Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

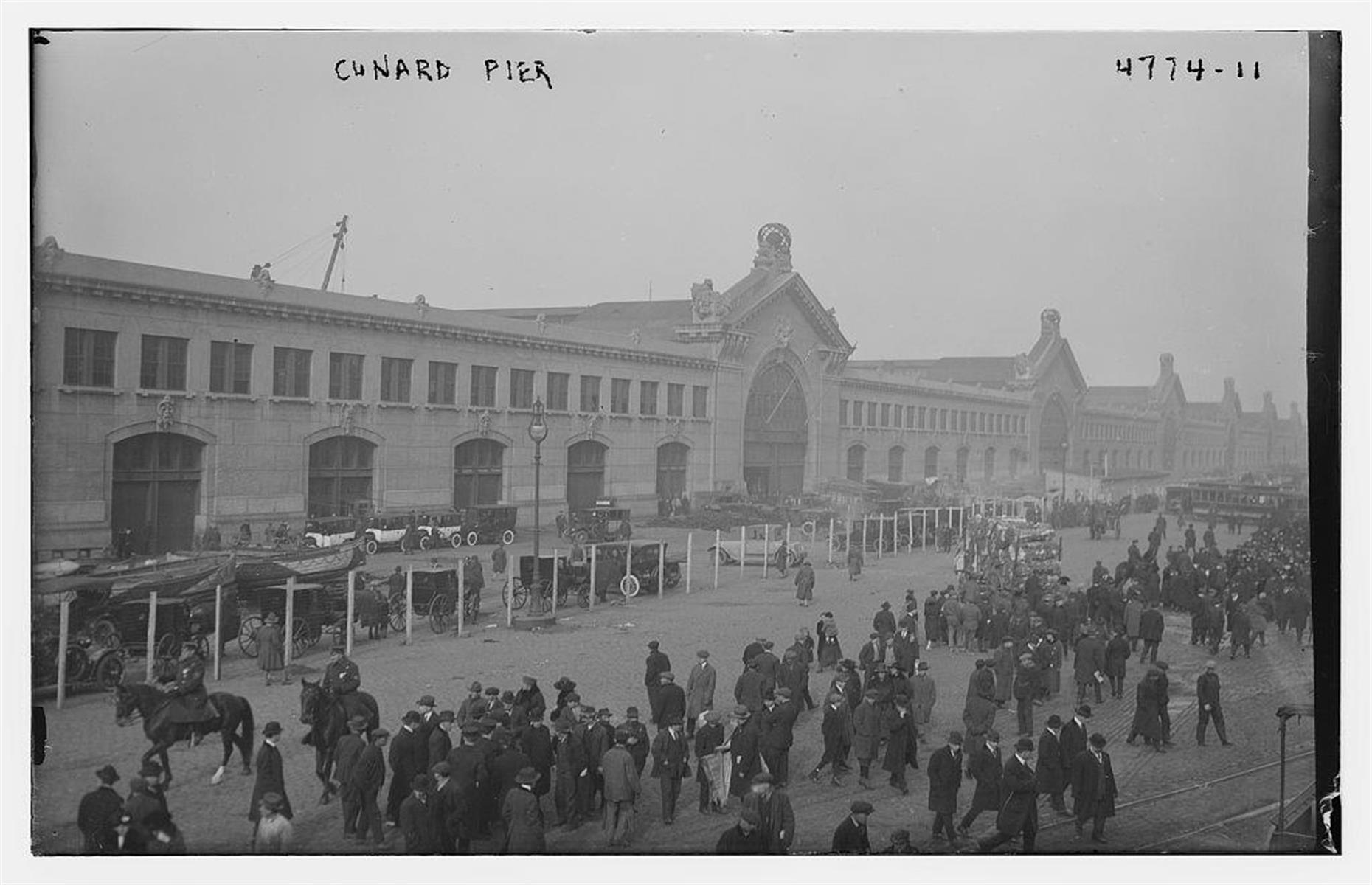

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

The World Cruise of the Great White Fleet: Honoring 100 Years of Global Partnerships and Security Hardcover – January 1, 1656

Under orders from President Theodore Roosevelt, sixteen battleships of the United States’ Atlantic Battle Fleet and their consorts made a peace-time circumnavigation of the globe, from December 1907 to February 1909. Text, illustrations, and captions tell the story of this fourteen-month world cruise. Separate chapters provide an overview of the origins, course, and accomplishments of the cruise, describe the ships that circumnavigated the globe, depict the character and experiences of the sailors who participated, narrate the cruise’s principal events and itinerary, and analyze the Great White Fleet’s significance organizationally for the United States Navy and diplomatically for the United States of America.

- Print length 106 pages

- Language English

- Publisher Naval Historical Center

- Publication date January 1, 1656

- Dimensions 11 x 0.75 x 9 inches

- ISBN-10 0945274599

- ISBN-13 978-0945274599

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Naval Historical Center; First Edition (January 1, 1656)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 106 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0945274599

- ISBN-13 : 978-0945274599

- Item Weight : 1.45 pounds

- Dimensions : 11 x 0.75 x 9 inches

- #9,099 in Naval Military History

- #167,474 in United States History (Books)

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top review from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The world cruise of the Great White Fleet : honoring 100 years of global partnerships and security

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

1,615 Views

7 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Unknown on November 26, 2012

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Circling the Globe: The Voyage of the Great White Fleet

- Battles & Wars

- Key Figures

- Arms & Weapons

- Naval Battles & Warships

- Aerial Battles & Aircraft

- French Revolution

- Vietnam War

- World War I

- World War II

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/khickman-5b6c7044c9e77c005075339c.jpg)

- M.A., History, University of Delaware

- M.S., Information and Library Science, Drexel University

- B.A., History and Political Science, Pennsylvania State University

The Great White Fleet refers to a large force of American battleships that circumnavigated the globe between December 16, 1907 and February 22, 1909. Conceived by President Theodore Roosevelt, the fleet's cruise was intended to demonstrate that the United States could project naval power anywhere in the world as well as to test the operational limits of the fleet's ships. Beginning on the the East Coast, the fleet circled South America, and visited the West Coast before transiting the Pacific for port calls in New Zealand, Australia, Japan, China, and the Philippines. The fleet returned home via the Indian Ocean, Suez Canal, and the Mediterranean.

A Rising Power

In the years after its triumph in the Spanish-American War , the United States quickly grew in power and prestige on the world stage. A newly established imperial power with possessions that included Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, it was felt that the United States needed to substantially increase its naval power to retain its new global status. Led by the energy of President Theodore Roosevelt, the US Navy built eleven new battleships between 1904 and 1907.

While this construction program greatly grew the fleet, the combat effectiveness of many of the ships was jeopardized in 1906 with the arrival of the all-big gun HMS Dreadnought . Despite this development, the expansion of naval strength was fortuitous as Japan, recently triumphant in the Russo-Japanese War after victories at Tsushima and Port Arthur, presented a growing threat in the Pacific.

Concerns with Japan

Relations with Japan were further stressed in 1906, by a series of laws which discriminated against Japanese immigrants in California. Touching off anti-American riots in Japan, these laws were ultimately repealed at Roosevelt's insistence. While this aided in calming the situation, relations remained strained and Roosevelt became concerned about the US Navy's lack of strength in the Pacific.

To impress upon the Japanese that the United States could shift its main battle fleet to the Pacific with ease, he began devising a world cruise of the nation's battleships. Roosevelt had effectively utilized naval demonstrations for political purposes in the past as earlier that year he had deployed eight battleships to the Mediterranean to make a statement during the Franco-German Algeciras Conference.

Support at Home

In addition to sending a message to the Japanese, Roosevelt wished to provide the American public with a clear understanding that the nation was prepared for a war at sea and sought to secure support for the construction of additional warships. From an operational standpoint, Roosevelt and naval leaders were eager to learn about the endurance of American battleships and how they would stand up during long voyages. Initially announcing that the fleet would be moving to the West Coast for training exercises, the battleships gathered at Hampton Roads in late 1907 to take part in the Jamestown Exposition .

Preparations

Planning for the proposed voyage required a full assessment of the US Navy's facilities on the West Coast as well as across the Pacific. The former were of particular importance as it was expected the fleet would require a full refit and overhaul after steaming around South America (the Panama Canal was not yet open). Concerns immediately arose that the only navy yard capable of servicing the fleet was at Bremerton, WA as the main channel into San Francisco's Mare Island Navy Yard was too shallow for battleships. This necessitated the re-opening of a civilian yard on Hunter's Point in San Francisco.

The US Navy also found that arrangements were needed to ensure that the fleet could be refueled during the voyage. Lacking a global network of coaling stations, provisions were made to have colliers meet the fleet at prearranged locations to permit refueling. Difficulties soon arose in contracting sufficient American-flagged ships and awkwardly, especially given the point of the cruise, the majority of the colliers employed were of British registry.

Around the World

Sailing under command of Rear Admiral Robley Evans, the fleet consisted of the battleships USS Kearsarge , USS Alabama , USS Illinois , USS Rhode Island , USS Maine , USS Missouri , USS Ohio , USS Virginia , USS Georgia , USS New Jersey , USS Louisiana , USS Connecticut , USS Kentucky , USS Vermont , USS Kansas , and USS Minnesota . These were supported by a Torpedo Flotilla of seven destroyers and five fleet auxiliaries. Departing the Chesapeake on December 16, 1907, the fleet steamed past the presidential yacht Mayflower as they left Hampton Roads.

Flying his flag from Connecticut , Evans announced that the fleet would be returning home via the Pacific and circumnavigating the globe. While it is unclear whether this information was leaked from the fleet or became public after the ships' arrival on the West Coast, it was not met with universal approval. While some were concerned that the nation's Atlantic naval defenses would be weakened by the fleet's prolonged absence, others were concerned about the cost. Senator Eugene Hale, the chairman of the Senate Naval Appropriation Committee, threatened to cut the fleet's funding.

To the Pacific

Responding in typical fashion, Roosevelt replied that he already had the money and dared Congressional leaders to "try and get it back." While the leaders wrangled in Washington, Evans and his fleet continued with their voyage. On December 23, 1907, they made their first port call at Trinidad before pressing on to Rio de Janeiro. En route, the men conducted the usual "Crossing the Line" ceremonies to initiate those sailors who had never crossed the Equator.

Arriving in Rio on January 12, 1908, the port call proved eventful as Evans suffered an attack of gout and several sailors became involved in a bar fight. Departing Rio, Evans steered for the Straits of Magellan and the Pacific. Entering the straits, the ships made a brief call at Punta Arenas before transiting the dangerous passage without incident.

Reaching Callao, Peru on February 20, the men enjoyed a nine-day celebration in honor of George Washington's birthday. Moving on, the fleet paused for one month at Magdalena Bay, Baja California for gunnery practice. With this complete, Evans moved up the West Coast making stops at San Diego, Los Angeles, Santa Cruz, Santa Barbara, Monterey, and San Francisco.

Across the Pacific

While in port at San Francisco, Evans' health continued to worsen and command of the fleet passed to Rear Admiral Charles Sperry. While the men were treated as royalty in San Francisco, some elements of the fleet traveled north to Washington, before the fleet reassembled on July 7. Before departing, Maine and Alabama were replaced by USS Nebraska and USS Wisconsin due to their high fuel consumption. In addition, the Torpedo Flotilla was detached. Steaming into the Pacific, Sperry took the fleet to Honolulu for a six-day stop before proceeding on to Auckland, New Zealand.

Entering port on August 9, the men were regaled with parties and warmly received. Pushing on to Australia, the fleet made stops at Sydney and Melbourne and was met with great acclaim. Steaming north, Sperry reached Manila on October 2, however liberty was not granted due to a cholera epidemic. Departing for Japan eight days later, the fleet endured a severe typhoon off Formosa before reaching Yokohama on October 18. Due to the diplomatic situation, Sperry limited liberty to those sailors with exemplary records with the goal of preventing any incidents.

Greeted with exceptional hospitality, Sperry and his officers were housed at the Emperor's Palace and the famed Imperial Hotel. In port for a week, the men of the fleet were treated to constant parties and celebrations, including one hosted by famed Admiral Togo Heihachiro . During the visit, no incidents occurred and the goal of bolstering good will between the two nations was achieved.

The Voyage Home

Dividing his fleet in two, Sperry departed Yokohama on October 25, with half heading for a visit to Amoy, China and the other to the Philippines for gunnery practice. After a brief call in Amoy, the detached ships sailed for Manila where they rejoined the fleet for maneuvers. Preparing to head for home, the Great White Fleet departed Manila on December 1 and made a week-long stop at Colombo, Ceylon before reaching the Suez Canal on January 3, 1909.

While coaling at Port Said, Sperry was alerted to a severe earthquake at Messina, Sicily. Dispatching Connecticut and Illinois to provide aid, the rest of the fleet divided to make calls around the Mediterranean. Regrouping on February 6, Sperry made final port call at Gibraltar before entering the Atlantic and setting a course for Hampton Roads.

Reaching home on February 22, the fleet was met by Roosevelt aboard Mayflower and cheering crowds ashore. Lasting fourteen months, the cruise aided in the conclusion of the Root-Takahira Agreement between the United States and Japan and demonstrated that modern battleships were capable of long journeys without significant mechanical breakdowns. In addition, the voyage led to several changes in ship design including the elimination of guns near the waterline, the removal of old-style fighting tops, as well as improvements to ventilation systems and crew housing.

Operationally, the voyage provided thorough sea training for both the officers and men and led to improvements in coal economy, formation steaming, and gunnery. As a final recommendation, Sperry suggested that the US Navy change the color of its ships from white to gray. While this had been advocated for some time, it was put into effect after the fleet's return.

- Spanish-American War: USS Oregon (BB-3)

- World War II: USS West Virginia (BB-48)

- Battleship USS Mississippi (BB-41) in World War II

- Great White Fleet: USS Ohio (BB-12)

- World War II: USS Idaho (BB-42)

- World War II: Admiral Thomas C. Kincaid

- Great White Fleet: USS Nebraska (BB-14)

- World War II: USS North Carolina (BB-55)

- Great White Fleet: USS Minnesota (BB-22)

- World War I/II: USS Arizona (BB-39)

- World War I/II: USS Texas (BB-35)

- The USS Iowa (BB-61) in World War II

- World War II: USS South Dakota (BB-57)

- World War II: USS New Jersey (BB-62)

- Vietnam War: USS Oriskany (CV-34)

- Korean War: USS Valley Forge (CV-45)

The Great White Fleet

After the Civil War, American sea power became a pitiful joke. Then an aroused nation set out to build a first-class, modern navy, and in 1907 proudly sent it off around the world

February 1964

The S.S. Virginius of New York, Captain Charles Fry, darted up from the Jamaica coast, bound for Cuba, which lay blue in the distance. It was November, 1873. As the ship crossed the brilliant Caribbean, the Spanish gunboat Tornado took chase and closed quickly. When the Spaniards boarded, they found the Virginius stacked high with arms for Cuba’s rebels, then engaged in another of their apparently endless insurrections against the mother country.

The captured ship was taken to Santiago, on Cuba’s southern shore. Forty-three of the passengers and crew were bound, lined up against a wall, and shot. The rest were saved only by the arrival of H.M.S. Niobe , whose captain insisted that the Spanish governor “stop that filthy slaughter.” For a time, war between the United States and Spain seemed unavoidable. President Grant ordered the fleet mobilized at Key West.

A marvelous collection of naval museum pieces gathered there. Eleven old wooden steam frigates and steam sloops, their decks lined with muzzle-loading smoothbores, their masts laden with canvas, made up the cruising force. Five iron monitors, hastily recommissioned, were towed down from the James and the Delaware, where they had been rusting since the Civil War. The fleet, which coidd maneuver only as fast as its slowest member, the steam sloop Shenandoah , puffed along at four and a half knots. (Spain had four modern seagoing ironclads which could make nearly three times that speed.) In the end, perhaps, it was well that the President turned the Virginius affair over to the State Department for settlement.

There were few who would have guessed that twentyfive years later an American fleet would litter the beaches of Cuba with the burned and blasted wrecks of Spanish warships; that another American squadron would do the same thing in the distant Philippines; or that a decade after those victories, the most powerful fleet of battleships ever to circumnavigate the world would fly American colors.

Two then-obscure young men were to play major roles in this transformation. One, the only midshipman ever to skip plebe year at Annapolis—who, ironically, was to write of his naval career, “I believe I should have done better elsewhere”—was in 1873 a quiet, austere, and unhappy officer in command of the U.S.S. Wasp , a captured Civil War blockade-runner performing odd jobs for the ramshackle fleet of the South Atlantic Station. The other was the asthmatic son of a wealthy New York City family, just back from a sojourn in Germany and preparing for a gentleman’s career at Harvard. Their names were Alfred Thayer Mahan and Theodore Roosevelt. It was Mahan whose writings on the role of sea power in history would one day have such a far-reaching influence both at home and abroad. And it was his enthusiastic supporter, Roosevelt, who, first as Assistant Secretary of the Navy and then as President, would put the theories of that officer-scholar into practice.

Meanwhile the nation soon forgot its Caribbean misadventure: there was much more urgent business at hand. The problems of Reconstruction, the surge of population toward the West, the burgeoning of new industries, the tips and downs of the stock market, labor troubles, the social upheavals of immigration, and the scandals of the Grant administration seemed to leave little time for overseas affairs—or for the needs of a neglected navy.

While the navies of the major European powers relied increasingly on armored ships driven by steam, the American Navy, which had pioneered in both fields and which had more recent battle experience than all the rest put together, cruised under sail, in wooden ships. (There was even a move afoot to make all navy captains pay out of their own pockets for whatever coal their ships burned.) The promotion process stagnated; an Annapolis graduate might still be a lieutenant at the age of fifty. To make matters worse, the office of Secretary of the Navy was filled throughout the 1870’s by political hacks. Grant’s appointee, George M. Robeson, apparently managed to feather his nest with some $320,000 of Navy Department funds; a few years later, Richard W. Thompson of Indiana, who served under Hayes, visited a warship and exclaimed with some amazement, “The damn thing is hollow!”

“By the year 1880 the navy had fallen to a pitifully low ebb,” noted Frank M. Bennett, the historian of the nineteenth-century American steam navy. “Repairs were no longer possible, for space for more patches was lacking upon almost every ship of ours then afloat.… A sense of humiliation dogged the American naval officer as he went about his duty in foreign lands; in the Far East, in the lesser countries along the Mediterranean Sea, and even in the sea ports of South America, people smiled patronizingly upon him and from a sense of politeness avoided speaking of naval subjects in his presence.” That year there were thirty-eight admirals on the active list (with commands afloat for but six) and only thirty-nine ships. It was a situation that openly invited ridicule. In an Oscar Wilde comedy written at the time, an American lady who despaired of her country because it had neither curiosities nor ruins was consoled with heavy irony because “you have your manners and your navy.”

But a change was in the air, though it would be a long time before the officers and men of our patchwork naval forces would have tangible evidence of it. In 1880, when James Garfield was elected President, he chose William Hunt, a New Orleans Republican, as Secretary of the Navy. Hunt had long been friendly with two famous heroes of the Civil War, Admirals David Farragut and David Dixon Porter, and he had a lively interest in the service. He ordered a board, headed by Rear Admiral John Rodgers, to find out what was needed to rejuvenate the Navy.

The Rodgers board, apparently believing a serious question deserved a serious answer, urged that eighteen cruisers and fifty smaller ships be built at once—whereupon it was dismissed. Another board was appointed, which made recommendations that were less far-seeing but, for the moment, more practical. Following its suggestions, Congress provided for three steel cruisers and one dispatch boat, the latter a small ship useful for carrying messages.

Contracts for all four ships, the 4,500-ton Chicago, the 3,000-ton Atlanta and Boston, and the 1,500-ton Dolphin, were awarded to John Roach, a shipbuilder who was also a Republican wheel horse. In 1885 the first of the lot, the Dolphin , was completed; for months she lay alongside her pier, rakish in her standard navy black paint. But Congress and the Presidency had gone to the Democrats in 1884, and the Dolphin was rejected for an assortment of design and mechanical deficiencies. On the advice of friends in the Republican party, who perhaps thought they needed a martyr, Roach, instead of fighting the issue, went into bankruptcy. The Atlanta, Boston , and Chicago were taken over by the government half-built. Not until 1889 was the last of them completed and commissioned.

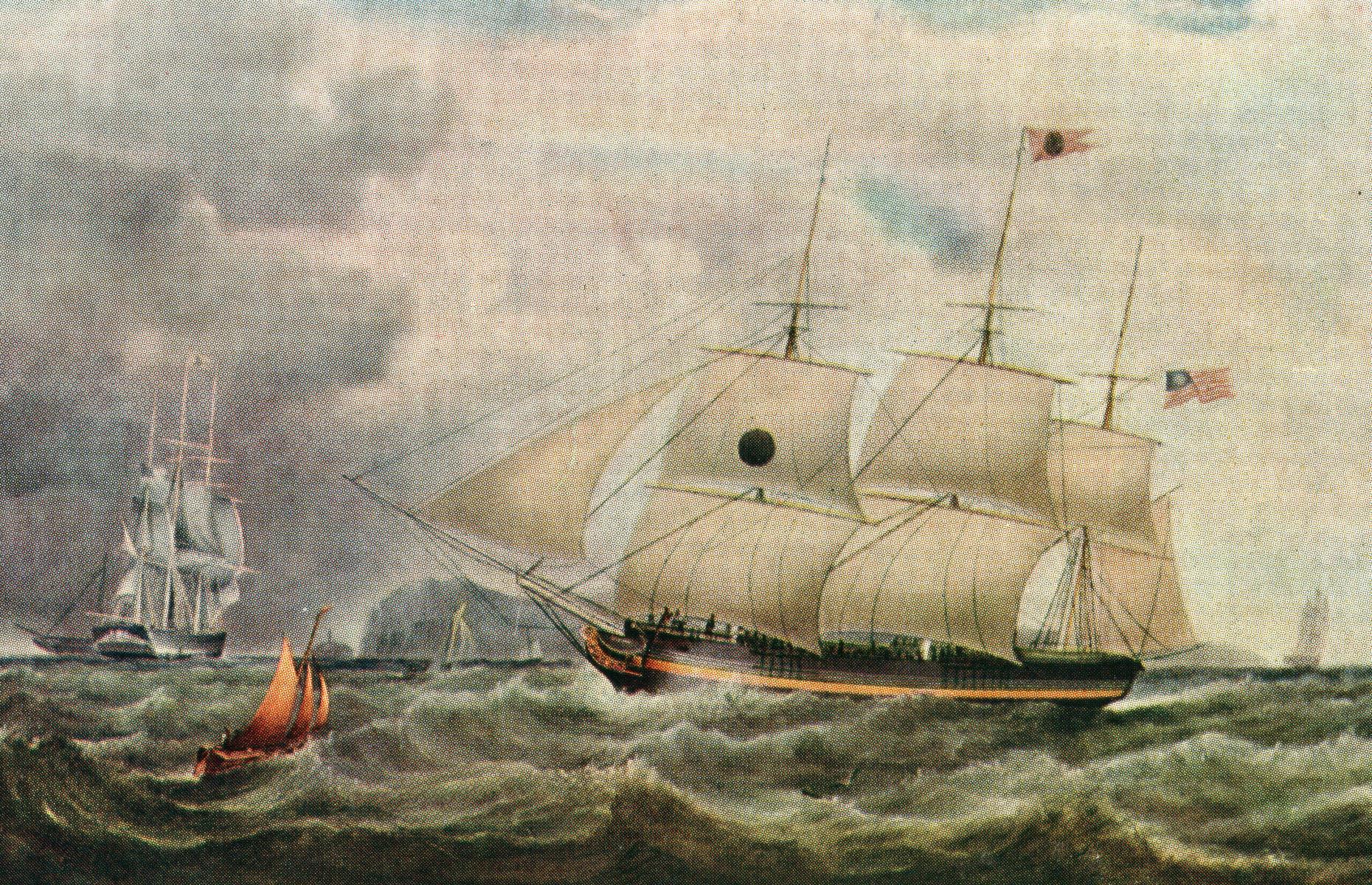

Eventually the Dolphin was accepted, and in 1888 she began a two-year cruise around the world. Men wilted inside her black steel hull as she passed through the tropics. Desperate for a remedy, her captain broke a century-old custom and painted his ship with white lead, thus cooling her interior by several degrees. The Navy Department copied his example; soon all new warships were coming out of their builders’ yards in white. They were quite dashing, with ram bows decorated by gilt scrollwork or American shields, and upper works painted yellow ochre, much like today’s Coast Guard cutters.

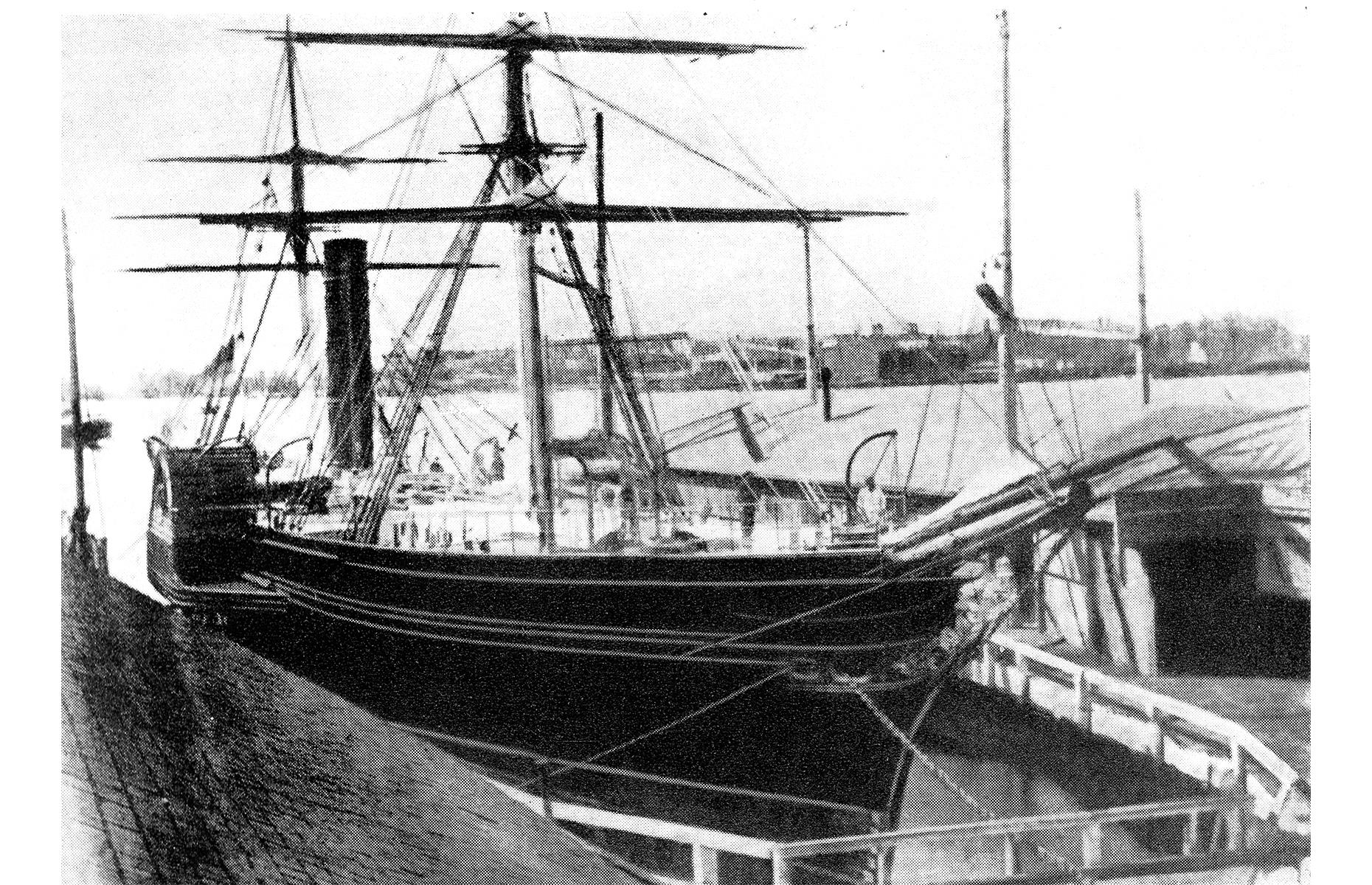

By the end of the decade the first of the Navy’s armored cruisers, Roach’s ships, were at sea, and more were being built. Gradually the old wooden fleet faded away. But American industry, though energetic and willing, had much to learn about building steel warships and supplying their needs. More important, no one in this country was yet competent to design a modem warship. The four ships that the unfortunate Roach built, for example, were all outfitted with a full set of sails in addition to reciprocating steam engines; the Atlanta and Boston were fitted with engines and boilers of a type already outmoded.

Disappointed with American plans, the Navy Department in the mid-eighties went to England and there obtained blueprints for the protected cruisers Charleston and Baltimore , and the second-class battleship Texas . The department was twice stung: the Baltimore proved satisfactory, but the blast from the Texas ’ two 12-inch guns, one on either side of the ship, tore away her upper works. The Charleston ’s, engines were an amalgam of those of four other ships and the parts didn’t fit; she never was made right. From then on, for better or worse, we depended almost exclusively on domestic talent for new designs.

Then, in 1890, Congress authorized the nation’s first real battleships. The appropriation called for “seagoing, coast-line battleships,” a grand contradiction, for a seagoing ship had to be a deep-draft, high-freeboard vessel with lots of room for coal, while a coast-line ship neither needed nor gained from any of these characteristics. At any event, the Navy took advantage of the confusion to build three of the finest warships of the age: Indiana, Massachusetts , and Oregon . Powerfully armed and heavily protected, they made only one concession to the “coast-line” part of the law: they were designed with a low freeboard.

The completion of the Indiana -class battleships, each weighing over ten thousand tons and armed with four 13-inchers, eight 8-inchers, and a variety of smaller guns, would signal a break with the past that was, in its own way, as revolutionary as the building of the first ironclads in the Civil War. Until now, Americans had imagined naval combat in terms of the heavyfooted, short-legged monitors guarding the home shores while swift cruisers like the newly commissioned Columbia and Olympia shot out of the mist to burn enemy—which naturally still meant English—merchant shipping. This was the formula that had worked to a degree in the special circumstances of 1812, when most of England’s great navy had been occupied fighting the French. Under more normal conditions of war, however, it was likely to fail, as it had failed the Confederates in 1861. History showed that the chief business of a navy at war is to destroy or at least lock up the enemy’s fleet. But big ships had always been needed to accomplish this end, and in 1890 that meant steel battleships.

Such was the persuasive argument of Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, the sea-going intellectual who had been elevated from the humdrum of routine duty to head the newly established Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. In 1886, his first year in the post, Mahan had delivered a series of lectures which, four years later, appeared as a book, The Influence of Seapower upon History, 1660–1783 . Though it was essentially a historical work, its implications were much broader, and it had a widespread influence both here and abroad. As the historian Louis M. Hacker has written:

…it was translated into all the important modern languages; it was read eagerly and studied closely by every great chancellory and admiralty; it shaped the imperial policies of Germany and Japan; it supported the position of Britain that its greatness lay in its far-flung empire; and it once more turned America toward those seas where it had been a power up to 1860 but which it had abandoned to seek its destiny in the conquest of its own continent.

Mahan’s message—which in his day seemed revolutionary—was that a strong navy was the key to national power and security. And yet, only with the greatest reluctance did the Navy accept the formulations of this unsociable officer with the scholarly mind. (“It is not the business of a naval officer to write books,” one hard-shell admiral once reminded Mahan when he asked that his next sea tour be put off until he had completed the volume he was then working on.) Gradually, however—and Mahan’s influence is undeniable—the Navy underwent a fundamental transformation: an essentially provincial organization would one day become a sophisticated professional service which knew how to think in terms of war waged across the oceans and around the globe.∗∗ Even in World War II Mahan’s studies were influential in American naval thought, as Secretary of War Henry Stimson discovered when he frequently found himself confronted by that “dim religious world, in which Neptune was God, Mahan his prophet, and the United States Navy the only true Church.”

If the Indiana -class battleships were models of advanced design, many of the ships which entered service in the nineties were obsolescent curiosities. Hardly any two were alike. There was the bizarre Brooklyn , with her huge beaked bow, tumble-home sides, and three slender smokestacks soaring a hundred feet above the furnace grates. There was the long, narrow Vesuvius , which fired shells filled with dynamite from three 15inch pneumatic guns angling out of her fo’c’sle deck, and the Katahdin , armed with a formidable ram upon which she was to impale the foe. So that she might be invisible against her sea background she was painted green, and she could submerge till the deck was awash. Alas! She was too slow to catch any vessel with the wit to get out of the way.

Then there were the low, flat monitors—”about the shape of a sweet potato which has split in the boiling,” wrote a future admiral, William S. Sims, who served for a time in one of them. Six in number, they had raftlike hulls little different from that of John Ericsson’s original Monitor of 1862. If one can accept the faintly cannibalistic idea of one ship absorbing another and quietly assuming her victim’s identity, he can trace the history of most of these craft back to the Civil War.

The old Monadnock , for example, which shortly after the Civil War had smashed her way from east coast to west via the Horn in eight months, was found badly decayed and unseaworthy after a few years. “Repairs” at a private shipyard in San Francisco Bay were authorized in 1873, though work did not actually begin for another three years. By 1883, with the job still not done, the Navy seized the ship, towed her to the nearby Mare Island Navy Yard, and completed her—thirteen years later. When she poked her broad nose out of San Francisco Bay for the first time, in 1898, the only trace of the original Monadnock was the name; all the rest—hull, engines, boilers, and guns—was new. Unfortunately, a design that was good in 1873 had little to recommend it a quarter of a century later.

In spite of this lingering abundance of floating oddities and antiques, it was not a bad fleet, though hardly in a class with the navies of the major European powers. Nor did there seem any likelihood that it would be for years to come. As Admiral Bradley Fiske wrote, years later:

there was absolute conviction in the minds of everybody that the United States would never go to war again, and that our navy was maintained simply as a measure of precaution against the wholly improbable danger of our coast being attacked. It was not considered proper for a nation as great as ours not to have a fine navy; but the people regarded the navy very much as they regarded a beautiful building or fine natural scenery: a thing to be admired and to be proud of, but not to be used.

But a test of America’s new navy came sooner than anyone expected. Affairs in Cuba had not improved since the days of the Virginius incident. In February, 1898, while on a visit to Havana, the battleship Maine blew up, killing 262 men. Spain frantically disclaimed responsibility (the cause of the explosion has never been satisfactorily determined) but to no avail. Two months later, the United States declared war. The fleet went into dull gray paint and loaded ammunition—which had been provided by the foresight of the energetic young New Yorker who was Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodcre Roosevelt. His duty done, Roosevelt resigned to get into the fight with his own mounted regiment of cowboys and college boys.

In Europe, only the British favored an American victory, but they were not hopeful. As Commodore George Dewey led the Asiatic Squadron out’of Hong Kong, the prevailing opinion of the Royal Navy officers was that the Americans were “a fine set of fellows, but unhappily we shall never see them again.”

It didn’t work out that way. Dewey, with four cruisers, two gunboats, a Coast Guard cutter, and two supply ships, entered Manila Bay late in the night of April 30, exchanged a few shots with the forts at Corregidor, and early the next morning encountered Rear Admiral Don Patricio Montojo’s squadron at Cavité, near the head of the bay. Montojo, backed by guns ashore, also had seven cruisers and gunboats, though his ships were older and smaller than Dewey’s. The latter, taking time out in the midst of the action to serve his men breakfast, sank all of Montojo’s ships without losing a man or a ship. Bradley Fiske, a veteran of the battle, noted that after Manila Bay, the British began to look upon the Americans as equals.

The Philippines, however, was a side show; Cuba remained at all times the chief theatre of war. By April, the Navy’s half-dozen big ships in the Atlantic had been concentrated at Key West, and the Pacific Station’s only battleship, the Oregon , was pounding up the east coast of South America at a steady eleven knots, en route to the Florida base.

Meanwhile, somewhere in the Atlantic, Rear Admiral Pasqual Cervera was at sea with the main Spanish squadron—four big armored cruisers accompanied by three torpedo boats. Panicking, the East Coast demanded naval protection. To give the appearance of a defense, Civil War monitors were hastily reconditioned and manned with naval militiamen. The public wanted more. So, despite Mahan’s dictum that the battle fleet should never be broken up, it was. One half of our big ships were formed into the so-called Flying Squadron under Commodore Winfield Scott Schley in the Brooklyn and ordered north to Norfolk, to catch Cervera if he should try to shell coastal cities or beach resorts. It was an unwise move, for both the Flying Squadron and the ships remaining at Key West under Rear Admiral William T. Sampson in the armored cruiser New York were now outnumbered by the Spaniards. Luckily, however, Cervera had neither fuel nor ammunition to waste on civilian targets.

In time the Spanish admiral and six of his ships reached Santiago, on Cuba’s southern coast, where they stopped for coal. After some hesitation, the North Atlantic Fleet, once again united under Sampson, gathered at the entrance to Santiago’s little harbor and dared the foe to venture out. When nothing happened, a naval constructor named Richmond P. Hobson and seven volunteers attempted to trap Cervera by sinking an old merchant ship in the middle of Santiago’s narrow channel. Running in at night under fire from the enemy’s ancient shore batteries, they sank the ship, but she went down lengthwise rather than athwart the channel, and the way remained open.

Next the Army tried to drive Cervera out. In the second half of June some 17,000 troops were landed at Daiquiri, about halfway between Santiago and the recently captured base at Guantanamo Bay. Fighting not only a well-entrenched, though hungry, enemy but heat and tropical disease, the outnumbered American army also failed. The commanding general called upon Admiral Sampson to dash through the enemy’s minefields and collar the Spaniards; he refused. But Sampson was willing to talk the matter over. He was on his way to a conference with the general on Sunday, July 3, when Pasqual Cervera abruptly solved the matter.

Prodded from Madrid, the reluctant Spanish admiral headed out to sea—and provided the American Navy with another great morning. The Americans, led by Sampson’s second-in-command, Commodore Schley, destroyed all of Cervera’s ships without losing a single ship of their own; only one man was killed, a yeoman on the Brooklyn . When Admiral Sampson heard the gunfire, he turned the swift New York around and crowded on all speed, but he arrived too late. His report to Washington, “The fleet under my command offers the nation as a Fourth of July present the whole of Cervera’s fleet … ,” precipitated a bitter wrangle with Schley that went on for years.

Nonetheless there was glory enough for all. Everyone was gallant, officers shouted heroic phrases (“Don’t cheer, boys, the poor devils are dying,” cried Captain Jack Philip of the Texas ), and the scene was bright with flying flags and flaming guns. After the battle the victors risked their lives to rescue their recent enemies from exploding ships, sharks, and Cuban guerrillas on the beach; captured Spanish officers were taken to Annapolis, where they were treated as gentlemen-heroes.

“A splendid little war,” wrote an exultant John Hay from London, and most would agree. Cuba was free after four centuries of Spanish rule and now we had colonies of our own: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. The Navy had become immensely popular. Congress provided for so many new ships that the nation’s shipyards were clogged for years.

Not everyone, however, was as self-satisfied as Hay. Within the Navy serious questions arose about American strategy (splitting the Flying Squadron from the rest of the fleet), tactics (Santiago was a captains’ battle with no direction from Commodore Schley), and gunnery (firing at ranges of a mile or two, only 1.3 per cent of the shots hit home). Perhaps the performance was no worse than anyone else’s might have been. In any event it was better than the Spaniards’, and that was enough for that war.

In September, 1901, Theodore Roosevelt, a political nonconformist whom Republican chieftains had tried to bury in the Vice Presidency, unexpectedly became President when William McKinley was assassinated. For the seven and a half years that Roosevelt was in the White House, the Navy toiled and prospered. Roosevelt was a zestful player at world power politics. He believed not only that “a great country must have a foreign policy,” but also that “there is some nobler ideal for a great nation than being an assemblage of prosperous hucksters.” The Navy became his chief means for executing his views on foreign policy.

Tiny gunboats commanded by officers fresh from Annapolis cruised, ready for battle, up and down the Philippines and far up the pirateridden rivers of China. Others roamed the Caribbean, prepared to land marines and seamen on turbulent tropic shores.

POURED BACK ABOARD

This 1887 engraving from Harper’s Weekly , based on a drawing by Frederic Remington, is titled “The Last Aboard”—referring, of course, to the acrobatic fellow in the blue uniform and leg irons who is being gently assisted to the deck of a U.S. Navy man-of-war. Some siren song of the mainland has obviously smitten him—but a few days in the brig will cure all that. Commenting on this tableau, an anonymous Harper’s moralist spoke of the “certain human tendencies” in sailors “which, for all that one can see, will last to the end of things nautical … In the case of the sailor whose return is represented in the picture … the indisposition to resume the humdrum of a seafaring life is most marked.… His mates understand that he means no offence to them personally by being burdensome, and that his balky behavior is directed merely against the general system of ship discipline, which, on such an occasion particularly, seems very harsh and grinding to him.

“The types of sailors represented,” the writer concluded, “are taken from Uncle Sam’s navy, and may be seen in life just at present at the Brooklyn Navy-yard, where, though satisfactory results have attended the energetic temperance crusade conducted by the worthy chaplain of the Vermont , the backsliders are sufficiently numerous to supply many originals for the subject of our illustration.”

In November, 1903, negotiations with Colombia for a ship canal through the Isthmus of Panama failed. Not long after, that province flared into revolt. When loyal troops arrived at Colon they found the U.S. gunboat Nashville in the harbor and her landing party ashore, effectively blocking the restoration of Colombian authority. Roosevelt quickly recognized Panama as an independent state, and soon had his canal site.

The gunboats may have borne the White Man’s Burden, but they did so under cover of the big ships. Twice war seemed imminent: in 1901, with Germany, when it threatened to slice off a portion of Venezuela in payment for a bad debt, and again, in 1907, with Japan. Twice the President mobilized his battle fleet, and twice the war threat vanished.

During Roosevelt’s administration, the American Navy became, for a time, the second most powerful in the world, boasting more than forty big armored ships—compared with seven during the war with Spain. Only England had more heavy ships (ninety-eight in 1908), while France came third with thirty-three; Germany had thirty-two, and Japan twenty-two. (Russia, long in third place, had been humiliated by the Japanese in 1904–05 and for many years would no longer be counted among the great sea powers.) Germany, Japan, and the United States were on their way up; indeed, after Roosevelt left office in 1909, Germany passed the United States. France was steadily losing ground.

Moreover, from 1905 on, for the first time in peace, most of the American battleships worked together in a single group. And, by previous standards, they were beginning to shoot with marvelous accuracy. While the fleet maneuvered east of Norfolk and south of Cuba, selected officers took graduate courses in strategy, tactics, and international law at the Naval War College in Newport, which Mahan had presided over in its precarious early years.

Then, toward the end of his second term, Roosevelt, always the master showman, came up with the most dramatic stroke of all. With the Japanese war problem still before him, he announced that he would send sixteen of his best battleships from the Atlantic to the Pacific in a show of strength. Dazzling in its white paint, the fleet sailed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, in December, 1907, with Rear Admiral Robley (“Fighting Bob”) Evans leading in his flagship, the Connecticut . The first night out, Evans had a surprise for his 15,000 officers and men: ”… after a short stay on the Pacific Coast, it is the President’s intention to have the fleet return to the Atlantic Coast by way of the Mediterranean.” They were going to steam around the world. The voyage of the “Great White Fleet,” which was to take it 45,000 miles in fourteen months, had begun.

As the Panama Canal was far from finished, the ships made the long first leg of their voyage by way of Rio, the Strait of Magellan, and the west coast of South America. The fleet’s first foreign port was Port of Spain, Trinidad, where it was received with indifference, for the arrival of the Americans coincided with the opening of the horse-racing season. Their reception in Rio was much better. Officers and men alike had a good time. Perhaps the most noteworthy outcome of the occasion was the birth of the Shore Patrol. Evans was determined that his men, let loose in a glittering foreign capital, would be neither the cause nor the victims of trouble. The men did well by their admiral, and the city by the men. Even so, the Shore Patrol proved itself so effective that it has now become an institution, in evidence wherever a naval base is located or in whatever port a U.S. man-of-war may visit.

Buenos Aires also wished to entertain the Americans, but its ship channel was too shallow, and the fleet passed on. Not, however, before it had received a graceful salute, far at sea, from a squadron of neatly handled green-hulled Argentine cruisers. Farther south the fleet stopped at Punta Arenas on the Strait of Magellan, where the stores advertised special prices for the Americans. They were special, too. Twenty-five-dollar fox skins were available at forty, and seal, normally sold at fifty dollars, could be had for seventy-five.

The last part of the passage through the mountainrimmed Magellan Strait was made through fog so thick that one could see neither the ship 400 yards ahead nor the one 400 yards astern—the interval that the battleships of the Great White Fleet normally maintained at all times. Eventually the last ship felt her bow rise on a broad Pacific swell, and all were safe once more.

Now the white column steamed north and at Valparaiso Bay saluted the President of Chile. Less than twenty years earlier Evans, in a gunboat, had been involved in that very same bay in an unpleasantness which nearly caused war between Chile and the United States. Two U.S. Navy men had been killed in a riot arising from a barroom brawl, and it was largely Evans’ tact which prevented a major incident. But cordiality was the order now—as it was at Callao, the seaport to the Peruvian capital, Lima, where the fleet was entertained by bullfights. It continued north to Magdalena Bay, Mexico. There, by arrangement with the Mexican government, the Americans were able to spend a month at target practice, drill, and sports. Then they went on to California, where Admiral Evans, painfully ill with rheumatism, gave up his command.

After the men were banqueted at every port from San Diego to Seattle, Evans’ replacement, Rear Admirai Charles S. Sperry, took the fleet to sea again, heading out across the Pacific in the beginning of July. The first stop was Honolulu. Chief turret captain Roman J. Miller of the Vermont , visiting nearby Pearl Harbor, found that though it was yet undeveloped, it was “from a naval point of view, a very important place.” Leaving the Hawaiian Islands, the ships proceeded on a leisurely roundabout voyage, with stops at New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, and Japan.

The Japanese, who only a short time before had been threatening war, received their white-hulled visitors with “cordiality … amounting often to actual frenzy,” as one participant remembered. The Americans did more than enjoy the cordiality. Observing the Japanese fleet in dark war paint, many officers recommended that our ships also be painted for war at all times. To leave the ships white until strained relations occurred with another country and then to change their color would be, as one naval officer has pointed out, “an overt act that might precipitate the very enemy action that the diplomats might otherwise be able to forestall.” The recomended change was put into effect within a few months, and our ships have worn gray in one shade or another ever since.

After Japan, the fleet was temporarily split—for target practice off Manila and on the China coast. Then, entering the Indian Ocean, the ships steamed for home. The long passage was broken only by a visit to Ceylon; there the American sailors from the farms of Kansas and Georgia caught glimpses of native villages hidden away in groves, far up in the mountains, and tea or rubber plantations. When the fleet arrived at Suez, in January, 1909, word came of an earthquake at Messina, in Sicily, which had killed 60,000 people. Help was desperately needed. One ship from the fleet was loaded with medical supplies and rushed ahead. Arriving ten days after the disaster, the rescue crews could do little but search for bodies.

On February 22, 1909—Washington’s Birthday—the Great White Fleet steamed home at last, to be welcomed at Hampton Roads by T. R. in the presidential yacht Mayflower . The occasion marked his last significant accomplishment as Chief Executive; ten days later, he left the White House for good. It was an impressive end to a notable presidential career; in his autobiography Roosevelt could write with justifiable pride that the voyage of the Great White Fleet was “the most important service I rendered peace.” As he said in a speech to Admiral Sperry and his men:

You have falsified every prediction of the prophets of failure. In all your long cruise not an accident worthy of mention has happened.… As a war machine, the fleet comes back in better shape than it went out. In addition, you, the officers and men of this formidable fighting force, have shown yourselves the best of all possible ambassadors and heralds of peace.… We welcome you home to the country whose good repute among nations has been raised by what you have done.

The accomplishments of the Great White Fleet had been numerous indeed. In his report for 1909 the Secretary of the Navy stated that the cruise “increased enlistments and enabled the Bureau of Navigation to recruit the enlisted force to practically its full strength,” a pleasing development in a period when few American boys thought seriously of joining the Navy. Moreover, the Secretary was able to report, “There has been a gratifying decrease in the percentage of desertions, which has dropped from 9 to 5½ per cent during the past year.”

The officers and men learned a great deal, too. They learned how to get the greatest economy out of their engines, the most mileage per ton of coal. Because they had no navy yards handy, they learned that to a great degree they could maintain their ships themselves. They learned to place their ships accurately on station during tactical drills and battle exercises, and to keep them there. At Magdalena Bay, early in the cruise, Admiral Evans said to one of his captains, “I hope your officers have learned something …” The captain replied, “Thirteen thousand miles at four hundred yards, night and day, including the Strait of Magellan; yes, they have learned a lot!”

More important, the cruise of the Great White Fleet demonstrated beyond question that the United States was now a world power. Those battleships, as they dipped their curved beaks into the rollers of the Pacific, the calm stretches of the Indian Ocean, and the white-flecked Mediterranean, were dramatic evidence of the radical change of course which this country, however unwitting and unwilling, had now taken.

We hope you enjoy our work.

Please support this magazine of trusted historical writing, now in its 75th year, and the volunteers that sustain it with a donation to American Heritage .

© Copyright 1949-2023 American Heritage Publishing Co . All Rights Reserved. To license content, please contact licenses [at] americanheritage.com.

A Lasting Legacy: The Ships of the Great White Fleet

One of Theodore Roosevelt’s biggest accomplishments as president was the complete transformation and buildup of the US Navy. The culmination of his efforts led to the famed round the world cruise of the ships of “The Great White Fleet” from 1907-1909.

The fleet of 16 battleships was meant to display newfound American power and show the world that the US was ready to step into global affairs. Over the past century and dating back to its founding, the United States had favored more of an isolationist policy and kept out of European affairs.

George Washington’s farewell address and the Monroe Doctrine were very influential in early American policy. These aimed for the country to avoid entanglements with foreign nations and warned European nations of encroaching and meddling in the affairs on the American continents.

With the outbreak of the Civil War and the following period of Reconstruction, the US was too occupied with its own internal strife to play any sort of role in global affairs. Upon the conclusion of the Spanish American War in 1898, the US suddenly found itself in possession of several overseas territories.

These territories spanned the globe, including the Pacific Islands of Guam and the Philippines. In order to maintain and protect these territories, the US needed to modernize its Navy. During the 1880s, the country began this process.

The relative strength of the US Navy was a major reason for the ease of victory in the Spanish-American War. After rising to the position of Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897, Theodore Roosevelt stressed even more the importance of a strong Navy.

First Squadron:

Second squadron:, connecticut class, virginia class, maine class, illinois class, kearsarge class, the ships of the great white fleet.

Through Roosevelt’s efforts as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and then as President, Congress designated funds to completely modernize the US Navy and showcase US strength. Roosevelt believed that a strong navy was essential to American interests and important part of his Roosevelt Corollary doctrine . As he stated in a 1902 speech to Congress:

The United States began building battleships at a remarkable pace. Within two decades the US was relatively in line with the likes of the United Kingdom and Germany. In fact, by 1908 the United States navy was the second most powerful in the world, behind only the British Royal Navy. 1

With their hulls painted a bright white, on December 16th, 1907, the ships of the “Great White Fleet” set off on a 14 month round the globe trip. The Navy divided the ships into two squadrons of eight ships each, and further divided within each squadron into two divisions of 4 ships each. The participating ships included:

- USS Connecticut ( Connecticut class) – flagship

- USS Kansas ( Connecticut class)

- USS Vermont ( Connecticut class)

- USS Louisiana ( Connecticut class)

- USS Georgia ( Virginia class)

- USS New Jersey ( Virginia class)

- USS Rhode Island ( Virginia class)

- USS Virginia ( Virginia class)

- USS Minnesota ( Connecticut class)

- USS Maine ( Maine class)

- USS Missouri ( Maine class)

- USS Ohio ( Maine class)

- USS Alabama ( Illinois class)

- USS Illinois ( Illinois class)

- USS Kearsarge ( Kearsarge class)

- USS Kentucky ( Kearsarge class)

These were the capital ships of the US Navy at the time, with some being completed as recently as that same year (1907). In an ironic twist, these ships were all essentially obsolete by the time of their voyage meant to showcase American strength. The two ships of the oldest class ( Kearsarge ) were outdated and unfit for battle.

These battleships were all pre-dreadnoughts. With the rapidly advancing naval technology of the times, the British completed the HMS Dreadnought in 1906. It revolutionized ship design and its capabilities far outclassed any pre-dreadnought battleships.

At the time of the Great White Fleet’s voyage, the US itself had already begun construction of its own first dreadnoughts, following President Roosevelt’s massive push to continually invest in a modern and powerful navy. 2

While technically obsolete, the ships of the Great White Fleet served its purpose. The world was put on notice for the burgeoning American power.

The Connecticut class was the penultimate class of pre-dreadnought US Navy ships. The Navy built six total ships between 1903-1908 with the first completed and commissioned in 1906.

Five of the six ships were among the Great White Fleet. Only the USS New Hampshire , which had not been commissioned yet, did not take part.

The Connecticut class ships were in commission from 1906-1923, though all decommissioned as part of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty.

The Virginia class was a class of pre-dreadnought US Navy ships. The Navy built five total ships between 1902-1907 with the first completed and commissioned in 1906. They were the first ships to incorporate design changes from lessons learned in the Spanish American War.

Four of the five ships were among the original ships of the Great White Fleet. The USS Nebraska joined the fleet after replacing the USS Maine in San Francisco. The USS Maine had been experiencing mechanical issues.

The Virginia class ships were in commission from 1906-1920, though all officially decommissioned as part of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty.

The Maine class was a class of pre-dreadnought US Navy ships. Congress commissioned three total ships for construction between 1899-1904 with the first completed and commissioned in 1902.

All three ships were among the original ships of the Great White Fleet. The USS Maine was replaced by the USS Nebraska in San Francisco after experiencing mechanical issues.

The Maine class ships were in commission from 1902-1920, though all withdrawn from service between 1919-1920 and later sold for scrap.

The Illinois class was a class of pre-dreadnought US Navy ships. The Navy built three total ships between 1896-1898 with the first completed and commissioned in 1900.

Two of the three ships were among the original ships of the Great White Fleet, though all three eventually took part. The USS Alabama was replaced by the USS Wisconsin ( Illinois class) in San Francisco after experiencing mechanical issues.

The Illinois class ships were in commission from 1901-1920, though all withdrawn from service between 1919-1920 and later sold for scrap.

The Kearsarge class was a class of pre-dreadnought US Navy ships. The Navy built two total ships between 1896-1898 with the first completed and commissioned in 1900.

Both ships were among the original ships of the Great White Fleet. They were the oldest ships to sail in the fleet and not fit for battle due to their technological inferiority.

The Kearsarge class ships were in commission from 1900-1920, though both withdrawn from service between 1919-1920. Despite a last push for a ceremonial sinking in the sea, the Kearsarge class ships were later sold for scrap in 1923. 3

To learn more about US history, check out this timeline of the history of the United States .

1) McMahon, Christopher. “THE GREAT WHITE FLEET SAILS TODAY?: Twenty-First-Century Logistics Lessons from the 1907–1909 Voyage of the Great White Fleet.” Naval War College Review , vol. 71, no. 4, 2018, pp. 67–90. JSTOR , https://www.jstor.org/stable/26607090 .

2) Foppiani, Oreste. “THE WORLD CRUISE OF THE US NAVY IN 1907-1909.” Il Politico , vol. 71, no. 1 (211), 2006, pp. 110–40. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/24005543 .

3) Gillig, John S. “The Predreadnought Battleship USS Kentucky.” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society , vol. 88, no. 1, 1990, pp. 45–81. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/23381829 .

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter!

Other posts you may like:.

Understanding the Purpose and Significance of the Roosevelt Corollary

Why Was the 1781 Battle of Yorktown Important?

The Monumental Battle of Vicksburg (Significance + Importance)

The Devastating Firebombing of Japan (Tokyo + Others)

The Significance of the Pequot War of 1637

The 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers (Significance + Summary)

How Many People Died Building the Panama Canal?

Why did the Schlieffen Plan Fail? (3 Reasons)

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was a fleet of U.S. Navy ships that sailed around the world for the purpose of displaying the naval power of the United States.

The Great White Fleet by John Charles Roach. Image Source: National Archives .

Great White Fleet Summary

The Great White Fleet (1907–1909) was a fleet of 16 U.S. Navy ships — painted white — that sailed around the world for the purpose of displaying the naval power of the United States to Japan and other nations. The fleet was dispatched by President Theodore Roosevelt in an effort to ease tensions with Japan, which was rumored to be considering war with the U.S. over the treatment of Japanese people living in America. The fleet visited ports of call around the world and effectively demonstrated the naval power of the United States.

Great White Fleet Facts — 10 Things to Know

- There were a total of 18 battleships from the U.S. Navy Atlantic Fleet that participated in the voyage of the Great White Fleet.

- The hulls of the ships were painted white because the ships were on a peace mission.

- The fleet consisted of two squadrons and each squadron contained two divisions of 4 ships.

- Approximately 14,5000 U.S. sailors gained experience on the voyage of the Great White Fleet.

- The Great White Fleet set sail from Hampton Roads, Virginia on December 16, 1907.

- The fleet returned to Hampton Roads on February 22, 1909.

- Throughout its voyage, the Great White Fleet sailed more than 40,000 miles.

- The fleet visited 20 ports of call on 6 continents.

- At that point in time, the Great White Fleet was the most powerful naval force that had ever sailed around the globe.

- The Great White Fleet demonstrated the capabilities of the U.S. Navy and indicated the necessity of having supply stations available around the world.

Great White Fleet History

President Theodore Roosevelt believed the United States should “speak softly and carry a big stick” in terms of foreign policy, meaning the U.S. should take a strong diplomatic approach backed by military might.

Roosevelt’s Big Stick Policy in the Western Hemisphere

In Latin America and the Caribbean, it was called “Big Stick Diplomacy,” and he used military might to enforce it when dealing with certain situations, especially in Venezuela in 1902 and Cuba in 1906.

Roosevelt’s Open Door Policy in Asia

When it came to Asia, Roosevelt took a different approach, because the United States needed access to markets in China. His policy toward East Asia was known as the “Open Door Policy,” and he worked to maintain the balance of power in the region, allow all nations to have access to China, and provide support for the Chinese government.

The policy was partially developed in response to the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1701) . Following the conflict, Russia stationed troops in the region, leading to the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) . In this conflict, Russia and Japan fought for greater influence in the region.

While Roosevelt supported Japan’s desire to become a global power, the U.S. stayed neutral in the conflict. Roosevelt helped negotiate the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth that ended the war and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts — becoming the first American to win the award.

Roosevelt supported Japan for two main reasons:

- He wanted Japan to expand its influence within the region.

- He wanted to strengthen U.S. ties with Japan.

Yellow Peril in the United States

Unfortunately, Roosevelt’s plan was faced with growing anti-Asian sentiment in the United States, which was called “Yellow Peril.” The main examples of this were found in California, where the state passed laws limiting immigration from East Asia, and San Francisco segregated schools, separating white children and Asian children.

Yellow Peril policies led to outrage in Japan, and some pro-military factions even suggested the possibility of war with the United States. To ease the growing tension, President Roosevelt worked to find a solution.

Gentleman’s Agreement with Japan

In 1907, Roosevelt came to an informal agreement with Japan, known as the “Gentleman’s Agreement.” Under the agreement, Japan agreed to stop issuing passports for immigration to the United States, and Roosevelt agreed to force the San Francisco school board to reverse its segregation policy.

Pacific Coast Race Riots of 1907

Despite the agreement, anti-Asian sentiment reached a critical point in 1907 when a series of race riots took place in the United States and Canada, along the West Coast.

The major riots took place in San Francisco, California, Bellingham, Washington, and Vancouver, British Columbia. The San Fransico Riot started on May 10, 1907, when Californians attacked Japanese immigrants.

Rumors that Japan intended to declare war on the United States over the treatment of Japanese living in the U.S. Although Roosevelt did not believe Japan would go to war, he met with his military advisors in June 1907 to discuss options for dealing with the threat.

Voyage of the Great White Fleet

Roosevelt and his advisors decided to send a group of newly commissioned battleships from the U.S. Navy on a world tour. Collectively, the ships became known as the “Great White Fleet,” because their hulls were painted white. The fleet consisted of 16 ships and they traveled 45,000 miles over 14 months, demonstrating U.S. naval power to the entire world — especially Japan.

The Great White Fleet was under the command of Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans and the USS Connecticut served as the flagship. The fleet set sail on December 16, 1907, from Hampton Roads, Virginia.

From Hampton Roads, the fleet sailed to the Caribbean, where it visited the British West Indies. From there it went to South America and Mexico, stopping at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Sandy Point in Chile, Callao in Peru, and Magdalena Bay in Mexico.

The fleet departed Mexico and sailed up the West Coast to San Francisco, where it arrived on May 6, 1908. By the time the fleet arrived in San Francisco, Admiral Evans was suffering from health issues. At San Francisco, he was replaced by Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry.

The Great White Fleet left San Francisco on July 7, 1908, stopping at ports in Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippine Islands, Japan, and Ceylon. The fleet’s final stop was on January 3, 1909, at Suez, Egypt.

Great White Fleet and the Messina Earthquake

While the fleet was en route to Egypt, a strong earthquake struck the Strait of Messina in southern Italy. Soon after the fleet arrived in Egypt, the Connecticut and Illinois , along with some support ships were sent to Messina to provide support for the victims of the earthquake. While there, crewmen from the Illinois recovered the bodies of the American consul, Arthur S. Cheney, and his wife, Laura, who were killed in the earthquake.

The Great White Fleet Returns to the United States

On January 9, 1909, the fleet left Messina and made stops in Naples, Italy, and Gibraltar. The voyage concluded when the ships arrived at Hampton Roads, Virginia, on February 22, 1909. President Roosevelt was there to greet the fleet and review it upon its return.

Ships and Captains in the Great White Fleet

First leg of the voyage — commanders, ships, and captains.

On the first leg of the voyage, the Great White Fleet sailed from Hampton Roads to San Francisco, covering 14,556 nautical miles.

First Squadron, First Division — Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans

- Connecticut , Captain Hugo Osterhaus

- Kansas , Captain Charles E. Vreeland

- Vermont , Captain William P. Potter

- Louisiana , Captain Richard Wainwright

Second Division — Rear Admiral William H. Emory

- Georgia , Captain Henry McCrea

- New Jersey , Captain William H. H. Southerland

- Rhode Island , Captain Joseph B. Murdock

- Virginia , Captain Seaton Schroeder

Second Squadron, Third Division — Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas

- Minnesota , Captain John Hubbard

- Maine , Captain Giles B. Harber

- Missouri , Captain Greenlief A. Merriam

- Ohio , Captain Charles W. Bartlett

Fourth Division — Rear Admiral Charles M. Thomas

- Alabama , Captain Ten Eyck De Witt Veeder

- Illinois , Captain John M. Bowyer

- Kearsarge , Captain Hamilton Hutchins

- Kentucky , Captain Walter C. Cowles

First Leg of the Voyage — Ports of Call

- December 16, 1907 — Hampton Roads

- December 23–29, 1907 — Port of Spain, Trinidad

- January 12–21, 1908 — Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- February 1–7, 1908 — Punta Arenas, Chile

- March 12–April 11, 1908 — Magdalena Bay, Mexico

- May 6, 1908 — San Francisco, California

Second Leg of the Voyage — Commanders, Ships, and Captains

The second leg of the Great White Fleet’s voyage was short. The ships traveled from San Francisco north to Puget Sound.

First Squadron, First Division — Rear Admiral Charles S. Sperry

- Vermont, Captain William P. Potter

Second Division — Rear Admiral Richard Wainwright

- Georgia , Captain Edward F. Qualtrough

- Nebraska , Captain Reginald F. Nicholson

- New Jersey , Captain William H.H. Southerland

- Rhode Island , Captain Joseph B. Murdock.

Second Squadron, Third Division — Rear Admiral William H. Emory

- Louisiana , Captain Kossuth Niles

- Virginia , Captain Alexander Sharp

- Missouri , Captain Robert M. Doyle

- Ohio , Captain Thomas B. Howard

Fourth Division — Rear Admiral Seaton Schroeder

- Wisconsin , Captain Frank E. Beatty

- Kentucky , Captain Walter C. Cowles — Callao, Peru

Second Leg of the Voyage — Ports of Call

The ships arrived at Puget Sound on May 23, 1908, and then split up to visit several ports, including Seattle and Tacoma. The fleet regrouped at Seattle on May 23 and left on May 27, sailing to San Francisco.

Third Leg of the Voyage — Commanders, Ships, and Captains

On the third leg of its voyage, the Great White Fleet sailed from San Francisco to Manila, covering 16,336 nautical miles.

Third Leg of the Voyage — Ports of Call

- July 7, 1908 — San Francisco, California

- July 16–22, 1908 — Honolulu, Hawaii

- August 9–August 15, 1908 — Auckland, New Zealand

- August 20–28, 1908 — Sydney, Australia

- August 29–September 5, 1908 — Melbourne, Australia

- September 11–18, 1908 — Albany, Australia

- October 2–9, 1908 — Manila, Philippines

- October 18–25, 1908 — Yokohama, Japan

- October 29–November 5, 1908 — Amoy, China (Second Squadron)

- October 31, 1908 — Manila, Philippines (First Squadron)

- November 7, 1908 — Manila, Philippines (Second Squadron)

Fourth Leg of the Voyage — Commanders, Ships, and Captains

The commanders, ships, and captains during the fourth leg of the Great White Fleet’s voyage were the same as the third leg. The fourth and final leg of the journey was from Manila to Hampton Roads, covering 12,455 nautical miles.

Fourth Leg of the Voyage — Ports of Call

- December 1, 1908 — Manila, Philippines

- December 13–20, 1908 — Colombo, Ceylon

- January 3–6, 1909 — Suez, Egypt (some ships departed on January 4 for Italy)

- January 31–February 1, 1909 — Gibraltar

- February 22, 1909 — Hampton Roads, Virginia

Great White Fleet Significance

The Great White Fleet is important to United States history for the role it played in showcasing U.S. military power to the world, including Japan. Ultimately, the Great White Fleet’s show of force helped reduce tension with Japan. At the same time, the Great White Fleet also showed the willingness of the United States to aid in humanitarian efforts by providing support for victims of the Messina Earthquake.

Great White Fleet APUSH, Review, Notes, Study Guide

Use the following links and videos to study the Great White Fleet and Theodore Roosevelt for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Great White Fleet Definition APUSH

The Great White Fleet for APUSH is defined as a historic U.S. Navy expedition from 1907 to 1909, during the Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Comprising a fleet of sixteen white-painted battleships, it circled the globe as a show of American naval power and a demonstration of the nation’s sea power. The expedition aimed to promote diplomacy and deter potential adversaries while showcasing the United States as a rising global power. The Great White Fleet played a significant role in the emergence of the United States as a major naval force on the world stage in the early 20th century.

Great White Fleet Video for APUSH Notes

This video from LionHeart Filmworks covers the history of the U.S. Navy from the Civil War to the voyage of the Great White Fleet.

- Written by Randal Rust

This section of the HG&UW site created and maintained by Andrew Toppan . Copyright © 1997-2003, Andrew Toppan. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction, reuse, or distribution without permission is prohibited.

Love Exploring

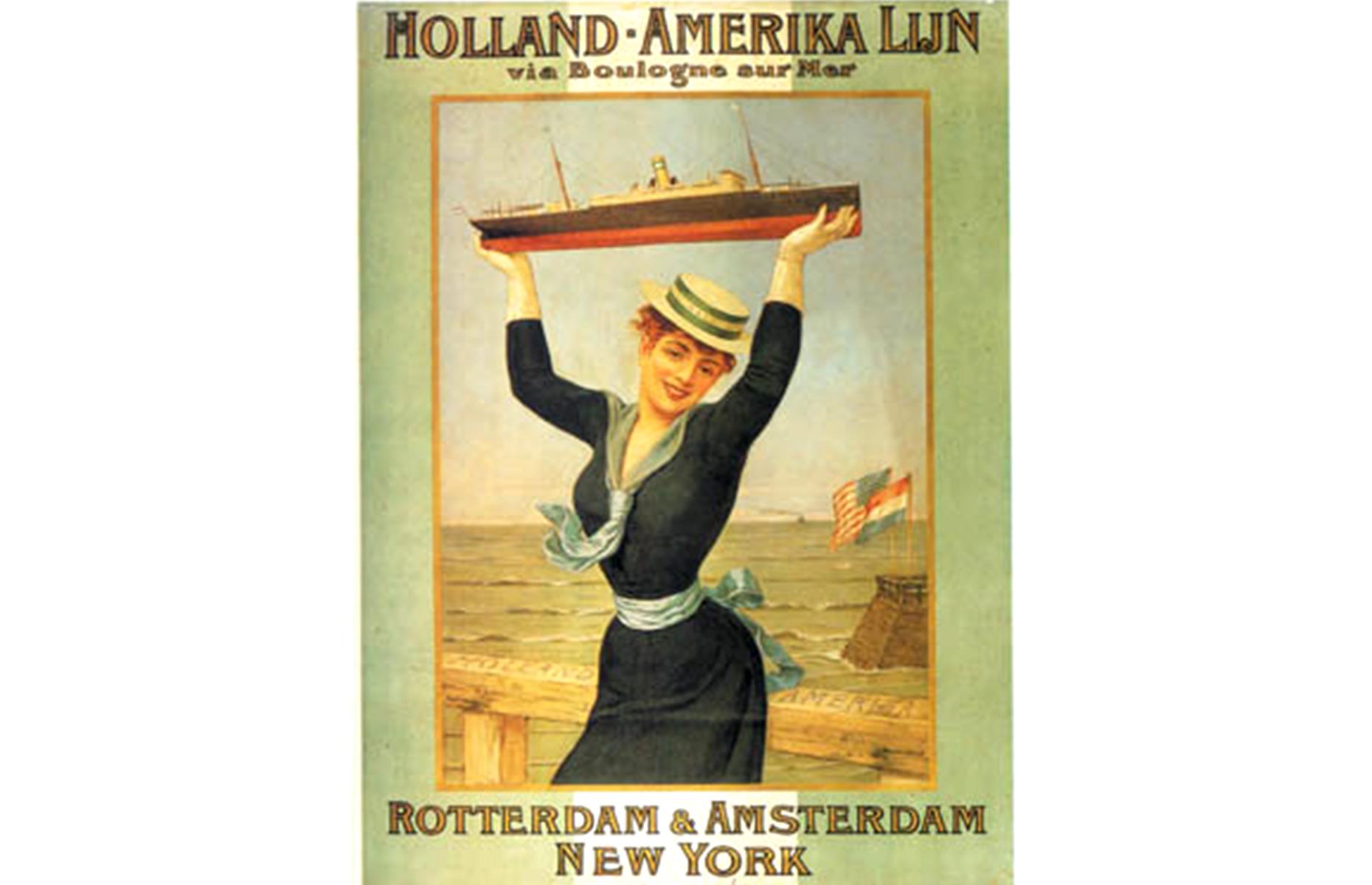

A Retro Look At Cruises Through The Decades

Posted: November 29, 2023 | Last updated: November 29, 2023

Sailing through time

1830s: the very beginnings

1840s: the first pleasure cruises

1840s: a landmark in cruise-line history

1850–60s: early developments

Passenger cruising continued to develop through the mid-19th century, with luxuries like on-board lounges and simple entertainment emerging. Shown here, in 1856, is Cunard's RMS Persia, one of the largest ships of her time and an early Blue Riband winner (an award given for high-speed Atlantic crossings).

1870s: the New World

1880s: lighting up the ocean

1890s: “floating palaces”

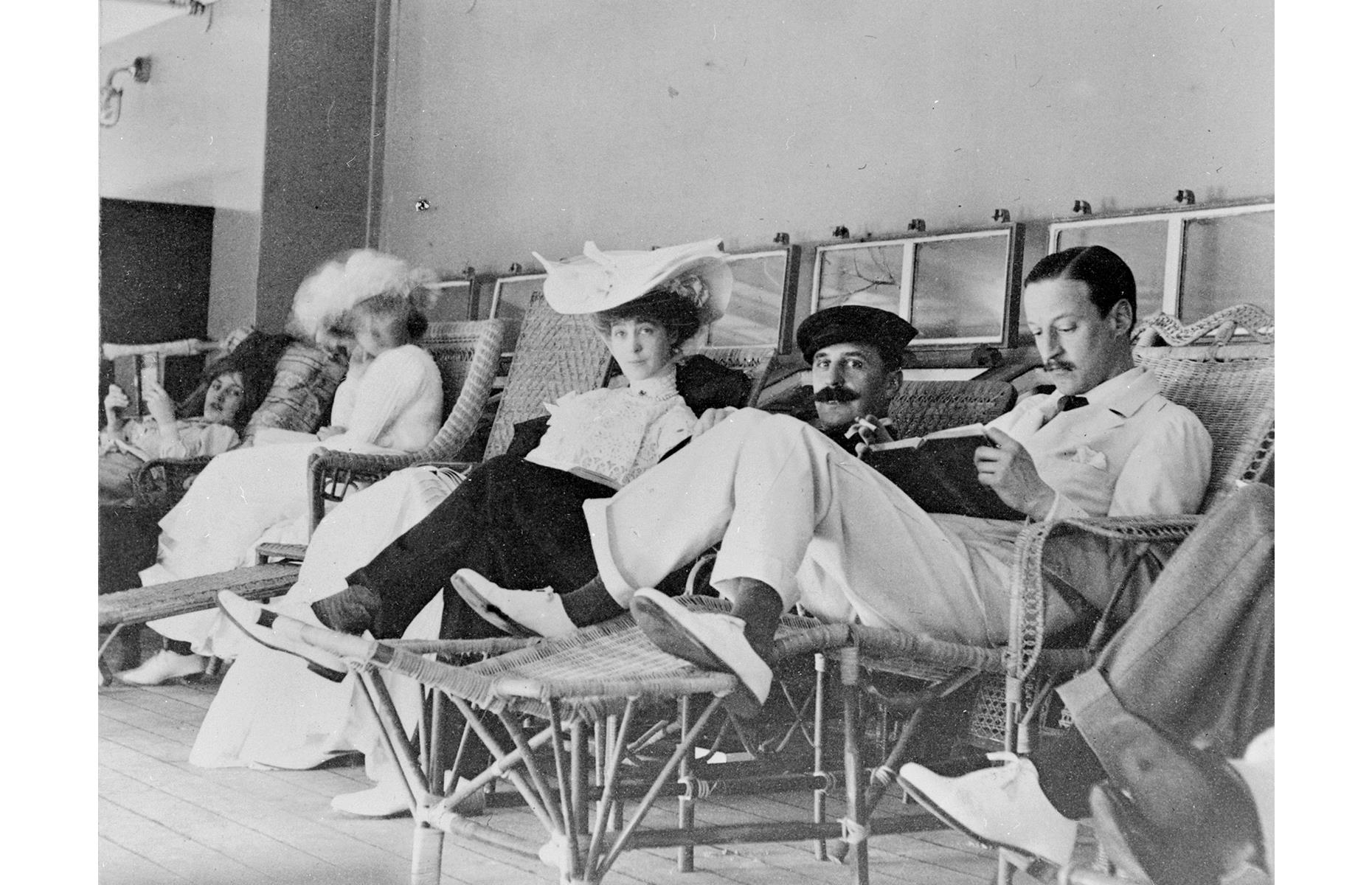

1900s: entering cruising’s golden age

At the turn of the century, there was still a frisson around cruising and large, buzzy crowds would often gather to see off the ships. This nostalgic photograph was snapped between 1900 and 1915, and shows large steam boats leaving from the White Star Line dock in Detroit, Michigan. Well-dressed passengers fill the ships' upper and lower decks too.

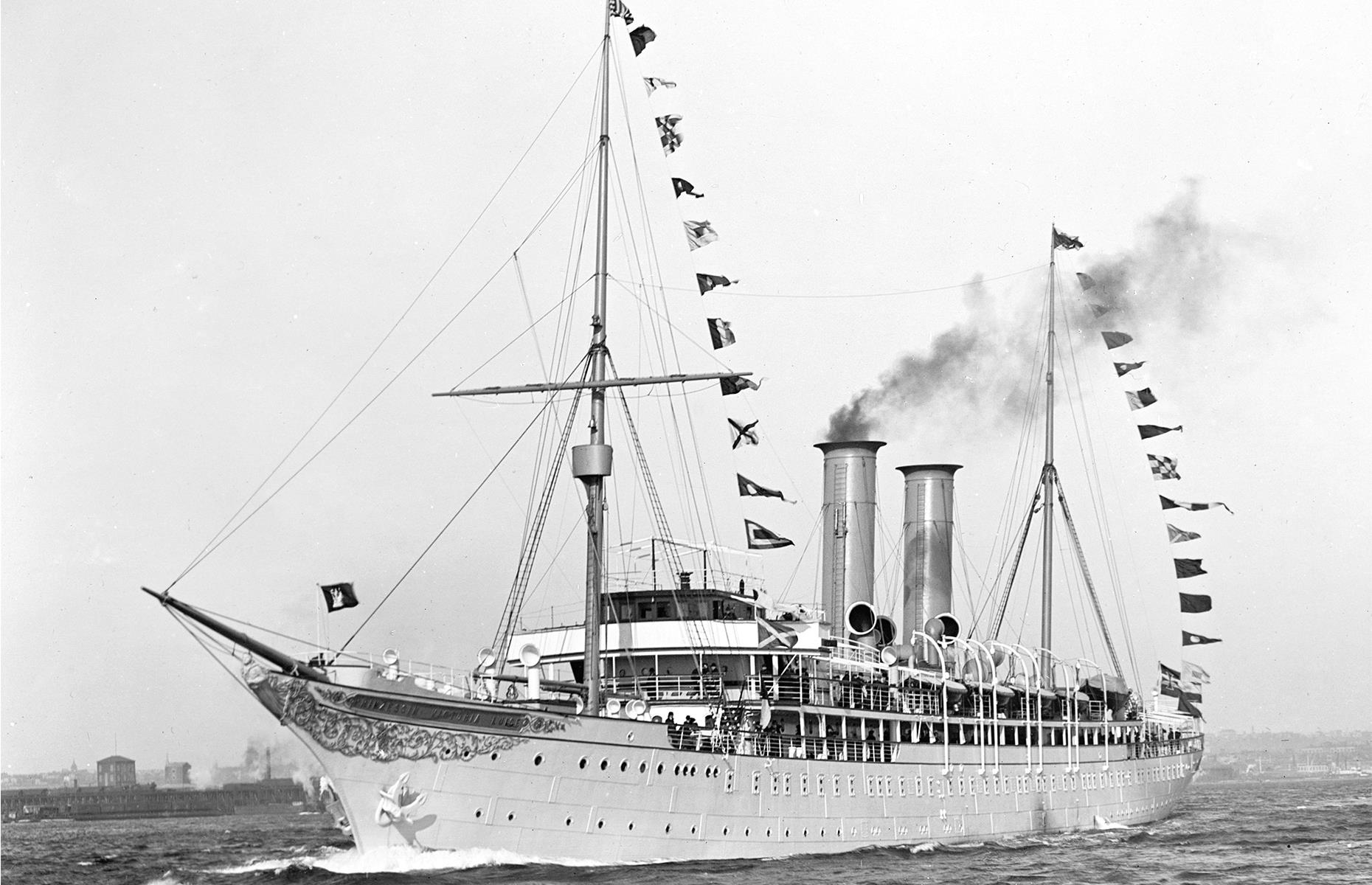

1900s: the first purpose-built cruise ship

1910s: onboard entertainment

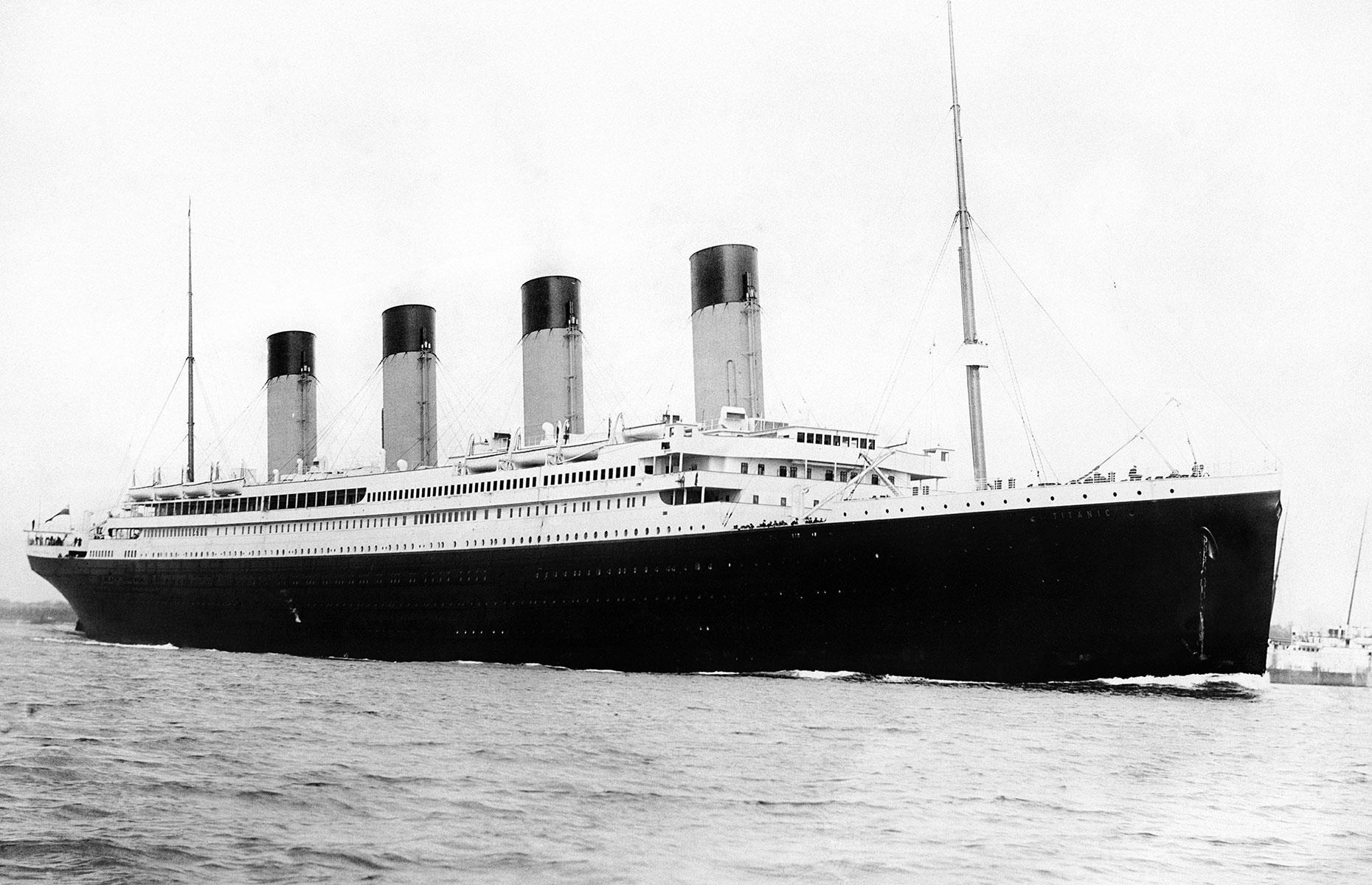

1910s: the Titanic disaster

One of the most famous and devastating events in cruise history occurred in this decade. Dubbed "unsinkable" by the White Star Line's vice-president, the Titanic set out from Southampton on her maiden voyage on 10 April 1912 to much applause. But just four days later, she collided with an iceberg in the North Atlantic: the compartments in her hull filled with water and she tragically sank. The disaster claimed the lives of more than 1,500 people.

1910s: First World War

1920s: cruising’s golden age continued

1920s: setting the bar high

1920s: a festive feast

1920s: the first round-the-world cruise

Another major milestone came in the 1920s: the very first round-the-world cruise. The Cunard Line's RMS Laconia (pictured here leaving Liverpool circa 1920) sailed around the globe in 1922, calling at 22 ports along the way, and taking 450 lucky passengers with her.

1930s: all games on deck

1930s: making a splash

1940s: post-war cruising

1950s: the post-war decades

Come the 1950s, cruise ships had another phenomenon to compete with: jet planes. Commercial air travel boomed in this decade, with comfier aircraft and improved routes enticing travelers into the skies. Many cruise liners underwent swish post-war refits in an attempt to stay afloat: this 1950s photo shows the opulent dining room of French liner SS Île de France after a dramatic post-war makeover.

1950s: going Down Under

1950s: the Blue Riband record breaker

Though formalized in the 1930s, the Blue Riband – the award for the passenger cruise liner with the fastest Atlantic-crossing time – has its roots right back in the 19th century. The record is still held by SS United States of United States Lines, which first sped across the Atlantic in 1952. She's pictured here on 9 July 1952, docking in Southampton.

1960s: the Jet Age

1970s: The Love Boat

As flying became more commonplace, the popularity of cruising looked set to dwindle. However, one particular TV series is often credited with keeping travelers' passion for cruising alive. The Love Boat – aired from the 1970s – was a comedy series that followed the crew and passengers of luxury liner SS Pacific Princess. Such was its popularity, some say it brought cruising back into the mainstream once more. This shot shows Cunard Line's Queen Elizabeth 2 in 1975.

1970s: cruising opens up to the masses

1980s: the cruise to nowhere

The 1980s is thought to be the decade that pioneered the "cruise to nowhere," where the ship really was the destination. The SS Norway (pictured) – a lavish mega ship with room for thousands of passengers and amenities like a casino – embarked on a no-docking cruise in this decade.

1990s: Disney takes to the water

2000s: making waves in the modern world

The 2000s saw larger-than-life, no-expense-spared, mega cruise ships sail onto the scene. This sunset snap shows Cunard Line's Queen Mary II as she completes her first trans-Atlantic voyage in January 2004. At this time, she was the largest and most expensive cruise ship ever constructed with room for 2,200-plus passengers, a theater and even a planetarium, setting the bar for the ships of posterity.

2010s: bigger, better and healthier

2020s: off to a rocky start