Understanding Intrastate Travel Restriction And Its Implications: What You Need To Know

- Last updated Sep 16, 2023

- Difficulty Intemediate

- Category United States

In the face of a global pandemic, governments around the world have been implementing various measures to curb the spread of the virus. One such measure has been the introduction of intrastate travel restrictions, which aim to limit non-essential travel within a country's borders. These restrictions have had a significant impact on individuals' ability to move freely within their own country and have sparked debates about personal freedoms and the effectiveness of such measures. In this article, we will explore the reasons behind intrastate travel restrictions, their implications on individuals and communities, and the ongoing debates surrounding their implementation.

What You'll Learn

What are some common reasons for intrastate travel restrictions to be implemented, how do intrastate travel restrictions impact the tourism industry, what are the potential economic consequences of intrastate travel restrictions, how do intrastate travel restrictions affect individuals who commute across state lines for work, what criteria are typically used to determine when to implement or lift intrastate travel restrictions.

Intrastate travel restrictions, or restrictions on travel within a specific state or province, can be implemented for various reasons. These restrictions are typically put in place by local or state governments in order to protect public health and safety, and to control the spread of infectious diseases. Here are some common reasons why intrastate travel restrictions may be implemented:

- Public Health Emergencies: One of the main reasons for intrastate travel restrictions is to respond to public health emergencies, such as a pandemic or an outbreak of a contagious disease. In these situations, travel restrictions may be imposed to limit the movement of people and prevent the spread of the disease.

- Quarantine Requirements: Travel restrictions may also be implemented to enforce quarantine requirements. If an individual has been exposed to a contagious disease or has tested positive for a disease, they may be required to quarantine for a certain period of time. Travel restrictions can help enforce these quarantine measures and prevent infected individuals from spreading the disease to others.

- Natural Disasters: Intrastate travel restrictions can also be imposed in response to natural disasters, such as hurricanes, floods, or wildfires. These restrictions may be put in place to ensure the safety of residents and to control the movement of people in areas that have been affected by the disaster.

- Civil Unrest or Security Threats: In some cases, travel restrictions may be implemented in response to civil unrest or security threats. These restrictions are typically put in place to maintain public order and protect the safety of residents. For example, during periods of civil unrest, the government may impose curfews or restrict travel to certain areas to prevent violence or further unrest.

- State of Emergency: Travel restrictions may also be implemented during a state of emergency, which is declared by the government in response to a significant threat to public health, safety, or welfare. During a state of emergency, the government may have broader powers to restrict travel and enforce other measures to protect the public.

It is important to note that the specific travel restrictions and their duration can vary depending on the situation and the state or province implementing them. Travelers should always check with local authorities or official sources for the most up-to-date information on any travel restrictions before planning their trips.

Canada Eases Travel Restrictions: What It Means for Travelers

You may want to see also

Intrastate travel restrictions have had a profound impact on the tourism industry. As governments implemented measures to curb the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, they imposed restrictions on travel within their jurisdictions. While these restrictions were necessary from a public health standpoint, they had far-reaching consequences for the tourism sector.

One of the most immediate effects of intrastate travel restrictions was a significant decline in tourism activities. With people unable to travel freely within their own states or provinces, many tourist destinations saw a sharp decrease in visitor numbers. This led to closures of hotels, restaurants, and other businesses that relied on tourist income. As a result, thousands of jobs were lost, and local economies suffered.

Moreover, the tourism industry is an intricate web of interconnected businesses. For example, hotels rely on various service providers, such as laundry services and food suppliers, to operate smoothly. With intrastate travel restrictions in place, the demand for these services decreased, leading to a ripple effect that impacted multiple sectors. Small businesses that catered to tourists, such as souvenir shops and local tour operators, were particularly hard hit, as they often lack the financial resources to weather prolonged closures.

Furthermore, intrastate travel restrictions had a profound impact on larger tourist destinations that rely heavily on domestic tourism. When people are unable to travel freely within their own countries, they are more likely to seek alternative options closer to home or simply opt to stay put. This led to a redistribution of tourist spending and a concentrated impact on popular tourist hotspots. In turn, this had a devastating effect on local economies that heavily depended on tourism revenue.

Another consequence of intrastate travel restrictions on the tourism industry was the disruption of international travel. Many countries welcomed foreign tourists, but with domestic travel restricted, the necessary infrastructure and services were not in place to accommodate them. This severely impacted international tourism numbers, as people were unable to travel within a country to visit renowned attractions or access transportation hubs. The loss of international tourists further exacerbated the economic impact, as they often spend more money and stay for longer periods than domestic tourists.

Unfortunately, the tourism industry was one of the hardest-hit sectors during the pandemic, and the impact of intrastate travel restrictions cannot be understated. While these restrictions were necessary to protect public health, they highlighted the sector's vulnerability and the urgent need for governments to support and invest in tourism recovery efforts. As travel restrictions are gradually lifted, the tourism industry will need targeted support and innovative strategies to rebuild and thrive in a changed world.

Exploring Cancun: Are There Any Current Travel Restrictions?

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many countries and states have implemented restrictions on intrastate travel. These restrictions have been aimed at limiting the spread of the virus and protecting public health. While they may be necessary from a public health standpoint, they can have significant economic consequences.

One potential economic consequence of intrastate travel restrictions is a decline in tourism. Many states rely heavily on tourism as a major source of revenue, and restrictions on travel can severely impact this sector. Hotels, restaurants, and other tourist attractions may suffer from a lack of visitors, leading to decreased revenue and potentially even closures. In addition, businesses that support the tourism industry, such as transportation providers and tour operators, may also be negatively affected.

Another consequence of intrastate travel restrictions is a decrease in consumer spending. When people are unable to travel and explore different areas within their state, they may be more inclined to stay home and save their money. This can have a ripple effect on the economy, as businesses in sectors such as retail, hospitality, and entertainment may experience a decline in sales.

Furthermore, intrastate travel restrictions can have a detrimental impact on small businesses. Small businesses often rely on local customers and foot traffic to survive. When travel is restricted, the customer base for these businesses is limited, making it difficult for them to generate revenue. This can result in layoffs, business closures, and a negative impact on local economies.

Additionally, the implementation of intrastate travel restrictions can lead to job losses. The tourism, hospitality, and transportation sectors are major employers in many states. When travel is restricted, these industries may be forced to lay off workers or reduce their hours, which can have a significant impact on individuals and families. Moreover, other industries that rely on tourism and travel, such as the manufacturing and agriculture sectors, may also experience job losses.

Intrastate travel restrictions can also hinder economic growth and development. When people are confined to their local areas, it can be difficult for businesses to expand and reach new markets. This can limit opportunities for economic growth and innovation, potentially slowing down the overall development of a state's economy.

In conclusion, while intrastate travel restrictions may be necessary to protect public health, they can have significant economic consequences. The decline in tourism, decrease in consumer spending, negative impact on small businesses, job losses, and hindered economic growth are all potential consequences of these restrictions. As governments continue to navigate the balance between public health and economic recovery, it is important to consider the potential economic consequences of intrastate travel restrictions and implement measures to mitigate these impacts.

Hong Kong and Macau Travel Restrictions: What You Need to Know

Intrastate travel restrictions have become a common measure implemented by governments to control the spread of infectious diseases such as COVID-19. These restrictions can have a significant impact on individuals who commute across state lines for work, creating numerous challenges and difficulties in their daily lives.

One of the major issues faced by individuals commuting across state lines is the disruption of their regular work routine. With intrastate travel restrictions in place, it becomes difficult to maintain a consistent schedule and to be present at work as required. This can lead to reduced productivity and potential setbacks for both employees and employers.

Moreover, intrastate travel restrictions may also disrupt the availability of essential services, such as healthcare and emergency services, for individuals living in border areas. In emergency situations, quick access to healthcare facilities or the ability to respond to emergencies promptly can be compromised due to these restrictions.

Another challenge faced by commuters is the added financial burden. Traveling across state lines often involves additional costs such as toll fees, transportation expenses, and potentially higher fuel costs. With travel restrictions in place, individuals may have to find alternative routes or modes of transportation, which can be more time-consuming and costly.

Furthermore, intrastate travel restrictions can lead to psychological stress and reduced well-being among commuters. The uncertainty of being able to travel freely across state lines can cause anxiety and frustration. Additionally, the fear of being unable to reach their workplace in time or the possibility of losing their job due to travel restrictions can adversely affect mental health.

Burnout and fatigue can also result from long and stressful commutes caused by intrastate travel restrictions. When individuals have to travel longer distances or take detours to avoid restricted areas, it can lead to increased travel times and ultimately affect their work-life balance.

To mitigate the impact of intrastate travel restrictions on individuals who commute across state lines for work, governments and employers can consider implementing certain measures. For instance, providing flexible work options such as remote work or adjusted schedules can help alleviate the difficulties faced by commuters. Employers can also explore the possibility of providing transportation assistance or incentives to ease the financial burden on employees.

Additionally, governments can work towards streamlining regulations and processes to facilitate smoother cross-state travel for essential workers. This can involve the creation of special permits or identification cards that allow individuals to commute freely, provided they meet certain criteria.

In conclusion, intrastate travel restrictions have a significant impact on individuals who commute across state lines for work. From disruptions to work routines and financial burdens to challenges in accessing essential services, commuting in such circumstances can be incredibly challenging. Implementing supportive measures and finding solutions to facilitate easier cross-state travel can help alleviate some of these difficulties and promote the well-being of these commuters.

Latest Africa Travel Restrictions from the US: What You Need to Know

Travel restrictions have become a common occurrence in the current global climate, with countries implementing measures to control the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. Intrastate travel restrictions refer to limitations on movement within a particular state or region within a country. These restrictions can vary in their severity and duration, depending on the situation at hand. However, determining when to implement or lift intrastate travel restrictions involves considering several key criteria.

- Epidemiological Factors: The first and most important criterion for implementing or lifting intrastate travel restrictions is the epidemiological situation in the region. This includes factors such as the number of active cases, the rate of transmission, and the availability of healthcare resources. If there is a high number of cases and a rapid increase in transmission, restrictions may be implemented to prevent further spread. On the other hand, if the situation improves and cases decrease, restrictions can be lifted.

- Public Health Recommendations: Travel restrictions are typically based on public health recommendations from experts and authorities. These recommendations take into account the spread of the virus, the effectiveness of containment measures, and the potential risks associated with travel. The advice of public health officials and organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), can greatly influence the decision to implement or lift intrastate travel restrictions.

- Regional and Local Factors: In some cases, travel restrictions may be implemented or lifted based on regional or local factors. For example, if certain areas within a state or region have higher infection rates compared to others, restrictions may be tailored to those specific areas. Similarly, the lifting of restrictions can be done gradually, starting with low-risk areas and gradually expanding to higher-risk areas.

- Economic Implications: Travel restrictions can have significant economic implications, especially for industries such as tourism, hospitality, and transportation. Therefore, economic factors also play a role in the decision-making process. The impact on businesses, job losses, and the overall economic well-being of the region must be considered. However, it is important to strike a balance between economic concerns and public health considerations.

- Government Policies: The implementation or lifting of intrastate travel restrictions is ultimately determined by government policies. Governments have the authority to impose restrictions and make decisions in the best interest of public health and safety. These policies may vary depending on the political climate, the level of coordination between federal, state, and local authorities, and the overall strategy in managing the pandemic.

It is crucial to note that these criteria may vary between countries and even within different regions of a country. Each situation is unique, and decisions regarding travel restrictions are made based on the specific circumstances and available data. Communication, transparency, and ongoing monitoring of the situation are essential to effectively manage intrastate travel restrictions and ensure the health and well-being of the population.

Navigating the Latest CRA Travel Restrictions: What You Need to Know

Frequently asked questions.

An intrastate travel restriction refers to a restriction implemented by a government or authority within a specific state or province that limits or regulates travel within that area. It is typically put in place during times of emergency or crisis, such as a natural disaster or a public health outbreak, to prevent the spread of a disease or protect public safety.

Intrastate travel restrictions are implemented for a variety of reasons. In the case of a public health emergency, such as a pandemic, these restrictions are put in place to limit the movement of individuals to prevent the spread of the disease. This helps to contain the outbreak and protect vulnerable populations. During a natural disaster, travel restrictions may be implemented to ensure the safety of residents by preventing them from entering areas that have been impacted or are at high risk.

Enforcement of intrastate travel restrictions can vary depending on the specific circumstances and the level of government authority involved. In some cases, checkpoints may be set up along major highways or at state borders to monitor and restrict the movement of individuals. Law enforcement agencies may also be involved in enforcing these restrictions, issuing fines or penalties for non-compliance. Additionally, travel permits or documentation may be required to prove essential travel purposes, such as for work or medical reasons, and individuals may be subject to questioning or screening when traveling within the restricted area.

- Kamilla Henke Author

- Naim Haliti Author Editor Reviewer Traveller

It is awesome. Thank you for your feedback!

We are sorry. Plesae let us know what went wrong?

We will update our content. Thank you for your feedback!

Leave a comment

United states photos, related posts.

13 Great Things to Do in Nelsonville, Ohio

- May 07, 2023

Understanding the Nauru Travel Restrictions: What You Need to Know

- Sep 27, 2023

The Ultimate Guide to Packing Your Fanny Pack for Raves

- Dec 03, 2023

Fun and Safe Nighttime Activities for Under 21s in Tampa: Exploring the City's Vibrant Nightlife

- Jul 08, 2023

Travel Restrictions: From Guatemala to the US, What You Need to Know

- Nov 07, 2023

Essential Items to Bring for a Transformative Meditation Retreat Experience

- Dec 23, 2023

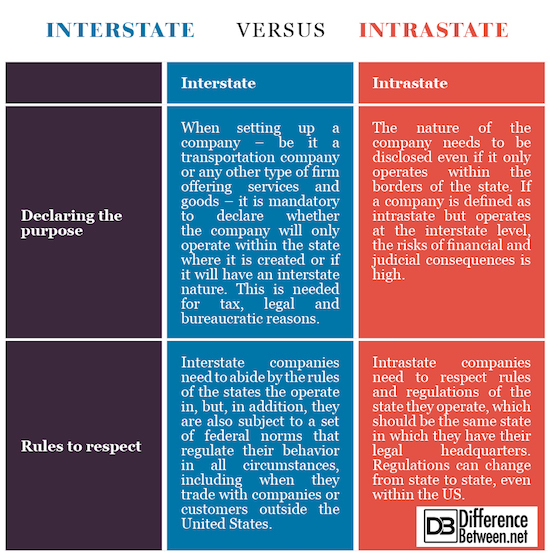

Interstate vs. Intrastate

What's the difference.

Interstate and intrastate are two terms commonly used in transportation and commerce. Interstate refers to activities or transactions that occur between two or more states within a country. It involves the movement of goods, services, or people across state borders, often regulated by federal laws and regulations. On the other hand, intrastate refers to activities or transactions that occur within a single state. It involves the movement of goods, services, or people within the boundaries of a particular state, often regulated by state laws and regulations. While both interstate and intrastate activities contribute to the overall economic development of a country or state, they differ in terms of the jurisdiction and regulations that govern them.

Further Detail

Introduction.

When it comes to transportation and logistics, understanding the differences between interstate and intrastate operations is crucial. Both terms refer to the movement of goods or passengers, but they have distinct characteristics and regulations. In this article, we will explore the attributes of interstate and intrastate operations, highlighting their similarities and differences.

Interstate Operations

Interstate operations involve the transportation of goods or passengers between two or more states. These operations are subject to federal regulations and oversight, primarily governed by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) in the United States. One of the key attributes of interstate operations is the need for carriers to obtain an operating authority from the FMCSA, which includes a Motor Carrier (MC) number. This number is essential for carriers to engage in interstate commerce legally.

Interstate carriers must also comply with various safety regulations, such as maintaining proper insurance coverage, adhering to hours-of-service rules, and conducting regular vehicle inspections. These regulations aim to ensure the safety of both the carriers and the general public. Additionally, interstate carriers are required to display the USDOT (United States Department of Transportation) number on their vehicles, allowing for easy identification and monitoring.

Another important attribute of interstate operations is the requirement for carriers to file quarterly International Fuel Tax Agreement (IFTA) reports. These reports help determine the appropriate fuel taxes owed to each state based on the miles traveled within their jurisdictions. Interstate carriers must carefully track their mileage and fuel purchases to accurately complete these reports and fulfill their tax obligations.

Furthermore, interstate operations often involve long-haul transportation, covering vast distances and crossing state lines. This requires carriers to have a deep understanding of the different state regulations they encounter along their routes. They must be knowledgeable about varying weight limits, permit requirements, and any specific restrictions imposed by individual states.

In summary, interstate operations involve transportation between states, necessitating compliance with federal regulations, obtaining operating authority, adhering to safety standards, filing IFTA reports, and navigating diverse state regulations.

Intrastate Operations

Intrastate operations, as the name suggests, refer to transportation activities that occur solely within the boundaries of a single state. Unlike interstate operations, intrastate operations are subject to state regulations rather than federal oversight. Each state has its own transportation department or agency responsible for regulating intrastate carriers.

One of the primary attributes of intrastate operations is the absence of the need for an MC number or federal operating authority. Carriers engaged in intrastate commerce are typically required to obtain a state-specific operating authority or permit, which may involve meeting certain insurance requirements and paying applicable fees.

While intrastate carriers are not subject to federal safety regulations like their interstate counterparts, they are still required to comply with state-specific safety standards. These standards often mirror federal regulations, ensuring a consistent level of safety across both interstate and intrastate operations.

Unlike interstate carriers, intrastate carriers do not need to file IFTA reports since their operations are confined within a single state. However, they may still be subject to state-specific fuel tax reporting and payment requirements. These requirements vary from state to state, and carriers must stay informed about the specific regulations in each jurisdiction they operate within.

Another attribute of intrastate operations is the potential for shorter hauls and more localized transportation. Carriers primarily serve customers within their own state, which can lead to more efficient operations and reduced transit times. Additionally, intrastate carriers may have a better understanding of the local infrastructure, traffic patterns, and specific customer needs within their state.

In summary, intrastate operations involve transportation within a single state, subject to state regulations, obtaining state-specific operating authority, complying with state safety standards, potential exemption from IFTA reporting, and focusing on localized transportation needs.

Interstate and intrastate operations have distinct attributes that differentiate them in terms of regulations, operating authority requirements, safety standards, and reporting obligations. While interstate operations involve transportation between states and are subject to federal oversight, intrastate operations occur solely within a single state and are regulated by state-specific agencies. Understanding these differences is essential for carriers, shippers, and logistics professionals to ensure compliance and efficient transportation operations.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Tourism economics and policy analysis: Contributions and legacy of the Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre

Larry dwyer.

a Faculty of Economics, University of Ljubljana, Griffith Institute for Tourism (GIFT), Griffith University, School of Marketing, University of New South Wales, Australia

Peter Forsyth

b Monash University and Southern Cross University, Australia

Raymond Spurr

c Centre for Economic Policy, Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre, Australia

The Centre for Economic Policy (CEP) located within Australia's Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre, engaged with government, industry and researchers for over a decade to advance policy analysis in tourism contexts. This paper discusses the contributions of the CEP in three major areas-the development of tourism satellite accounts, economic impact analysis and policy evaluation. The conceptual and empirical work undertaken by CEP, and the fertile research agenda it developed, is incomplete and poses an ongoing challenge to tourism researchers, practitioners and destination managers internationally to help to progress the advances already made.

1. Introduction

The Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre (STCRC) was first established under the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centres (CRC) Program at the end of 1997, and re-funded for a further seven-year term commencing July 2003. The CRC Program was an initiative of the Australian Government designed to drive innovation by providing funding to support collaborative links between industry, research organisations, educational institutions, and relevant government agencies. It aimed to bring the highest quality research providers and industry together, to focus on outcomes for business, community, and the environment.

The STCRC brought together academic and industry participants as members. Its mission was to lead the world in sustainable tourism research, commercialisation, extension and education. Specific goals were to provide intellectual leadership for the sustainable development of Australian tourism, engaging with government and industry to produce knowledge products to position Australia as the centre of tourism innovation and world's best practice. As part of its research program the STCRC established a Centre for Economic Policy (CEP) that produced research in tourism economics and policy analysis which was to be at the ‘cutting edge’ internationally.

This paper provides an overview of some of the important contributions made by CEP during the life of the STCRC. It is not intended as an historical account of the theoretical and practical contributions made to tourism economics by the CEP. Rather, it aims to emphasise their continued relevance in an unfinished research agenda. The fertile research agenda developed by CEP is incomplete and poses an ongoing challenge to tourism researchers, practitioners and destination managers internationally to help to progress the work already undertaken.

The contributions of the CEP were wide ranging but can be classified under three main headings-tourism satellite accounting, computable general equilibrium modelling, and policy analysis.

2. Tourism satellite accounting

A major issue for the tourism industry, and for all levels of government dealing with it, was how to accurately assess the importance of tourism relative to other sectors of the economy, and from there to have a credible and rigorous means for assessing the impact of changes whether these came from developments in the industry itself or the wider economy, or as a result of the policies or actions of governments.

The most credible data source for data on tourism demand and the supply of tourism industries is a national or regional Tourism Satellite Account (TSA). TSAs are constructed using a combination of visitor expenditure data, industry data, and Supply and Use Tables from the system of national accounts of destinations. TSAs provide detailed production accounts for the tourism industries, including data on employment, and linkages with other productive economic activities. They provide an internationally recognized and standardized method of assessing the scale and impact of tourism related production and its links across different sectors ( Spurr, 2006 ).

While TSA were initially developed with support of the UNWTO as primarily a national level concept constructed within a country's system of national accounts, many of the key decisions in planning and development and management of tourism occur at the local and regional level and are the responsibility of regional/state or local governments, regional destination management organisations and local businesses. In 2001 the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) published its first experimental TSA for Australia. CEP participated in consultations with the ABS on the development and implementation of the national TSA and then worked with the national and state governments to develop a methodology to extend the TSA structure down to the sub-national level. CEP subsequently began to produce annually updated regional tourism accounts for each of the eight Australian states and territories. For the first time internationally, regional tourism accounts were produced across a whole country which were fully consistent both between the states and with the national TSA ( Ho et al., 2008 , Pambudi et al., 2009 , Spurr et al., 2007 ). These reports were continued over the remaining seven years of the STCRC's life and have subsequently been produced by the government research agency Tourism Research Australia (TRA).

In a further development, extending national TSA estimates downwards to regions below the state level, CEP subsequently published a set of regional tourism economic accounts for nine tourism regions in the Australian state of Queensland accompanied by a detailed discussion of the methodology used in producing these estimates ( Dwyer et al., 2008b , Pham et al., 2009 , Pham et al., 2010a ).

Regional TSA have since become a significant program for research and development under the International Network on Regional Economics, Mobility and Tourism (INRouTe), a collaborative study initiated through the UNWTO and Centre for Cooperative Research in Tourism, Spain (CICtourGUNE) which is seeking to develop a set of general guidelines on measurement and economic analysis of tourism at sub-National levels prior to a proposed worldwide consultation in 2016. The work of the CEP in respect of developing consistent concepts, definitions and methodologies to ensure credibility and comparability between the national TSA standards and Tourism Accounts developed at the state and regional levels foresaw much of this work and was described in several journal publications ( Pham et al., 2008 , Pham et al., 2009 ).

A further important extension of the TSA methodology undertaken by the CEP was the estimation of the wider flow on effects which tourism generates across the economy generally (indirect effects). The TSA, based as it is on the direct contribution of tourism, measures only the effects of direct transactions between the visitor and a domestic supplier of a tourism good or service. The Australian government's tourism research agency, Tourism Research Australia, had extended this by producing estimates of the total, direct plus indirect, contribution of tourism to the economy. The CEP further extended these estimates to the state and territory level in a report on the indirect contribution of tourism ( Ho et al., 2007 ). These estimates were subsequently incorporated into the CEP's annual state and territory TSA.

Research by the CEP had always been driven by a conviction that there is substantial scope for using the TSA methodology to provide a structure for more detailed breakdowns of the information they provide. Using the TSA methodology, CEP developed detailed estimates of taxation from tourism by type of tax and level of government in receipt of the revenue ( Forsyth et al., 2007 ).

Along the way, members of CEP participated internationally in intergovernmental Advisory Groups, Workshops and Conferences held by the UNWTO and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in the development of the agreed TSA methodology and the dissemination of information and training on the TSA. They contributed to the development of private sector inputs to the TSA negotiations by the WTTC (World Travel and Tourism Council). And they assisted the UNWTO in developing a methodology for measuring the size of the business tourism sector ( Dwyer, Deery, Jago, Spurr, & Fredline, 2007 ).

CEP research ( Dwyer et al., 2007b , Dwyer et al., 2007d ) also performed a useful contribution to the literature by clearly distinguishing between the economic contribution (a TSA measure) and its economic impacts (estimated through economic modelling), a distinction often confused by researchers. CEP was among the first to recognise that TSA provide the basic information required for the development of models of the economic impact of tourism. A TSA is a necessary tool to adapt I-O tables and national accounts (and thus Social Account Matrixes derived from them) to tourism specificities. CGE models developed by CEP for tourism industry analysis included tourism data from Australia's national TSA giving the work a credible and consistent data base for modelling tourism's economic impacts ( Dwyer et al., 2003 , Dwyer et al., 2005b , Pham and Dwyer, 2013 ). CEP analysis demonstrated that a CGE model, which is constructed with an explicit tourism sector in a manner consistent with the national TSA, and which draws on national TSA definitions and data, can provide an appropriate and cost effective tool for producing simulated TSA's at the state/provincial level ( Dwyer et al., 2005 ). If the assumptions and definitions adopted to build the tourism specific components of the CGE model are consistent with those of an official TSA structure the resulting CGE generated TSA should be broadly consistent with what would be produced in a fully constructed TSA.

Several measures of tourism yield have been developed by CEP using the data contained in TSA. These include expenditure per tourist, return on capital, profitability, GDP, value added, and employment. Given that TSA distinguish the numbers and expenditure of different tourist markets by origin the yield contribution measures can be developed per tourist by origin market ( Dwyer et al., 2006a , Dwyer et al., 2007c ). CEP research further identified the manner in which the concept of yield can be broadened to embrace sustainable yield by incorporating measures of environmental and social impact ( Dwyer and Forsyth, 2008 , Lundie et al., 2007 ). Adding environmental and social dimensions to the yield concept implies, however, that decision makers have to deal increasingly with trade-offs between economic and environmental and social dimensions, respectively.

A relatively neglected research topic has been measures of tourism productivity at the industry level. TSA can be used to develop performance indicators such as measures of productivity, prices and profitability for the tourism industry as a whole. They can also be used to explore performance in individual sectors. Tourism researchers now have the data to explore the performance of individual tourism sectors or of the entire tourism industry relative to that of other industries, domestically and internationally.

TSA provide the opportunity for tourism economists to contribute to our understanding of the ‘carbon footprint’ associated with the tourism industry. The advantage of using the TSA to estimate the carbon footprint is that it ensures that the measure is comprehensive, and incorporates all emissions from all industries which make up tourism. That is, if the relationship between industry production and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is known, then it is possible to calculate the emissions which are due to tourism, by applying these relationships to the TSA industry output data. Since the TSA is extensively used as a measure of the size of the economic contribution of the tourism industry, this carbon footprint is an environmental measure which is consistent, in terms of definition of the industry, with the economic measures. The CEP explored the issues in estimating the GHG emissions from the tourism industry and related activity in Australia ( Dwyer et al., 2010b , Dwyer et al., 2011 ). Two approaches were employed and contrasted-a ‘Production Approach’ and an ‘Expenditure Approach’. These studies showed that, depending on the approach adopted, tourism contributes between 3.9 per cent and 5.3 per cent of total industry greenhouse gases in Australia. Depending on the precise inclusions and exclusions, tourism was found to rank between 5th and 7th of all Australian industries in respect of its volume of carbon emissions ( Forsyth et al., 2008 ). CEP also extended this analysis to estimate tourism's carbon footprint at the regional level for the Australian state of the Queensland using a methodology which could be readily replicated to make similar estimates for other Australian states and territories, and potentially for regions in other countries through the use of regional TSA data ( Hoque et al., 2010 ). Estimating tourism's carbon footprint represents a starting point for the development of industry strategies to mitigate and adapt to climate change. The approach adopted by CEP is applicable to any destination with a TSA, enabling tourism stakeholders to play an informed role in assessing appropriate climate change mitigation strategies for their destination.

3. Contributions to economic impact analysis and policy

The study of the economic impacts of shocks to tourism demand (positive or negative) has recently undergone a ‘paradigm shift’ as a result of the use of computable general equilibrium (CGE) models in place of Input-Output (I-O) models. CEP from its inception recognised the need for a change of approach to estimating the economic impacts of tourism ( Dwyer et al., 2000 , Dwyer et al., 2004 ). The CEP contribution was two-fold. One contribution involved a series of papers that criticised the ‘Standard View’ of estimating the economic impacts of a shock to tourism demand. Another type of contribution involved a series of papers of an empirical nature that demonstrated the power of the alternative CGE approach to impact analysis with far greater tourism policy relevance.

3.1. Criticism of the ‘Standard Approach’

Increased tourism expenditure from inbound markets potentially has direct, indirect and induced effects on a host destination, leading to increased production, income and employment. To estimate the multiplier effects of the increased expenditure the standard approach of researchers and consultants was to employ an I-O model. In several papers, CEP researchers argued that this standard approach to economic evaluation in the tourism context, fails to satisfy best practice assessment. The criticisms of I-O modelling focussed on the rigidity of its assumptions and its unsuitability for policy analysis ( Dwyer et al., 2000 , Dwyer et al., 2004 , Dwyer et al., 2008a ).

Unless there is significant excess capacity in tourism-related industries, the primary effect of a tourism demand shock in economy-wide expansion in inbound tourism is to alter the industrial structure of the economy rather than to generate a substantial increase in aggregate economic activity, including income and employment generation. Its effect will thus show up as a change in the composition of the economy rather than as a net addition to activity. An outcome of the CEP research, together with contributions by other critics of I-O modelling (e.g. the Nottingham group associated with Thea Sinclair and Adam Blake), was a greater awareness among tourism researchers that, for any given expenditure shock to a destination, the change in economic variables will vary according to features of the economy such as: the particular industries that are the recipients of the direct expenditure; strengths of the business linkages between the different industry sectors in the economy; the assumed factor constraints (supplies of land, labour, capital); the import content of consumer goods and inputs to production; the production and consumption relationships assumed; changes in the prices of inputs and outputs; changes in the exchange rate; the workings of the labour market; and the government fiscal policy stance. This increased awareness has made economic impact analysis more complex while enhancing its policy relevance ( Dwyer & Pham, 2012 ). While I-O modelling is incapable of taking account of these features of real world economies, it came to be recognised that an alternative approach, based on CGE modelling could do so.

3.2. Development of a CGE model

CEP policy analysis from its inception was based on the conviction that, in evaluating economic impacts of tourism, there is a need to model the economy, as far as is possible, as it really is, recognising other sectors and markets and capturing feedback effects. This required the development of a CGE model comprising a set of behavioural and structural equations that characterize the production, consumption, trade and government activities of the Australian economy. The model constructed was known as ‘M2RNSW’, a modified version of the M2R model ( Han, Madden, & Pant, 1998 ), the basis of which is an adaptation of the Monash multi-regional forecasting (MMRF) model of Australia's states and territories ( Naqvi & Peter, 1996 ). A two-region model was created by preserving the separate identity of only the state of New South Wales, while the other seven regions of MMRF were aggregated into a single ‘Rest of Australia’ region. A key feature of the CRC model, absent from most other CGE models at the time, was its explicit incorporation of tourism sectors including international visitors, interstate and intrastate visitors, and international outbound tourism. Allowance was also made for different tourist types (business, holiday, visiting friends, other). The model's tourism database was made consistent with national and state TSA data. Details of the model are given in Dwyer et al., 2003 , Dwyer et al., 2005b .

CEP came to play a world leadership role in respect to the use of CGE models for estimating the economic impacts of tourism shocks. CGE models are helpful to tourism policy makers who seek to use them to provide guidance about a wide variety of ‘what if?’ questions, arising from a wide range of domestic or international expenditure shocks or alternative policy scenarios. The M2RNSW model provided a substantial capacity for the CEP to measure the impact of tourism on the Australian economy, and the effects of changes in tourism flows or conditions, nationally and regionally, but the influence of CEP approaches and findings travelled well beyond Australia's borders. The discussion below addresses the contributions made to economic impact analysis and policy.

3.2.1. Economic impacts of inbound tourism

In an early application of the CGE model, CEP estimated the effects of an increase in world, interstate and intrastate tourism on the economy of Australia's largest state, New South Wales ( Dwyer et al., 2003 ). Compared to the international tourism market, domestic tourism has tended to be neglected by both tourism stakeholders and researchers. An assumption has prevailed among tourism stakeholders and researchers that, nationally and within a state's borders, domestic tourism represents mainly transfers of expenditure, with minimal impacts on GSP and employment. The CEP simulations showed that this neglect is unfortunate. Depending on what is given up by intrastate tourists to finance their trip, intrastate tourism may have greater impacts per dollar expended than the more emphasized ‘glamour’ markets of inbound (international and interstate) tourism. Another significant finding was that increases in interstate tourism are associated with relatively large economic impacts on the state regardless of whether the substitution relates to other tourism or to (non-tourism) goods and services. There are important implications here also for the treatment of resident expenditure as ‘transferred expenditure’ in assessing the economic impacts of special events (see below). The study also indicated that promotional spending in domestic tourism markets might have greater cost effectiveness than international marketing expenditure, a result with important implications for DMOs. Also relevant to DMO (STO) strategy is the support this study gave to the earlier findings of Adams and Parmenter (1995) that some states which simply maintain their market share of a growing market may experience a fall in their GSP and overall employment, depending on the composition of their industry. Once this result is more fully appreciated by state tourism authorities it is likely to produce additional pressures on cooperative destination marketing arrangements ( Dwyer, 2003 ).

3.2.2. Tourism crises

Studies of crises using CGE models reveal that crises affecting tourism affect other industries as well and the total impact must be considered in formulating policy responses. CGE modelling provides valuable input into policy formulation with its identification of gainers and losers from exercising different crisis responses.

Australian tourism experienced the effects of two major crises in 2003—the Iraq War and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). While conceding that the relative impacts of a complex array of impacts on travel decision-making are almost impossible to dissect, CEP explored the economic effects of these crises on tourism to Australia. Although the SARS crisis resulted in less inbound tourism, it also led to reduced outbound tourism from Australia. The net economic impacts on the nation depend upon the extent to which cancelled or postponed outbound travel are allocated to savings, to domestic tourism, or to the purchases of other goods and services. Once substitution effects are accounted for, the net impact of the crisis was seen to be substantially less than had been thought. CEP CGE simulations, recognising that increased domestic tourism to some extent counteracts the fall in inbound tourism, showed that the net effects for the tourism industry as a whole and for the overall economy were not as severe as were feared by tourism stakeholders ( Dwyer et al., 2006c , Dwyer et al., 2006e ).

The CEP modelling exercise revealed several issues regarding the economic effects of tourism crises that need further research. One concerns the estimation of the ‘pent-up’ demand for travel following a period of travel postponements and cancellations. In general, the focus of attention has been on the economic losses in the crisis period rather than on subsequent periods. Information on the latter is of obvious use for strategic planning by stakeholders in both the public and private sectors. Additionally, the question of what types of expenditures are made by residents in lieu of outbound travel is an important but under-researched topic in the crisis literature. Another neglected area of research concerns those residents who substitute an international holiday for a domestic experience. Such travellers may have a greater tendency to fly to their destination, raising questions about the influence of crises on the type of tourism undertaken and the extent to which both the volume and patterns of domestic tourism expenditure change. These issues remain under-researched in the tourism literature.

3.2.3. Special events

CEP researchers have made a substantial contribution to the economic evaluation of special events both in development of frameworks for event assessment ( Dwyer and Jago, 2012 , Jago and Dwyer, 2006 ), as well as in identifying the main elements of a CGE approach to event evaluation ( Dwyer et al., 2005a , Dwyer et al., 2006b , Dwyer et al., 2006c ). CEP researchers also published several papers emphasising the importance of benefit measures to inform policy making in the events area (to be discussed in Section 4 ).

A particular target of CEP criticism of event assessment was the standard use of I-O modelling to derive multipliers that were then used to estimate the impacts of events on economic variables such as GDP/GRP, household income and employment. In real world economies which are subject to resource constraints, the net impact on output and jobs from a boom in demand associated with a special event is much less than I-O modelling suggests. Continued use of I-O modelling by researchers and consultants, where impact estimates across all industries were uniformly positive, raised the strong presumption among CEP researchers that overall, there was excessive funding being devoted to subsidising events, and that the funds being used are probably being misallocated ( Dwyer et al., 2004 ).

A study by Dwyer et al., 2005a , Dwyer et al., 2006c , Dwyer et al., 2006d ) compared the results of using CGE and I–O modelling to estimate the economic impacts of a special event held in the State of New South Wales (NSW). The expenditure data were based on that for the Qantas Australian Grand Prix of 2000 (but with the location transposed from Melbourne to Sydney). The I-O model yielded much larger multiplier values, and thus correspondingly larger projections of impacts on output, GSP, and employment than the CGE model, both for the host state of NSW and nationally. For the host state, the I-O multipliers for output, GSP and employment were, respectively, 80%, 100%, and 42% greater than the CGE counterparts. Contrasting the effects on the host state and the rest of Australia (RoA), the I–O model projected increased real output, GSP and employment in RoA as interstate firms supply industrial or consumer goods and services to meet the additional demand associated with the event in NSW. The CGE model, in contrast, projected decreased real output, GSP and employment in RoA. This is due to the fact that the expenditure by interstate visitors to the event must be financed by reduced expenditure within other states. The CGE model simulations also highlight those industries that contract as a result of the expenditure injection, something which I-O analysis is incapable of revealing. While I–O modelling projected a positive change in output and employment in all industries in the host state and nationally, the CGE model projected reduced output and employment in several industries in both jurisdictions. By ignoring the negative impacts of event related expenditure, the I-O study produced a grossly excessive estimate of the impact on economic activity.

CEP research clearly demonstrated that the type of model employed in event impact assessment is critically important to the findings. For larger events in particular, models need to reflect factor constraints, price changes (including the exchange rate), employment and wage realities and must recognise that some regions and industries will gain while others might lose. CEP research shows that new modelling approaches reflecting changing economic realities are more relevant than those traditionally employed, and are more likely to resonate with financial decision makers in government and industry. The research findings have influenced the direction of event assessment research globally.

3.2.4. Taxation

In an early paper, CEP researchers had argued that a serious emerging problem to tourism globally arises as individual countries each with market power over their tourism industry, impose taxes on tourism services and pass them on to foreign tourists. However, this constitutes a barrier to trade in tourism services, and what is rational for an individual country is inefficient for the world as a whole. Excessive taxation of international tourism will be the result, and this taxation will be very difficult to negotiate away. Ultimately, tourism growth is likely to suffer relative to other sectors in the global economy ( Forsyth & Dwyer, 2003 ). Given the ongoing imposition of tourism taxes globally, particularly on aviation, it would appear that this concern has not been heeded as different destinations, acting in their own self-interest, increase taxes on visitors.

3.2.5. The Passenger Movement Charge

The CEP CGE model was used to assess the impacts of Australia's form of a departure tax, the Passenger Movement Charge (PMC), on key economic variables, such as GDP, GNI and economic welfare, and on tourism industry output and employment ( Forsyth, Dwyer, Pham, & Spurr, 2014 ). The PMC is a tax on all persons departing Australia by air and sea. For Australia as a whole, a rise in the PMC is positive for Australia as a whole though it is negative for the tourism industry. The negative impact on the tourism industry is smaller to the extent that domestic tourism substitutes for outbound tourism. However, there will be a net positive impact on the economy as a whole because of the tax effect-a country gains from foreign tourists paying taxes rather than residents. This effect is sufficient to outweigh other impacts. This result contrasts with studies done in other countries of air passenger duties using I-O approaches. The study suggests that if funds become available, reducing the PMC would not be a cost effective way of helping the tourism industry, and that other methods, such as increasing promotion or measures directed to improving tourism industry productivity, may prove to be more cost effective for the economy as a whole.

3.2.6. Carbon tax

The development of ‘green’ CGE models is an important step towards identifying the extent of externalities associated with tourism and other industries. Based on the MMRF-GREEN model ( Adams, Horridge, & Wittwer, 2003 ) which was developed to estimate the greenhouse gas emissions associated with economic activity, CEP investigated the potential economic impacts of introduction by the Australian government of its now abandoned Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, a cap and trade mechanism for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Australia ( Dwyer et al., 2013 , Dwyer et al., 2012 ). While not targeted at tourism specifically, the carbon tax/ETS was proposed to create a price for carbon emissions, raising costs in those industries that directly or indirectly produce emissions, including tourism. CEP modelling showed that under the proposed scheme, the tourism sector would contract with falls in real tourism gross value added and tourism employment. The largest falls were projected to be in accommodation, air and water industries and in cafes, restaurants and food outlets. Overall, the gains experienced by some tourism industries will be heavily outweighed by contractions in some of the tourism characteristic industries. Since the direction of impacts on the tourism industry can be expected to be similar for any pricing scheme to reduce carbon emissions, the analysis is very relevant to engagement by the tourism industry in policy discussion on climate change mitigation measures and for enhancing our understanding of the implications for tourism of climate change mitigation policies generally.

Other studies relating to tourism and climate change were undertaken by CEP. The economic impacts of adaptation to climate change in five regions of Australia were estimated to 2070 as part of a wider STCRC study on a Climate Change adaptation ( Pham, Simmons, & Spurr, 2010 ). CEP researchers used a sub-state level CGE model of the Australian economy, known as TERM ( Horridge, 2012 ), and elaborated the model to incorporate the inbound and domestic tourism sectors explicitly for five tourism destinations in Australia. The model was then used to analyse the impacts of induced impacts of climate change via tourism on the destination economies. The analysis of tourism's carbon footprint, which was also extended down to regional level, made an important contribution to industry and government understanding of the implications of Climate Change policies in Australia. The type of analysis undertaken could be applied to destinations worldwide.

3.2.7. Dutch disease

Despite the reality that tourism industries around the world are facing the challenges of structural change posed by booming (non-tourism) sectors, discussion of Dutch Disease in the tourism literature has typically focussed on tourism as the booming sector leading to de-industrialisation. CGE modelling of the impacts of a mining boom on the Australian tourism industry by CEP confirms a Dutch Disease effect with tourism as the disadvantaged industry ( Dwyer et al., 2015b , Forsyth et al., 2014b , Pham et al., 2015 ).

From mid 2004 to 2012, Australian tourism faced a typical Dutch Disease situation, Mining as an export industry competed with other sectors of the economy for labour, capital and goods and services, thereby pushing up prices and the exchange rate. CEP used CGE modelling to assess impacts of the mining boom on the Australian economy and tourism in particular, through two broad mechanisms: an income effect and a price effect. The boost to household consumption provided by the boom through increased mining revenues supports increased demand for leisure tourism generally. These gains are offset, however, by reduced inbound tourism and increased outbound tourism resulting from the higher value of the Australian dollar. ‘Crowding out’ effects are most apparent for those parts of the tourism industry with greater dependence on leisure travel in the mining states, where competition from mining-related business travel is most intense, and in segments of the domestic industry which compete most directly with outbound travel.

The CGE analysis provided detailed macro and micro level estimates that indicate the complexities of the effects of the booming sector on tourism regionally (inter- and intra-state), by industry sector (accommodation and air services) and also for different tourism markets (e.g. leisure versus business travel). The micro level analysis, supplemented by input from key tourism organisations, highlights the extent and range of tourism impacts associated with the boom, and the implications for different groups of tourism stakeholders. Analysis of the regional and sectoral impact of the mining boom indicated that it represents a double-edged sword for Australian tourism stakeholders, with some components (e.g. business tourism) benefiting and other segments (e.g. leisure tourism) losing out. The modelling results showed that the boom delivered strong positive impacts to Australia's minerals rich states but adversely impacted upon the growth of the other states and territories. As the tourism sector does not supply many inputs to the mining sector, higher mining exports do not directly induce much demand for tourism. In contrast, the mining boom creates more competition for labour demand, particularly as wage rates in mining-related industries increase sharply. This means that traditionally lower-paying, less-skilled industries such as tourism have substantial difficulty competing with mining to attract and retain workers. The net economic effect on Australian tourism is negative, particularly in respect of the impacts of Fly-In-Fly-Out (FIFO) and Drive-In-Drive-Out (DIDO) workers in the mining states ( Pham, Bailey, Marshall, Spurr, & Dwyer, 2013 ).

The CEP research shows that structural changes taking place in a destination, underpinned by expanded exports in sectors other than tourism, can cause a substantial downturn in inbound and domestic tourism markets, with consequent gains and losses to different tourism stakeholders. A legacy of the mining boom is a leisure tourism sector under considerable pressure on a number of fronts. The CEP framework of analysis can be applied in destinations worldwide that are experiencing export booms in commodities other than tourism. Forsyth, Dwyer, and Spurr (2014) whether the same types of effects as those experienced in Australia exist in other destinations is an empirical matter, as is the size of these effects.

3.2.8. Yield and destination marketing

CGE modelling can be used to develop ‘economy-wide’ yield measures of tourist ‘worth’. Economy wide yield measures indicate the bottom line for the economy from tourist spending after all inter-industry effects have taken place ( Dwyer et al., 2006a , Dwyer et al., 2007c ). Dwyer and Forsyth (2008) estimated three economy wide yield measures associated with fourteen of Australia's major tourism origin countries and for three of Australia's regions. The yield measures are gross value added, gross operating surplus and employment. The economic impacts were then converted to yield measures by determining the economy wide effects of an additional tourist from each market. Yield measures based on CGE modelling can inform organizations in both the private and public sector about effective allocation of marketing resources and types of tourism development that meet operator and destination manager objectives. Further research is required as to how tourism economic yield can be usefully incorporated into a measure of sustainability incorporating economic, social and environmental dimensions.

The changing dynamics of the tourism marketplace, as well as increasing constraints on Destination Management Organisations (DMOs) to allocate scarce marketing funds efficiently, demand that the prospective return on investment in destination marketing be estimated as accurately as possible. From a public policy perspective, economy-wide measures of visitor yield provide information unavailable using other approaches. Using CGE modelling, CEP estimated the return on investment associated with promoting Australia in nine key visitor source markets ( Dwyer, Pham, Forsyth, & Spurr, 2014 ). While Australia provides a context for study, the approach taken by the CEP has relevance to destination marketing organizations worldwide.

CEP policy analysis revealed that the results of CGE modelling are sometimes surprising and indicate the value of using this sophisticated approach to impact analysis of tourism shocks in preference to standard I-O modelling. While it is likely that many of the results obtained by CEP for Australia are generalizable to other countries worldwide, the extent to which this is the case can only be determined by future studies that take account of the circumstances of different destinations.

4. Policy analysis

4.1. measuring the benefits and costs of tourism and airline liberalisation.

It is important to distinguish between impacts and (net) benefits of a tourism shock or policy initiative. Many studies estimate the impact of some change or policy on economic variables, such as the impact of carbon polices on tourism, the impact of a crisis such as SARS on GDP, through its effect on tourism, or the impact of an event on GSP and employment. These studies provide very useful information in the policy making process. However, they do not give us a measure of whether a change results in an economy being better off or worse off – additional GDP (or GSP) creates some benefits, but usually, some costs as well. Ultimately, if one is to determine whether a policy makes the economy better or worse off, there needs to be a measure of net benefits or costs.

There are two ways in which this can be done. Cost benefit analysis (CBA) is specifically designed to assess net costs and benefits, or welfare. More recently, CGE models, which provide a means of assessing a range of impacts, have been used to assess net costs and benefits. The two methods provide, in principle, the same answer to the question- “is the economy better off” as a result of a policy. However, both methods involve approximations – CBA is mainly a partial equilibrium approach, and it misses out on measuring general equilibrium effects, whereas CGE models as used are typically more aggregative and miss out on detail.

It is a straightforward matter to include a net benefit measure in a CGE model, and in some countries this is now being done regularly. This means that CGE models can be used to assess whether the country is better off or not as a result of a policy-there is no need to rely on inaccurate and misleading proxies, such as the impact on GDP or consumption, which are often used in Australia and in other countries.

Below, we examine four policy problems each of which have been addressed by the CEP:

- • Measuring the costs and benefits of promotion

- • Evaluating events

- • Evaluating airline liberalisation

- • Assessing aviation taxes

4.2. The costs and benefits of tourism promotion

As noted above, the CEP made an estimate of the impact of tourism promotion on the Australian economy ( Dwyer et al., 2014 ). The next stage would be to assess the net benefits and costs of this promotion. The Australian government's main micro economic adviser, the Productivity Commission, called for this to be done, though it did not recommend how best to do this ( Productivity Commission, 2015 ). So far as we are aware, this type of exercise has not been done to date for Australia or any other country. However, based on the research done by CEP, it is a straightforward matter to do it.

There are two key rationales for government support for destination promotion. One is that there is a public good aspect to promotion. Most firms are not able to promote effectively in national or global markets and thus decline to help fund it (the free rider problem). The second is less commonly advanced, and it relies on the existence of distortions in markets, such as taxes. When tourists visit a destination, they spend money and the destination gains a benefit when this expenditure is taxed. The benefits associated with the first rationale are very difficult to measure, though those stemming from the second can be measured easily. Benefits from promotion cannot readily be assessed using the normal tools of CBA, given that there are myriad effects spread throughout the economy. However, these benefits are straightforward to assess using the CGE approach.

A “cost-benefit” calculation can be done using a CGE model. This involves measuring the impact of promotion spending on tourism spending (see above) and determining the net benefit from this spending. This can be compared to the net cost of the promotion, and benefit-cost ratio can be estimated (see Forsyth, 2015 ).

To show this, an example of a submission to a Productivity Commission Research Report by Australia's national tourism marketing body, Tourism Australia, on the impact of the agency's promotion spending on visitor expenditure, is used ( Tourism Accommodation Australia, 2014 ). If we take account of the fact that additional spending on promotion also entails a marginal welfare cost of taxation of 1.275 per $1 to fund the spending, plus an administrative margin of 0.25 of the promotion spending, this leads to a cost per $ of promotion spending of 1.59 ($1.l275 × 1.25) The only change required from the Tourism Australia estimate is then to replace the estimated economic impact (an additional $15 of tourism expenditure) with the net benefit or welfare change from tourism-this has been estimated by the CEP as 13.5% of the expenditure. Using the CEP estimate that an additional $1 of tourism expenditure would yield benefits of $2.025 ($15 × 0.135), a $1 of promotion spending would cost $1.59 to produce a net benefit of $2.025, yielding a net cost-benefit ratio of 1.27 Different parameters would give rise to different estimates of this cost-benefit ratio-however, the important result is that a CBA of tourism promotion, as called for by the Productivity Commission, indicates that the promotion spending remains a worthwhile investment.

It should be noted that this is a partial measure of the benefits from promotion, since there is no allowance for the “public good” rationale for promotion. These are rough calculations, though they do indicate that the type of cost-benefit calculations are eminently feasible, though only by using a CGE approach. More rigorous examination of the returns to promotion is warranted. The approach taken by the CEP has application worldwide.

4.3. Event evaluation

As discussed above, CEP was one of the earliest users of CGE models in event evaluation-in particular, in relation to evaluating the impact of events. It did not go further and assess the net benefits of events themselves, though it did contribute to the literature on benefit measurement. In spite of the importance of measuring benefits for policy purposes, there has been little research in this area, in Australia or elsewhere. There has been some use of CGE models which include a net benefit or welfare measure elsewhere, notably by Blake in a pre-event study of the London Olympics ( Blake, 2005 ). There has also been some use of CBA in event evaluation ( ACT Auditor General, 2002 , Victorian Auditor-General Office, May 2007 ). Interestingly, the latter study also included a CGE study of the same event-however, it was only an impact study, and the two studies' results are not comparable.

A current area of research concerns the relative merits of CBA and CGE models as a means of evaluating events. The comparison has been discussed in work by CEP ( Dwyer, Jago, & Forsyth, 2016 ), Abelson (2011) and the Productivity Commission (2015) . The Commission's Report takes a strong line on the appropriate way of evaluating events-it prefers CBA and says that all the methods are not appropriate.

There are some event specific limitations which arise when using CBA. Most events draw visitors from outside the region, state or country. If these visitors are incurring expenditures, how can the benefits or costs to the home economy be measured? CBA has no answer to this question, other than by making arbitrary assumptions. A CGE approach can, data permitting, do a complete evaluation when combined with approaches to value event related social and environmental impacts. The problem of integrating CGE modelling and CBA in event evaluation remains unresolved despite its importance to event assessment worldwide.

4.4. Airline liberalisation

International airlines are both export services industries, and import competing industries-the two need to be taken together. Most international airline routes are regulated on a bilateral basis. This often means that if a country is asked to allow a foreign owned airline to have more capacity, it will expect more capacity for its own airlines. Imports and exports will be jointly determined. In reality, there tends to be situations where a country, Australia for example, is the net exporter of airline services (e.g. to the US) and others where it is a net importer (e.g. from the UAE).

Another relationship which is important is the complementary one between international aviation and tourism. Efficient international aviation increases the benefits from tourism. The Productivity Commission (2015) , in its recent report on tourism, calls for “transparent cost-benefit analysis” to be used when liberalisation is being considered, such as when additional capacity is being “granted” to a country's airlines to fly to Australia. Both CBA and CGE approaches can be used to evaluate liberalisation. However, one limitation of CBA is that it does not have a rigorous way of measuring the benefits and costs of inbound and outbound tourism ( Forsyth, 2006 ).

In a study of the benefits and costs of airline liberalisation for Australia undertaken by CEP ( Forsyth & Ho, 2003 ), the starting point was a CBA study done by the Productivity Commission in 1998. This study did not measure any benefits or costs of inbound and outbound tourism, though it did include other costs and benefits, and it recognised that tourism benefits should be included. The CEP CGE model was used to make estimates of the benefits from inbound tourism, along with the costs of outbound tourism. This was done for a number of air transport markets in Asia, including the important Australia–Japan market. The result was a total measure of all the costs and benefits from liberalisation. Liberalisation was positive for several markets, though not all. In the Japan market, Australia gained more from inbound Japanese tourism than it lost from outbound tourism, but overall, liberalisation was not positive (other factors outweighing the tourism benefits). This is an example of using a CGE model to fill in the gaps which are left by a CBA study and the approach can be applied worldwide.

4.5. The Passenger Movement Charge

As discussed above, The Passenger Movement Charge (PMC), levied on all outgoing passengers from Australia, is a barrier to tourism exports. The important question should be – does Australia gain from having this barrier? There have been many studies of equivalent taxes, such as the UK APD, and studies, invariably based on Economic Impact Analysis (EIA), which conclude that they are harmful to the country imposing them. A study of the PMC in Australia, also based on EIA, concludes that it is harmful to Australia ( IATA, 2013 ).

A study undertaken by CEP, however, came to a radically different conclusion regarding the effects of the PMC ( Forsyth et al., 2014 ). This study, as noted above, used a CGE approach, taking into account the “tax exporting” aspect of the PMC. In effect, a country gains if it can export its taxes, i.e., get nationals of other countries to pay them. This is an example of the “optimal tariff” argument, in that Australia can use its market power in the tourism market to raise its prices.

Beyond estimating the economic impacts, to assess whether a country gains or loses from imposing a tourism tax such as the PMC, a cost-benefit calculation needs to be done. On the one hand there are the revenue effects, which are positive for the country since they involve substituting taxes paid by its nationals by taxes paid by foreigners. On the other hand, there is a loss of tourism benefits from inbound tourism, as well as a possible gain or loss from lower outbound tourism (usually a gain). Given that the reduction in gains from inbound tourism are small relative to tourism expenditure (the figure of 13.5% was used in the discussion of promotion above), it is not surprising that Australia gains from imposing the tax. It may not be efficient from a global perspective, but it makes sense for an individual country like Australia. Forsyth et al. (2014) also examined the effects on the Australian tourism industry-unlike the nation as a whole, the tourism industry loses.

There are ways in which the PMC can be changed. It would be possible to gain more revenue at less cost to the tourism industry by a change to its structure. Another possibility involves linking revenue to tourism promotion. While there are downsides to earmarking revenues from taxes, it may be worthwhile considering an arrangement whereby additional revenue from the PMC would be used for tourism promotion, thereby creating a benefit for the tourism industry and increasing the gains from tourism exports.

5. Conclusion

In all, engagement with industry and government formed a very large part of the work of the CEP over most of the life of the STCRC. This was reflected in a constant stream of meetings, workshops, presentations and reports which were given to a very wide range of industry and government bodies, generally at their invitation and frequently in active cooperation with them. These included the national and all of the eight state and territory governments, tourism industry representative bodies (including Tourism Council of Australia (TCA) and Tourism and Transport Forum (TTF), government research agencies) (Tourism Research Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Productivity Commission, destination marketing and management agencies such as Tourism Australia, Destination New South Wales, Events New South Wales), and their equivalents in other states. CEP also regularly met with major industry stakeholders such as Qantas which sponsored a University chair for 7 years to support the CEP modelling effort. This role was always seen as integral to the work of the CEP in support of the prescribed role of CRCs as a catalyst for enhancing collaboration between university researchers and industry and government.

The STCRC ceased to exist in 2010, and with it, the funding necessary to support the wider CEP research agenda. At a time when productive interactions between modellers and users and associated learning effects, seems to characterise an increasing volume of policy analysis on a wide range of topics, it is disappointing that Australian tourism has gone in the reverse direction. There are lessons for other destinations beyond the analytical techniques developed by the CEP-the approach of CEP to industry and government engagement and the policy evaluation tools developed, is one that could be emulated in other destinations for the benefit of all tourism stakeholders.