had long been suppressed, and into the void flowed a consumable brand of aloha. Harry Yee invented the Blue Hawaii cocktail and dropped in a tiny Japanese parasol. Vic Bergeron created the mai tai, a drink made of rum and fresh lime juice, and opened Trader Vic’s, America’s first themed restaurant that featured the art, decor, and food of Polynesia. Arthur Godfrey picked up a ukulele and began singing hapa-haole tunes on early TV shows. In 1955, Henry J. Kaiser built the Hilton Hawaiian Village, and the 11-story high-rise Princess Kaiulani Hotel opened on a site where the real princess once played. Hawaii greeted 109,000 visitors that year.

In 1959, Hawaii became the 50th state of the United States. That year also saw the arrival of the first jet airliners, which brought 250,000 tourists to the state. By the 1980s, Hawaii’s visitor count surpassed 6 million. Fantasy megaresorts bloomed on the neighbor islands like giant artificial flowers, swelling the luxury market with ever-swankier accommodations. Hawaii’s tourist industry—the bastion of the state’s economy—has survived worldwide recessions, airline-industry hiccups, and increased competition from overseas. Year after year, the Hawaiian Islands continue to be ranked among the top visitor destinations in the world.

Who Is Hawaiian in Hawaii?

Only kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) are truly Hawaiian. The sugar and pineapple plantations brought so many different people to Hawaii that the state is now a remarkable potpourri of ethnic groups: Native Hawaiians were joined by Caucasians, Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Portuguese, Puerto Ricans, Samoans, Tongans, Tahitians, and other Asian and Pacific Islanders. Add to that a sprinkling of Vietnamese, Canadians, African Americans, American Indians, South Americans, and Europeans of every stripe. Many people retained the traditions of their homeland and many more blended their cultures into something new. That is the genesis of Hawaiian Pidgin, local cuisine, and holidays and celebrations unique to these Islands.

Speaking Hawaiian

Nearly everyone in Hawaii speaks English, though many people now also speak ōlelo Hawaii , the native language of these islands. Most roads, towns, and beaches possess vowel-heavy Hawaiian names, so it will serve you well to practice pronunciation before venturing out to ‘Aiea or Nu‘uanu.

The Hawaiian alphabet has only 12 letters: 7 consonants ( h, k, l, m, n, p, and w ) and 5 vowels ( a, e, i, o, and u )—but those vowels are liberally used! Usually they are “short,” pronounced: ah, ay, ee, oh, and oo. For example, wahine (woman) is wah-hee-nay . Most vowels are pronounced separately, but on occasion they are sounded together with the “long” pronunciation: ay, ee, eye, oh, and you . For example, Wai‘anae on Oahu’s leeward coast is Why-ah-ny .

Two pronunciation marks can help you sound your way through Hawaiian names. The okina, a backwards apostrophe, indicates a glottal stop or a slight pause. The kahakō is a line over a vowel indicating stress. Observing these rules, you can tell that Pā‘ia, a popular surf town on Maui’s North Shore, is pronounced PAH-ee-ah . The Likelike Highway is lee-KAY-lee-KAY .

Incorporate aloha (hello, goodbye, love) and mahalo (thank you) into your vocabulary. If you’ve just arrived, you’re a malihini (newcomer). Someone who’s been here a long time is a kama‘āina (child of the land). When you finish a job or your meal, you are pau (finished). On Friday, it’s pau hana , work finished. You eat pūpū (appetizers) when you go pau hana . Note: Hawaiian punctuation marks are not included in this edition, but you will see them on road signs, menus, and publications throughout Hawaii.

Note : This information was accurate when it was published, but can change without notice. Please be sure to confirm all rates and details directly with the companies in question before planning your trip.

- All Regions

- Australia & South Pacific

- Caribbean & Atlantic

- Central & South America

- Middle East & Africa

- North America

- Washington, D.C.

- San Francisco

- New York City

- Los Angeles

- Arts & Culture

- Beach & Water Sports

- Local Experiences

- Food & Drink

- Outdoor & Adventure

- National Parks

- Winter Sports

- Travelers with Disabilities

- Family & Kids

- All Slideshows

- Hotel Deals

- Car Rentals

- Flight Alerts

- Credit Cards & Loyalty Points

- Cruise News

- Entry Requirements & Customs

- Car, Bus, Rail News

- Money & Fees

- Health, Insurance, Security

- Packing & Luggage

- -Arthur Frommer Online

- -Passportable

- Road Trip Guides

- Alaska Made Easy

- Great Vacation Ideas in the U.S.A.

- Best of the Caribbean

- Best of Mexico

- Cruise Inspiration

- Best Places to Go 2024

University of Hawai'i Press

Developing a Dream Destination: Tourism and Tourism Policy Planning in Hawaii

Additional information.

- About the Book

Developing a Dream Destination is an interpretive history of tourism and tourism policy development in Hawai‘i from the 1960s to the twenty-first century. Part 1 looks at the many changes in tourism since statehood (1959) and tourism’s imprint on Hawai‘i. Part 2 reviews the development of public policy toward tourism, beginning with a story of the planning process that started around 1970—a full decade before the first comprehensive State Tourism Plan was crafted and implemented. It also examines state government policies and actions taken relative to the taxation of tourism, tourism promotion, convention center development and financing, the environment, Honolulu County’s efforts to improve Waikiki, and how the Neighbor Islands have coped with explosive tourism growth. Along the way, author James Mak offers interpretations of what has worked, what has not, and why. He concludes with a chapter on the lessons learned while developing a dream destination over the past half century.

- About the Author(s)

James Mak, Author

- Supporting Resources

- On Sale (Web orders only)

- Latest Catalogs

- New Releases

- Forthcoming Books

- Books in Series

- Publishing Partners

- Journals A-Z

- Our History

- Our Mission

- What We Publish

- Desk and Exam Copy Policy

- Hawai‘i Bookstores

- Online Resources

- Press Policies

- Employment Opportunities

- News and Events

- Customer Service

- Author Guidelines

- Journals: Subscriptions

- Rights and Permissions

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Email the Press

- Join our Distribution

- Write a Review

- East West Export Books

- Join Our List

- Privacy Overview

- Cookie Policy

University of Hawaiʻi Press Privacy Policy

What information do we collect.

University of Hawaiʻi Press collects the information that you provide when you register on our site, place an order, subscribe to our newsletter, or fill out a form. When ordering or registering on our site, as appropriate, you may be asked to enter your: name, e-mail address, mailing 0address, phone number or credit card information. You may, however, visit our site anonymously. Website log files collect information on all requests for pages and files on this website's web servers. Log files do not capture personal information but do capture the user's IP address, which is automatically recognized by our web servers. This information is used to ensure our website is operating properly, to uncover or investigate any errors, and is deleted within 72 hours. University of Hawaiʻi Press will make no attempt to track or identify individual users, except where there is a reasonable suspicion that unauthorized access to systems is being attempted. In the case of all users, we reserve the right to attempt to identify and track any individual who is reasonably suspected of trying to gain unauthorized access to computer systems or resources operating as part of our web services. As a condition of use of this site, all users must give permission for University of Hawaiʻi Press to use its access logs to attempt to track users who are reasonably suspected of gaining, or attempting to gain, unauthorized access.

WHAT DO WE USE YOUR INFORMATION FOR?

Any of the information we collect from you may be used in one of the following ways:

To process transactions

Your information, whether public or private, will not be sold, exchanged, transferred, or given to any other company for any reason whatsoever, without your consent, other than for the express purpose of delivering the purchased product or service requested. Order information will be retained for six months to allow us to research if there is a problem with an order. If you wish to receive a copy of this data or request its deletion prior to six months contact Cindy Yen at [email protected].

To administer a contest, promotion, survey or other site feature

Your information, whether public or private, will not be sold, exchanged, transferred, or given to any other company for any reason whatsoever, without your consent, other than for the express purpose of delivering the service requested. Your information will only be kept until the survey, contest, or other feature ends. If you wish to receive a copy of this data or request its deletion prior completion, contact [email protected].

To send periodic emails

The email address you provide for order processing, may be used to send you information and updates pertaining to your order, in addition to receiving occasional company news, updates, related product or service information, etc. Note: We keep your email information on file if you opt into our email newsletter. If at any time you would like to unsubscribe from receiving future emails, we include detailed unsubscribe instructions at the bottom of each email.

To send catalogs and other marketing material

The physical address you provide by filling out our contact form and requesting a catalog or joining our physical mailing list may be used to send you information and updates on the Press. We keep your address information on file if you opt into receiving our catalogs. You may opt out of this at any time by contacting [email protected].

HOW DO WE PROTECT YOUR INFORMATION?

We implement a variety of security measures to maintain the safety of your personal information when you place an order or enter, submit, or access your personal information. We offer the use of a secure server. All supplied sensitive/credit information is transmitted via Secure Socket Layer (SSL) technology and then encrypted into our payment gateway providers database only to be accessible by those authorized with special access rights to such systems, and are required to keep the information confidential. After a transaction, your private information (credit cards, social security numbers, financials, etc.) will not be stored on our servers. Some services on this website require us to collect personal information from you. To comply with Data Protection Regulations, we have a duty to tell you how we store the information we collect and how it is used. Any information you do submit will be stored securely and will never be passed on or sold to any third party. You should be aware, however, that access to web pages will generally create log entries in the systems of your ISP or network service provider. These entities may be in a position to identify the client computer equipment used to access a page. Such monitoring would be done by the provider of network services and is beyond the responsibility or control of University of Hawaiʻi Press.

DO WE USE COOKIES?

Yes. Cookies are small files that a site or its service provider transfers to your computer’s hard drive through your web browser (if you click to allow cookies to be set) that enables the sites or service providers systems to recognize your browser and capture and remember certain information. We use cookies to help us remember and process the items in your shopping cart. You can see a full list of the cookies we set on our cookie policy page. These cookies are only set once you’ve opted in through our cookie consent widget.

DO WE DISCLOSE ANY INFORMATION TO OUTSIDE PARTIES?

We do not sell, trade, or otherwise transfer your personally identifiable information to third parties other than to those trusted third parties who assist us in operating our website, conducting our business, or servicing you, so long as those parties agree to keep this information confidential. We may also release your personally identifiable information to those persons to whom disclosure is required to comply with the law, enforce our site policies, or protect ours or others’ rights, property, or safety. However, non-personally identifiable visitor information may be provided to other parties for marketing, advertising, or other uses.

CALIFORNIA ONLINE PRIVACY PROTECTION ACT COMPLIANCE

Because we value your privacy we have taken the necessary precautions to be in compliance with the California Online Privacy Protection Act. We therefore will not distribute your personal information to outside parties without your consent.

CHILDRENS ONLINE PRIVACY PROTECTION ACT COMPLIANCE

We are in compliance with the requirements of COPPA (Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act), we do not collect any information from anyone under 13 years of age. Our website, products and services are all directed to people who are at least 13 years old or older.

ONLINE PRIVACY POLICY ONLY

This online privacy policy applies only to information collected through our website and not to information collected offline.

YOUR CONSENT

By using our site, you consent to our web site privacy policy.

CHANGES TO OUR PRIVACY POLICY

If we decide to change our privacy policy, we will post those changes on this page, and update the Privacy Policy modification date. This policy is effective as of May 25th, 2018.

CONTACTING US

If there are any questions regarding this privacy policy you may contact us using the information below. University of Hawaiʻi Press 2840 Kolowalu Street Honolulu, HI 96822 USA [email protected] Ph (808) 956-8255, Toll-free: 1-(888)-UH-PRESS Fax (800) 650-7811

More information about our Cookie Policy

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in History

- History by Period

- Regional and National History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Browse content in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Browse content in Religion

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- Asian Studies

- Browse content in Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Migration Studies

- Race and Ethnicity

- Reviews and Awards

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Developing a Dream Destination: Tourism and Tourism Policy Planning in Hawaii

- Cite Icon Cite

This is an interpretive history of tourism and tourism policy development in Hawaii from the 1960s to the twenty-first century. Part 1 looks at the many changes in tourism since statehood (1959) and tourism’s imprint on Hawaii. Part 2 reviews the development of public policy toward tourism, beginning with a story of the planning process that started around 1970—a full decade before the first comprehensive State Tourism Plan was crafted and implemented. It also examines state government policies and actions taken relative to the taxation of tourism, tourism promotion, convention center development and financing, the environment, Honolulu County’s efforts to improve Waikiki, and how the Neighbor Islands have coped with explosive tourism growth. Along the way, the book offers interpretations of what has worked, what has not, and why. It concludes with a chapter on the lessons learned while developing a dream destination over the past half century.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Hawaii Hotels

The history of tourism in hawaii.

Hawaii, the 50th state of the United States, has a rich history of tourism that dates back to the 19th century. The Hawaiian Islands, located in the Pacific Ocean, have long been a popular destination for American tourists looking for a tropical escape. From the early days of American expansionism to the present-day global travel industry, Hawaii has been a hub of tourism activity.

Early Origins of American Tourists in Hawaii

Hawaii first became a popular tourist destination in the late 1800s, when American sailors and business people began to travel to the islands for work and leisure. These early tourists were drawn to Hawaii’s warm weather, lush landscapes, and exotic culture. The first luxury hotel in Hawaii, the Moana Hotel, was built in 1901 on the island of Oahu. This hotel helped to establish Hawaii as a tourist destination and set the stage for the growth of the tourism industry in the islands.

The Growth of Tourism in Oahu

Oahu, the third-largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, has been the center of tourism activity in Hawaii since the early days of American tourism. The island is home to the state capital, Honolulu, and is the hub of business and cultural activity in the state. Oahu’s popularity as a tourist destination has been driven by its warm weather, beautiful beaches, and rich history.

In the early 20th century, Oahu became a popular destination for American soldiers and sailors, who were drawn to the island’s exotic culture and warm climate. The growth of the military presence in Hawaii during World War II helped to further establish the island as a popular tourist destination. After the war, the island became a popular destination for American tourists, who were drawn to its warm weather, beautiful beaches, and rich cultural heritage.

The Growth of Tourism in the Other Hawaiian Islands

While Oahu has been the center of tourism activity in Hawaii, the other Hawaiian islands have also seen significant growth in tourism in recent decades. The island of Maui, in particular, has become a popular destination for tourists, who are drawn to its beautiful beaches, lush landscapes, and rich cultural heritage.

Maui is home to several luxury hotels , including the Grand Wailea , the Four Seasons Resort Maui , and the Ritz Carlton Kapalua . These hotels offer guests access to some of the most beautiful beaches in the world, as well as opportunities for outdoor recreation and cultural exploration.

The island of Kauai, known as the “Garden Isle,” is another popular destination for tourists. Kauai is home to several luxury hotels, including the 1 Hotel Hanalei Bay, and the Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort and Spa. These hotels offer guests access to some of the most beautiful beaches and lush landscapes in the world.

The Island of Hawaii

The island of Hawaii, also known as the “Big Island,” has become a popular destination for tourists in recent years. The island is home to several luxury hotels, including the Four Seasons Resort Hualalai and the Mauna Kea Beach Hotel. These hotels offer guests access to some of the most beautiful beaches and lush landscapes in the world, as well as opportunities for outdoor recreation and cultural exploration.

Tourism has had a profound impact on the Hawaiian Islands, bringing economic growth and cultural preservation to the state. Over the years, the industry has created jobs, supported local businesses, and showcased the rich cultural heritage of the islands.

The Hawaiian Islands are a popular destination for millions of tourists from around the world, who are drawn to its warm weather, beautiful beaches, and rich cultural heritage. From Oahu to Maui, Kauai, and the Big Island, visitors are able to experience the unique beauty and diversity of the Hawaiian Islands.

While the tourism industry has faced criticism and controversy in recent years, it is important to recognize the positive impact it has had on the Hawaiian economy and culture. Through responsible tourism practices and sustainable development, the industry can continue to support local communities and preserve the rich heritage of the Hawaiian Islands for future generations to enjoy.

Thomas Magnum

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

I'm too dumb to figure out if my website uses cookies or not! But you should presume it probably does. It uses google analytics so I can tell if people read my content or not, but don't worry I can't tell who you are. I'm almost certain google probably have some clever method of tracking you that I don't really understand. It may involve a cookie. If you continue to use the site we're going to presume you're OK with that.

And, incase you haven't figured it out already if you book a hotel from clicking a link on this site I will earn a commission. If a lot of you book hotels then I'll become rich.

A Better Way to Visit Hawai‘i

How will hawai‘i—facing climate change, overtourism, and a push to reclaim native lands—welcome travelers again.

- Copy Link copied

Rethinking Hawai‘i

Brendan George Ko

In July, suddenly it seemed as if everyone I knew was traveling to, or had just returned from, Hawai‘i. Neighbors. Friends. Social media acquaintances. And they all came back saying a version of the same thing: I feel so rejuvenated. I needed that. I was so burnt out.

On the one hand, I was happy for them. It’s been a trying couple of years, and who doesn’t want to take a break in a beautiful place? On the other hand, I wondered about the choice to visit now—especially given the staggering number of post-pandemic travelers —and about the mindset with which they visited.

Not because I wanted to travel-shame, but because I was fresh off a month-long dive into the stories you’ll soon read. Stories that take you back to the day in 1893 when American businessmen staged a coup d’état and overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy, stories that take you into the fight for Hawaiian sovereignty, and stories that offer suggestions for new ways to visit more conscientiously.

The questions posed here might make you uncomfortable. In fact, I hope they do. They made me uncomfortable. While I consider myself a thoughtful traveler I’ve traveled to Hawai‘i many times without a full grasp of the history of sovereignty, colonialism, and the oppression of Native Hawaiians, and without giving much thought to who was profiting from my visit and who might be suffering because of it.

I aim to hold on to that discomfort for as long as possible. For we, mainland travelers, should no longer be at the center of the conversation about Hawai‘i. It’s time for us to cede our desire to treat the islands as an escape in order to hear from the people who have made that escape possible for so long.

In the digital age, it’s easy to just book a trip with a couple of clicks—flight, hotels, restaurant reservations—but if we spend a bit more time reading, thinking, and educating ourselves, we can intentionally plan a trip that gives to the community just as much as it gives to us. —Aislyn Greene, deputy editor

Beyond Aloha: Hawai‘i Is Not Our Playground

“Have you sunbathed at Waikīkī Beach? Snorkeled at Shark’s Cove? If so, our route that morning [on O‘ahu] would have seemed confounding,” writes AFAR contributor Chris Colin in Hawai‘i Is Not Our Playground . “My guide Kajihiro drove us inland, away from the beaches and souvenir shops. Up a gentle hill we went, and at the top, he pulled over. We were pointed back down the hill now, looking at the most visited tourist destination in the whole state.

“As many as 4,000 people a day visit Ke Awalau o Pu‘uloa, the inlet shimmering faintly below us. Most of them know it by its newer name, Pearl Harbor. As I tried to picture warplanes roaring in, Kajihiro grabbed a worn binder from the backseat. Opening it up on his lap, he proceeded to walk me through all that had come before that moment in 1941, and all that had led to that moment—history omitted by the USS Arizona Memorial tour.”

Hawai‘i has been reinvented for the mainlander’s imagination, but its locals—facing historic overtourism and a crippling pandemic—are trying to change that.

>> Read the full story .

Hawaiian sovereignty, and what’s at stake

George Brendan Ko

In What Is the Hawai‘i Sovereignty Movement? a Hawaiian scholar explains the multifaceted movement asking the United States to return the lands taken during the 1893 coup d’état that overthrew the Hawaiian monarchy. “What’s at stake here is 1.75 million acres of land—close to half of the lands of the archipelago—and the right of the Hawai‘ian people to their own government,” says Dr. Jonathan Kay Kamakawiwo‘ole Osorio. “But the sovereignty movement is not one monolithic thing. We do not agree among ourselves about what form that sovereignty should take.”

Aloha ‘Āina: It’s “love for our lands,” roughly, but so much more

“There’s a sense of the deification of the land and elevating the land to something bigger than just the scientific sum total of its parts. Not thinking of, for instance, volcanoes in the ocean as purely some sort of natural phenomena, but deifying them in a way that gives them a certain amount of unknowability—and being comfortable with that unknowability. Looking at a space and recognizing that this is bigger than humans will ever be able to comprehend, and we have to give some reverence to that and see ourselves as people who are in a relationship with something bigger than us.” —Kawai Strong Washburn, a climate activist and the author of the novel Sharks in the Time of Saviors , which follows the struggles and triumphs of a Hawaiian family touched by the divine.

Cultural Traditions: The Revival of Traditional Voyaging

“The canoe I usually sail for is called Mo‘okiha O Pi‘ilani. It’s a 62-foot-long double-hull canoe. It typically fits anywhere from 10 to 16 people. When we sail, the wa‘a is the vessel for so many different spirits. There’s the kūpuna , the ancestors. And there’s everybody who put their mana , their spirit energy, into creating the canoe, because there isn’t a company that makes them—it’s communities that get together and sand [the wood] endlessly till your hands are soft or bleeding. The voyaging canoe has my blood on it.” —Brendan George Ko, photographer and author of the new book Moemoeā , and member of Maui’s Hui O Wa‘a Kaulua voyaging community.

A New Way to Visit: How to Better Connect With the Islands

“Our whole thing is about interaction. I would rather meet you and develop a relationship with you so that you can come to us and talk about your plans and what you want to do and how you can be a good visitor on our island. . . . Because the minute you step off the plane, you have a responsibility to the people of Hawai‘i to mindfully think about what you’re doing here, where you’re going, where you’re shopping. Hawai‘i is a special place. When you come, what is your intention?” —Lesley Texeira, is the cofounder of the Maui-based company Aloha Missions. She and cofounder Tamika Recopuerto help visitors better connect with—and give back to—the island.

Giving Back: One Way to Support Maui’s Natural Spaces

“The vision from my dad that I try to carry on is that people need to understand why these cultural resources—in this case the archaeology and the plants and the rocks—are important to maintain. You don’t know what secrets they hold that we haven’t discovered yet.” —Edwin “Ekolu” Lindsey, president of Maui Cultural Lands, an organization that invites travelers to help restore the island’s natural spaces.

Tourism in Hawaii

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Tourism in Hawaii is big business. But why is this industry so important and what does it all mean? Read on to find out…

Tourism in Hawaii

The geography of hawaii , the tourism industry in hawaii , statistics about tourism in hawaii , the most popular tourist attractions in hawaii , the most popular types of tourism in hawaii , the economic impacts of tourism in hawaii , the social impacts of tourism in hawaii , the environmental impacts of tourism in hawaii , faqs about tourism in hawaii, to conclude: tourism in hawaii.

Hawaii, an archipelago of unparalleled beauty in the central Pacific, stands as a testament to the harmonious blend of nature and culture. This article explores the intricacies of Hawaii’s tourism sector, discussing its profound impact on the state’s economy and its interplay with the islands’ rich heritage and traditions.

Hawaii is an archipelago located in the Pacific Ocean and is the only U.S. state composed entirely of islands. It is located about 2,400 miles southwest of California. Here is an overview of the geography of Hawaii:

1. Islands: The Hawaiian Islands consist of eight main islands: Hawaii (also known as the Big Island), Maui, Oahu, Kauai, Molokai, Lanai, Niihau, and Kahoolawe. Each island has its own unique geography and characteristics.

2. Volcanoes: Hawaii is famous for its volcanic activity, and it is home to some of the most active volcanoes in the world. The Big Island of Hawaii is dominated by five volcanoes, including Mauna Loa, the largest shield volcano on Earth, and Kilauea, one of the world’s most active volcanoes.

3. Mountains and Ranges: The islands of Hawaii feature dramatic mountain ranges and peaks. Mauna Kea, located on the Big Island, is the highest point in the state, rising to an elevation of 13,796 feet (4,205 metres) above sea level. Other prominent mountain ranges include the West Maui Mountains on Maui and the Koʻolau Range on Oahu.

4. Coastline: Hawaii has a diverse coastline with beautiful sandy beaches, rugged cliffs, and rocky shores. The islands are known for their stunning coastal landscapes, including iconic spots like the Na Pali Coast on Kauai and the Road to Hana on Maui.

5. Rainforests: The islands of Hawaii are home to lush rainforests that thrive in the tropical climate. These rainforests are characterised by dense vegetation, including a variety of endemic plant species, vibrant flowers, and cascading waterfalls.

6. Coral Reefs: Hawaii is surrounded by extensive coral reef ecosystems that support a diverse array of marine life. The reefs are popular for snorkelling and scuba diving, offering opportunities to explore colourful coral formations and encounter marine species like sea turtles and tropical fish.

7. Climate: Hawaii has a tropical climate, with warm temperatures throughout the year. The coastal areas experience mild temperatures, while higher elevations can be cooler. The islands also experience trade winds, which help keep the climate pleasant.

8. Agriculture: Agriculture plays a significant role in Hawaii’s economy and landscape. The islands are known for their agricultural products such as pineapples, macadamia nuts, coffee, and tropical fruits. You can find plantations and farms cultivating these crops across various islands.

9. National Parks: Hawaii is home to several national parks, including Hawaii Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island, Haleakala National Park on Maui, and Pu’uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park on the Big Island. These parks offer opportunities for outdoor recreation, scenic views, and cultural exploration.

10. Marine Life: Hawaii’s waters are teeming with diverse marine life. Whales, dolphins, sea turtles, and a wide variety of fish species can be found in the surrounding ocean. The islands are popular for activities such as whale watching, swimming with dolphins, and exploring marine sanctuaries.

The geography of Hawaii is incredibly diverse and offers a wide range of natural wonders and outdoor experiences. From volcanoes and rainforests to stunning coastlines and marine ecosystems, Hawaii is a paradise for nature enthusiasts and visitors seeking adventure and relaxation.

The tourism industry in Hawaii is a significant contributor to the state’s economy and plays a vital role in its overall development. Here is an overview of the tourism industry in Hawaii:

1. Economic Importance: Tourism is one of the primary industries in Hawaii, contributing significantly to the state’s economy. It generates billions of dollars in revenue each year, provides employment opportunities, and supports various sectors such as accommodations, food and beverage services, transportation, and retail.

2. Natural and Cultural Attractions: Hawaii’s natural beauty, including its stunning beaches, volcanic landscapes, lush rainforests, and diverse marine life, attracts visitors from around the world. The state also boasts a rich cultural heritage with its indigenous Hawaiian traditions, music, hula, and historical sites, which add to the tourism appeal.

3. Beaches and Water Activities: Hawaii’s world-renowned beaches are a major draw for tourists. Visitors come to enjoy activities such as swimming, snorkelling, surfing, paddleboarding, and sunbathing. The islands offer a variety of beach experiences, from bustling coastal areas to secluded and pristine stretches of sand.

4. Outdoor Recreation: Hawaii’s diverse geography provides ample opportunities for outdoor activities. Visitors can hike through lush valleys, explore volcanic craters, go ziplining, take helicopter tours, go whale watching (during the winter months), and participate in eco-tours to experience the islands’ natural wonders.

5. Cultural Tourism: Hawaii’s unique cultural heritage is an important aspect of its tourism industry. Visitors can engage in cultural activities such as attending luau celebrations, visiting cultural and historical sites, learning about traditional arts and crafts, and experiencing traditional Hawaiian music and dance performances.

6. Hospitality Industry: The hospitality sector in Hawaii is well-developed, offering a wide range of accommodations, including luxury resorts, hotels, vacation rentals, and bed and breakfasts. These establishments cater to various budgets and preferences, ensuring that tourists have options for their stay.

7. Cruise Tourism: Hawaii is a popular destination for cruise ships, with many major cruise lines offering itineraries that include the Hawaiian Islands. Cruise tourists can enjoy island hopping and experience multiple destinations during their trip.

8. Sustainable Tourism: Hawaii places a strong emphasis on sustainable tourism practices to protect its natural and cultural resources. Efforts are made to promote responsible tourism, conservation, and the preservation of the delicate ecosystems found across the islands.

9. Events and Festivals: Hawaii hosts numerous events and festivals throughout the year, attracting visitors with cultural celebrations, music festivals, sporting events, and more. Examples include the Merrie Monarch Festival (celebrating hula), the Honolulu Marathon, and the Hawaii Food and Wine Festival.

10. Economic Challenges: While tourism provides significant economic benefits, it also poses challenges. The industry’s heavy reliance on tourism revenue leaves the state vulnerable to fluctuations in the global economy, natural disasters, and external factors such as geopolitical events or travel restrictions.

Overall, tourism in Hawaii is a vital component of the state’s economy, offering visitors a chance to experience the unique natural beauty, rich culture, and warm hospitality that the islands have to offer. It continues to play a central role in shaping Hawaii’s identity as a premier tourist destination.

Now lets put things into perspective. Here are some statistics about tourism in Hawaii:

1. Visitor Arrivals: In 2019, Hawaii welcomed approximately 10.4 million visitors, comprising both domestic and international travellers.

2. Visitor Expenditures: Visitor spending in Hawaii totaled $17.75 billion in 2019, contributing significantly to the state’s economy.

3. Economic Impact: The tourism industry in Hawaii directly and indirectly supported over 200,000 jobs in 2019, accounting for a substantial portion of the state’s employment.

4. International Visitors: The majority of visitors to Hawaii come from the United States. However, international travellers, primarily from Japan, Canada, and Australia, also contribute significantly to the tourism market.

5. Visitor Origin: The main source markets for Hawaii’s international visitors are Japan, Canada, Australia, China, South Korea, and New Zealand.

6. Accommodation Statistics: In 2019, Hawaii had over 80,000 lodging units available, including hotels, resorts, vacation rentals, and bed and breakfast establishments.

7. Length of Stay: The average length of stay for visitors in Hawaii varies by market. In 2019, the average length of stay for international visitors was around nine days, while domestic visitors stayed for about seven days on average.

8. Popular Activities: Some of the most popular activities for tourists in Hawaii include visiting beaches, exploring natural attractions like volcanoes and waterfalls, snorkelling, surfing, attending cultural events and festivals, and enjoying outdoor activities such as hiking and zip-lining.

9. Cruise Ship Passengers: Hawaii is a favoured destination for cruise ships. In 2019, over 1.2 million cruise ship passengers visited the state.

10. Repeat Visitors: Hawaii has a high rate of repeat visitors, with many tourists returning to the islands multiple times. Repeat visitors contribute to the sustained popularity of Hawaii as a travel destination.

These statistics provide insights into the scale and significance of tourism in Hawaii, showcasing its economic impact, visitor demographics, popular activities, and the importance of both domestic and international markets.

Hawaii is renowned for its breathtaking natural beauty, diverse landscapes, and rich cultural heritage. Here are some of the most popular tourist attractions in Hawaii:

1. Pearl Harbor and USS Arizona Memorial (Oahu): This historic site honours the memory of those who lost their lives during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Visitors can explore the USS Arizona Memorial and the accompanying museum to learn about the events of December 7, 1941.

2. Waikiki Beach (Oahu): Located in Honolulu, Waikiki Beach is one of the most famous and iconic beaches in Hawaii. It offers golden sands, crystal-clear waters, and a vibrant atmosphere with numerous hotels, restaurants, and shopping opportunities.

3. Haleakala National Park (Maui): This national park is home to the Haleakala volcano, which offers stunning panoramic views from its summit. Visitors can go hiking, cycling, or simply witness the awe-inspiring sunrise or sunset from the summit.

4. Road to Hana (Maui): This scenic drive along the northeastern coast of Maui is famous for its breathtaking views of waterfalls, lush rainforests, and rugged coastal landscapes. The journey includes numerous stops at viewpoints, gardens, and natural attractions.

5. Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (Big Island): This park is home to two active volcanoes, Kilauea and Mauna Loa. Visitors can explore volcanic landscapes, walk through lava tubes, and witness the incredible power of nature.

6. Na Pali Coast (Kauai): The Na Pali Coast is renowned for its dramatic cliffs, emerald-green valleys, and pristine beaches. Visitors can hike along the Kalalau Trail, take a boat tour, or even view the coast from a helicopter.

7. Waimea Canyon (Kauai): Known as the “Grand Canyon of the Pacific,” Waimea Canyon offers breathtaking vistas with its colourful cliffs and lush vegetation. Hiking trails and scenic viewpoints provide opportunities for exploration and photography.

8. Akaka Falls State Park (Big Island): This park features the stunning 442-foot Akaka Falls, along with lush tropical vegetation and cascading streams. A short loop trail takes visitors through the rainforest, offering glimpses of other waterfalls as well.

9. Molokini Crater (Maui): A popular snorkelling and diving destination, Molokini Crater is a partially submerged volcanic crater that offers crystal-clear waters, vibrant coral reefs, and diverse marine life.

10. Polynesian Cultural Center (Oahu): Located in Laie, the Polynesian Cultural Center offers visitors a chance to experience the diverse Polynesian cultures through traditional performances, demonstrations, and exhibits.

These attractions showcase the natural wonders, historical sites, and cultural richness that make Hawaii such a popular tourist destination. However, Hawaii has much more to offer, and each island has its own unique attractions worth exploring.

Hawaii offers a diverse range of tourism experiences, catering to various interests and preferences. Here are some of the most popular types of tourism in Hawaii:

1. Beach Tourism: Hawaii is renowned for its stunning beaches with pristine sands and turquoise waters. Beach tourism is one of the primary attractions, offering opportunities for swimming, sunbathing, snorkelling, surfing, and other water activities.

2. Nature and Adventure Tourism: Hawaii’s natural landscapes provide ample opportunities for outdoor adventures. Visitors can hike through lush rainforests, explore volcanic craters, zipline across canyons, go horseback riding, and experience thrilling activities like helicopter tours and lava boat tours.

3. Cultural Tourism: Hawaii has a rich indigenous culture and a strong Polynesian heritage. Cultural tourism allows visitors to explore Hawaiian traditions, attend traditional ceremonies, participate in hula lessons, and learn about ancient Hawaiian arts and crafts.

4. Volcano Tourism: The active volcanoes in Hawaii, particularly Kilauea on the Big Island, attract visitors interested in experiencing the raw power of nature. Volcano tourism includes guided tours to volcanic sites, lava viewing, and educational exhibits at the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park.

5. Marine and Water Sports Tourism: Hawaii’s crystal-clear waters offer fantastic opportunities for water sports and marine activities. Snorkelling, scuba diving, kayaking, paddleboarding, sailing, and whale watching (during the winter months) are popular activities among tourists.

6. Golf Tourism: Hawaii is home to world-class golf courses, attracting golf enthusiasts from around the globe. The islands offer stunning views and challenging courses, making it an ideal destination for golf tourism.

7. Wellness and Spa Tourism: Hawaii’s tranquil and serene environment lends itself well to wellness and relaxation. Many resorts and spas offer luxurious treatments, yoga retreats, meditation sessions, and holistic wellness experiences.

8. Culinary Tourism: Hawaii’s cuisine is a blend of diverse influences, including traditional Hawaiian, Asian, and Polynesian flavours. Culinary tourism allows visitors to indulge in unique dishes, attend food festivals, explore local markets, and even take cooking classes to learn the art of Hawaiian cuisine.

9. Eco-Tourism: With its diverse ecosystems and commitment to conservation, Hawaii is a great destination for eco-tourism. Visitors can engage in sustainable activities such as hiking in nature reserves, wildlife spotting, exploring botanical gardens, and supporting eco-friendly initiatives.

10. Wedding and Honeymoon Tourism: Hawaii’s romantic ambiance, beautiful landscapes, and luxurious resorts make it a sought-after destination for weddings and honeymoons. Many couples choose Hawaii for its stunning beachfront ceremonies and unforgettable romantic experiences.

These types of tourism highlight the various attractions and experiences that draw visitors to Hawaii. Each island offers a unique blend of these tourism types, allowing travellers to tailor their experience based on their interests and desires.

The tourism industry in Hawaii has a significant economic impact on the state. Here are some key economic impacts of tourism in Hawaii:

1. Job Creation: Tourism in Hawaii is a major source of employment in Hawaii. The industry directly supports a wide range of jobs, including hotel and resort staff, restaurant and food service workers, tour guides, transportation providers, and retail employees. Additionally, there are indirect jobs created in industries that support tourism, such as construction, agriculture, and manufacturing.

2. Revenue Generation: Tourism in Hawaii generates substantial revenue for the state of Hawaii. Visitor expenditures, including accommodation, dining, transportation, shopping, and recreational activities, contribute to the local economy. This revenue helps fund public services, infrastructure development, and community projects.

3. Small Business Support: The tourism industry in Hawaii provides opportunities for small businesses to thrive. Local entrepreneurs can establish businesses such as boutique hotels, tour operators, restaurants, souvenir shops, and artisanal products, benefiting from the influx of visitors.

4. Tax Revenue: Tourism in Hawaii contributes to tax revenue in Hawaii. Visitor-related taxes, such as hotel room taxes, rental car taxes, and general excise taxes on tourism-related goods and services, help fund government programs, services, and public infrastructure.

5. Investment and Development: The tourism industry attracts investment and promotes development in Hawaii. Hotel and resort construction, renovation projects, infrastructure upgrades, and the expansion of tourism-related services create employment opportunities and stimulate economic growth.