share this!

September 24, 2020

Young physicist 'squares the numbers' on time travel

by University of Queensland

Paradox-free time travel is theoretically possible, according to the mathematical modeling of a prodigious University of Queensland undergraduate student.

Fourth-year Bachelor of Advanced Science (Honours) student Germain Tobar has been investigating the possibility of time travel, under the supervision of UQ physicist Dr. Fabio Costa.

"Classical dynamics says if you know the state of a system at a particular time, this can tell us the entire history of the system," Mr Tobar said.

"This has a wide range of applications, from allowing us to send rockets to other planets and modeling how fluids flow.

"For example, if I know the current position and velocity of an object falling under the force of gravity, I can calculate where it will be at any time.

"However, Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts the existence of time loops or time travel—where an event can be both in the past and future of itself—theoretically turning the study of dynamics on its head."

Mr Tobar said a unified theory that could reconcile both traditional dynamics and Einstein's Theory of Relativity was the holy grail of physics.

"But the current science says both theories cannot both be true," he said.

"As physicists, we want to understand the Universe's most basic, underlying laws and for years I've puzzled on how the science of dynamics can square with Einstein's predictions.

"I wondered: "is time travel mathematically possible?"

Mr Tobar and Dr. Costa say they have found a way to "square the numbers" and Dr. Costa said the calculations could have fascinating consequences for science.

"The maths checks out—and the results are the stuff of science fiction," Dr. Costa said.

"Say you traveled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus.

"However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected—that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place.

"This is a paradox—an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe.

"Some physicists say it is possible, but logically it's hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action.

"It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur."

However the researchers say their work shows that neither of these conditions have to be the case, and it is possible for events to adjust themselves to be logically consistent with any action that the time traveler makes.

"In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Mr Tobar said.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you.

"This would mean that—no matter your actions—the pandemic would occur, giving your younger self the motivation to go back and stop it.

"Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.

"The range of mathematical processes we discovered show that time travel with free will is logically possible in our universe without any paradox."

The research is published in Classical and Quantum Gravity .

Provided by University of Queensland

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Study reveals how humanity could unite to address global challenges

20 minutes ago

CO₂ worsens wildfires by helping plants grow, model experiments show

Surf clams off the coast of Virginia reappear and rebound

2 hours ago

Yellowstone Lake ice cover unchanged despite warming climate

3 hours ago

The history of the young cold traps of the asteroid Ceres

Researchers shine light on rapid changes in Arctic and boreal ecosystems

New benzofuran synthesis method enables complex molecule creation

Human odorant receptor for characteristic petrol note of Riesling wines identified

4 hours ago

Uranium-immobilizing bacteria in clay rock: Exploring how microorganisms can influence the behavior of radioactive waste

Research team identifies culprit behind canned wine's rotten egg smell

Relevant physicsforums posts, nasa is seeking a faster, cheaper way to bring mars samples to earth.

7 hours ago

Could you use the moon to reflect sunlight onto a solar sail?

Apr 14, 2024

Biot Savart law gives us magnetic field strength or magnetic flux density?

Why charge density of moving dipole is dependent on time.

Apr 5, 2024

I have a question about energy & ignoring friction losses

Apr 3, 2024

What Causes the Einstein - de Haas Effect in Iron Rods?

Mar 31, 2024

More from Other Physics Topics

Related Stories

How Einstein could help unlock the mysteries of space travel

Aug 21, 2015

Avengers: Endgame exploits time travel and quantum mechanics as it tries to restore the universe

Apr 25, 2019

Casimir force used to control and manipulate objects

Aug 4, 2020

Time travel is possible – but only if you have an object with infinite mass

Dec 13, 2018

Generalized Hardy's paradox shows an even stronger conflict between quantum and classical physics

Feb 1, 2018

Researcher uses math to investigate possibility of time travel

Apr 27, 2017

Recommended for you

Crucial connection for 'quantum internet' made for the first time

Physicists explain, and eliminate, unknown force dragging against water droplets on superhydrophobic surfaces

9 hours ago

CMS collaboration releases Higgs boson discovery data to the public

Study uses thermodynamics to describe expansion of the universe

Apr 15, 2024

Internet can achieve quantum speed with light saved as sound

Researchers control quantum properties of 2D materials with tailored light

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Skip to main content

- Agriculture + Food

- Arts + Society

- Business + Economy

- Engineering + Technology

- Environment + Sustainability

- Health + Medicine

- Resources + Energy

- Search news

- UQ responds

Young physicist ‘squares the numbers’ on time travel

Paradox-free time travel is theoretically possible, according to the mathematical modelling of a prodigious University of Queensland undergraduate student.

Fourth-year Bachelor of Advanced Science (Honours) student Germain Tobar has been investigating the possibility of time travel, under the supervision of UQ physicist Dr Fabio Costa .

“Classical dynamics says if you know the state of a system at a particular time, this can tell us the entire history of the system,” Mr Tobar said.

“This has a wide range of applications, from allowing us to send rockets to other planets and modelling how fluids flow.

“For example, if I know the current position and velocity of an object falling under the force of gravity, I can calculate where it will be at any time.

“However, Einstein's theory of general relativity predicts the existence of time loops or time travel – where an event can be both in the past and future of itself – theoretically turning the study of dynamics on its head.”

Mr Tobar said a unified theory that could reconcile both traditional dynamics and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity was the holy grail of physics.

“But the current science says both theories cannot both be true,” he said.

“As physicists, we want to understand the Universe’s most basic, underlying laws and for years I’ve puzzled on how the science of dynamics can square with Einstein’s predictions.

“I wondered: “is time travel mathematically possible?”

Mr Tobar and Dr Costa say they have found a way to “square the numbers” and Dr Costa said the calculations could have fascinating consequences for science.

“The maths checks out – and the results are the stuff of science fiction,” Dr Costa said.

“Say you travelled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19’s patient zero from being exposed to the virus.

“However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected – that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place.

“This is a paradox – an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe.

“Some physicists say it is possible, but logically it’s hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action.

“It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur.”

However the researchers say their work shows that neither of these conditions have to be the case, and it is possible for events to adjust themselves to be logically consistent with any action that the time traveller makes.

“In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would,” Mr Tobar said.

“No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you.

“This would mean that – no matter your actions - the pandemic would occur, giving your younger self the motivation to go back and stop it.

“Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.

“The range of mathematical processes we discovered show that time travel with free will is logically possible in our universe without any paradox.”

The research is published in Classical and Quantum Gravity (DOI: 10.1088/1361-6382/aba4bc ).

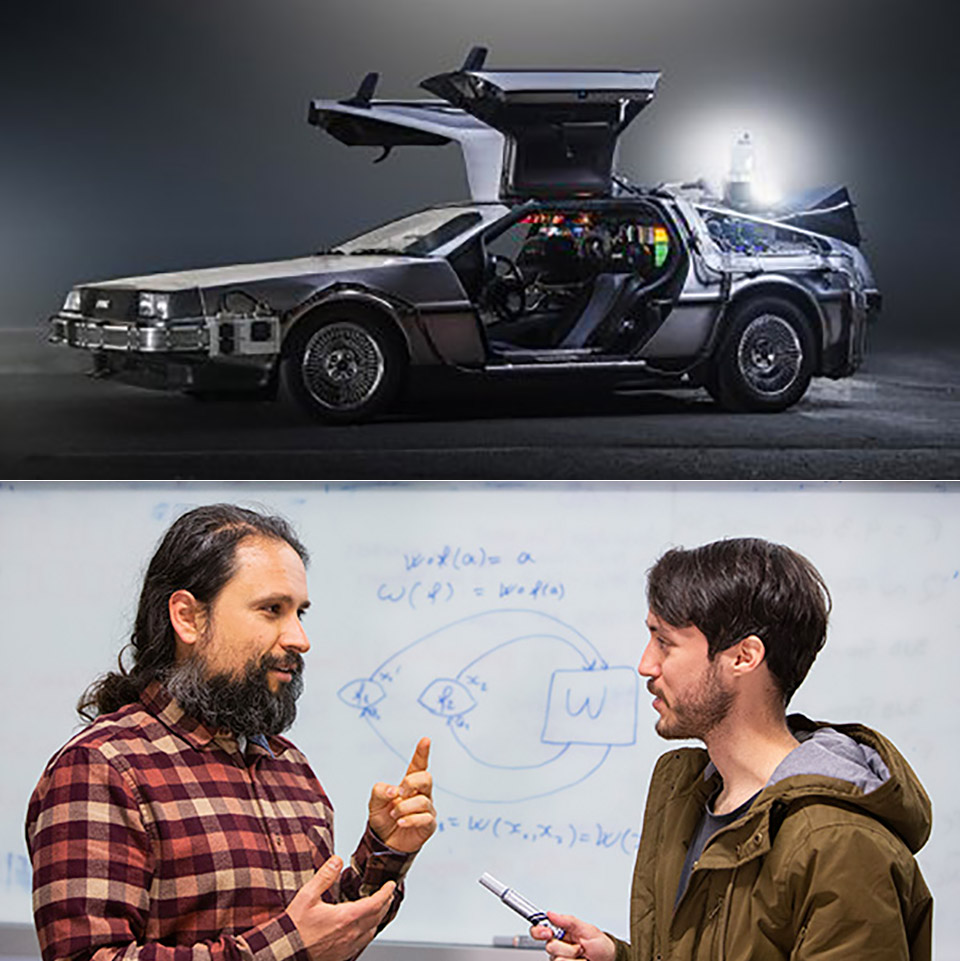

Image: Dr Fabio Costa (left) with Bachelor of Advanced Science (Honours) student Germain Tobar.

Media: Mr Germain Tobar, [email protected] , +61 406 123 686; Dr Fabio Costa, [email protected] , +61 456 646 231 ; Dominic Jarvis, [email protected] , +61 413 334 924.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Google Plus

Experts , Health + Medicine , Research

Environment + Sustainability , Science

Environment + Sustainability , Experts , Research

Research , Science

Engineering + Technology , Science

Agriculture + Food , Industry Collaboration , Research , Resources + Energy

Experts , Research , Science

Recent Headlines

- UQ celebrates 10 Advance Queensland Industry Research Fellowships 16 April 2024

- UQ leads subjects in QS World University Ranking 11 April 2024

The Conversation

Pharmacists should be able to dispense nicotine vapes without a prescription. here’s why, rideshare giant ola has abruptly exited the australian market. what does this mean for the future of ridesharing, australia now has a $70 ‘shadow price’ on carbon emissions. here’s why we won’t see a real price any time soon, el niño drought leaves zimbabwe’s lake kariba only 13% full: a disaster for people and wildlife, no, beetroot isn’t vegetable viagra. but here’s what else it can do.

+61 7 3365 1111

Other Campuses: UQ Gatton , UQ Herston

Maps and Directions

© 2024 The University of Queensland

A Member of

Privacy & Terms of use | Feedback

Authorised by: Director, Office of Marketing and Communications

ABN : 63 942 912 684 CRICOS Provider No: 00025B

Quick Links

- Emergency Contact

Social Media

- Giving to UQ

- Faculties & Divisions

- UQ Contacts

Ph. 3365 3333

- April 11, 2024 | Unlocking AI’s Black Box: New Formula Explains How They Detect Relevant Patterns

- April 11, 2024 | Sunflower Secrets Unveiled: Multiple Origins of Flower Symmetry Discovered

- April 11, 2024 | Unlocking Brain Health Through the Science of Nutrition

- April 11, 2024 | Improved Attention and Memory: Scientists Uncover New Cognitive Benefits of Video Games

- April 11, 2024 | Powering the Future: Unbiased PEC Cells Achieve Unprecedented Efficiency

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible: Physicist “Squares the Numbers” on Time Travel

By University of Queensland September 24, 2020

UQ physicists have been seeking to understand the time travel’s underlying laws. Credit: JMortonPhoto.com & OtoGodfrey.com

Paradox-free time travel is theoretically possible, according to the mathematical modeling of a prodigious University of Queensland (UQ) undergraduate student.

Fourth-year Bachelor of Advanced Science (Honours) student Germain Tobar has been investigating the possibility of time travel, under the supervision of UQ physicist Dr. Fabio Costa.

“Classical dynamics says if you know the state of a system at a particular time, this can tell us the entire history of the system,” Mr. Tobar said. “This has a wide range of applications, from allowing us to send rockets to other planets and modeling how fluids flow.

“For example, if I know the current position and velocity of an object falling under the force of gravity, I can calculate where it will be at any time.

“However, Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicts the existence of time loops or time travel – where an event can be both in the past and future of itself – theoretically turning the study of dynamics on its head.”

Mr. Tobar said a unified theory that could reconcile both traditional dynamics and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity was the holy grail of physics.

“But the current science says both theories cannot both be true,” he said. “As physicists, we want to understand the Universe’s most basic, underlying laws and for years I’ve been puzzled on how the science of dynamics can square with Einstein’s predictions.”

“I wondered is time travel mathematically possible?”

Mr. Tobar and Dr. Costa say they have found a way to “square the numbers” and Dr. Costa said the calculations could have fascinating consequences for science.

Dr. Fabio Costa (left) with Bachelor of Advanced Science (Honours) student Germain Tobar. Credit: Ho Vu

“The maths checks out – and the results are the stuff of science fiction,” Dr. Costa said.

“Say you traveled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19 ’s patient zero from being exposed to the virus . However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected – that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place.

“This is a paradox – an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe.

“Some physicists say it is possible, but logically it’s hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action. It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur.”

However, the researchers say their work shows that neither of these conditions has to be the case, and it is possible for events to adjust themselves to be logically consistent with any action that the time traveler makes.

“In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would,” Mr. Tobar said.

“No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you. This would mean that – no matter your actions – the pandemic would occur, giving your younger self the motivation to go back and stop it.

“Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.

“The range of mathematical processes we discovered show that time travel with free will is logically possible in our universe without any paradox.”

Reference: “Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice” by Germain Tobar and Fabio Costa, 21 September 2020, Classical and Quantum Gravity . DOI: 10.1088/1361-6382/aba4bc

More on SciTechDaily

Physicists Put Einstein to the Test With a Quantum-Mechanical Twin Paradox

Quantum Paradox Experiment Puts Einstein to the Test – May Lead to More Accurate Clocks and Sensors

Paradoxes of Probability & Statistical Strangeness

A Force From “Nothing” Used to Control and Manipulate Objects

New Quantum Paradox Reveals Contradiction Between Widely Held Beliefs – “Something’s Gotta Give”

“Obesity Paradox” Debunked in New Research

Peto’s Paradox – Biological Enigma Offers New Insights Into the Mystery of Cancer

Hawking’s Information Paradox: Resolving the Black Hole “Fuzzball or Wormhole” Debate

20 comments on "paradox-free time travel is theoretically possible: physicist “squares the numbers” on time travel".

“Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will ALWAYS adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.”

What if someone were to got back in time and kill their mother before she gave birth to him? How does that get ‘adjusted?’

You decide to go back and end Covid-19; it is Sept 24 2020: If you stopped “person-zero” from getting COVID-19, then “person-one” will get it in the “adjustment”. Back in Sept 24, 2020, COVID-19 is still around, and you still decide to go back to stop it. So then you are stopping “person-one”, and “person-two” gets the adjustment. Back in Sept 24, 2020, COVID-19 is still around, and you still decide to go back to stop it. So then you are stopping “person-two” and “person-three” gets the adjustment. So ….. you get trapped in an infinite time-loop from which you can never escape. OR this is a poorly written article in which (a) the author did not understand the mathematical model, or (b) the mathematicians did a poor job explaining what they are modeling, or (c) both, or (d) the MODEL is an incorrect model of the “real” universe, even though the “math” that describes the model is error free. Whatever the answer, this article left me with more questions than answers regarding the title of the article. WHAT?

I don’t think it’s neccessary to get trapped in endless loop. If I would like to try to stop the Patient-Zero from being infected by jumping back in time I would see the futility of the failed attempts and give up after a few loops. More over, jumping back-and-back-to-the-future-again should not cause memory erasure so all the trials would appear to me as a normal cause-effect chain from my perspective, so why should I try again and again? But now we know that timespace could be this self-correcting data stream and I should take this theory into consideration before I try to lose a chunk of >my< lifespan in the history. But that's just me trying to sound logical to myself 🙂

It seems that the poison made by Einstein continues toxicating physicists who blindly believe the current orthodox. They use general relativity as a tool to mathematically speculate the possibility of the existence of closed time curves in the so-called four-dimensional spacetime, but have never seriously defined what time travel really means. When they say somebody time travels to the past, which is the boundary of the person and his surroundings, and how do his surroundings continuously connect from the present to the past? Obviously, there is no way to have a logically consistent definition for so-called time travel.

It’s true that time scale is different for different physical processes. For example, a rabbit thinks that one year is a long time, but a turtle feels one year is just a blink. Some physical processes can even be reversed. Thus we define our physical time to be irreversible with a fixed scale as shown on a physical clock and use a rate to customize the description of the change of each physical process. For example, when a car has driven 100 km at a speed of 100 km/h, we know it takes one hour time, but then after it has driven for another 100 km backward at the same speed, we still think that the time it takes is another hour rather than a negative one hour because we consider the backward speed is negative, rather than time is negative. If somebody got healthier and looked younger after eating some special food, we would not think that time was reversed but just his aging rate was negative during the period. Reversible physical processes exist everywhere, but our physical time is always irreversible as we have defined.

Einstein made a fatal mistake in his special relativity. He assumed that the speed of light should be the same relative to all inertial reference frames, which requires the change of the definition of space and time. But he never verified that the newly defined time was still the time measured with physical clocks. Then many mathematicians and theoretical physicists think that time is like a playdough which can be made to fit all kinds of theories, while our physical time measured with physical clocks is stiff and absolute, which won’t change with the change of the definition of the space and time. Actually, the newly defined relativistic time is no longer the time measured with physical clocks, but just a mathematical variable without physical meanings, which can be easily verified as follows:

We know physical time T has a relationship with the relativistic time t in Einstein’s special relativity: T = tf/k where f is the relativistic frequency of the clock and k is a calibration constant. Now We would like to use the property of our physical time in Lorentz Transformation to verify that the relativistic time defined by Lorentz Transformation is no longer our physical time.

If you have a clock (clock 1) with you and watch my clock (clock 2) in motion and both clocks are set to be synchronized to show the same physical time T relative to your inertial reference frame, you will see your clock time: T1 = tf1/k1 = T and my clock time: T2 = tf2/k2 = T, where t is the relativistic time of your reference frame, f1 and f2 are the relativistic frequencies of clock 1 and clock 2 respectively, k1 and k2 are calibration constants of the clocks. The two events (Clock1, T1=T, x1=0, y1=0, z1=0, t1=t) and (Clock2, T2=T, x2=vt, y2=0, z2=0, t2=t) are simultaneous measured with both relativistic time t and clock time T in your reference frame. When these two clocks are observed by me in the moving inertial reference frame, according to special relativity, we can use Lorentz Transformation to get the events in my frame (x’, y’, z’, t’): (clock1, T1′, x1’=-vt1′, y1’=0, z1’=0, t1′) and (clock2, T2′, x2’=0, y2’=0, z2’=0, t2′), where T1′ = t1’f1’/k1 = (t/γ)(γf1)/k1 = tf1/k1 = T1 = T and T2′ = t2’f2’/k2 = (γt)(f2/γ)/k2 = tf2/k2 = T2 = T, where γ = 1/sqrt(1-v^2/c^2). That is, no matter observed from which inertial reference frame, the events are still simultaneous measured with physical time T i.e. the two clocks are always synchronized measured with physical time T, but not synchronized measured with relativistic time t’. Therefore, our physical time and the relativistic time behave differently in Lorentz Transformation and thus they are not the same thing. The change of the reference frame only makes changes of the relativistic time from t to t’ and the relativistic frequency from f to f’, which cancel each other in the formula: T = tf/k to make the physical time T unchanged i.e. our physical time is still absolute in special relativity. Therefore, based on the artificial relativistic time, special relativity is wrong, so is general relativity. For more details, please check: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297527784_Challenge_to_the_Special_Theory_of_Relativity

Once we know our physical time is absolute, there is no room for those mathematicians and theoretical physicists to speculate.

I find it disconcerting that space is never discussed while musing over time travel. The arrow of time moves with space, forward. To travel back in time, one would also need to move in space. So, you may go back in time (if you had a sci-fi apparatus), but, the rest of the universe would proceed on its merry way. Thus, you and your apparatus, going back in time one hour would find that you are out drifting in space because the earth and the rest of the universe continues on it way. Time and space do not readily part ways to accommodate a fantasy. There are probably more profitable areas of conjecture for intelligent students, professors and scientists to spend their time.

And because time travel implicitly requires space travel, the amount of energy required becomes mind boggling. Also, because there is a finite limit on the speed of any material object, it means that one can’t go back in time instantaneously. It would require a very long time to move to the position in space occupied by Earth 100 million years ago, even at the speed of light. And, the calculations would have to be unobtainably accurate or one might end up outside the atmosphere, or in the interior of the Earth.

Perhaps we should be changing the name of the website from “Sci-Tech Daily” to “Sci-Assume Daily”?

You fail no matter what you do. It could turn out that it wasn’t really your mother but a lookalike. Or that you hallucinated it, which wouldn’t be far fetched for someone seriously trying to kill their mother.

So this is still wrong. The events wouldn’t “shift” to prevent the paradox. There IS no paradox. You did it because in your timeline the events happened. But in doing so, youve created a timeline where they didn’t. There is no need for your younger self to go back, but you did. This isn’t a paradox, it’s a different timeline. You crated a branch in the timeline. An alternate universe.

What evidence do you have that alternate universes exist?

… Yeah, “Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible” … it doesn’t mean that we actually have a time travel, or that some advanced civilization has developed a time travel, after all… So! The next idea it might be that aliens are the humans from the future! Yeah, that is a great idea, a really great one…

The act of time traveling is a paradox within itself. It has to happen in the greater time line for everything afterwards to occur. Also, the Russians already achieved a six minute time travel a decade ago…

… “I wondered: “is time travel mathematically possible?”

Well, we all have asked our self the very same question. However, we have no evidence of such a thing happening, or ever happened. Though, it would be great. Second thing is that time dilatation, which has been proven correct, but was it perceived in a proper way, or it is just the numbers that mean something else. …

According to current physical theory, is it possible for a human being to travel through time?

… ask Goedel, he would know about paradoxes that might arise from theory of relativity…

It would correct itself if you tried to kill your mother by someone stopping you from doing it or you leave thinking your mother is dead but isn’t or even that you’re giving birth to buy a different woman. And this time travel thing kind of plays along in the theory that our universe is actually the interior of a black hole just inside the horizon. A wormhole would be like getting right to the edge of the horizon and then it bending you back around to a point in the past as you try to cross it. Which kind of goes along with the fact that if you tried to travel in a straight line away from the Earth fast enough for long enough you would get back to the Earth except if the speed is fast enough you would get back to the Earth in the future though you would not have aged. But anyway going back in the past and killing your mother would be made impossible by whatever happened to stop you from killing her. Moreover you would never even be allowed to meet her at least not where she’s aware that it’s you because that would change the future. So impossible to kill your mother in the past no matter how hard you tried. And people like to say well if sometime people invent time travel to the past why haven’t they come back and talk to us. Maybe it’s impossible because of time correcting itself. Or if creating a paradox is possible people of the future realize that they could wipe themselves out and interference with the past is not something they do. They only observe. Maybe even have rules for exactly when they’re allowed to go to. Maybe they’re only allowed to travel to prehistory. Not travel to somewhere where it could cause a paradox just by knowing someone’s from the future.

All of these comments are interesting and informative.

But they all assume a past Paradigm that only Time Moves. We are holding onto a rock in the river of Time as the current flows past us from the Past through the Present and into the Future.

We are not holding onto the rock of Earth as the Sun, planets, stars and galaxies flow around us. We move through moving Space.

ALL OF THESE VIEWS also assume we can change Time with our actions. WE NEVER CHANGE TIME WITH OUR ACTIONS. WE CHANGE OUR JOURNEY THROUGH TIME WITH OUR ACTIONS. (Drop your egocentric notions.)

We move through moving spacetime.

A Paradigm Shift from geocentric to heliocentric helped explain our neighboring space.

A Paradigm Shift from Newton to Einstein helped explain our neighboring spacetime.

Publishing my spacetime / mattergy Paradigm Shift Work will solve all your Paradoxes.

Time travel could very well be possible in this day and age. But it may be a whole lot slower than people would imagine.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qCEwPT80cSA

I’ve been travelling forward in time for sixty years.

Time travel? The paradox that these two words conjure in one’s analytical mind are endless. No two people imagine what these words mean in the same way. Some believe only a single body jumps through time with all the cognitive capabilities and memories of another time left in tact. Where others imagine the time travelers mind and memories also change to synchronize with the time visited. Does this insinuation limit time travel for someone to the number of years they have been alive? And does the visitation of a time where the traveler was an infant subject that person to a life of Deja-Vu episodes? Does the number of times one has time traveled have a direct correlation with an elevated intelligence to reasoning capability? If so, would that be a reason to assume an increased intellectual capability of anyone who leaps through time to visit our planet. And No, the mere virtue of them having the technology to travel in that method does not imply they must understand how it works. Look how many use modern conveniences regularly with no clue as to their engineering. Everything a person does in this modern society is by the grace of someone else’s knowledge and occupation. My guess is that if time travel is possible, the ancillary effects of doing so would be unavoidable. Nothing in this universe has only positive result. For every action does have an equal and opposite reaction. My luck I would leap to a time in the future, and find its one day after my burial. Oh Chit!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Email address is optional. If provided, your email will not be published or shared.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Arabica Coffee Originated More Than 600,000 Years Ago in Ethiopia: Study

- Surprisingly Massive Stellar-Mass Black Hole Detected in Nearby Binary System

- 8,600-Year-Old Bread Found in Türkiye

- New Titanosaur Species Identified in Argentina

- Study: Just Like Homo sapiens, Neanderthals Organized Their Living Space in Structured Way

- Dietary Fiber Consumption Reduces Blood Pressure, Prevents Cardiovascular Disease, Review Says

- Astronomers Detect Unusual Radio Pulses from Nearby Magnetar

Paradox-Free Time Travel is Mathematically Possible: Study

Time travel with free will is logically possible in our Universe without any paradox, according to new research from the University of Queensland.

Physicists seek to understand the underlying laws of the Universe. Image credit: Johnson Martin.

“Classical dynamics says if you know the state of a system at a particular time, this can tell us the entire history of the system,” said Germain Tobar , a student in the School of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Queensland.

“This has a wide range of applications, from allowing us to send rockets to other planets and modeling how fluids flow.”

“For example, if I know the current position and velocity of an object falling under the force of gravity, I can calculate where it will be at any time.”

“However, Einstein’s theory of general relativity predicts the existence of time loops or time travel — where an event can be both in the past and future of itself — theoretically turning the study of dynamics on its head.”

A unified theory that could reconcile both traditional dynamics and Einstein’s theory of relativity is the holy grail of physics.

“But the current science says both theories cannot both be true,” Tobar said.

“As physicists, we want to understand the Universe’s most basic, underlying laws and for years I’ve puzzled on how the science of dynamics can square with Einstein’s predictions.”

“I wondered: Is time travel mathematically possible?”

Tobar and his colleague, Dr. Fabio Costa from the Centre for Engineered Quantum Systems in the School of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Queensland, found a way to ‘square the numbers’ and their calculations could have fascinating consequences for science.

“The maths checks out — and the results are the stuff of science fiction,” Dr. Costa said.

“Say you traveled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19’s patient zero from being exposed to the virus.”

“However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected — that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place.”

“This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our Universe.”

“Some physicists say it is possible, but logically it’s hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action.”

“It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur.”

The team’s work shows that neither of these conditions has to be the case, and it is possible for events to adjust themselves to be logically consistent with any action that the time traveler makes.

The study was published in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity .

Germain Tobar & Fabio Costa. 2020. Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice. Class. Quantum Grav 37: 205011; doi: 10.1088/1361-6382/aba4bc

This article is based on text provided by the University of Queensland.

Physicists Find Evidence of New Subatomic Particle

CERN Physicists Measure Width of W Boson

Scientists Discuss Physics and Mathematics behind ‘3 Body Problem’

CERN Physicists Measure High-Energy Neutrino Interaction Strength

Scientists Discover ‘Neutronic Molecules’

CERN Physicists Measure One of Key Parameters of Standard Model

Dark Matter Capture and Annihilation Can Heat Old, Isolated Neutron Stars, Physicists Say

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible, Researchers Say

Matthew S. Schwartz

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered. Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

A dog dressed as Marty McFly from Back to the Future attends the Tompkins Square Halloween Dog Parade in 2015. New research says time travel might be possible without the problems McFly encountered.

"The past is obdurate," Stephen King wrote in his book about a man who goes back in time to prevent the Kennedy assassination. "It doesn't want to be changed."

Turns out, King might have been on to something.

Countless science fiction tales have explored the paradox of what would happen if you went back in time and did something in the past that endangered the future. Perhaps one of the most famous pop culture examples is in Back to the Future , when Marty McFly goes back in time and accidentally stops his parents from meeting, putting his own existence in jeopardy.

But maybe McFly wasn't in much danger after all. According a new paper from researchers at the University of Queensland, even if time travel were possible, the paradox couldn't actually exist.

Researchers ran the numbers and determined that even if you made a change in the past, the timeline would essentially self-correct, ensuring that whatever happened to send you back in time would still happen.

"Say you traveled in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus," University of Queensland scientist Fabio Costa told the university's news service .

"However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place," said Costa, who co-authored the paper with honors undergraduate student Germain Tobar.

"This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe."

A variation is known as the "grandfather paradox" — in which a time traveler kills their own grandfather, in the process preventing the time traveler's birth.

The logical paradox has given researchers a headache, in part because according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, "closed timelike curves" are possible, theoretically allowing an observer to travel back in time and interact with their past self — potentially endangering their own existence.

But these researchers say that such a paradox wouldn't necessarily exist, because events would adjust themselves.

Take the coronavirus patient zero example. "You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so, you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar told the university's news service.

In other words, a time traveler could make changes, but the original outcome would still find a way to happen — maybe not the same way it happened in the first timeline but close enough so that the time traveler would still exist and would still be motivated to go back in time.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you," Tobar said.

The paper, "Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice," was published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity . The findings seem consistent with another time travel study published this summer in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review Letters. That study found that changes made in the past won't drastically alter the future.

Bestselling science fiction author Blake Crouch, who has written extensively about time travel, said the new study seems to support what certain time travel tropes have posited all along.

"The universe is deterministic and attempts to alter Past Event X are destined to be the forces which bring Past Event X into being," Crouch told NPR via email. "So the future can affect the past. Or maybe time is just an illusion. But I guess it's cool that the math checks out."

- grandfather paradox

- time travel

UQ physics student works out ‘paradox-free’ time travel

An Aussie physics student says he has proven how “paradox-free” time travel is possible – but it couldn’t be used to prevent COVID-19.

‘Crying’: Family’s emotional Molly update

Three new kangaroo species uncovered

Molly the magpie reunited with best friend

A young University of Queensland student says he has found a way to “square the numbers” and prove that “paradox-free” time travel is theoretically possible in our universe.

From Back To The Future to Terminator to 12 Monkeys , stories dealing with time travel invariably have had to grapple with an age-old head-scratcher.

The so-called “grandfather paradox” – that a time traveller could kill their grandparent, preventing their own birth – broadly describes the logical inconsistency that arises from any action that would change the past.

But Germain Tobar, a fourth-year Bachelor of Advanced Science student, believes he has solved the riddle.

“Classical dynamics says if you know the state of a system at a particular time, this can tell us the entire history of the system,” he said in a statement.

“This has a wide range of applications, from allowing us to send rockets to other planets and modelling how fluids flow. For example, if I know the current position and velocity of an object falling under the force of gravity, I can calculate where it will be at any time.”

Einstein’s theory of general relativity, however, predicts the existence of time loops or time travel, “where an event can be both in the past and future of itself – theoretically turning the study of dynamics on its head”.

Mr Tobar said a unified theory that could reconcile both traditional dynamics and Einstein’s theory of relativity was the holy grail of physics.

“But the current science says both theories cannot both be true,” he said.

“As physicists, we want to understand the universe’s most basic, underlying laws and for years I’ve puzzled on how the science of dynamics can square with Einstein’s predictions. I wondered, ‘Is time travel mathematically possible?’”

Mr Tobar and his supervisor, UQ physicist Dr Fabio Costa, say they have found a way to “square the numbers” – and that the findings have fascinating consequences for science.

“The maths checks out – and the results are the stuff of science fiction,” Dr Costa said.

Dr Costa gives the example of travelling in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19’s “patient zero” being exposed to the virus.

As the grandfather paradox shows, if you stopped that individual getting infected, “that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place”.

“This is a paradox – an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe,” he said.

“Some physicists say it is possible, but logically it’s hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action. It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur.”

But the researchers, whose findings appear in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity , say their mathematical modelling shows that neither of these conditions have to be the case.

Instead, they show it is possible for events to adjust themselves to be logically consistent with any action that the time traveller makes.

“In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would,” Mr Tobar said.

“No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you. This would mean that – no matter your actions – the pandemic would occur, giving your younger self the motivation to go back and stop it.”

He added, “Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency. The range of mathematical processes we discovered show that time travel with free will is logically possible in our universe without any paradox.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Instagram-famous magpie Molly the magpie has been pictured reunited with his Staffy friends and human carers after a 45-day seizure.

Three new species of extinct kangaroo have been described for the first time — including one that grew about twice the size of their living relatives.

After a tumultuous 45 days in the custody of authorities, Molly the magpie has finally been reunited with its unlikely canine companion.

Paradox-Free Time Travel Proven Possible by Physics Student

I think this kid just earned himself an a+..

The rules of time-travel have been debated by scientists and sci-fi fans alike for years, but now a student physicist has been able to "square the numbers" to show how paradox-free time travel is theoretically possible. This means that should someone be able to time travel, the dreaded butterfly effect might not be as inevitable as has been feared -- but that doesn't mean a time-traveler might not still face unintended consequences.

In a peer-reviewed paper published in Classical and Quantum Gravity , University of Queensland student, Germain Tobar, collaborating with the university's physics professor Fabio Costa, mathematically discovered how, " time travel with free will is logically possible in our universe without any paradox.”

The math involved in all this is enough to make Will Hunting scratch his head but Tobar, like a different Matt Damon character, has been able to "science the shit" out of theorizing how one could travel through time without causing those pesky logical paradoxes that bedevil many a science-fiction protagonist.

One such example is the so-called grandfather paradox wherein, as their paper puts it, "a time traveller could kill her own grandfather and thus prevent her own birth, leading to a logical inconsistency." Or, someone going back in time to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic from happening would then nix the very reason why they ever traveled through time. Yes, it's like those arguments about time travel in Avengers: Endgame all over again!

“This is a paradox – an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe," Costa said. "Some physicists say it is possible, but logically it’s hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action. It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur.”

Tobar basically said, hold my beer and went about proving that, theoretically, one can travel through time, exert free will, and not create any such logical paradoxes.

Or, as Popular Mechanics succinctly puts it, "as long as just two pieces of an entire scenario within a CTC are still in 'causal order' when you leave, the rest is subject to local free will."

Tobar's calculations show how theoretically one could time-travel and exert free will in a way that wouldn't prevent the reason why they went back in time. But it could make them wish they had never time-traveled to begin with:

For more science coverage, learn about the possibility of life on Venus , evidence of a parallel universe where time runs backward , why the moon is rusting , and the discovery of underground lakes on Mars .

Why You Should Always Play Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy VIII Back to Back

Experience Gaming Excellence with the SteelSeries Apex Pro Mechanical Gaming Keyboard

Lego Unleashes the Dragon in Their Incredible 2024 Lunar New Year Sets

Enter the World of Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora – A Thrilling Gameplay Preview

Can we time travel? A theoretical physicist provides some answers

Emeritus professor, Physics, Carleton University

Disclosure statement

Peter Watson received funding from NSERC. He is affiliated with Carleton University and a member of the Canadian Association of Physicists.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Carleton University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

Time travel makes regular appearances in popular culture, with innumerable time travel storylines in movies, television and literature. But it is a surprisingly old idea: one can argue that the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex , written by Sophocles over 2,500 years ago, is the first time travel story .

But is time travel in fact possible? Given the popularity of the concept, this is a legitimate question. As a theoretical physicist, I find that there are several possible answers to this question, not all of which are contradictory.

The simplest answer is that time travel cannot be possible because if it was, we would already be doing it. One can argue that it is forbidden by the laws of physics, like the second law of thermodynamics or relativity . There are also technical challenges: it might be possible but would involve vast amounts of energy.

There is also the matter of time-travel paradoxes; we can — hypothetically — resolve these if free will is an illusion, if many worlds exist or if the past can only be witnessed but not experienced. Perhaps time travel is impossible simply because time must flow in a linear manner and we have no control over it, or perhaps time is an illusion and time travel is irrelevant.

Laws of physics

Since Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity — which describes the nature of time, space and gravity — is our most profound theory of time, we would like to think that time travel is forbidden by relativity. Unfortunately, one of his colleagues from the Institute for Advanced Study, Kurt Gödel, invented a universe in which time travel was not just possible, but the past and future were inextricably tangled.

We can actually design time machines , but most of these (in principle) successful proposals require negative energy , or negative mass, which does not seem to exist in our universe. If you drop a tennis ball of negative mass, it will fall upwards. This argument is rather unsatisfactory, since it explains why we cannot time travel in practice only by involving another idea — that of negative energy or mass — that we do not really understand.

Mathematical physicist Frank Tipler conceptualized a time machine that does not involve negative mass, but requires more energy than exists in the universe .

Time travel also violates the second law of thermodynamics , which states that entropy or randomness must always increase. Time can only move in one direction — in other words, you cannot unscramble an egg. More specifically, by travelling into the past we are going from now (a high entropy state) into the past, which must have lower entropy.

This argument originated with the English cosmologist Arthur Eddington , and is at best incomplete. Perhaps it stops you travelling into the past, but it says nothing about time travel into the future. In practice, it is just as hard for me to travel to next Thursday as it is to travel to last Thursday.

Resolving paradoxes

There is no doubt that if we could time travel freely, we run into the paradoxes. The best known is the “ grandfather paradox ”: one could hypothetically use a time machine to travel to the past and murder their grandfather before their father’s conception, thereby eliminating the possibility of their own birth. Logically, you cannot both exist and not exist.

Read more: Time travel could be possible, but only with parallel timelines

Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five , published in 1969, describes how to evade the grandfather paradox. If free will simply does not exist, it is not possible to kill one’s grandfather in the past, since he was not killed in the past. The novel’s protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, can only travel to other points on his world line (the timeline he exists in), but not to any other point in space-time, so he could not even contemplate killing his grandfather.

The universe in Slaughterhouse-Five is consistent with everything we know. The second law of thermodynamics works perfectly well within it and there is no conflict with relativity. But it is inconsistent with some things we believe in, like free will — you can observe the past, like watching a movie, but you cannot interfere with the actions of people in it.

Could we allow for actual modifications of the past, so that we could go back and murder our grandfather — or Hitler ? There are several multiverse theories that suppose that there are many timelines for different universes. This is also an old idea: in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol , Ebeneezer Scrooge experiences two alternative timelines, one of which leads to a shameful death and the other to happiness.

Time is a river

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius wrote that:

“ Time is like a river made up of the events which happen , and a violent stream; for as soon as a thing has been seen, it is carried away, and another comes in its place, and this will be carried away too.”

We can imagine that time does flow past every point in the universe, like a river around a rock. But it is difficult to make the idea precise. A flow is a rate of change — the flow of a river is the amount of water that passes a specific length in a given time. Hence if time is a flow, it is at the rate of one second per second, which is not a very useful insight.

Theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking suggested that a “ chronology protection conjecture ” must exist, an as-yet-unknown physical principle that forbids time travel. Hawking’s concept originates from the idea that we cannot know what goes on inside a black hole, because we cannot get information out of it. But this argument is redundant: we cannot time travel because we cannot time travel!

Researchers are investigating a more fundamental theory, where time and space “emerge” from something else. This is referred to as quantum gravity , but unfortunately it does not exist yet.

So is time travel possible? Probably not, but we don’t know for sure!

- Time travel

- Stephen Hawking

- Albert Einstein

- Listen to this article

- Time travel paradox

- Arthur Eddington

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Technical Skills Laboratory Officer

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Physicist Devises Mathematical Theory to Prove that Paradox-Free Time Travel is Possible

- Head Back to the Future in the iconic, time-traveling DeLorean!

- Complete with working lights and the must-have flux capacitor, the DeLorean is ready to go once Dr. Emmett Brown arrives with the plutonium cores!

- Then the action begins as Marty McFly and the good doctor travel back in time, along with trusty old Einstein. The duo is sporting their 1985 outfits

Classical dynamics says if you know the state of a system at a particular time, this can tell us the entire history of the system. The range of mathematical processes we discovered show that time travel with free will is logically possible in our universe without any paradox,” said Tobar.

Related Posts

A technology, gadget and video game enthusiast that loves covering the latest industry news. Favorite trade show? Mobile World Congress in Barcelona.

Mortal Kombat 2 Source Code Leaked Online, Reveals Never Before Seen Animations

Saturn’s Icy Moon Enceladus Could Harbor Life in One of its Water Jets

Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Theoretically Possible, Researchers Say

"The past is obdurate," Stephen King wrote in his book about a man who goes back in time to prevent the Kennedy assassination. "It doesn't want to be changed."

Turns out, King might have been on to something.

Countless science fiction tales have explored the paradox of what would happen if you went back in time and did something in the past that endangered the future. Perhaps one of the most famous pop culture examples is in Back to the Future , when Marty McFly goes back in time and accidentally stops his parents from meeting, putting his own existence in jeopardy.

But maybe McFly wasn't in much danger after all. According a new paper from researchers at the University of Queensland, even if time travel were possible, the paradox couldn't actually exist.

Researchers ran the numbers and determined that even if you made a change in the past, the timeline would essentially self-correct, ensuring that whatever happened to send you back in time would still happen.

"Say you traveled in time in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus," University of Queensland scientist Fabio Costa told the university's news service .

"However, if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place," said Costa, who co-authored the paper with honors undergraduate student Germain Tobar.

"This is a paradox — an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe."

A variation is known as the "grandfather paradox" — in which a time traveler kills their own grandfather, in the process preventing the time traveler's birth.

The logical paradox has given researchers a headache, in part because according to Einstein's theory of general relativity, "closed timelike curves" are possible, theoretically allowing an observer to travel back in time and interact with their past self — potentially endangering their own existence.

But these researchers say that such a paradox wouldn't necessarily exist, because events would adjust themselves.

Take the coronavirus patient zero example. "You might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so, you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would," Tobar told the university's news service.

In other words, a time traveler could make changes, but the original outcome would still find a way to happen — maybe not the same way it happened in the first timeline but close enough so that the time traveler would still exist and would still be motivated to go back in time.

"No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you," Tobar said.

The paper, "Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice," was published last week in the peer-reviewed journal Classical and Quantum Gravity . The findings seem consistent with another time travel study published this summer in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review Letters. That study found that changes made in the past won't drastically alter the future.

Bestselling science fiction author Blake Crouch, who has written extensively about time travel, said the new study seems to support what certain time travel tropes have posited all along.

"The universe is deterministic and attempts to alter Past Event X are destined to be the forces which bring Past Event X into being," Crouch told NPR via email. "So the future can affect the past. Or maybe time is just an illusion. But I guess it's cool that the math checks out."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Time Travel

There is an extensive literature on time travel in both philosophy and physics. Part of the great interest of the topic stems from the fact that reasons have been given both for thinking that time travel is physically possible—and for thinking that it is logically impossible! This entry deals primarily with philosophical issues; issues related to the physics of time travel are covered in the separate entries on time travel and modern physics and time machines . We begin with the definitional question: what is time travel? We then turn to the major objection to the possibility of backwards time travel: the Grandfather paradox. Next, issues concerning causation are discussed—and then, issues in the metaphysics of time and change. We end with a discussion of the question why, if backwards time travel will ever occur, we have not been visited by time travellers from the future.

1.1 Time Discrepancy

1.2 changing the past, 2.1 can and cannot, 2.2 improbable coincidences, 2.3 inexplicable occurrences, 3.1 backwards causation, 3.2 causal loops, 4.1 time travel and time, 4.2 time travel and change, 5. where are the time travellers, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is time travel.

There is a number of rather different scenarios which would seem, intuitively, to count as ‘time travel’—and a number of scenarios which, while sharing certain features with some of the time travel cases, seem nevertheless not to count as genuine time travel: [ 1 ]

Time travel Doctor . Doctor Who steps into a machine in 2024. Observers outside the machine see it disappear. Inside the machine, time seems to Doctor Who to pass for ten minutes. Observers in 1984 (or 3072) see the machine appear out of nowhere. Doctor Who steps out. [ 2 ] Leap . The time traveller takes hold of a special device (or steps into a machine) and suddenly disappears; she appears at an earlier (or later) time. Unlike in Doctor , the time traveller experiences no lapse of time between her departure and arrival: from her point of view, she instantaneously appears at the destination time. [ 3 ] Putnam . Oscar Smith steps into a machine in 2024. From his point of view, things proceed much as in Doctor : time seems to Oscar Smith to pass for a while; then he steps out in 1984. For observers outside the machine, things proceed differently. Observers of Oscar’s arrival in the past see a time machine suddenly appear out of nowhere and immediately divide into two copies of itself: Oscar Smith steps out of one; and (through the window) they see inside the other something that looks just like what they would see if a film of Oscar Smith were played backwards (his hair gets shorter; food comes out of his mouth and goes back into his lunch box in a pristine, uneaten state; etc.). Observers of Oscar’s departure from the future do not simply see his time machine disappear after he gets into it: they see it collide with the apparently backwards-running machine just described, in such a way that both are simultaneously annihilated. [ 4 ] Gödel . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship (not a special time machine) and flies off on a certain course. At no point does she disappear (as in Leap ) or ‘turn back in time’ (as in Putnam )—yet thanks to the overall structure of spacetime (as conceived in the General Theory of Relativity), the traveller arrives at a point in the past (or future) of her departure. (Compare the way in which someone can travel continuously westwards, and arrive to the east of her departure point, thanks to the overall curved structure of the surface of the earth.) [ 5 ] Einstein . The time traveller steps into an ordinary rocket ship and flies off at high speed on a round trip. When he returns to Earth, thanks to certain effects predicted by the Special Theory of Relativity, only a very small amount of time has elapsed for him—he has aged only a few months—while a great deal of time has passed on Earth: it is now hundreds of years in the future of his time of departure. [ 6 ] Not time travel Sleep . One is very tired, and falls into a deep sleep. When one awakes twelve hours later, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Coma . One is in a coma for a number of years and then awakes, at which point it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Cryogenics . One is cryogenically frozen for hundreds of years. Upon being woken, it seems from one’s own point of view that hardly any time has passed. Virtual . One enters a highly realistic, interactive virtual reality simulator in which some past era has been recreated down to the finest detail. Crystal . One looks into a crystal ball and sees what happened at some past time, or will happen at some future time. (Imagine that the crystal ball really works—like a closed-circuit security monitor, except that the vision genuinely comes from some past or future time. Even so, the person looking at the crystal ball is not thereby a time traveller.) Waiting . One enters one’s closet and stays there for seven hours. When one emerges, one has ‘arrived’ seven hours in the future of one’s ‘departure’. Dateline . One departs at 8pm on Monday, flies for fourteen hours, and arrives at 10pm on Monday.

A satisfactory definition of time travel would, at least, need to classify the cases in the right way. There might be some surprises—perhaps, on the best definition of ‘time travel’, Cryogenics turns out to be time travel after all—but it should certainly be the case, for example, that Gödel counts as time travel and that Sleep and Waiting do not. [ 7 ]

In fact there is no entirely satisfactory definition of ‘time travel’ in the literature. The most popular definition is the one given by Lewis (1976, 145–6):

What is time travel? Inevitably, it involves a discrepancy between time and time. Any traveller departs and then arrives at his destination; the time elapsed from departure to arrival…is the duration of the journey. But if he is a time traveller, the separation in time between departure and arrival does not equal the duration of his journey.…How can it be that the same two events, his departure and his arrival, are separated by two unequal amounts of time?…I reply by distinguishing time itself, external time as I shall also call it, from the personal time of a particular time traveller: roughly, that which is measured by his wristwatch. His journey takes an hour of his personal time, let us say…But the arrival is more than an hour after the departure in external time, if he travels toward the future; or the arrival is before the departure in external time…if he travels toward the past.

This correctly excludes Waiting —where the length of the ‘journey’ precisely matches the separation between ‘arrival’ and ‘departure’—and Crystal , where there is no journey at all—and it includes Doctor . It has trouble with Gödel , however—because when the overall structure of spacetime is as twisted as it is in the sort of case Gödel imagined, the notion of external time (“time itself”) loses its grip.

Another definition of time travel that one sometimes encounters in the literature (Arntzenius, 2006, 602) (Smeenk and Wüthrich, 2011, 5, 26) equates time travel with the existence of CTC’s: closed timelike curves. A curve in this context is a line in spacetime; it is timelike if it could represent the career of a material object; and it is closed if it returns to its starting point (i.e. in spacetime—not merely in space). This now includes Gödel —but it excludes Einstein .

The lack of an adequate definition of ‘time travel’ does not matter for our purposes here. [ 8 ] It suffices that we have clear cases of (what would count as) time travel—and that these cases give rise to all the problems that we shall wish to discuss.

Some authors (in philosophy, physics and science fiction) consider ‘time travel’ scenarios in which there are two temporal dimensions (e.g. Meiland (1974)), and others consider scenarios in which there are multiple ‘parallel’ universes—each one with its own four-dimensional spacetime (e.g. Deutsch and Lockwood (1994)). There is a question whether travelling to another version of 2001 (i.e. not the very same version one experienced in the past)—a version at a different point on the second time dimension, or in a different parallel universe—is really time travel, or whether it is more akin to Virtual . In any case, this kind of scenario does not give rise to many of the problems thrown up by the idea of travelling to the very same past one experienced in one’s younger days. It is these problems that form the primary focus of the present entry, and so we shall not have much to say about other kinds of ‘time travel’ scenario in what follows.

One objection to the possibility of time travel flows directly from attempts to define it in anything like Lewis’s way. The worry is that because time travel involves “a discrepancy between time and time”, time travel scenarios are simply incoherent. The time traveller traverses thirty years in one year; she is 51 years old 21 years after her birth; she dies at the age of 100, 200 years before her birth; and so on. The objection is that these are straightforward contradictions: the basic description of what time travel involves is inconsistent; therefore time travel is logically impossible. [ 9 ]

There must be something wrong with this objection, because it would show Einstein to be logically impossible—whereas this sort of future-directed time travel has actually been observed (albeit on a much smaller scale—but that does not affect the present point) (Hafele and Keating, 1972b,a). The most common response to the objection is that there is no contradiction because the interval of time traversed by the time traveller and the duration of her journey are measured with respect to different frames of reference: there is thus no reason why they should coincide. A similar point applies to the discrepancy between the time elapsed since the time traveller’s birth and her age upon arrival. There is no more of a contradiction here than in the fact that Melbourne is both 800 kilometres away from Sydney—along the main highway—and 1200 kilometres away—along the coast road. [ 10 ]

Before leaving the question ‘What is time travel?’ we should note the crucial distinction between changing the past and participating in (aka affecting or influencing) the past. [ 11 ] In the popular imagination, backwards time travel would allow one to change the past: to right the wrongs of history, to prevent one’s younger self doing things one later regretted, and so on. In a model with a single past, however, this idea is incoherent: the very description of the case involves a contradiction (e.g. the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976, and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976). It is not as if there are two versions of the past: the original one, without the time traveller present, and then a second version, with the time traveller playing a role. There is just one past—and two perspectives on it: the perspective of the younger self, and the perspective of the older time travelling self. If these perspectives are inconsistent (e.g. an event occurs in one but not the other) then the time travel scenario is incoherent.

This means that time travellers can do less than we might have hoped: they cannot right the wrongs of history; they cannot even stir a speck of dust on a certain day in the past if, on that day, the speck was in fact unmoved. But this does not mean that time travellers must be entirely powerless in the past: while they cannot do anything that did not actually happen, they can (in principle) do anything that did happen. Time travellers cannot change the past: they cannot make it different from the way it was—but they can participate in it: they can be amongst the people who did make the past the way it was. [ 12 ]

What about models involving two temporal dimensions, or parallel universes—do they allow for coherent scenarios in which the past is changed? [ 13 ] There is certainly no contradiction in saying that the time traveller burns all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 1 (or at hypertime A ), and does not burn all her diaries at midnight on her fortieth birthday in 1976 in universe 2 (or at hypertime B ). The question is whether this kind of story involves changing the past in the sense originally envisaged: righting the wrongs of history, preventing subsequently regretted actions, and so on. Goddu (2003) and van Inwagen (2010) argue that it does (in the context of particular hypertime models), while Smith (1997, 365–6; 2015) argues that it does not: that it involves avoiding the past—leaving it untouched while travelling to a different version of the past in which things proceed differently.

2. The Grandfather Paradox

The most important objection to the logical possibility of backwards time travel is the so-called Grandfather paradox. This paradox has actually convinced many people that backwards time travel is impossible:

The dead giveaway that true time-travel is flatly impossible arises from the well-known “paradoxes” it entails. The classic example is “What if you go back into the past and kill your grandfather when he was still a little boy?”…So complex and hopeless are the paradoxes…that the easiest way out of the irrational chaos that results is to suppose that true time-travel is, and forever will be, impossible. (Asimov 1995 [2003, 276–7]) travel into one’s past…would seem to give rise to all sorts of logical problems, if you were able to change history. For example, what would happen if you killed your parents before you were born. It might be that one could avoid such paradoxes by some modification of the concept of free will. But this will not be necessary if what I call the chronology protection conjecture is correct: The laws of physics prevent closed timelike curves from appearing . (Hawking, 1992, 604) [ 14 ]

The paradox comes in different forms. Here’s one version:

If time travel was logically possible then the time traveller could return to the past and in a suicidal rage destroy his time machine before it was completed and murder his younger self. But if this was so a necessary condition for the time trip to have occurred at all is removed, and we should then conclude that the time trip did not occur. Hence if the time trip did occur, then it did not occur. Hence it did not occur, and it is necessary that it did not occur. To reply, as it is standardly done, that our time traveller cannot change the past in this way, is a petitio principii . Why is it that the time traveller is constrained in this way? What mysterious force stills his sudden suicidal rage? (Smith, 1985, 58)

The idea is that backwards time travel is impossible because if it occurred, time travellers would attempt to do things such as kill their younger selves (or their grandfathers etc.). We know that doing these things—indeed, changing the past in any way—is impossible. But were there time travel, there would then be nothing left to stop these things happening. If we let things get to the stage where the time traveller is facing Grandfather with a loaded weapon, then there is nothing left to prevent the impossible from occurring. So we must draw the line earlier: it must be impossible for someone to get into this situation at all; that is, backwards time travel must be impossible.

In order to defend the possibility of time travel in the face of this argument we need to show that time travel is not a sure route to doing the impossible. So, given that a time traveller has gone to the past and is facing Grandfather, what could stop her killing Grandfather? Some science fiction authors resort to the idea of chaperones or time guardians who prevent time travellers from changing the past—or to mysterious forces of logic. But it is hard to take these ideas seriously—and more importantly, it is hard to make them work in detail when we remember that changing the past is impossible. (The chaperone is acting to ensure that the past remains as it was—but the only reason it ever was that way is because of his very actions.) [ 15 ] Fortunately there is a better response—also to be found in the science fiction literature, and brought to the attention of philosophers by Lewis (1976). What would stop the time traveller doing the impossible? She would fail “for some commonplace reason”, as Lewis (1976, 150) puts it. Her gun might jam, a noise might distract her, she might slip on a banana peel, etc. Nothing more than such ordinary occurrences is required to stop the time traveller killing Grandfather. Hence backwards time travel does not entail the occurrence of impossible events—and so the above objection is defused.

A problem remains. Suppose Tim, a time-traveller, is facing his grandfather with a loaded gun. Can Tim kill Grandfather? On the one hand, yes he can. He is an excellent shot; there is no chaperone to stop him; the laws of logic will not magically stay his hand; he hates Grandfather and will not hesitate to pull the trigger; etc. On the other hand, no he can’t. To kill Grandfather would be to change the past, and no-one can do that (not to mention the fact that if Grandfather died, then Tim would not have been born). So we have a contradiction: Tim can kill Grandfather and Tim cannot kill Grandfather. Time travel thus leads to a contradiction: so it is impossible.