- Where We Work

Tanzania Economic Update: How to Transform Tourism into a More Sustainable, Resilient and Inclusive Sector

Stone Town, Zanzibar

Photo credit: Christian Morgan/World Bank.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- The latest Tanzania Economic Update highlights the huge untapped potential of the tourism sector to drive the country’s development agenda

- The new analysis discusses long-standing issues facing tourism in Tanzania as well as new challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic

- The report says that the pandemic offers an opportunity for policy actions for the sector to recover in the near term and become a sustainable engine of private-sector-driven growth, social and economic inclusion, and climate adaptation and mitigation over the long term

DAR ES SALAAM, July 29, 2021— Tourism offers Tanzania the long-term potential to create good jobs, generate foreign exchange earnings, provide revenue to support the preservation and maintenance of natural and cultural heritage, and expand the tax base to finance development expenditures and poverty-reduction efforts.

The latest World Bank Tanzania Economic Update, Transforming Tourism: Toward a Sustainable, Resilient, and Inclusive Sector highlights tourism as central to the country’s economy, livelihoods and poverty reduction, particularly for women, who make up 72% of all workers in the tourism sector.

“Without tourism, the situation would be bad,” said Rehema Gabriel, a hotel attendant in Dar es Salaam. “I have been working in the tourism industry for eight years now, so I do not know what it would be like without it.”

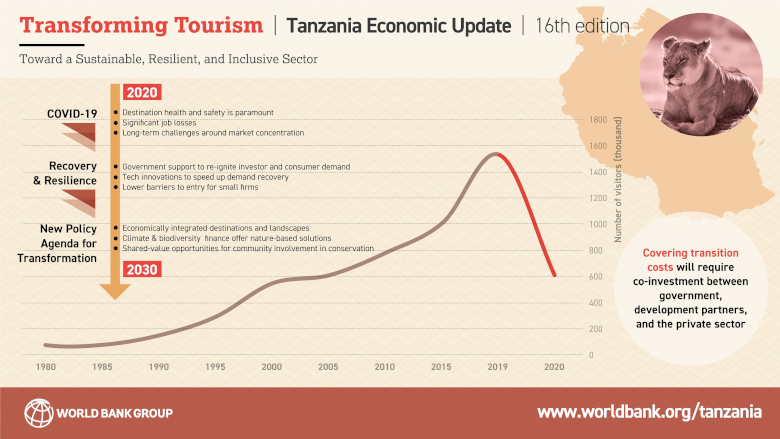

The economic system around tourism had grown in value over the years and in 2019 was the largest foreign exchange earner, the second largest contributor to the gross domestic product (GDP) and the third largest contributor to employment, the report says. On the semiautonomous Zanzibar archipelago, the sector has also experienced rapid growth, accounting for almost 30% of the island’s GDP and for an estimated 15,000 direct and 50,000 indirect jobs. However, the report notes, only a small fraction of Tanzania’s natural and cultural endowments has been put to economic use through tourism development.

“Tourism offers countries like Tanzania, with abundant natural and cultural endowments, access to many foreign markets,” said Shaun Mann, World Bank Senior Private Sector Development Specialist and co-author of the Tanzania Economic Update. “But the absence of tourism revenues, as we have seen during this pandemic, compromises the integrity and viability of not only endowments, but also the economic, environmental and social ecosystems built up around those endowments.”

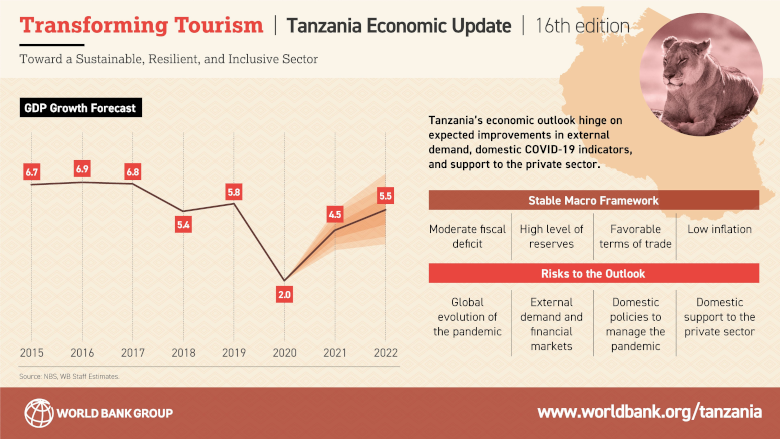

Amid the ongoing COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic, the World Bank estimates that Tanzania’s GDP growth decelerated to 2.0% in 2020. Business slowed across a wide range of sectors and firms, especially export-oriented sectors such as tourism and manufacturing. The report highlights the impact of the crisis on tourism specifically, which has had consequences beyond just the industry, given the many other sectors that support, and are supported by, tourism. The 72% drop in the sector’s revenues in 2020 (from 2019 levels) closed businesses and caused layoffs.

Zanzibar’s economy was even more severely impacted with GDP growth slowing to an estimated 1.3%, driven by a collapse of the tourism industry. As the hospitality industry shut down between March and September 2020, occupancy rates dropped to close to zero. While the Zanzibar tourism sector started slowly rebounding in the last quarter of 2020, with tourist inflows in December 2020 reaching almost 80% of those in 2019, receipts from tourism fell by 38% for the year.

As the tourism sector transitions gradually into recovery mode with the rest of the world, the report urges authorities to look toward its future resilience by addressing long running challenges that could help position Tanzania on a higher and more inclusive growth trajectory. Areas of focus include destination planning and management, product and market diversification, more inclusive local value chains, an improved business and investment climate and new business models for investment that are built on partnership and shared value creation.

Tanzania is a globally recognized destination for nature-based tourism, a competitive market segment in eastern and southern Africa. Beyond attracting tourists, the country’s landscapes and seascapes produce a wide range of ecosystem services, including carbon sequestration and biodiversity co-benefits that are not efficiently priced and often generate little or no financial return. The global climate crisis has created significant demand for investment in these forms of natural capital, and Tanzania is well positioned to take advantage of nature-positive investment opportunities. The additional revenue derived from global climate programs could be an opportunity to ease the government’s fiscal constraints while also supporting the livelihoods of local communities.

“While restoring the trade and financial flows associated with tourism is an urgent priority, the disruption of the sector has created an opportunity to realign tourism development with economic, social, and environmental resilience,” said Marina Bakanova, World Bank Senior Economist, and co-author of the report. “The pandemic has created an opportunity to implement long-discussed structural reforms in the sector and use tourism as a leading example of improvement of the overall business climate for private investment.”

The authors suggest five priorities for a sustainable and inclusive recovery that lay the foundation for the long-term transformation of the tourism sector:

- Creating an efficient, reliable, and transparent business environment to reduce red tape and multiple distortions and inefficiencies, hindering decisions on private investments, domestic and foreign

- Establishing an information-management system that consolidates data from tourists and firms, enabling policymakers to improve sectoral planning and identify viable investment opportunities

- Ensuring that firms across the sector, as well as those in downstream value chains, have access to affordable transitional finance

- Consistently promoting, monitoring, and reporting on adherence to health and safety protocols.

- Developing co-investment and partnership arrangements to support nature-based landscape and seascape management

- Press Release: Tanzania has an Opportunity to Ignite Inclusive Economic Growth by Transforming its Tourism Sector

- Report: 16th Tanzania Economic Update: ‘Transforming Tourism: Toward a Sustainable, Resilient, and Inclusive Sector’

- Video: Launch event: 16th Tanzania Economic Update

- The World Bank in Tanzania

- The World Bank in Eastern and Southern Africa

- The World Bank in Africa

- Africa Collective

Business Insider Edition

- United States

- International

- Deutschland & Österreich

- South Africa

Tanzania eyes tourism growth to boost economy in 2024

Tanzania's tourism sector could potentially generate up to Sh3.38 trillion in additional revenue in the next financial year from Sh2.38 trillion in the current financial year, a senior official said on Tuesday.

Tanzania's tourism industry is making a remarkable comeback nearly four years after its revenues plummeted due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The tourism sector could potentially generate up to Sh3.38 trillion in additional revenue in the next financial year, according to a senior official.

- Enhancing the business climate and expanding projects are some of the factors that could greatly boost revenue collection.

Recommended articles

The Principal Secretary in the Ministry of State, Office of the President, Finance and Planning, Dr Juma Maliki Akili, disclosed this at the ‘2024/2025 Economy and Budget annual forum’ for stakeholders from local government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

While addressing the gathering at the Sheikh Idriss Abdulwakil Multipurpose Hall, Dr Akili explained that the revenue collection until the end of the current financial year, which ends in June this year, is projected to hit Sh2.38 trillion.

He added that the figure could significantly increase as a result of factors such as enhanced dedication from stakeholders in tax compliance and encouragement of voluntary tax contributions, intensified efforts by the Zanzibar Revenue Authority (ZRA) and Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA), along with robust collaboration between the authorities and principal institutions.

“We predict to have economic growth of 7.2 per cent next year, and our revenue collection may increase to Sh3.38 trillion, while the number of tourists will increase to 829,000 next year from 638,000, ending the financial year,” Dr Akili said, according to Daily News .

Dr Akili expressed confidence that the target would be achieved, stating that in 2019, economic growth slowed down due to COVID-19 and that good planning has helped Zanzibar recover.

According to him, increasing knowledge about tax among ZRA and TRA staff, improving the business/investment environment, increasing projects, and increasing production from the blue economy are added advantages to an admirable bright future for Zanzibar.

Last year, data from the Bank of Tanzania revealed that tourism has staged an impressive recovery, contributing $2.99 billion to foreign exchange earnings in July 2023, compared to $1.95 billion in July 2022.

The bank also noted that this resurgence in tourism and increased earnings from gold have played a pivotal role in boosting Tanzania's service earnings to over $5 billion for the first time in its history.

FOLLOW BUSINESS INSIDER AFRICA

Thanks for signing up for our daily insight on the African economy. We bring you daily editor picks from the best Business Insider news content so you can stay updated on the latest topics and conversations on the African market, leaders, careers and lifestyle. Also join us across all of our other channels - we love to be connected!

Top 10 Bitcoin casinos for US players: Comparing the best crypto casinos

10 best online slots usa: top slots sites to play for real money (usa), fastest payout online casinos: top 10 instant withdrawal casinos in 2024, 10 wealthiest countries in africa, 5 african countries with the highest schengen visa rejection rates, top 10 african countries with the strongest governments, oluwatomi solanke shares trove finance's journey of pioneering micro-investment in nigeria, beyond diagnostics: the expanding role of medical laboratories in west africa, president ruto seems to be winning the goodwill of his people.

Resource-poor African countries set to outperform resource-rich nations

Elon Musk's Starlink asked to halt services in Zimbabwe over licensing

Nigeria LNG Limited (NLNG) faces arbitration hurdles as Shell tables claims against Venture Global LNG over unsuppplied cargoes

J&j cough syrup recall widens as tanzania, rwanda, zimbabwe join efforts.

Tanzania's tourism revenue surpasses that of pre-pandemic period

Tanzania earned $3.3 billion from tourism receipts in the year ending November 2023 compared to $2.4 billion a year earlier, according to data released by the country’s central bank.

The Bank of Tanzania said the increase in travel receipts reflects the rebound of the tourism sector, as tourist arrivals rose by 27% to about 1.8 million.

The tourism industry was in a state of recovery following the COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted worldwide travel bans to prevent the virus from spreading further.

Tanzania's tourism receipts dropped to $1 billion in 2020 and $1,2 billion in 2021 from the pre-pandemic earnings of $2,5 billion in 2019.

The East African nation aims to attract 5 million visitors and generate $6 billion in tourism-related revenue by the year 2025.

- Featured News

- Stock Market

- Agriculture

- Construction

- Financial Services

- Information Technology

- Infrastructure

- Manufacturing

- Real estate

- Telecomunication

- Transportation

Tanzania eyes $6 billion in revenue from tourism sector by 2025

Tanzania’s tourism accounts for more 17 per cent of GDP and 25 percent of foreign earnings and possesses significant potential to contribute to the national economy and foreign receipts because of the unique natural attractions present in the country.

The tourist attractions present in Tanzania include national parks and game reserves, forests, mountains, valleys, waterfalls, and coastal areas among others.

To promote sector competitiveness and linkages, FYDP III is prioritizing the development and implementation of a clear tourism legal and regulatory frameworks and strengthening public-private dialogue and collaboration.

Key Interventions include promoting new tourism products, development and diversification for sustainable growth; promote southern tourist circuit as alternative to other circuits.

Speaking during the just ended Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency [MIGA] investment forum held in Dar es Salaam, the Tanzania Tourist Board’s Acting Director General Felix John said that a wake to enhance and market Tanzania’s tourism endowments, President Samia Suluhu Hassan initiated the Royal Tour Programme.

The Program is aligned to the country’s Five Years Development Plan (2021/22 – 2025/26) that targets on increasing the number of tourists visiting destination Tanzania to reach 5 million tourists and revenue generated from the Sector to reach 46 billion by 2025.

The Royal Tour Programme was officially launched in April, 2022 in the United States of America (New York and Los Angeles) which is one of our principal source markets, and since then it started to bear fruits with the number of both domestic and international tourists increasing tremendously compared to the previous period.

Explaining the trends of tourism in Tanzania the TTB boss said that the number of visitors’ arrival has risen to 922,692 in 2021 from 620,867 in 2020 after it aftermath dropped due to the aftermath of the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Revenue generated from the Sector also rose from $714.59 million in 2020 to $1.31 billion in 2021.

On his part, the Minister for Finance and Planning Dr Mwigulu Nchemba said the launched Royal Tour film aims at showcasing opportunities available in Tanzania’s tourism sector as well as investment opportunities in other sectors.

“I would like to invite the diaspora and investors from all over the world to visit Tanzania as well as investing in various opportunities. Our aim to promote private sector investment.” He stressed.

Dr Nchemba further noted that the government was committed to transform Tanzania to be a hub and model of strategic and attractive investments destination.

Daniel Semberya

Tanzania Chamber of Commerce recognized at Small Business Champions Initiatives Awards

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Exchange Rate

Exchange Rate USD : Wed, 17 Apr.

Recommended

Global demand for lithium batteries to leap five-fold by 2030

NMB Bank CEO Ruth Zaipuna featured on Africa.com’s 2023 Definitive List of Women CEOs

Popular news.

Get latest news from us. SUBSCRIBE

- Commodities

- Q&A Interviews

The Business Wiz (TBW) is Tanzania’s premier one-stop online platform providing in-depth, accurate and timely business news, analysis, commentary and online business information portals and research.

© 2022 The Business Wiz

- Economy & Politics ›

- Tourism receipts in Tanzania from 2020-2022

Tourism receipts in Tanzania from 2020 to 2022 (in million U.S. dollars)

Additional Information

Show sources information Show publisher information Use Ask Statista Research Service

2020 to 2022

year ending April

Other statistics on the topic

Geography & Nature

- Highest mountains in Africa

Travel, Tourism & Hospitality

- International visitors in Zanzibar 2015-2021

- Main countries of origin of international visitors in Zanzibar 2021

- Tourist arrivals in Tanzania 2015-2022

- Immediate access to statistics, forecasts & reports

- Usage and publication rights

- Download in various formats

You only have access to basic statistics.

- Instant access to 1m statistics

- Download in XLS, PDF & PNG format

- Detailed references

Business Solutions including all features.

Statistics on " Travel and tourism in Tanzania "

- International tourist arrivals in Africa 2020, by country

- Monthly tourist arrivals in Tanzania 2019-2022

- Main nationalities of tourists arriving in Tanzania 2021

- Average tourist expenditure in Tanzania 2015-2020

- Contribution of travel and tourism to GDP in Tanzania 2019-2021

- Value added of travel and tourism to GDP in Tanzania 2019-2021

- International and domestic visitor spending in Tanzania 2019-2021

- Share of employment in travel and tourism in Tanzania 2019-2021

- Highest-rated safari parks in Africa 2021

- World Heritage Sites in Africa 2021, by country

- Most visited national parks in Tanzania 2019

- Revenue generated by visits to national parks in Tanzania 2015-2019

- Visitors at national parks in Tanzania 2020-2021, by geographical zone

- Earnings from visitors at tourist attraction sites in Tanzania 2021, by zone

- Hotel occupancy rate in Africa 2021-2023

- Bed occupancy rate of hotels in Tanzania 2019-2020

- Number of tourists staying in hotels in Tanzania 2015-2020

- Bed nights occupied in hotels of Tanzania 2019-2020

- Share of international visitors in hotels occupancy in Tanzania 2020

- Monthly international arrivals in Zanzibar 2018-2021

- Hotel beds available in Zanzibar 2020-2021

- Bed occupancy rate in Zanzibar 2020-2021

- GDP of hotels and food services in Zanzibar 2016-2020

- Share of hotels and food services in Zanzibar's GDP 2016-2020

Other statistics that may interest you Travel and tourism in Tanzania

- Premium Statistic International tourist arrivals in Africa 2020, by country

- Premium Statistic Tourist arrivals in Tanzania 2015-2022

- Premium Statistic Monthly tourist arrivals in Tanzania 2019-2022

- Basic Statistic Main nationalities of tourists arriving in Tanzania 2021

- Premium Statistic Average tourist expenditure in Tanzania 2015-2020

Economic impact

- Basic Statistic Contribution of travel and tourism to GDP in Tanzania 2019-2021

- Basic Statistic Value added of travel and tourism to GDP in Tanzania 2019-2021

- Basic Statistic Tourism receipts in Tanzania from 2020-2022

- Basic Statistic International and domestic visitor spending in Tanzania 2019-2021

- Basic Statistic Share of employment in travel and tourism in Tanzania 2019-2021

Attractions

- Premium Statistic Highest-rated safari parks in Africa 2021

- Basic Statistic Highest mountains in Africa

- Basic Statistic World Heritage Sites in Africa 2021, by country

- Premium Statistic Most visited national parks in Tanzania 2019

- Premium Statistic Revenue generated by visits to national parks in Tanzania 2015-2019

- Basic Statistic Visitors at national parks in Tanzania 2020-2021, by geographical zone

- Basic Statistic Earnings from visitors at tourist attraction sites in Tanzania 2021, by zone

Accommodation

- Premium Statistic Hotel occupancy rate in Africa 2021-2023

- Premium Statistic Bed occupancy rate of hotels in Tanzania 2019-2020

- Premium Statistic Number of tourists staying in hotels in Tanzania 2015-2020

- Premium Statistic Bed nights occupied in hotels of Tanzania 2019-2020

- Premium Statistic Share of international visitors in hotels occupancy in Tanzania 2020

Special focus: Zanzibar

- Premium Statistic International visitors in Zanzibar 2015-2021

- Premium Statistic Monthly international arrivals in Zanzibar 2018-2021

- Premium Statistic Main countries of origin of international visitors in Zanzibar 2021

- Premium Statistic Hotel beds available in Zanzibar 2020-2021

- Premium Statistic Bed occupancy rate in Zanzibar 2020-2021

- Premium Statistic GDP of hotels and food services in Zanzibar 2016-2020

- Premium Statistic Share of hotels and food services in Zanzibar's GDP 2016-2020

Further related statistics

- Premium Statistic Loss of global travel bookings from China for March and April 2020, by region

- Premium Statistic Impact on the coronavirus on tourist overnight stays in Italy 2020, by region

- Premium Statistic Export value of miscellaneous services Philippines 2018-2023

- Basic Statistic Healthcare businesses expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Basic Statistic Accommodation and food services expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Basic Statistic Arts and recreation businesses anticipating COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Basic Statistic Telecommunications businesses expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Premium Statistic Export value of government services Philippines 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Services export value from Russia to APAC 2010-2019

- Basic Statistic Retail trade businesses expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Premium Statistic Forecasted real GDP growth rate due to COVID-19 G7 countries Q2 2020

- Premium Statistic External debt stock in Sub-Saharan Africa 2016-2020

- Premium Statistic Number of private sector employees in constructions in Tunisia 2003-2020

- Basic Statistic Government expenditures in Egypt 2016-2023

Further Content: You might find this interesting as well

- Loss of global travel bookings from China for March and April 2020, by region

- Impact on the coronavirus on tourist overnight stays in Italy 2020, by region

- Export value of miscellaneous services Philippines 2018-2023

- Healthcare businesses expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Accommodation and food services expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Arts and recreation businesses anticipating COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Telecommunications businesses expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Export value of government services Philippines 2020-2022

- Services export value from Russia to APAC 2010-2019

- Retail trade businesses expecting COVID-19 impacts Australia 2020 by type

- Forecasted real GDP growth rate due to COVID-19 G7 countries Q2 2020

- External debt stock in Sub-Saharan Africa 2016-2020

- Number of private sector employees in constructions in Tunisia 2003-2020

- Government expenditures in Egypt 2016-2023

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Tourism doing business.

Business Investing

- Investing in Albania

- Investing in Uruguay

- Investing in Ecuador

- Investing in Chile

- Investing in Mozambique

- Investing in Uzbekistan

- Investing in Mauritius

- Investing in Paraguay

- Investing in Dominican Republic

- Investing in Colombia

- Investing in United Republic of Tanzania

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Investing in the United Republic of Tanzania

"With an increased focus on green investments, the United Republic of Tanzania has a great potential to seize on these opportunities and formulate a value proposition based on these comparative advantages"

Zurab Pololikashvili, UN Tourism Secretary-General

Introduction

In an effort of the continuous series of Tourism Doing Business reports , the UN Tourism is proud to have coordinated efforts with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (MNRT), the Tanzania Investment Centre (TIC) and the Zanzibar Investment Promotion Authority (ZIPA) to create this tool to promote investments in the United Republic of Tanzania. This publication builds a reference for investors by providing valuable information and guidance on the United Republic of Tanzania’s current investment climate as well as emerging investment opportunities in its tourism sector.

With a population of almost 60 million inhabitants, the United Republic of Tanzania has a relatively stable political environment, sound macroeconomic policies and a clear resilience to external shocks. After experiencing a strong growth in recent years, the country’s growth rate of GDP slowed down over the past two years due to the detrimental consequences of COVID-19. Nevertheless, the United Republic of Tanzania’s GDP grew at 4.90% in 2021 whilst the global economic recovery rebooted and experts forecast that economic growth will pick up again from 2022 with an estimation of 5% of GDP growth.

The United Republic of Tanzania demonstrates a very promising investment environment with a strong growth potential of its nature-based tourism sector. Indeed, growing on average at 6.5%, per year the United Republic of Tanzania of has demonstrated an impressive growth performance and stability over the past decade. Also, between 2015 and 2021, the country experienced a marginal increase of its GDP per capita of 24.15%, growing from USD 981 million to USD 1,218 million. Consequently, the United Republic of Tanzania positioned itself as one of the most preferred destinations for foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa and among the 10 biggest recipients of FDI on the continent. FDI inflows in the United Republic of Tanzania rose by 35 % from USD 685 million in 2020 to USD 922 million in 2021, and new greenfield project announcements tripled in value.

On the other hand, with its abundance of natural and cultural resources, the United Republic of Tanzania has gained international recognition for its nature-based tourism in Africa and the world. The Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index by the World Economic Forum ranked the United Republic of Tanzania 1st in Africa and 12th worldwide regarding the quality of its nature-based tourism resources as well as 32nd in Africa vis-à-vis its cultural resources. As a result, the tourism value chain defines a key component of the United Republic of Tanzania’s economy today, contributing to an estimated 17% of the country’s GDP and building the country’s third-largest source of employment by directly employing over 850,000 workers. Tourism-related services are especially crucial in Zanzibar, accounting for 55.5% of total services output, and for more than half of Zanzibar’s GDP, generating the largest share of private-sector employment. This said, tourism has been among the largest foreign-exchange earners in the United Republic of Tanzania since 2012. According to data from UN Tourism, tourism accounted for over one-quarter of the country’s foreign-exchange earnings in 2019, representing around USD 2,605 million. In addition, the latest report by fDi Intelligence from the Financial Times and UN Tourism ranked the United Republic of Tanzania, with nine projects, among the top 10 countries in Africa and the Middle East with the greatest number of greenfield investments in the tourism sector.

Conclusions

- The United Republic of Tanzania has been attracting international investments and increasing its inflows in the last decade, which positioned the country among one of the top destinations for tourism investments in the African continent. However, the country should continue implementing its efforts to improve its business enabling environment. This might involve strengthening institutions, regulations, policies, and transparency frameworks that facilitate the attraction and promotion of investment inflows towards the tourism sector and its value chain. Consequently, this will improve the country’s investment climate and encourage the development of strategic partnerships between government, and the private sector.

- The United Republic of Tanzania is known for its rich biodiversity, wildlife attractions, and cultural resources. The country is home to several nature reserves and national parks and represents a unique tourist destination for thousands of tourists each year. Henceforth with an increased focus on green investments, the United Republic of Tanzania has a great potential to seize on these opportunities and formulate a value proposition based on these comparative advantages. In addition, when considering new emerging consumer behaviors focused on sustainable and rural tourism demand the United Republic of Tanzania may create strategic investment opportunities for conservation, climate finance, and green investments to further diversify, attract and mobilize international and private investments. Likewise, improving the country’s regulatory mechanisms and incentives concerning climate change mitigation and adaptation as well as conservation efforts will help foster green investments to ensure the environmental, social, and economic development of its destination and safeguard its natural and cultural resources.

- Finally, the United Republic of Tanzania might consider developing new incentives and investment mechanisms to strengthen and expand its tourism value chain and supply of tourism services. The COVID-19 pandemic has tremendously harmed the tourism sector, most severely affecting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) within the tourism value chain. According to the World Bank, the United Republic of Tanzania experienced a 72 % drop in tourism revenue between 2019 and 2020. To guarantee a more resilient, innovative, and sustainable tourism sector particularly digitalization and innovation among SMEs are critical and SMEs must apply strategies to upskill and train their employees. Moreover, the United Republic of Tanzania may also promote programs and opportunities for innovations through the incorporation of travel and tourism startups to facilitate the diffusion of new technologies and increase inflows of new capital for diversification.

- Tourism Doing Business - Investing in United of Republic of Tanzania (PDF)

- Presentation - Tourism Doing Business Investing in United of Republic of Tanzania

Tanzania Exports Up by 14.7% in The Year Ending February 2024, Tourism Receipts Up by 28.5%

Vodacom Tanzania Acquires Smile Communication Tanzania

Ecobank Group Best Bank for SMEs in Africa

Tanzanian Bank and Mobile Operator Forge Partnership to Facilitate Smartphone Financing

Tanzania economic review, september 2023: tourism and transport receipts up by 30.5%.

The Bank of Tanzania (BOT) released its Monthly Economic Review-October 2023 which covers key macroeconomic indicators for the year ending September 2023.

Table of Contents

External Sector Performance

The external sector continues to battle with challenges arising from an unhealthy global economic environment.

Nevertheless, the deficit in the current account balance narrowed to USD 3,383.4 million in the year ending September 2023, compared with USD 4,728.2 million in the preceding year.

The outturn was on account of increased seasonal earnings from tourism activities and traditional exports.

Foreign Exchange Reserves

The foreign exchange reserves stock fell to USD 4,880.4 million from USD 4,961.5 million at the end of September 2022, largely credited to the payment of foreign obligations by the Government.

Despite the decrease, reserves were adequate to cover 4 months of projected imports of goods and services, within the country’s benchmark.

The export of goods and services showed an upward trend for three years in a row , rising by 16.1% in the year ending September 2023 to USD 13,414.8 million from the level recorded in the preceding year.

The performance was largely contributed by travel receipts and non-traditional exports, in particular minerals ( gold and coal ).

Non-traditional Goods and Mineral Exports

Export of non-traditional goods grew by 6.4%, from USD 572.9 million to USD 594.4 million.

The value of gold exports rose by +7.4% to USD 2,983.8 million up from USD 2,777.2 million in the year ending September 2023, driven by volume and price effects.

Coal exports amounted to USD 206.1 million from USD 111.7 million in the previous year, owing to increasing demand in the neighboring countries, and in Europe resulting from supply shortages associated with the war in Ukraine.

Improvement is also observed in horticultural exports , particularly vegetables.

Traditional Exports

Export of traditional goods increased by 13.9% to USD 853.9 million from USD 749.5 million, driven by tobacco and coffee exports.

On a monthly basis, traditional goods worth USD 124.1 million were exported compared with USD 78.2 million in a similar month in 2022.

Service and Tourism Receipts

Service receipts increased by 30.5% to USD 5,749.2 million in the year ending September 2023 from USD 4,405.5 million in the corresponding period in 2022, mainly resulting from a rise in travel (tourism) and transport receipts.

The surge in travel receipts reflects a steady tourism sector recovery. Tourist arrivals rose to 1,720,501—a record high—from 1,332,709 in the year to September 2022.

On a monthly basis, service receipts were USD 537.1 million in September 2023, compared with USD 407.2 million in September 2022.

- Bank of Tanzania

Sign Up for Our Newsletters

Related posts.

China-Tanzania Investment Forum Strengthens Bilateral Economic Ties With MOUs

Tanzania Exports Up by 14.8% in The Year Ending January 2024

Mwanza Concluded Tanzania Rail Business and Investment Forum

Privacy overview.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Economic impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector in Tanzania

Martin henseler.

a EDEHN – Equipe d'Economie Le Havre Normandie, Le Havre Normandy University, Le Havre, France

b Partnership for Economic Policy (PEP), Nairobi, Kenya

Helene Maisonnave

Asiya maskaeva.

c University of Dodoma, Dodoma, Tanzania

Associated Data

The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has affected the tourism sector by closing borders, reducing both the transportation of tourists and tourist demand. Developing countries, such as Tanzania, where the tourism sector contributes a high share to gross domestic product, are facing considerable economic consequences. Tourism interlinks domestic sectors such as transport, accommodation, beverages and food, and retail trade and thus plays an important role in household income. Our study assesses the macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector and the Tanzanian economy as a case study of an impacted developing economy. We use a computable general equilibrium model framework to simulate the economic impacts resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and quantitatively analysed the economic impacts.

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has severely affected the tourism sector worldwide by closing borders, reducing the transportation of tourists, and decreasing tourist demand. Tourism is the hardest-hit sector. Indeed, in 2020, it was predicted that international tourism would fall by 80% ( OECD, 2020 ). Countries whose tourism sectors contribute a high share to gross domestic product (GDP) are facing considerable economic impact as the tourism sector is an important driver of economic development ( Faber & Cecile, 2019 ; Sinclair, 1998 ), particularly in transitioning and developing countries ( Chou, 2013 ; Khan, Bibi, Lorenzo, Lyu, & Babar, 2020 ; Liu & Wall, 2006 ; Pelizzo & Kinyondo, 2015 ). For example, in Africa, the tourism sector contributes around 9% to real GDP and supports approximately 7% of all jobs. Thus, during the last few decades, the tourism sector has received attention from both tourism researchers and development economists alike ( Brown & Hall, 2008 ; De Kadt, 1979 ; Ghimire, 2001 ; Mings, 1981 ; Rogerson, 2008 ).

In developing countries, where the tourism sector is of high importance to the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant negative impact. First, the pandemic has directly affected the whole economy and society through health consequences and measures against it (e.g., increased hospitalisation and many lethal cases, economic lockdown, closure of schools). Second, the pandemic has impacted the tourism sector in particular, which is very important for economic growth and employment. Third, since tourism is linked to many other economic sectors ( Faber & Cecile, 2019 ; Sinclair, 1998 ), the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector are channelled to linked sectors. These impacts are therefore of high interest to researchers and politicians. The differentiated information on these impacts is relevant for the design of measures and policy decisions in counteracting the negative economic impacts of COVID-19. Particularly in developing countries, which are vulnerable to any economic shock, such information could help support economic growth and reduce the increase in poverty.

Tanzania is a developing country where tourism is a key sector for economic growth ( Antonakakis, Dragouni, Eeckels, & Filis, 2016 ; Curry, 1990 ; Wade, Mwasaga, & Eagles, 2001 ). In 2019, the tourism sector was the second-largest component of GDP, with a contribution of 17%. In terms of employment, the sector is the third-largest source of employment, with 850,000 workers ( World Bank, 2021a ). Moreover, the sector has strong linkages with other domestic sectors such as transport, accommodation, beverage and food, and the retail trade ( Mayer & Vogt, 2016 ). Tourism creates direct and indirect jobs for low and unskilled workers, making it an important driver of economic growth and the fight against poverty ( Pelizzo & Kinyondo, 2015 ). Tourism stimulates domestic and foreign investments in new infrastructure and management of hotels, aviation, training, and travel services, tour operators' businesses, marketing, and promotion of tourism activities ( Mwakalobo, Kaswamila, Kira, Chawala, & Tea, 2016 ). Furthermore, foreign currency earnings from tourism allow for the importation of capital goods that support domestic production ( Brida, Gomez, & Segarra, 2020 ).

Since March 2020, the Tanzanian government has adopted key measures to curb the COVID-19 outbreak ( BOT, 2020 ). These measures have had an impact on all sectors, including the Tanzanian tourism sector, as one of the most important industries for economic growth and employment. The real GDP growth rate declined from 6.9% in 2019 to 4.8% in 2020 owing to regional trade disruptions and contraction in tourism and related sectors as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic ( NBS, 2019b ). Our study assesses the macroeconomic impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector and the Tanzanian economy. We use a dynamic computable general equilibrium model to assess the macroeconomic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector and the Tanzanian economy. Our analysis provides results that will be of interest to researchers and policymakers. (i) We analyse the short and long-term impacts of COVID-19 in Tanzania on the tourism sector, the interlinked sectors, and the macro-economic indicators (e.g., GDP), (ii) we analyse the impacts on labour demand and household income, and (iii) we complement the existing academic literature with a dynamic CGE modelling study on COVID-19 impacts in Tanzania.

2. Literature review

2.1. tourism and computable general equilibrium model studies.

The tourism sector is linked multiple times in the economy to many sectors and economic agents ( Dwyer, 2015 ; Dwyer, Forsyth, & Spurr, 2004 ). It is, therefore, important to capture the links between the tourism sector and the rest of the economy, especially in countries where tourism is important for economic development, as in Tanzania ( Curry, 1990 ; Wade et al., 2001 ). Computable general equilibrium (CGE) models are tools used to assess the impact of external shocks on specific economic sectors, such as tourism, as they consider retroactive effects. The CGE model is applied to analyse the impacts of fiscal policy reforms on tourism in both developed and developing countries (e.g., Ihalanayake, 2012 ; Mabugu, 2002 ; Meng, 2012 ; Ponjan & Thirawat, 2016 ), to evaluate the impacts of investment projects (e.g., Banerjee, Cicowiez, & Cotta, 2016 ), and to assess changes in international commodity markets (e.g. Becken & Lennox, 2012 ; Yeoman et al., 2007 ), or in tourism demand (e.g., Blake et al., 2006 ). Dwyer (2015) and van Truong and Shimizu (2017) present an overview of CGE applications on tourism-related research questions. They conclude that despite its relative suitability, “CGE modelling remains relatively under-used in tourism policy analysis” ( Dwyer, 2015 , p. 124) and that it is even rare in the analysis of specific tourism-related topics like transportation ( van Truong & Shimizu, 2017 ).

In developing countries, the tourism sector has been identified as a potential channel for increasing economic growth and alleviating poverty ( Alam & Paramati, 2016 ; Honey & Gilpin, 2009 ; Khan et al., 2020 ; World Tourism Organization and International Labour Organization, 2013 ). Thus, tourism studies in developing countries often address research questions on economic growth, employment, and income. Several phenomena described in theoretical and empirical studies have also been described in studies using input-output tables or CGE models as analytical frameworks for African case studies.

2.2. Inter-sectoral linkages

Tourism has significant backward linkages to sectors that supply tourists' consumption demand, such as accommodation, restaurants, beverages and food, retail trade, and transport ( Eric, Semeyutin, & Hubbard, 2020 ; Mayer & Vogt, 2016 ; Njoya & Nikitas, 2020 ; Suau-Sancheza, Voltes-Dortac, & Cugueró-Escofeta, 2020 ). Transport and accommodation tourism is indirectly linked to the construction sector, which builds infrastructure for both ( Adam, Bevan, & Gollin, 2018 ; Kweka, 2004 ). In an input-output analysis for Tanzania, Kweka, Morrisey, and Blake (2003) find that tourism can contribute to increasing tax revenue and exchange earnings resulting from the linked sectors. In addition, linkages to natural resource sectors can be highly relevant to the tourism value chain ( Damania & Scandizzo, 2017 ). In agriculture, the tourism sector has relatively weak backward linkages as a traditional sector for exports and subsistence production. Thus, tourism expansion does not necessarily result in income generation for rural farming households. Expansion of tourism can even create a contraction in sectors with weak linkages, caused by sectoral competition for production factors or by the Dutch disease effect ( Kweka et al., 2003 ; Njoya & Seetaram, 2018 ).

2.3. Competition for production factors and Dutch Disease

An expanding tourism sector can compete with other sectors for production factors (e.g., land or labour), resulting in non-tourism sectors being deprived of production factors (e.g., land for agriculture). The sectoral competition for production factors depends on the regional economic situation and the type of tourism. Less labour-intensive tourism often uses intensive natural resources and land (e.g., large-scale resorts, national parks, and safaris) ( Damania & Scandizzo, 2017 ; Karim & Njoya, 2013 ; Njoya & Seetaram, 2018 ). Expanding tourism (as inbound tourism) increases the export of tourism as a service to foreign tourists and thus can change the current account balance and appreciation of the local currency. If the changes in currency appreciation increase the value of the local currency, then the prices of locally produced non-tourism goods and services increase. Becoming more expensive, the traditional exporting sectors (such as agriculture) can lose their competitiveness because relatively cheaper imported products are in high demand. By contracting the production of domestic non-tourism commodities, a growing tourism sector can have negative impacts on the growth of the non-tourism exporting sector(s). Several authors describe these phenomena in Kenya and Tanzania in CGE studies (see Damania & Scandizzo, 2017 ; Jensen, Rutherford, & Tarr, 2010 ; Karim & Njoya, 2013 ; Kweka, 2004 ; Njoya & Seetaram, 2018 ).

2.4. Economic policies

Identified as a pro-growth and pro-poor sector, the support of tourism by economic policies (e.g., taxation, trade reforms or investments) is an interesting research topic in developing countries. However, the impact of economic policies on growth, employment, and poverty can vary between countries, regions, and socioeconomic groups. For example, in their study Gooroochurn and Sinclair (2005) point out that in Mauritius, taxation of tourism sectors or tourists can be more efficient and equitable than levying other sectors and can create a high income for government and households. However, enterprises can suffer income losses if tourist consumption decreases, caused by increased prices from tourists' consumption ( Kweka, 2004 ). The liberalisation of barriers against domestic and multinational service providers in the tourism sector can reduce the production cost of tourism. Thus, trade reform policies could support the expansion of tourism ( Jensen et al., 2010 ).

Investment in transport infrastructure can be a measure to reduce production costs and increase efficiency in the tourism sector, and it has been found that the impacts on poverty and income can be unevenly distributed in the economy. Kweka (2004) describes how investments in transport infrastructure have more positive effects for rural than for urban households. However, Njoya and Nikitas (2020) find in a CGE study that air transport expansion in South Africa creates employment effects with more benefits for wealthy households and highly skilled workers than for poor households and unskilled workers. Thus, investments that should target the alleviation of poverty require caution and good knowledge of the impacts ( Adam et al., 2018 ). To avoid unwanted effects such as widening income inequality, accompanying measures might be required. Such measures could improve education and training for low-skilled workers if highly skilled workers benefit from the positive outcomes of the investment ( Njoya & Nikitas, 2020 ).

2.5. Economic growth

Tourism stimulates domestic production, employment and creates tax income ( Blake, 2008 ; Sharma, 2006 ; Wamboyea, Nyarongab, & Sergic, 2020 ). Indeed, several studies have reported the quantifiable positive effect of tourism on economic development in different African countries: Kenya (e.g., Honey & Gilpin, 2009 ), Mauritius (e.g., Durbarry, 2002 ), Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe (e.g., Manrai, Lascu, & Manrai, 2020 ). Tourism expansion can be initiated by economic policies, but expansion and contraction can also result from the development of economic settings, either from a trend over time or from event-based economic shocks (e.g., catastrophes, terrorist activity, outbreaks of pandemics). Several CGE studies, find that growing inbound tourism created a net benefit to the national economy in Kenya and Tanzania (see Karim & Njoya, 2013 ; Kweka, 2004 ; Njoya & Seetaram, 2018 ). Karim and Njoya (2013) find in Kenya that tourism expansion is pro-growth, particularly for hotels, restaurants, construction, and the agricultural sector. However, there was decreased growth in the manufacturing sector. This finding differs from those of Kweka (2004) and Njoya and Seetaram (2018) , who explain how the expansion of tourism in Kenya and Tanzania caused Dutch disease and a contraction of the agricultural sector as a weakly linked sector for traditional exports.

2.6. Tourism and labour markets

Tourism has many benefits for middle- and upper-income households or tour operators–often foreign owners–while households not linked to tourism attractions (e.g., in rural areas) benefit less ( Eric et al., 2020 ; Kweka, 2004 ). Foreign inbound tourism contributes relatively more to less-skilled wage earners than to high-income workers, making it regarded as pro-poor ( Incera & Fernandez, 2015 ). Thus, in rural regions with tourism activities, tourism can have a positive effect on economic empowerment. Informal jobs allow even women in rural regions to simultaneously engage in childcare and earn money; hence tourism can assist in elevating the social status of women, helping them to afford education, and contribute to household income ( Buzinde, Kalavar, & Melubo, 2014 ). Njoya and Seetaram (2018) show that for Kenya, industries with linkages to the tourism sector increase labour demand in contrast to non-tourism sectors, which has a reverse effect. The demand for unskilled labour increases faster than the demand for skilled and semi-skilled labour ( Njoya & Seetaram, 2018 ).

2.7. Household income

The distribution of tourism income varies across rural and urban households. Urban households gain higher income from tourism-related industries than rural households ( Eric et al., 2020 ; Kweka, 2004 ; Njoya and Seetaram, 2018 ). Poor (and rural) households receive less income in tourism-related industries and more from other activities such as the primary sector (e.g. agriculture) ( Blake, 2008 ). Thus, some authors consider the redistribution of the tourism sector's benefits to be a measure to counteract poverty and inequality in developing countries ( Alam & Paramati, 2016 ; Gascon, 2015 ; Hall, 2007 ; Scheyvens, 2009 ). Karim and Njoya (2013) find in a CGE study on Kenya that tourism expansion benefits mostly rural households. Kweka (2004) and Njoya and Seetaram (2018) describe rural and farming households as benefitting less than urban households. Both studies find that tourism expansion causes unevenly distributed increases in income among middle- and upper-income households in rural and urban regions. Poverty falls faster in urban than rural areas due to decreased labour demand and earnings in rural households from the agricultural sector.

2.8. Negative impacts on tourism

While most of the reviewed studies have analysed the impacts of policies or scenarios with a positive impact on tourism, until the COVID-19 crisis, only a few studies have analysed scenarios with negative impacts on tourism Damania and Scandizzo (2017) simulated the impacts of reducing the wildlife population, which is the natural capital for safari tourism. They find a negative impact on sectoral growth and an impact from the exchange rate, which spills over to the whole economy. These impacts are especially large among (poor) rural households, resulting from the reduction of foreign exchange flows. Even measures to increase agricultural productivity cannot compensate for losses in tourism and bushmeat hunting.

2.9. Computable general equilibrium studies on tourism and COVID-19

Although the economy-wide impacts of COVID-19 have already been analysed using CGE models, to date, only a few studies have quantitatively evaluated the impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector ( Zenker & Kock, 2020 ), and few used the CGE or dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) framework. Gopalakrishnan, Peters, Vanzetti, and Hamilton (2020) used a CGE model to analyse the short- and medium-term impacts of COVID-19 on the tourism sector in countries with major tourist destinations and those highly dependent on tourism. The authors identified strong linkages and spillover effects between tourism and other sectors. The decline in tourism demand impacts employment and income in many economic sectors. Pham, Dwyer, Su, and Ngo (2021) find comparable significant short-run impacts on job losses in Australia's tourism sector and industries linked to it, ranging from 152,000 jobs (for the tourism sector only) to more than 400,000 (for tourism and tourism linked industries).

Leroy de Morel, Wittwer, Gämperle, and Leung (2020) find for New Zealand that the economic impacts on the tourism sector spill over to the sectors directly linked to tourism industries (e.g. accommodation, food, and transportation services). Travel bans and mobility reductions severely decreased demand for these sectors. At the same time, the imposition of restrictive and isolation measures decreased the output of sectors not directly linked to tourism because of reduced availability of labour and capital (e.g. manufacturing, construction, and other services). Aydin and Ari (2020) show that for Turkey, COVID-19 reduced the output and exports of the tourism and transport sectors, and falling world crude oil prices compensated partially for this fall by reducing energy costs. In addition, in industries not directly linked to the tourism sector, the decreased oil price reduced production costs and increased output. Yang, Zhang, and Chen (2020) evaluated the impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector with health status and health disaster indicators and quantified the impacts of different levels of infection risks on the tourism sector's output and labour productivity. For the longer and greater infection risk of COVID-19, the authors expect significant losses for the tourism sector and the whole economy.

Simulating the impact of COVID-19 on the whole economy, including all sectors, agents and labour market impacts, results in greater effects on GDP and employment than a partial analysis focused only on the tourism sector. A relatively high number of studies have applied CGE models to analyse tourism-related questions for Tanzania (e.g., Adam et al., 2018 ; Damania & Scandizzo, 2017 ; Jensen et al., 2010 ; Kweka, 2004 ; Kweka et al., 2003 ). Njoya (2022) uses a social accounting matrix (SAM) multiplier model to measure the impacts of the COVID-19 tourism crisis in Tanzania, considering the intersectoral and inter-institutional linkages. The SAM multiplier allows for the economy-wide analysis of COVID-19 impacts for the short term. Our study complements the existing academic literature by using a dynamic CGE modelling framework, which provides a quantitative analysis of the COVID-19 impact in Tanzania for the short and the long term.

3. Tourism in Tanzania and COVID-19

The tourism sector in Tanzania has experienced rapid development in steering the Tanzanian economy ( Curry, 1990 ; Wade et al., 2001 ). After independence in 1961, tourism development faced many challenges, namely, poor transportation, accommodation, and information facilities, weak internal tourism education, and poorly funded tourism institutional frameworks ( Wade et al., 2001 ). During the mid-1970s, Tanzania tourism shifted from regional to international tourism involving an expansion of investment, mainly through governmental programmes (e.g., new beaches and holiday projects). During the period 1964–1976, the Tanzanian government contributed 88% of the total investment in the tourism sector. However, government investments were met by accumulating losses and a decrease in revenue caused by declining terms of trade ( Curry, 1990 ).

Recently, the Tanzania tourism sector has grown significantly and has contributed considerably to economic growth in Tanzania ( Kyara, Rahman, & Khanam, 2021 ). Between 2016 and 2019, international tourism arrivals increased by 18.9%, while foreign exchange receipts from international tourism grew by about 25% during the same period. Thus, Tanzania is ranked tenth among 50 African countries in tourism growth. 1 ( WEF, 2019 ). Until April 2020, tourism earnings accounted for more than 24% of the total share of exports, making tourism the second largest foreign exchange earner after agriculture ( NBS, 2019a ). The major source markets for Tanzania's international tourism are the United States of America (13.2%) and the United Kingdom (9.5%).

Tanzania is endowed with a wide variety of landscapes, culture, and wildlife attractions and ranks eighth out of 136 countries globally in natural resource endowments ( WEF, 2017 ). Tanzania's tourist destinations comprise several cultural sites and many natural sites, including six World Heritage sites. Worldwide, Tanzania is the only country that has set aside more than 25% of the total reserve land for wildlife and other resources. 2 Thus, natural amenities and wildlife resources represent a large growth potential for nature-based tourism ( Kweka et al., 2003 ; Sekar, Weiss, & Dobson, 2014 ).

In Tanzania, most tour operators are owned by foreign entrepreneurs. 3 There is evidence that up to 60% of the total profits from the tourism industry are repatriated abroad. Thus, foreign ownership prevents Tanzania from engaging a full array of economic benefits to the booming tourism industry ( Ankomah & Crompton, 1990 ; Kinyondo & Pelizzo, 2015 ). However, Tanzanian tourism contributes significantly through its direct and indirect links to the domestic production of other sectors and economic development. The fact that around 80% of Tanzanian tourism firms are small enterprises makes them vulnerable to financial stress. Since 2000 different global disruptive events (‘black swan’ events) have negatively impacted worldwide international tourism (e.g., the September 11, 2001 attacks, the 2003 SARS epidemic and the 2008–2009 global economic crisis). However, compared to historical black swan events, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the most significant decline in global tourism ( Mwamwaja & Mlozi, 2020 ).

In March 2020, the Tanzanian government adopted key measures to curb the COVID-19 outbreak, such as travel restrictions on international travel or a mandatory 14-day quarantine for international travellers and social distancing. All of these measures affected the tourism sector. These measures were reduced when the government stopped reporting on COVID-19 test results and cases in May 2020. However, Tanzania continued to suffer from a drop in tourist arrivals. Indeed, in 2020, the number of visitors dropped by 60%, while the revenues of public sector tourism institutions decreased by 72% (from 489.4 billion Tanzanian shilling in 2019 to 136.2 billion Tanzanian shilling in 2020) ( World Bank, 2021a ). Unlike many other countries, Tanzania did not implement specific lockdown measures. However, the reduction in tourism travel activities impacted interlinked sectors, particularly air transport, the hotel business, and retail trade. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism in Tanzania is accompanied by various other COVID-19 related impacts, which are not linked to tourism, namely a decrease in oil prices in 2020. Others include a decline in private investment and remittances, a disruption of international trade with China, India, and some European countries (e.g., for agricultural commodities), and a temporary decline in domestic consumption.

4. Methodology

A dynamic CGE model was used to evaluate the short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on the Tanzanian economy. Computable general equilibrium models represent the entire economy, linking different sectors such as tourism to other sectors and institutions such as households. This type of macroeconomic model has been utilised to assess the impacts of pandemics ( Beutels et al., 2009 ; Fofana, Odjo, & Collins, 2015 ; Keogh-Brown, Wren-Lewis, Edmundsa, Beutels, & Smith, 2010 ), and to evaluate the impacts of COVID-19 on the world economy ( Laborde, Martin, & Vos, 2020 ; Maliszewska, Mattoo, & Van Der Mensbrugghe, 2020 ), on a single country ( Chitiga-Mabugu, Henseler, Mabugu, & Maisonnave, 2021a ; Erero & Makananisa, 2020 ; Kinda, Zidouemba, & Ouedraogo, 2020 ), and on households' economic behaviour with gender implications ( Chitiga-Mabugu, Henseler, Mabugu, & Maisonnave, 2021b ; Escalante & Maisonnave, 2021 ; Maisonnave & Cabral, 2021 ).

Fig. 1 presents the flow of the values in a CGE model. In the economy, tourism is linked to other domestic sectors and produces export commodity tourism services for the commodity market. The domestic commodity market provides a supply for the export market, where tourism services are sold as inbound tourism to foreign tourists. The demand for tourism services by foreign tourists determines the price of the service, thus driving the domestic production in the tourism sector. Reduced demand reduces the production of the tourism sector with a corresponding interaction with other sectors via intermediate demand. Reduced production also means a reduced payment for production factor labour to households (i.e., decreased household income). The decrease in exported tourism services and spillover effects on other sectors, income, and consumption results in a decrease in taxes paid as income to the government. Decreased governmental income forces the government to reduce investments in production, which is required to retain economic growth in the long term. Consequently, reduced investment negatively impacts economic growth.

Schematic presentation of the flows in a CGE model. Source: authors' presentation.

We used the dynamic PEP 1-t model developed by Decaluwé, Lemelin, Robichaud, and Maisonnave (2013) and modified it to reflect the Tanzanian economy. The model database is a social accounting matrix (SAM) which represents a snapshot of the Tanzanian economy for 2015. Indeed, this matrix is a consistent framework that retrieves all the flows recorded in the economy for a given year and provides the structure of the economy ( Round, 2003 ). The SAM used in this study was developed by Randriamamonjy and Thurlow (2017) . In line with the matrix, our model has 55 activities and 56 commodities. Of these, 25 are agricultural, 19 belong to the industrial sector, and 11 are in tourism-related sectors such as accommodation and restaurants, retail, and transportation.

We assumed that the production process is nested. At the top level, production is a Leontief-type function between intermediate consumption and value addition. In other words, there is no possibility of substituting value addition with intermediate consumption. At the next level, value addition is a constant elasticity of substitution function between aggregate labour and capital. At the last level, it was assumed that aggregate labour is a constant elasticity of substitution function between the different types of labour, while aggregate capital is a constant elasticity of substitution function between the different types of capital (e.g., land, livestock, machines). For instance, mining capital is used only by mining industries, while crop capital is used only in crop-based agricultural sectors.

Among the different types of labour, workers are disaggregated according to their level of education (no school education, primary education from grades 0 to 4, medium education from grades 5 to 11, and grade 12 or above). If we look closely at the hotel and restaurant sector in Tanzania, we find that 63.5% of its production relies on intermediate consumption, and among the workers hired, more than 90% have primary to secondary education levels (up to grade 11). The information on the factor demand is important for interpreting the results and explaining the links between the tourism sector and the rest of the economy, such as the link to the labour market and other sectors.

Along with the SAM, the model distinguishes three different types of institutions: households, the government, and the rest of the world. Households are disaggregated per quintile of income and whether they are in urban or rural areas. Among households living in rural areas, there is a distinction between farming and non-farming households. All households receive income from labour and capital but in different proportions. For instance, farming households belonging to the lowest quintile of income mainly receive income from unskilled and low-skilled labour, while urban households belonging to the richest quintile of income mainly receive income from mining capital and non-agricultural capital and, to a lesser extent, skilled labour and remittances. Households spend their income on consumption, pay transfers to other institutions and direct taxes, and save the remainder.

The government's income is composed of direct taxes paid by households and firms, indirect taxes, transfers from the rest of the world, and a share of capital income. Indirect taxes account for 46% of the government's income, while direct taxes account for 25%, capital income (mainly non-agricultural capital) accounts for 10%, and transfers from the other institutions for 19%. Government savings are equal to government income less its consumption and transfers paid to other institutions (e.g., social grants, pensions, etc.). Tanzania is linked to the rest of the world via its exports and imports of commodities and through receipts and payment of transfers. Almost 40% of total Tanzanian exports are derived from the service sector, such as the tourism and transport sectors. Agricultural exports account for almost 30% of total exports (e.g., tobacco, coffee, tea, cotton, cashews, and sisal). Given the origin of the commodities, we modelled the links between the rest of the world and Tanzania according to the traditional approach based on the assumption of imperfect substitutability. If Tanzanian producers want to increase their market share in the international market, they need to be more competitive, which is technically translated to set up a finite elasticity for export demand.

Compared to the standard ‘PEP 1-t model’, we changed the assumption of full employment following the modelling of Blanchflower and Oswald (1995) . We assumed a negative slope between wage rates and unemployment rates. In other words, an increase in the unemployment rate leads to a decrease in wage rates. We assumed that labour is mobile across sectors while capital is sector-specific. According to the dynamic assumptions, labour supply increases with an increase in the population rate, while the stock of capital for each sector increases as per the investments made in the sector during the year. The equation that determines the allocation of new investments follows Jung and Thorbecke (2003) . In terms of other closure rules, we took the nominal exchange rate as the numeraire of our model. Following the supposition of small countries, world prices are exogenous; thus we have also presumed that the rest of the world's savings are exogenous, as well as government spending.

5. Scenario design

The COVID-19 pandemic is affecting the Tanzanian economy in many ways through international channels of transmission that are used to inform the design of the scenarios, which are presented in Table 1 . In contrast to other countries, Tanzania did not apply a strict lockdown in 2020. Therefore, COVID-19 shocks are modelled exclusively through international channels. Among them, we identify three channels: remittances, world prices of commodities, and exports. Tanzanian households receive transfers from friends and relatives living and working abroad. Given the economic recession worldwide, this source of income has dwindled. From the BOT (2020) , we can see that it reduced by 29.5% compared to the previous year in 2020. For 2021, we assume that the drop will be 10% and 5% in 2022 for the severe scenario.

Scenarios implemented (in per cent to the business as usual scenario).

Source: Authors' assumptions. Notes: a) The shocks in 2020 are based on observed data and applied to both the mild and severe scenario.

The COVID-19 outbreak has had an impact on world prices on different commodities in 2020, and we expect some impacts in the following years. There was indeed a drop in oil prices due to the drop in international demand, while for gold, wheat, and sugar, we observed a positive impact on world prices. This will impact the Tanzanian economy since Tanzania is a net oil importer and exporter of many minerals. The exports of coal, gold, and manganese account for 30% of total exports. Finally, given the economic situation in trading partner countries, the country faces a decrease in demand for exports. Indeed, Tanzania's main trade partners (India, China, and the United Arab Emirates) face a decrease in their economy, reducing their demand for imports from Tanzania. For instance, India, which accounts for almost 30% of Tanzanian's exports, is expected to face a decrease of 10.3% in 2020 ( IMF, 2020 ), while the second trade partner, the United Arab Emirates, is expected to fall by 6.6% of its GDP ( IMF, 2020 ). The biggest drops in 2020 were observed in the tourism, transportation, and communication sectors.

Indeed, it is already clear that COVID-19 will impact the tourism sector not only in 2020 and 2021 but also in 2022. Thus, long-term effects on tourism, linked sectors, and economies are predicted. Fotiadis, Polyzos, and Huan (2021) find that tourist arrivals could drop to 76.3% and last until at least June 2021. In a study on a group of 20 countries, Kourentzes et al. (2021) expect that under severe scenario assumptions, countries will recover on average to only 34% of their total tourist arrivals in the last quarter of 2021 compared to the same period in 2019. Under a mild scenario assumption, the average recovery was 80%. Polyzos, Samitas, & Spyridou (2021) find that the recovery of Chinese tourists arriving at the pre-crisis level in the USA and Australia could take between 6 and 12 months.

More than 40% of international tourism experts expect the global tourism sector to recover to its 2019 level in 2024 or later, with only 15% of experts anticipating a recovery by 2022 (UNWTO Panel of Tourism Experts, January 2021). Moreover, it is likely that COVID-19 will modify the behaviours of tourists who may prefer to travel to familiar and trusted places. For instance, for China, Huang, Shao, Zeng, Liu, and Li (2021) found that tourists avoided travelling to places with more confirmed cases of COVID-19 compared to their places of origin. This argument is relevant in Tanzania's case. Indeed, by refusing in 2020 to acknowledge the existence of the coronavirus in Tanzania, the previous government only fell behind in providing care and access to vaccination. It is possible that tourists will be afraid to return to Tanzania if only a small proportion of the population is vaccinated.

It is quite challenging to estimate a “back to normal” situation in the tourist arrivals, as most countries are experiencing a third or fourth wave of COVID-19. Therefore, we designed two scenarios: a mild scenario and a severe scenario. These two scenarios differ in the magnitude and duration of the shocks from 2021 onwards. However, for both scenarios, in 2020, the same magnitude is applied. Since based on observed data and we label the year 2020 as a “historical” simulation year. In the mild scenario, we estimate a return to normal in 2022, whereas in the severe scenario, the return to normal will be in 2023. The model runs from 2015 (year of the SAM), a so-called ‘business as usual’ scenario until 2030, without any shocks assuming a regular path of economic growth. The economic shocks caused by COVID-19 are applied in 2020 and 2021 for the mild scenario and in 2020, 2021, and 2022 for the severe scenario. When analysing the results, we compared the values obtained with the mild and severe scenarios to those of the “business as usual” scenario. We present the values obtained for 2020, 2021, and 2030.

For 2020, we computed the magnitudes of the shocks using the BOT (2020) . For the scenario year 2020, information is available that remittances (inflows excluding those going to the government) dropped by almost 30% compared to the business as usual scenario. It should be noted that for the scenario years 2021 and 2022, the simulated decreases in remittances are not based on official sources but on the authors' assumptions. Given the ongoing pandemic for 2021 and the coming years, official estimates of changes could not be researched. We assume in the mild scenario that the Tanzanian economy would continue to be affected but not as severely as 2020 and return to its business as usual situation in 2022. For the severe scenario, in 2021, the economy will still be heavily affected, and for 2022, we envisage that only a couple of sectors (mainly tourism and transport) would remain stricken. We assume that discovering new COVID-19 variants (such as Omicron) leads to preventive reactions from different countries that directly affect the tourism and transport sectors. The economy would return to its business as usual level in 2023.

6.1. The macroeconomic impacts

The COVID-19 related shocks are quite harsh in the Tanzanian economy. Indeed, as mentioned above, the effects on Tanzania are via a number of channels (e.g. drop in tourists, decrease in exports, differing world prices, and decreased remittances). In 2020, Tanzania experienced a decrease in GDP of 1.88%. In 2021, in the mild scenario, the decline in GDP is slightly lower than in 2020, while under the severe scenario, Tanzania suffers a higher loss. In both scenarios, in the long run, GDP would still be lower than what it would have been without the pandemic, with a drop in GDP by 0.38% in the mild scenario compared to 0.54% in the severe scenario (see Table 2 ). The negative impact on economic growth caused by a contraction of the tourism sector, as well as trade shocks, is in line with studies describing the positive impact of tourism expansion (e.g., Kweka, 2004 ; Njoya & Seetaram, 2018 ). Since Tanzania's tourism sector was expanding until 2019 ( Kyara et al., 2021 ; WEF, 2019 ), the negative shock caused by COVID-19 has created an inverted (negative) impact on growth. The macroeconomic impacts simulated for Tanzania are comparable to the results of other studies on COVID-19 impact on tourism (e.g. Leroy de Morel et al., 2020 ; Pham et al., 2021 ).

Macroeconomic impacts, selected indicators (in per cent change to the business as usual scenario).

Source: Authors' simulation results. Notes: a) The shocks in 2020 are based on observed data and applied to both the mild and severe scenario.

The drop in tourism demand, combined with the linked drop in transportation and communication services, forces sectors to reduce production and lay off workers. These sectors reduce their intermediate demand, which in turn negatively impacts other sectors. These results are consistent with the strong backward linkages described by Adam et al. (2018) and Kweka (2004) . In contrast to these studies, Tanzanian tourism suffers a contraction, thus creating a negative impact on the growth of the strongly linked sectors. Consequently, we observe a drop in total labour demand from tourism and linked sectors by more than 3.3% in 2021. This drop in labour demand impacts households by reducing their income and then their consumption, ceteris paribus. Households' real consumption decreases by 5.1% in 2020, and in the long run, for both scenarios, it is still below the level of the business as usual scenario.

6.2. Impacts on the tourism sector and other sectors

In 2020, given the massive reduction in travellers, the production of the tourism sector is declining by more than 13% (see Table 3 ). The sector is laying off workers and is no longer attractive for private investment. The drop in production continues throughout the period under mild and severe scenarios. In the long run, production is still slightly below what it would have been without the pandemic. We can point out that the sector hires again and attracts more investment at the end of the period in 2030. However, the investments in the current period will be effective as capital in the next period (i.e., after 2030). To reach the level of services, as would have been the case without COVID-19, policy measures (e.g., more investments) will be needed to stimulate the expansion of the tourism sector (e.g. more tourism activities to Tanzania) and more investments. Pro-tourism measures would indirectly support the recovery of sectors linked to tourism. The strong linkages between tourism and other sectors ( Eric et al., 2020 ; Mayer & Vogt, 2016 ; Njoya & Nikitas, 2020 ; Suau-Sanchez et al., 2020) cause a decrease in the production of the linked sectors (see Table 4 ).

Impacts on labour demand, investments, and production in the tourism sector (in per cent change).

Source: Authors' simulations results. Notes: a) The shocks in 2020 are based on observed data and applied to both the mild and severe scenario.

Impacts on labour demand and production of the tourism sector and linked sectors (in per cent change).

For instance, the transport sector faces a drop of 11.7% of its production in 2020, and the decline continues even after the economy goes to its business as usual level. Note that under the severe scenario, the sector's production is almost as affected as in 2020, resulting in layoffs in the sector. These reduced labour demands from the transportation sector are in line with the inverted observations of Njoya and Seetaram's (2018) study, which describes the significant positive impact on tourism caused by expanding the transportation sector. For the construction sector, the drop in production is also linked to the drop in total investment ( Table 2 ), thereby affecting investment goods such as construction commodities.

6.3. Impacts on Tanzanian households