Example sentences emotional journey

Definition of 'journey' journey.

Definition of 'emotional' emotional

COBUILD Collocations emotional journey

Browse alphabetically emotional journey.

- emotional investment

- emotional involvement

- emotional issue

- emotional journey

- emotional labour

- emotional literacy

- emotional manipulation

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'E'

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Organizational Transformation Is an Emotional Journey

- Andrew White,

- Michael Smets,

- Adam Canwell

Seven strategies to help leaders navigate the process.

It’s not news that organizational transformations are prone to failure. To understand the skills, mindsets, and capabilities behind successful transformations in today’s dynamic environment, EY and Oxford University formed a research collaboration to investigate what it takes to lead a successful transformation. One of the authors’ most important findings is that, in order for transformation to be successful, leaders must approach it in ways designed to mitigate emotional harm to — and drive emotional commitment from — employees. The workforce bears the brunt of failed transformations, and the emotional damage can be substantial as employees lose confidence in leaders and become skeptical of further attempts at transformation. Drawn from their research, the authors present seven ways for leaders to set their transformations up for success by prioritizing their employees’— and their own — emotions.

The road is littered with failed transformation programs that were set up in the traditional way: Leaders define objectives, design a project plan, agree on KPIs, and recruit the right people. As many executives, academics, and consultants can relate to, the rate of failure in transformations is still far too high, and one that organizations can ill afford in these disruptive times.

- Andrew White is a senior fellow in management practice at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, where he directs the advanced management and leadership program and conducts research into leadership and transformation. He is also a coach for CEOs and their senior teams.

- Michael Smets is a professor of management at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. His work focuses on leadership, transformation, and institutional change.

- AC Adam Canwell is head of EY’s global leadership consulting practice. Adam has published extensively on leadership and strategic change. Adam has sold and delivered transformation programs across multiple industries in both the UK and Australia, working with FTSE 100 (or their equivalent) organizations .

Partner Center

- Self-Growth Journey

- Free Newsletter

Emotional Self-Healing: How to Start Your Powerful Journey Today

Personal Development

E ach person is different when it comes to emotional pain and trauma. Some elements, such as death, affect all of us similarly, but even within that context, our reactions and the way we feel and deal with them are different. Self-healing is a process through which you acknowledge the emotional pain and trauma in your life and figure out a way to stop it from holding you back. Unlike a band-aid that can stop the bleeding and eventually the scar will go away, emotional pain and trauma is a long and slow process, and its appropriate “band-aid” doesn’t exist in a one-size-fits-all type of box. This article explores the concept of self-healing and proposes a few ways in which you can start your self-healing journey today.

What Is Emotional Pain

In a 2011 article published in the Journal of Loss and Trauma , researchers Esther Meerwijk and Sandra Weiss asserted that “a generally accepted understanding and clear definition of what is constituted by psychological pain do not exist.”

It’s an interesting study that explains the difficulty of defining emotional pain in a cohesive, easy-to-understand manner.

In the end, the authors do provide their view on a unified definition that states that “[…] psychological pain is being defined as a lasting, unsustainable, and unpleasant feeling resulting from the negative appraisal of an inability or deficiency of the self.”

Although it starts to sound a little easier to understand, it’s still far from a set of checkboxes that would answer the question, am I in emotional pain or not.

Since defining emotional pain is complex, dealing with emotional pain and trauma is equally challenging. You can’t truly solve a puzzle if you cannot describe the puzzle and how it works. Emotional pain is one of those puzzles because when you feel it, you know it’s there. But if someone asks you to describe it, you are lost for words.

In an article on emotional pain , Dr. Steven Stosny, Ph.D., explains that when you dwell on the causes of emotional pain, you will most likely exacerbate it rather than alleviate it.

It’s normal to think that if you were to find the cause of your emotional pain and thus assign the blame to that cause, the emotional pain would go away. However, self-healing doesn’t work that way. The more you attempt to cast the fault, the more you must shine a light on the pain and make it bigger. That’s the opposite of a self-healing journey and will lead to a life of resentment while the trauma persists.

How Emotional Pain Affects Us

When you suffer from emotional trauma, there’s little outside evidence about what is happening on the inside. That’s why often, people around you might brush off your emotional pain, which will make you feel even worse.

The truth is that emotional pain is not only just as real as physical pain, but many times it’s much more powerful and much more damaging.

The difference to physical pain is the clear answer to where and why. If your shoulder hurts, you get an X-ray. If the X-Ray reveals a tear, the doctor will give you an injection and immobilize your arm for a while. While both of those things will hurt, there is a plan in place to eventually remove the pain and make it all better.

With emotional pain, the cause is often unclear. With the unclear cause, the path to “all better” is not only foggy; it doesn’t even exist.

That lack of direction as to how to deal with emotional pain will only make the pain more prevalent and add a layer of helplessness to it.

When those kinds of feelings inhabit you, the mental pain will often translate into physical pain. Dizziness, headache, upset stomach, nausea, stiff muscles—those are just a few types of physical psychosomatic reactions in which emotional pain manifests in your body.

On top of that, emotional pain changes your behavior and attitude. You may find yourself angry , overeating, over-drinking, isolating or even self-harming.

This cocktail of feelings and reactions turns into an emotional tornado that keeps spinning, and spinning, and spinning. So, the question becomes, how can you get out of it?

What is Self Healing?

Self-healing is a process by which you work toward recovering from emotional pain and trauma. Although the “self” in the name is a driving force, that doesn’t mean that you must do it alone.

The self implies strong self-motivation and self-discipline , but the self-healing journey is often best accomplished alongside a supportive group. That group can be your family, friends, or professional help.

One crucial aspect of this journey is self-awareness . As in the example above, if you were not to feel the pain in your shoulder, you’d never get to the doctor, and your shoulder might remain damaged for good. Similarly, when it comes to emotional pain and suffering, you must at least be aware that it exists before you can do something about it.

Unluckily, that’s a tricky thing to do. Luckily, though, there’s a process in place that can get you there.

6 Stages of Self-Healing

As the complexity of emotional pain and trauma are apparent by now, self-healing is not straightforward. Although putting down six stages sounds simple enough, the reality is a lot more convoluted.

The stages are not an exact science; they’re not a computer program that you can run linearly for a determinate time. Instead, these stages happen differently for different people. They can last longer or shorter; they might go in this order or out of order.

The goal of the stages is to bring forward the awareness of a “possible” road to self-healing. Each person will create their own path using their understanding of where they are and where they want to be. It’s like a map, but everyone will approach it in their own way.

The idea here is to begin the self-healing process, which will scar the emotional pain and eventually remove the scar tissue. Once that has been at least partially removed, there will be new space for personal change and transformation, no longer shadowed by the effects of the trauma. The ultimate goal for that is achieving deep inner peace.

When grief sets in and transforms into long-lasting emotional pain resulting from trauma, your first reaction is to deny it. That is not uncommon, and it applies to almost everything that gives us discomfort. The first reaction is to pretend it’s not there in hopes that it might, in fact, not be real and it will go away.

Some people never leave this stage and spend their entire lives stuck in denial. They might deny that an abusive relationship exists because there can’t be any pain if it doesn’t.

Self-awareness and getting a sense of self-esteem is a way for people to start getting out of denial. By honestly examining what you fear might happen should you stop denying, you begin to open the door for leaving this stage.

When you no longer deny reality and understand that something is genuinely happening to you, the next thing that usually follows is anger. “Why me?” “Why is this happening?” “How can they let this happen to me?”

Those are questions that you ask in anger because you are upset at your suffering. Anger can manifest outwardly toward others or inwardly toward yourself. You might become vicious with other people, or you might self-harm.

Whereas anger is an essential step in the self-healing journey, spending too much time in anger might result in long-term resentment. The critical part is observing the anger, expressing it healthily, but being prepared to let go of it.

The next usual stage is bargaining, which is your way of trying to find a quick fix. It’s an “if only” kind of solution.

“If I do this, maybe he won’t do that, and so I won’t feel this way anymore.”

“If you come to counseling with me, I won’t file for divorce.”

“I only need to be lucky this one time, and things will turn around.”

“Please, God, if you can, just give her one more month.”

Bargaining is an attempt to regain control that has been lost. We often feel that nothing comes for free, so if we offer something or invoke something, we might get back an alleviation of pain.

You might find yourself bargaining for love, time with a loved one, financial security, or so many other things. This transitory natural stage provides a temporary escape out of denial and anger while the person in pain can adjust to the reality that is starting to set in.

Depression sounds like it could be one of the effects of emotional pain. To some extent, that’s true, but in the context of your self-healing journey, depression signals the beginning of acceptance. On the cusp of acceptance, there’s still resistance; you’re not yet entirely over the hurdle, but you’re close.

During this time, some of the effects of emotional pain exacerbate. You may feel intense sadness, difficulty sleeping, loss of motivation, inability to focus, and a general feeling of loss of self-worth.

Although the depression stage sometimes feels like it will last forever and become the ultimate end-point to that journey, it is also a transitory yet necessary phase.

At this stage, it’s essential to have a trusted group with whom you can feel comfortable expressing your feelings and discussing them without judgment.

It’s not easy to predict how long the depression stage will last, but by practicing daily feeling and expressing your emotions, you can ensure a smoother transition out of it.

The acceptance stage marks the point when you finally understand and accept the reality of the pain or trauma, and that reality cannot change. It means that you have been able to detach yourself from the claws of the past and everything that you regret about it. Similarly, the future doesn’t scare you anymore, and you are ready to move forward.

Note that acceptance doesn’t mean that you are “okay” with the loss, although its name might suggest it. You may never be “okay” with your mother not being alive or your spouse cheating on you. What matters is that you accept those realities for what they are, and you can move on without being paralyzed by their mere existence.

Acceptance is your ability to learn how to live with the present and how the present looks like. It is a process, though, and not the means to an end.

Forgiveness

Last but not least is forgiveness. Although acceptance gives you the freedom you need to unclench yourself from the claws of emotional pain and gain the wings you need to fly, resentment toward the cause of the pain might not disappear completely.

Think about a spouse who abused you or a man who hurt someone you love. Although you have accepted the reality, you may still hold a grudge toward those people.

When you truly forgive, you finally free yourself. That freedom is a bonus on your self-healing journey because it genuinely seals the grip that the person or event has on you.

Note that forgiveness cannot happen until you remove yourself from the cause of emotional pain and you go through the different stages of grief.

In other words, don’t mistake forgiveness for bargaining.

“I’ll forgive him and give him another chance. He promised it wouldn’t happen.” That’s not true forgiveness; it’s just another way of negotiating your emotions and giving control away.

Begin Your Self-Healing Journey

Emotional pain is one of the most difficult ailments that can affect you, and it’s extremely difficult to defeat. That’s mainly because ordinarily, you might not even be aware that it happened. You feel the effects but understand none of the causes.

That not only creates frustration and additional anxiety, it also blocks your way to breaking its chains.

Therefore, understanding the self-healing journey and going through those stages is critical for removing yourself from that emotional pain and moving on with your life.

It’s a tough and challenging road, but one that, once taken, will drive you to freedom .

Other Resources on Self-Healing

- 7 Ways to Heal Your Body by Using the Power of Your Mind, Backed by Science

- 10 Tips for Emotional Healing

- How To Emotionally Heal Yourself?

- Healing: 5 Steps To Transforming Emotional Pain

Now, before you go, I have…

3 Questions For You

- Are you currently living with emotional pain or trauma?

- Do you recognize yourself in any of the six stages of dealing with emotional pain?

- If you’ve defeated emotional pain before, how do you feel now?

Please share your answers in the comments below. Sharing knowledge helps us all improve and get better!

Hi there! I’m Iulian, and I want to thank you for reading my article. There’s a lot more if you stick around. I write about personal development, productivity, fiction writing, and more. Also, I’ve created Self-Growth Journey , a free program that helps you get unstuck and create the beautiful life you deserve. Enjoy!

Related posts:

emotions, happiness, self-help

Lilian, I am ever so grateful this is amazing I am going to put you down as my nb1 on my social media’s you really put my mind at ease. THANK YOU THANK YOU THANK YOU,, I wish you nothing but the best in life ??

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

17 Transformative Techniques to Become More Emotionally Available and Open

Does emotional availability feel like a distant concept out of your reach?

You're not alone.

Navigating our feelings and expressing them openly can be daunting.

Yet, it is essential for forging deeper relationships and enjoying emotional health.

Let’s unveil 17 practical strategies to enhance your emotional receptiveness and tear down the walls of fear and hesitation.

We’ll explore the profound world of emotional authenticity, vulnerability, and connection, one step at a time.

Unraveling Emotional Availability: The Art of Being Present and Engaged

1. embrace self-acceptance, 2. practice mindfulness, 3. foster self-compassion, 4. develop emotional literacy, 5. strengthen your emotional resilience, 6. practice active listening, 7. cultivate empathy, 8. prioritize emotional self-care, 9. develop healthy coping mechanisms, 10. embrace vulnerability, 11. engage in emotional detox, 12. foster emotional agility, 13. seek professional help if needed, 14. cultivate patience, 15. practice regular reflection, 16. encourage emotional conversations, 17. build trust in relationships, final thoughts.

What does it mean to be emotionally available?

At its core, emotional availability refers to the capacity to share your feelings openly, listen actively, and respond empathetically to another person's emotional experiences.

It's about letting your guard down and allowing yourself to experience a full range of emotions without pushing them aside or burying them under layers of denial or defense mechanisms.

The hallmarks of emotional availability encompass a broad spectrum of behaviors and attitudes:

- Active Listening: This means truly hearing and understanding the emotions of others, not merely waiting for your turn to speak.

- Vulnerability: It involves the courage to convey your feelings and needs without fear of judgment or rejection.

- Empathy: This is the ability to feel with others, understanding their emotions on a deeply personal level.

- Responsiveness: Responding appropriately to others' emotions, providing comfort, and validating their experiences.

- Self-Awareness: It's about recognizing and understanding your own emotions, thus enhancing your emotional intelligence.

In essence, being emotionally available means being fully present — with yourself and others.

It involves creating a safe emotional space where authentic communication can flourish, fostering deeper and more meaningful relationships.

How to Be Emotionally Available With These 17 Actions

Let's dive into the heart of the matter—your journey toward being a more vulnerable person.

These transformative actions will guide you towards a more empathetic, responsive, and authentic emotional life, empowering you to foster stronger, healthier connections.

Start with acknowledging and accepting your feelings, for they make you human. This isn't about always being pleased with your actions or emotions but about recognizing that they're a part of you.

Self-acceptance is the cornerstone of emotional availability because it removes the fear of confronting and communicating your feelings. By accepting yourself fully, you lay the groundwork for openness with others, fostering a sense of inner peace that helps create secure emotional spaces.

Incorporating mindfulness into your daily routine can ground you in the present moment and heighten your awareness of your feelings as they arise. This enhanced self-awareness can prevent emotional build-up and facilitate better communication.

Instead of reacting impulsively to emotions, mindfulness teaches you to respond thoughtfully, bringing clarity and balance to your emotional life. By consistently practicing mindfulness, you nurture your ability to articulate and respond to emotions clearly and compassionately.

Embracing self-compassion means treating yourself with kindness and understanding when confronting personal failings or mistakes. It can help eliminate the self-judgment that often stifles emotional expression.

Acknowledge that everyone has imperfections and experiences challenging emotions. By cultivating self-compassion, you foster an environment where emotions can be freely acknowledged, accepted, and articulated, paving the way for increased emotional availability.

Being emotionally literate involves understanding and being able to articulate your own emotions. This skill makes it easier to recognize and manage your emotional responses. Start by naming your feelings and understanding what triggers them.

Keep a journal to track your emotional journey, which can provide valuable insights into your emotional patterns. With increased emotional literacy, you gain control over your emotional responses, making it easier to communicate your emotions to others and build deeper connections.

Building emotional resilience involves enhancing your ability to bounce back from emotional hardships. It teaches you to handle stress and adversity more effectively, preventing emotional shutdown in challenging situations.

Resilience doesn't mean ignoring negative emotions; instead, it's about accepting them and moving forward . Through activities like meditation, exercise, and seeking social support, you can fortify your emotional resilience, promoting transparency and willingness to engage emotionally with others.

Active listening is a crucial part of being emotionally available. It involves not just hearing but truly understanding someone else's feelings . When you listen actively, you're fully present and focused on the other person, devoid of any preconceived notions or judgments.

This active engagement creates a healthy and receptive environment for them to express their emotions and signals their feelings are valued and understood. Cultivating this skill can foster trust and respect and deepen your emotional bonds.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. By putting yourself in someone else's shoes, you gain a deeper understanding of their experiences. It's more than mere sympathy—it involves connecting with others on a deeper emotional level.

Cultivating empathy requires practice, tolerance, and open-mindedness, but the rewards are invaluable, leading to enriched emotional interactions and stronger, more genuine connections.

Your emotional health is paramount. By prioritizing emotional self-care, you ensure that your emotional needs are met, enabling you to be more present and available for others. This can involve a range of activities, from pursuing hobbies you love to setting healthy boundaries to seeking professional help if needed.

By caring for your emotional health, you equip yourself with the strength and capacity to be more emotionally available to others.

Life is filled with ups and downs. Developing healthy coping mechanisms helps you navigate through these fluctuations without repressing or ignoring your feelings. Techniques such as deep breathing, meditation, or engaging in physical activity can prove helpful.

When you manage stress and difficult emotions effectively, you maintain your emotional equilibrium, making you more available to connect with others.

Vulnerability involves the courage to express your feelings and needs without fear of judgment or rejection. It may feel risky, but it's a fundamental aspect of this mindset. Embracing vulnerability requires a shift in perspective—seeing it not as a weakness but as a strength that enhances authenticity.

Learn to be more real and vulnerable, and you create deeper, more meaningful relationships, creating an environment of mutual trust and honesty that forms the backbone of emotional availability.

An emotional detox involves taking time to clear out unwanted or negative emotions that might be hindering your emotional openness. It's about acknowledging, processing, and letting go of emotional baggage that weighs you down.

This might involve journaling, mindfulness exercises, therapy, or other reflective activities. You will cleanse your emotional palette, making room for positive and constructive feelings and enhancing your capacity for emotional connection.

Emotional agility is the ability to navigate life's emotional twists and turns with flexibility and resilience. It means being able to experience and accept all of your emotions, whether positive or negative, without getting stuck or overwhelmed.

Developing emotional agility can involve practicing mindfulness, pursuing personal growth, and reframing your perspective on challenges. When you cultivate this skill, you become more adaptable and transparent in your emotional interactions.

Sometimes, the road to this kind of vulnerability requires professional guidance. Therapists and counselors are equipped with the tools to help you explore your emotions and overcome potential roadblocks.

They can provide you with strategies to manage stress, build resilience, and improve emotional literacy. Don't shy away from seeking help—it's a sign of strength and a step towards becoming more emotionally available.

Becoming emotionally available is a journey, not a destination. It takes time to unlearn old habits and cultivate new ones. Patience is key in this process, and it's essential to give yourself grace as you navigate through this transformation.

Remember, small, consistent steps can lead to substantial changes over time. Celebrate your progress, be gentle with your setbacks, and don't rush the process – patience will make your journey toward emotional availability smoother and more fulfilling.

Taking time each day to reflect on your emotions and your responses to them can be a powerful tool in your journey toward being more unguarded. This regular introspection can help you understand your emotional patterns, identify areas where you can improve, and celebrate your progress.

It can be as simple as meditating at the end of the day. Incorporating reflection into your routine helps you enhance your emotional self-awareness, a fundamental step towards increasing emotional availability.

Creating a safe environment for emotional conversations is crucial in enhancing your emotional responsiveness. Encourage these discussions in your relationships, showing you're willingness to explore feelings together.

This promotes mutual understanding and emotional connection. You not only become more emotionally available yourself but also encourage the same in others.

Trust is the bedrock of emotional availability. It provides a safe environment for you to express your emotions without fear of judgment or criticism. Building trust in your relationships involves being reliable, maintaining confidentiality, showing empathy, and being honest.

The more trust you cultivate, the more emotionally available you can become, paving the way for healthier and deeper emotional connections.

More Related Articles

Cut the Chatter With These 21 Practical Tips To Stop Talking So Much

9 Types Of Intimacy In A Relationship Every Couple Should Understand

11 Top Signs Of An Emotionally Stunted Man

Why Is It Hard for Me to Be Emotionally Available?

The journey toward this openness is not always smooth sailing. You may encounter hurdles that make it difficult to reveal or receive emotions freely. Understanding these challenges is the first step to overcoming them.

Several factors could contribute to difficulties in being closed off:

- Past Trauma: Previous emotional wounds or traumatic experiences can create a fear of vulnerability, causing one to build emotional walls as a defense mechanism.

- Lack of Role Models: Not having had examples of relational openness during your formative years can make it challenging to understand and practice it in your own life.

- Fear of Rejection: The fear of being rejected or misunderstood can often deter one from sharing their emotions openly.

- Poor Self-Esteem: People with low self-esteem may struggle with being emotionally expressive because they may not value their own feelings or believe they're worthy of emotional connection.

- Cultural or Societal Expectations: Certain cultural or societal norms can stifle emotional realness, especially in those who've been taught to suppress their feelings.

Navigating these barriers can seem overwhelming, but it's important to remember that each step you take toward deeper connections, no matter how small, is a step in the right direction.

Overcoming these obstacles often involves self-reflection, patience, and sometimes professional help. Rest assured, the rewards of becoming more emotionally available—a more fulfilling relationship with yourself and others—are well worth the effort.

Embarking on the path of emotional availability is akin to a journey of self-discovery. It unveils the layers of your emotional being, fosters empathy, and strengthens your connections. Embrace this transformative process, for it's an investment in your emotional health, well-being, and the quality of your relationships.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home QuestionPro QuestionPro Products

Emotional Journey Mapping: What it is + How to Create it?

A typical journey map is a visual representation of a person’s steps to achieve a goal, but an emotional journey mapping adds a new twist to this age-old technique.

Emotions are an excellent way to determine whether your customer is in a good, bad, or neutral mood while completing a purchase. This game-changer will teach you how to improve a journey map.

In this blog, we will learn what emotional journey mapping is and how to create one for your business. Let’s get started.

What is emotional journey mapping?

Emotional journey mapping is a way to understand and track how customers or users feel as they interact with a product, service, or brand.

The process involves finding the key touchpoints or interactions that the customer or user has with the product, service, or brand and figuring out the emotions that the customer or user may feel at each touchpoint.

The data is represented in a timeline or flowchart to discover customer experience regions that may create negative emotions and those that may be modified to increase positive feelings.

It can help businesses determine how to improve their customers’ experiences by understanding their emotional needs and want.

You may also check out this guide to learn how to build your own Customer Journey Map .

Importance of emotional journey mapping

Emotional journey mapping helps businesses to understand customers’ emotions and experiences throughout their interactions with the company. Some key importance is given below:

- Emotional journey mapping helps companies identify customer frustration and uncertainty. This data can then be used to improve the customer experience.

- Using emotional journey maps, companies can better understand the unique emotional needs of various customer segments. It can be used to customize experiences for different customer segments.

- Companies can develop stronger, more meaningful relationships by understanding customers’ emotions and experiences throughout their journey. Here, we will discuss some key importance of the emotional journey map below:

How to create emotional journey mapping?

Emotional journey maps show customer journeys. Here, the focus is on user satisfaction rather than product engagement. Understanding a user’s feelings helps create effective improvements. To create an emotional journey map, follow these steps:

- Create user persona

Create a user persona to begin creating the map. Consider your users and create a persona for each segment. Not all of your customers will have the same requirements (or ways of meeting those needs).

It is frequently preceded by user research. These personas can be developed using user interviews, focus group discussions, surveys, and prior user feedback.

- Create a scenario

We need a scenario that addresses users’ expectations and requirements to achieve their goal of creating emotional journey mapping. The scenario could be about interactions with people, events, or objects.

- Goals and tasks

The next step is to identify the goals and the tasks. A task is an action that the user needs to do in a certain amount of time or in a certain way. Each journey has a different set of goals and tasks. They provide structure for the rest of the customer journey map.

Example: A customer journey is a series of goals and tasks. Let’s say a family wants to go on vacation from place Y to place Z.

- Goal: The goal is to prepare for the trip from place Y to place Z.

Solution: supply a customer with a map of the place, hotels, restaurants, stopovers, etc.

- Task: The task is to rent transport to travel from place Y to place Z.

Solution : provide a quick and easy way to rent transport.

- Surveys or Interviews to gain understanding and real data

In this step, you need to ask questions to better understand your customers’ world, background, and experiences with your company. Surveys or interviews are the best options for knowing your customers’ thoughts.

You can ask customers about their feelings related to their experience to learn how and why they felt a specific way at each touchpoint, stage, and interaction during their journey with you.

Actively listen and analyze how they communicate and how they convey their experience.

- Interpreting data

You can organize all of your customer data, such as conversations, experiences, emotions, thoughts, and actions, based on how similar, important, and relevant they are.

Create a team to identify trends in the data.

Learn more about why understanding your Customer Journey transforms your CX program.

Sort conversations by where customers are in their journey and what they are thinking and experiencing. After that, customers’ emotions can be identified.

- Line up data-based evaluation points

In this step, draw a line graph to show how a customer’s feelings changed at each touchpoint and interaction. Do this for each different persona you create. The customer’s highs and lows are displayed using emoticons and an emotion graph throughout the entire journey, from start to finish.

- Analyze and improve the journey

Look at both the good and bad parts of the journey to learn more and understand it. Highlight points and possibilities to improve the emotional journey mapping.

- Implementation

After analyzing your emotional journey map, it’s time to implement it into your business. Make sure you implement your journey map properly to get the most advantage.

- Review and Monitor emotional journey mapping

It’s time to monitor your emotional journey map after the implementation step. You have to monitor how your customers respond to your journey map. Observe all the small or big things on your emotional journey map and take action according to them.

How can QuestionPro Cx enhance emotional journey mapping?

QuestionPro is survey software that allows users to create and distribute surveys to collect data about customer experiences and perceptions. QuestionPro CX can assist with emotional journey mapping by allowing you to create surveys that specifically target the various stages of a customer’s emotional journey.

Surveys are used to collect data on a customer’s feelings and perceptions at various stages of the journey, such as the awareness, consideration, and post-purchase stages. This data can then be used to map the customer’s emotional journey and identify areas for improvement.

QuestionPro CX also offers tools for analyzing and visualizing survey data, which can be used to gain insights and make decisions based on the customer’s emotional journey.

The goal of emotional journey mapping is to gain insight into how customers feel at various stages of their journey and identify areas for improvement to improve their overall experience.

It is a valuable method for understanding and improving the customer experience, and it can assist businesses in developing strong customer relationships.

Ow, it’s time to create your emotional journey mapping for your business. If you need any help regarding journey mapping, Contact QuestionPro!

QuestionPro is survey software that can be used to map emotional journeys. Users can use the platform to create and distribute surveys that target specific stages of the customer’s emotional journey.

QuestionPro can be a valuable tool for businesses looking to map their customers’ emotional journeys and improve their customer experience.

Try out QuestionPro today!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Unlocking Creativity With 10 Top Idea Management Software

Mar 23, 2024

20 Best Website Optimization Tools to Improve Your Website

Mar 22, 2024

15 Best Digital Customer Experience Software of 2024

15 Best Product Experience Software of 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Catharsis in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

i love images / Getty Images

- Catharsis Definition

Therapeutic Uses of Catharsis

Catharsis in everyday language, examples of catharsis.

Catharsis is a powerful emotional release that, when successful, is accompanied by cognitive insight and positive change. According to psychoanalytic theory , this emotional release is linked to a need to relieve unconscious conflicts. For example, experiencing stress over a work-related situation may cause feelings of frustration and tension.

Stress , anxiety, fear, anger, and trauma can cause intense and difficult feelings to build over time. At a certain point, it feels as if there is so much emotion and turmoil that it becomes overwhelming. People may even feel as if they are going to "explode" unless they find a way to release this pent-up emotion.

Rather than venting these feelings inappropriately, the individual may instead release these feelings in another way, such as through physical activity or another stress-relieving activity.

The Meaning of Catharsis

The term itself comes from the Greek katharsis meaning "purification" or "cleansing." The term is used in therapy as well as in literature. The hero of a novel might experience an emotional catharsis that leads to some sort of restoration or renewal. The purpose of catharsis is to bring about some form of positive change in the individual's life.

Catharsis involves both a powerful emotional component in which strong feelings are felt and expressed, as well as a cognitive component in which the individual gains new insights.

The term has been in use since the time of the Ancient Greeks, but it was Sigmund Freud's colleague Josef Breuer who was the first to use the term to describe a therapeutic technique. Breuer developed what he referred to as a "cathartic" treatment for hysteria .

His treatment involved having patients recall traumatic experiences while under hypnosis . By consciously expressing emotions that had been long repressed, Breuer found that his patients experienced relief from their symptoms.

Freud also believed that catharsis could play an important role in relieving symptoms of distress.

According to Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, the human mind is composed of three key elements: the conscious, the preconscious, and the unconscious . The conscious mind contains all of the things we are aware of.

The preconscious contains things that we might not be immediately aware of but that we can draw into awareness with some effort or prompting. Finally, the unconscious mind is the part of the mind containing the huge reservoir of thoughts, feelings, and memories that are outside of awareness.

The unconscious mind played a critical role in Freud’s theory . While the contents of the unconscious were out of awareness, he still believed that they continued to exert an influence on behavior and functioning. Freud believed that people could achieve catharsis by bringing these unconscious feelings and memories to light. This process involved using psychotherapeutic tools such as dream interpretation and free association.

In their book Studies on Hysteria , Freud and Breuer defined catharsis as "the process of reducing or eliminating a complex by recalling it to conscious awareness and allowing it to be expressed." Catharsis still plays a role today in Freudian psychoanalysis.

The term catharsis has also found a place in everyday language, often used to describe moments of insight or the experience of finding closure. An individual going through a divorce might describe experiencing a cathartic moment that helps bring them a sense of peace and helps that person move past the bad relationship.

People also describe experiencing catharsis after experiencing some sort of traumatic or stressful event such as a health crisis, job loss, accident, or the death of a loved one. While used somewhat differently than it is traditionally employed in psychoanalysis, the term is still often used to describe an emotional moment that leads to positive change in the person’s life.

Catharsis can take place during the course of therapy, but it can also occur during other moments as well. Some examples of how catharsis might take place include:

- Talking with a friend. A discussion with a friend about a problem you are facing might spark a moment of insight in which you are able to see how an event from earlier in your life might be contributing to your current patterns of behavior. This emotional release may help you feel better able to face your current dilemma.

- Listening to music. Music can be motivational, but it can also often spark moments of great insight. Music can allow you to release emotions in a way that often leaves you feeling restored.

- Creating or viewing art. A powerful artwork can stir deep emotions. Creating art can also be a form of release.

- Exercise. The physical demands of exercise can be a great way to work through strong emotions and release them in a constructive manner.

- Psychodrama. This type of therapy involves acting out difficult events from the past. By doing so, people are sometimes able to reassess and let go of the pain from these events.

- Expressive writing and journaling. Writing can be an effective mental health tool, whether you are journaling or writing fiction. Expressive writing, a process that involves writing about traumatic or stressful events, may be helpful for gaining insight and relieving stressful emotions.

- Various therapy approaches. Catharsis plays an important role in emotionally focused , psychodynamic , and primal therapies .

Remember that exploring difficult emotions can come with risks, particularly if these experiences are rooted in trauma or abuse. If you are concerned about the potential effects of exploring these emotions, consider working with a trained mental health professional.

Some researchers also believe that, although catharsis might relieve tension in the short term, it might also serve to reinforce negative behaviors and increase the risk of emotional outbursts in the future.

If you or someone you know is in emotional distress or crisis, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Hotline (formerly the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) is available 24 hours a day throughout the U.S. Call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org .

A Word From Verywell

Catharsis can play a role in helping people deal with difficult or painful emotions. This emotional release can also be an important therapeutic tool for coping with fear, depression, and anxiety. If you are coping with difficult emotions, talking to a mental health professional can help you to explore different techniques that can lead to catharsis.

Sandhu P. Step Aside, Freud: Josef Breuer Is the True Father of Modern Psychotherapy . Scientific American . 2015.

Encyclopeadia Britannica. Sigmund Freud. Psychoanalytic Theory .

Breuer J, Freud S. Studies on Hysteria . Harmondsworth: Penguin Books; 1974.

Sachs ME, Damasio A, Habibi A. The pleasures of sad music: a systematic review . Front Hum Neurosci . 2015;9:404. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00404

Childs E, de Wit H. Regular exercise is associated with emotional resilience to acute stress in healthy adults . Front Physiol . 2014;5:161. doi:10.3389/fphys.2014.00161

Orkibi H, Feniger-Schaal R. Integrative systematic review of psychodrama psychotherapy research: Trends and methodological implications . PLoS One . 2019;14(2):e0212575. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212575

Bushman BJ. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 2002;28(6):724-731. doi:10.1177/0146167202289002

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

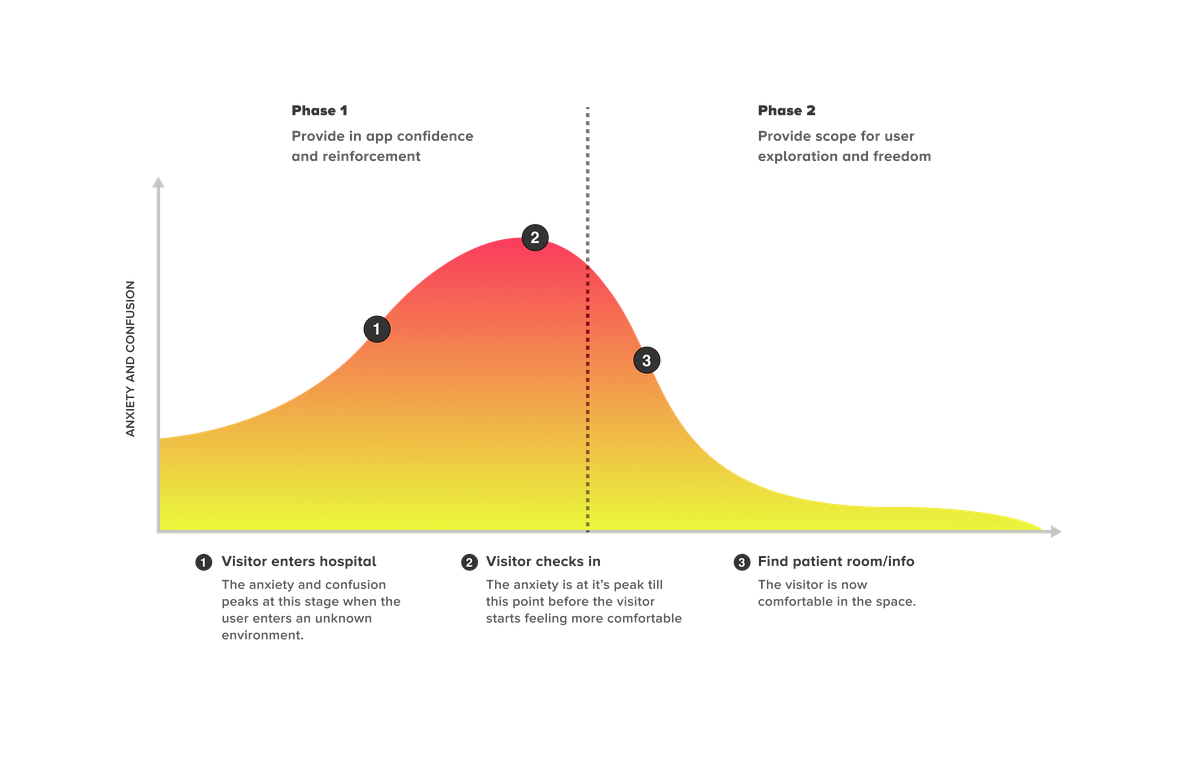

Emotional Journey

How users feel at each stage of the experience.

Jordi Olive Calderon

Angels Dimitri

What Is Emotional Journey ?

Emotional Journey is a powerful research practice to identify and visualize how users feel at each stage of the experience while they are using a product or service.

Mapping these metrics help the team to understand, test and deliver a positive experience for the users .

The emotions of the user can be captured by dots, emojis, pictures, colours, curves or other forms and shapes that represent the level of sentiment from each moment of the journey.

The Emotional Journey is usually used asan add-on to a User Journey Map or Service Blueprint practices.

Why Do Emotional Journey ?

Craft a better user experience:

- Understand users point of view

- Bring more humanity

- Identify faster the gaps on the journey where to improve the experience

- Reveal the ideal experience through the user’s eyes

- Understand what the users feel rather than what you think they feel

- Find new opportunities

- Empathise with the users

- Analyse the peaks and lows of the emotional rollercoaster

Improve business performance:

Ensure systems are customer focused

Knowledge of customers behaviours and needs

Drive ideation and innovation

Decide what should be the top priorities

Introduce metrics for what matters most for the customers

Eliminate where customer experience is most likely to fail

Imagine future service experience

Reflect customers needs and expectations while your business changes

How to do Emotional Journey ?

- Define what experience you want to map. User Stories and Prioritisation Matrix are useful practices that may help you to identify the user experience you want to address.

- Collect information from research and assumptions. It’s recommended to build a Persona or/and Empathy Map in order to visualise all the insights from the user perspective like their blockers, opportunities, needs, expectations, etc.

- If you identified more than one Personas then make sure you build an emotional journey for each of them because their journey and experience may be different.

- Start mapping the actions of the user during the journey in chronological order. It doesn’t have to be the entire journey, it may be just a part of it that you want to focus on during the experience.

- Use a line or curve graph to represent how the user feels during the journey.(↑Happy ↓Sad). It’s highly recommended to add a comment on what the user is feeling or thinking during the actions of the journey for a better understanding. You can add more than one comment per user action.

- Analyse the map and improve where it is needed based on the peaks and lows.

Notes & Observations

There are many different ways to build an emotional journey depending on the approach and the quality of the research.

You can first build the Emotional Journey and then use it to make the User Journey Map with Touchpoints, Pain points, Opportunities etc. or you can create it based on an existing Journey Map. The order of the practices doesn’t affect the final result.

Adding an horizontal line in the middle of the Emotional Journey will help you to see faster where the opportunity is.

It’s recommended to have one Emotional Journey per user. In case you’re using it for a Service Blueprint where different actors are involved then you can use the same space to represent the Emotional Journey for each of them. If this is the case, remember to use dissimilar colours to represent the different actors. (See the following example)

Having the User Story/Scenario, the Persona and his/her goal near the board helps to have a clear and common understanding of what the Emotional Journey is representing.

Emotional Journey can be used as a metric to compare As-is with To-be or Ideal User Journey experiences

It can also be used as a low fidelity experience prototype to test with users.

Look at Emotional Journey

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

emotional journey

Meanings of emotional and journey.

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

(Definition of emotional and journey from the Cambridge English Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

- Examples of emotional journey

Word of the Day

Punch and Judy show

a traditional children's entertainment in which a man, Mr Punch, argues with his wife, Judy. It was especially popular in the past as entertainment in British towns by the sea in summer.

Paying attention and listening intently: talking about concentration

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

{{message}}

There was a problem sending your report.

- Definition of emotional

- Definition of journey

- Other collocations with journey

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Tears of Joy as an Emotional Expression of the Meaning of Life

Bernardo paoli.

1 Accademia Delle Tecniche Psicologiche, Turin, Italy

Rachele Giubilei

2 Istituto per lo Studio Delle Psicoterapie, Rome, Italy

Eugenio De Gregorio

3 Link Campus University, Rome, Italy

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

This article describes a research project in which a qualitative research was carried out consisting of 24 semi-structured interviews and a subsequent data analysis using the MAXQDA software in order to investigate a particular dimorphic emotional expression: tears of joy (TOJ). The working hypothesis is that TOJ are not only an atypical expression due to a “super joy,” or that they are only an attempt by the organism to self-regulate the excess of joyful emotion through the expression of the opposite emotion (sadness), but that it is an emotional experience in its own right—not entirely overlapping with joy—with a specific adaptive function. Through the interviews, conducted in a cross-cultural context (mainly in India and Japan), we explored the following possibility: what if the adaptive function of crying for joy were to signal, to those experiencing it, the meaning of their life; the most important direction given to their existence? The material collected provided positive support for this interpretation.

Introduction

The emotions we experience and express have an adaptive function. They allow us to live better in the surrounding environment and respond accordingly to specific circumstances (e.g., fleeing from danger in response to feeling fear). They are the result of a process, of a largely unconscious process of self-regulation, which modulates their nature, intensity and manifestations. Responses to emotions are almost never as violent and powerful as they could be; as such, it happens rarely that a person “loses their mind” completely ignoring internal and external feedback signals. Emotions are also involved in automatic regulation ( Matarazzo and Zammuner, 2009 ). We make conscious attempts to modify our emotions in order to align them with our goals and interests by asking ourselves whether it is useful to feel fear when facing a certain difficulty. Thus, we can cope with fear by changing the perspective we use to observe the situation. Emotional regulations mean that one is able to modulate their form or mitigate their urgency. More generally, it means that one is able to assess demands from the environment and one’s own resources, and to respond to them in a flexible and adaptive way. Emotions, properly modulated and regulated, improve social interaction and individual wellbeing. Crying is an emotional expression that has both a self-regulatory goal (decreasing tension and recovering psychological balance) and the purpose of attracting the attention of others and requesting their help and support. Crying can also be the emotional expression of the “opposite” emotion: it can occur in situations in which a person experiences great joy. The dimorphous expression of tears of joy (TOJ) is a unique, non-mixed experience: the person experiences only joy, and not joy mixed with sadness. TOJ occurs in very significant situations in people’s lives, especially in correspondence with the perception of a deep connection with others and with episodes of personal success.

These are the findings from the literature, and the starting point for our qualitative research. This research, which started in an unusual way—due to a journey in India and in Japan taken by one of the authors—sought to explore the cultural influence on emotions and emotional expression, and, above all, on the possible links between TOJ and people’s definition of the meaning of life (MOL). Regarding the first point, we know from the literature that there are cultural differences that regulate emotional expression. In collectivist cultures (which exalt “the good of the group before the good of the individual”) social rules seem to lead people to avoid the direct expression of emotions, especially negative ones, which can undermine group harmony; on the other hand, the rules of individualistic cultures (which exalt “the good of the individual before the good of the group”) seem to be more tolerant of the expression of strong emotions (e.g., anger), because of values such as self-affirmation. Interestingly, the emotional expression of crying tends to occur more frequently in democratic countries with individualistic cultures, where there is greater wealth and political freedom. As for the second point—the pivot of the research—the literature says that people who experience a higher level of meaningfulness in their lives are more likely to experience positive moods and greater wellbeing. So, what if the adaptive function of TOJ were to signal the MOL to those experiencing it? In the literature, these two themes have never been related to each other. The present study aims to investigate a possible connection.

The Adaptive Function of Emotions

From an evolutionary perspective, emotions help humans cope with and adapt to different situations in life (cf. Lazarus, 1991 ; Plutchik, 2001 ). When triggered, emotions simultaneously activate different systems—such as perceptual, attentional, and neurophysiological systems—that predispose people to certain behaviors ( Tooby and Cosmides, 2008 ). For example, anger stimulates the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and triggers a flow of energy adequate to support a dynamic response to the situation, which may be self-defense or decompression; fear, on the other hand, induces a state of neurophysiological activation that allows the individual to respond to the initial stimulus through attack, avoidance, or escape. In the literature ( Fredrickson, 1998 ; Ruini, 2017 ) it has been found that “positive” emotions play important adaptive functions, on par with “negative” ones. Specifically, emotions such as joy, interest, or satisfaction have the ability to modify styles of thought and action, and may expand and improve people’s cognitive, behavioral, and social skills, which will in turn become lasting resources for the future. Fredrickson (1998) further argues that the important adaptive functions of positive emotions lie in their ability to counteract negative emotions and their consequences, leading to improved mental and physical health and motivation to work for one’s wellbeing.

The Regulatory Function of Emotions: Emotional Self-Regulation

It has been widely attested in the literature that an individual’s ability to self-regulate their emotions is a key feature in maintaining social functioning, physical wellbeing, and mental health (cf. Gross and John, 2003 ). Emotional regulation can be defined as the ability to cope with, monitor, and modulate one’s own emotional experiences, and refers to behavioral and cognitive processes that coordinate the intensity, duration, and expression of emotions in response to internal and external stimuli ( Gross, 1998 ; Gross, 2007 ). For example, when we find ourselves in circumstances that trigger fear, we can divert our attention away from those elements of the situation that most disturb us and focus instead on other aspects we perceive as less dangerous in order to regulate the intensity of the emotion felt in that moment. Gross (2001) distinguishes between antecedent-focused and response-focused strategies: antecedent-focused strategies refer to what individuals do before the emotional response tendencies are fully activated (e.g., choosing not to frequent places or people perceived as disturbing in order to avoid the onset of unpleasant emotions); response-focused strategies refer to what people do when the emotional response is in progress (e.g., striving to appear calm rather than angry, thus suppressing the expression of the emotion felt). The different strategies can down-regulate or up-regulate emotional experiences: while down-regulation strategies tend to attenuate the emotional response, up-regulation strategies contribute to enhancing and prolonging it, whether it be a positive emotion triggered by a pleasant event, or a negative emotion generated by an unpleasant event.

Many works in the literature have focused on the regulation of negative emotions, while few studies have focused on understanding how people regulate positive emotions, such as happiness or pride. Positive emotion regulation refers to how humans modulate responses to stimuli in order to enhance and maintain the positive emotional experiences experienced at a given time ( Bryant and Veroff, 2007 ). Some studies (cf. Langston, 1994 ) show that, when experiencing very positive situations (e.g., victory in a competition; achievement of an important goal) people can implement behaviors designed to protect their state of happiness: for example, sharing good news with friends or relatives is a way to prolong the positive experience (capitalization). Positive emotional regulation strategies include savoring ( Bryant, 1989 ), which is the ability of humans to enhance and intensify positive experiences in their lives ( Bryant and Veroff, 2007 ). Bryant et al. (2005) theorizes three types of savoring: savoring in relation to an impending positive situation (e.g., anticipatory excitement before an enjoyable event); savoring that prolongs and reinforces the positive event experienced in the present moment (e.g., sharing the experience with people important to us); and savoring intense memories of positive experiences in order to relive the emotions associated with them (e.g., remembering the best moments of an event). Bryant and Veroff (2007) , identified several strategies that people use to enhance their savoring ability and that are expressed at cognitive, behavioral, and interpersonal levels. These include: memory building, which consists in creating a lasting memory of an event (for example, taking a mental picture of an event, or taking a diary); self-congratulation every time we manage to achieve something important in our lives in order to amplify positive feelings; sharing positive emotion with others; comparing the experience lived with a worse one, to appreciate it more; attentional absorption, which means to stay focused and engaged in the present moment and in experience that we are living, without turning our thoughts to the past or future; sensory-perceptual sharpening, which consists in focusing on the sensory aspects that are stimulated in a certain experience (e.g., smells or sounds); behavioral expression, which covers all those physical expressions of happiness (laughing, jumping, clapping) that contribute to generating a positive cycle of pleasure; temporal awareness, for example, reminding ourselves that the experience will not last forever may spur us to enjoy it even more; counting blessings, i.e., experiencing gratitude for having had the opportunity to experience something positive; avoidance of kill-joy thinking, which refers to not focusing exclusively on negative aspects when we go through a difficult time. Use of savoring strategies is positively associated with variables related to individual wellbeing (e.g., self-esteem, life satisfaction, self-reported optimism), whereas lack of savoring skills is linked to depressive feelings, hopelessness, and anhedonia ( Bryant, 2003 ; Joormann and Stanton, 2016 ).

Interpersonal Emotion Regulation

Humans often seek to moderate their emotional states through the comfort and support of other individuals, thus engaging in a process referred to as interpersonal emotional regulation ( Zaki and Williams, 2013 ). When people listen to and support someone’s feelings by showing empathy, solidarity, and sharing, they are actually helping them to regulate the intensity of the emotions they experience. Zaki and Williams (2013) identify two different processes that can support interpersonal emotional regulation: response-independent and response-dependent. The latter is based on the quality of feedback received from the person with whom the emotion is shared; in other words, when people express their sadness or joy to another person, they are only satisfied if that person responds favorably to the request to share. If the interlocutor shows indifference, then emotional regulation does not succeed. Response-independent processes, meanwhile, do not imply that the person with whom emotional states are shared must respond in a particular way: the fact of having talked with someone about one’s emotions, giving them a label and identifying their source, is enough in itself to allow people to feel regulated. As is the case in self-regulation, different strategies can be used in interpersonal regulation, depending on the goal one wants to achieve for a given emotional state. We refer to down-regulation processes when people respond in a way that attenuates and minimizes the intensity of the emotional experience shared by the communicative partner, while also weakening behavioral responses ( Krompinger et al., 2008 ). In an experimental study, Pauw et al. (2019) asked participants to watch a video of a man crying over his partner’s cheating and asked them to record a supportive video message for him. Analysis revealed that when the situation required immediate emotional down-regulation (such as having to be ready to face an upcoming job interview), participants attempted to regulate the other through disengagement from the emotional experience by implementing distraction and suppression strategies. For example, by saying “Try not to think about her for now,” or “Don’t let your emotions take over.”

When, on the other hand, a person shares positive events with significant others (relatives, friends, partners) and they respond in a way that maximizes and prolongs the positive feelings and benefits experienced, we refer to the phenomenon of capitalization ( Gable et al., 2004 ; Gable and Reis, 2010 ; Reis et al., 2010 ). Gable et al. (2004) found that communicating positive situations with significant others is associated with increased wellbeing and daily positive affect. The authors also showed that if significant others respond actively and constructively to capitalization attempts, benefits increase: in couples, this translates into greater wellbeing in some important aspects of the relationship, such as daily marital satisfaction and intimacy.

Crying in Literature

Crying is one of the most common and universally recognized forms of expression through which people manifest and share their emotions. Crying results from the interaction between psychobiological, cognitive, and social processes (cf. Vingerhoets et al., 2000 ) and serves several functions. It has been suggested in the literature that crying may lead to a decrease in tension (cf. Vingerhoets et al., 2009 ) and promote the recovery of psychological balance ( Rottenberg et al., 2003 ; Hendriks et al., 2007 ), although the empirical evidence supporting these hypotheses is conflicting. Some authors have investigated the interpersonal effects of this emotional expression. For example, Hendriks et al. (2008) conducted a survey with the purpose of studying how individuals respond when faced with a crying person, and had participants read six short vignettes depicting social situations. Specifically, three vignettes depicted unpleasant situations (e.g., talking to someone at a funeral or causing a car accident), while the other three depicted pleasant situations (e.g., meeting someone who had just become a parent). In each vignette there was a main character for participants to identify with, and another person who may or may not be crying. In most cases, participants reported that if they were faced with a crying interlocutor, they would exhibit more emotional support and fewer negative feelings toward him or her. Crying could therefore serve as a means of attracting attention, conveying requests for help and support, stimulating others to provide emotional support and thereby facilitating social bonding ( Frijda, 1997 ; Kottler and Montgomery, 2001 ).

Cultural Differences in Emotional Expression

Several studies (cf. Matsumoto, 1989 , 1990 ; Safdar et al., 2009 ) have investigated cultural differences that may influence the display of emotions. In this regard, Ekman and Friesen (1969) ; Ekman (1972) proposed the existence of social rules, referred to as display rules, which govern the manifestation of emotions within different cultural groups, and which are learned by individuals through the socialization process. These rules direct emotional expression based on whether it is more or less acceptable within a given culture ( Matsumoto et al., 1999 ) and establish how, and in what context, a person should express their emotions. The studies by Ekman (1972) and Friesen (1972) provided the first, which has become a milestone in the history of psychology, provided the first evidence of the existence of the “display rules.” The authors highlighted how American and Japanese people have a different way of expressing their emotions depending on the context: if a stranger was present during the viewing of a movie with the participants, the Japanese (unlike Americans) tended not to express negative emotions, disguising them with smiles. The presence of a stranger activated a set of unwritten, culturally learned rules in Japanese participants that regulated the expression of negative emotions. Ekman and Friesen’s study was later resumed by Matsumoto (1992) , who compared the responses of American and Japanese people in reference to a task of facial expression recognition, finding results in keeping with those of previous studies. In the same research, Matsumoto found that Japanese participants were less able to recognize negative emotions than American subjects, while he found no significant differences in the recognition of positive emotions. To account for these differences, the author investigated cultural differences between the United States and Japan, focusing specifically on the concepts of individualism and collectivism. In cultures with an individualistic features (like most Western cultures), the primary values are those of individual autonomy, self-interest and success; it can be hypothesized that this is why levels of conformity to the group are lower and independence is greater instead: emotions can be experienced primarily as personal experiences, the expression of which is an individual’s right. In these cultures, for example, the manifestation of anger is tolerated and considered functional for the individual, as long as it is expressed in socially appropriate ways ( Eid and Diener, 2001 ). Collectivistic cultures, on the other hand, would foster a greater level of conformity within the group, and collective needs would tend to take precedence over individual needs. In general, these cultures seem to urge the individual to maintain cohesion and harmony in the group, rather than to foster individual affirmation ( Matsumoto, 1991 ; Noon and Lewis, 1992 ); where emotions are experienced as interactive experiences, reflecting the social context, their expression needs to be controlled. In particular, negative emotions may threaten group cohesion and are therefore discouraged. The expression of emotions such as anger or contempt would not be considered acceptable, as they threaten authority and harmony in the group ( Miyake and Yamazaki, 1995 ). Regarding positive emotions, in individualistic cultures there would be a great attention to the pursuit of happiness and its individual expression: not expressing positive emotions could be considered a failure, and unhappiness would tend to have a strongly negative connotation. Conversely, in collectivist cultures, display rules might also filter out the expression of positive emotions, as expression is sometimes considered undesirable (see Eid and Diener, 2001 ).

A study by Safdar et al. (2009) examined the display rules of seven basic emotions in three different populations: American, Canadian, and Japanese. The goal of the research was to compare the display rules of emotional expression, both across and within cultures. The authors hypothesized that Canadians and Americans showed more approval toward the expression of both negative emotions such as anger and disgust, as well as positive emotions such as happiness and surprise, than Japanese participants, and that all three populations did not show particular differences regarding the expression of emotions such as sadness or fear. In keeping with the first hypothesis, the results showed that Japanese subjects expressed fewer negative emotions than Americans and Canadians, and showed significantly lower mean scores in the expression of positive emotions than Canadians. It was also found that there was no difference between Japanese and North Americans in the expression of emotions of sadness or fear.

Regarding the emotional expression of crying, some authors have conducted cross-cultural studies (see Kraemer and Hastrup, 1986 ; Vingerhoets and Becht, 1997 ). Williams and Morris (1996) investigated the crying behaviors of 448 participants from Great Britain and Israel, and the results showed that Britons cried more frequently than Israelis and that women cried more intensely and more often than men. Van Hemert et al. (2011) conducted a study to examine the tendency to cry in 37 countries, including Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Europe, the Middle East, North America, Oceania, and South America. Analyses showed that crying is not significantly related to perceived distress, but is related to subjective wellbeing; that is, happier countries report more expressions of crying. At for the frequency, the results also showed that crying occurs more frequently in democratic countries, with an individualistic culture, where there is greater wealth and political freedom.

Tears of Joy