- Home Kāinga

- Our Story Ngā Kōrero

- Our Tours Ngā Haerenga

- Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Space Place Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Nairn Street Cottage

- Cable Car Museum

- Careers Umanga

- What’s On Ngā Kaupapa Whakatairanga

- Museum Blog

- Our Venues Ngā Wāhi

- Venues at Wellington Museum Ngā Wāhi i Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Birthday Parties Ngā Pāti Rā Whānau

- Recommended Caterers Ētahi Kaitaka Kai

- Education Blog Rangitaki Mātauranga

- Space Place

- Wellington Museum

- Space Place Wāhi Haumaru

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Wāhi Haumaru

- Support Us Tautoko

- Museum Blog Te Kāpata Te Curio

Remembering the 81′ Springbok Tour

40 years on, we look back and talk to two Wellington residents who remember those turbulent times.

“All for the sake of a Rugby game. Doesn’t make sense does it?” – Liz Roberts

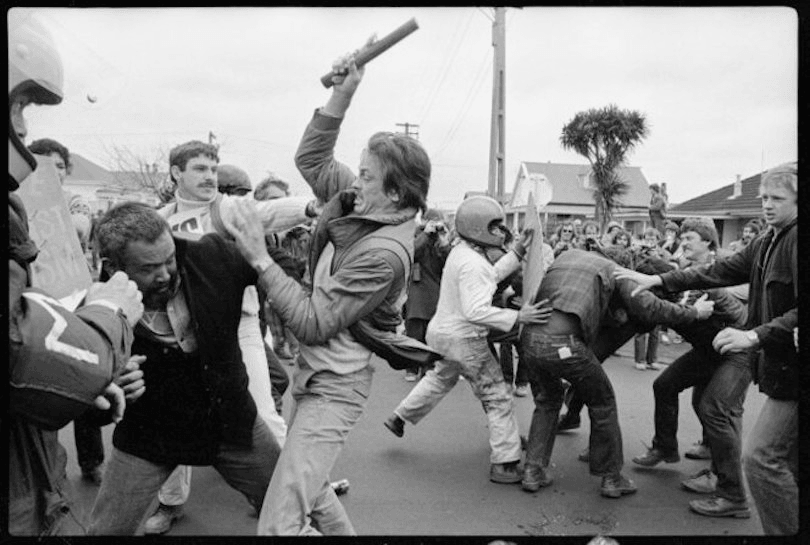

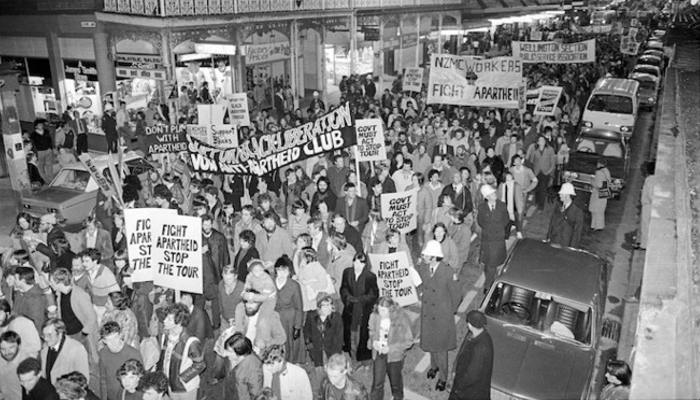

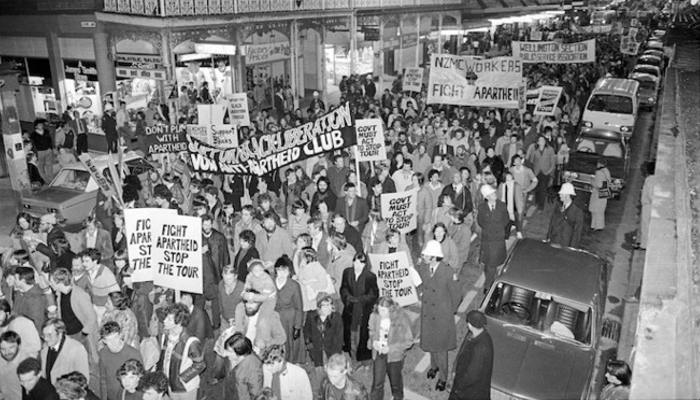

During the winter of 1981, violent clashes between rugby supporters, protesters and the police erupted all over Aotearoa in one of our country’s most tumultuous periods. The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home.

On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa’s Consul to New Zealand.

This was the first time police had used batons against protestors, and the violence horrified many New Zealanders. Former Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s prediction eight years earlier that a tour would result in the ‘greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known’ seemed to ring true.

Wearing helmets like this one, 7000 protesters gathered in central Wellington and around Athletic Park on 29th of August 1981 to stop pro-tour supporters from gaining access to the second test match. Once again the police intervened, this time using long batons, with many protesters injured as a result. This helmet was worn by Anne Bogle during other anti-tour protests.

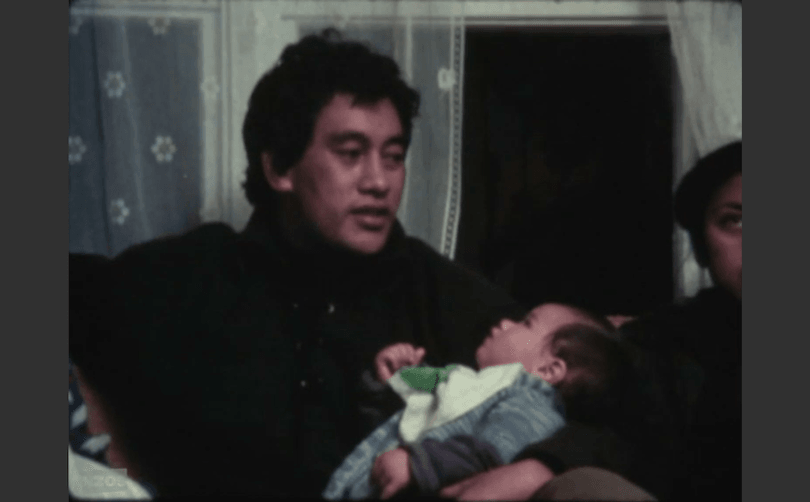

The Merata Mita Estate permitted us to use the Wellington footage from PATU! (1983) – the powerful documentary directed by Merata Mita which shows the harrowing events of the 1981 Springbok Tour.

Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision meticulously restored and preserved the original documentary for the 40th anniversary. With their approval, we were able to use their newly restored and remastered version for these videos.

Liz Roberts lived on Te Wharepōuri Street in Berhampore, close to Athletic Park, and recalls the events of the 2nd Test on August 29th, 1981, where she saw protesters clash with Police on her street.

Anne Bogle was a young Victoria University student studying Law and History in 1981 – and attended a number of Anti-Tour protests in Wellington – she took part in the protest group that blocked the Wellington Motorway on July 25th and the infamous Molesworth Street incident a few days later on July 29th. The protester helmet she used during the anti-tour demonstrations is currently displayed at Wellington Museum.

Thank you to the Merata Mita Estate for their permission to use parts of the film and also to Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision for their great mahi on the preservation and restoration of this important piece of film taonga .

Also thank you to Anne Bogle and Liz Roberts for sharing their stories.

Pin It on Pinterest

Springbok tour research: how does history interpret?

This weekend marks 40 years since the notorious flour-bomb incident at Eden Park during the 1981 Springbok tour.

Violence erupted outside the stadium grounds as protesters and police faced off, while others threw flour bombs and flares on the field to stop the game.

Although apartheid was a major factor behind the unrest, protesters were also actually critiquing wider New Zealand society, says sports historian Sebastian Potgieter .

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

- Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour.

Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells Kathryn Ryan.

"The South African government had a very strict information policy in place, which means that a lot of information, particularly that which was critical of the apartheid government, didn't actually make it through to the general public.

"In the wake of that tour, South African rugby came to be seen as somewhat of a symbolic liability and a lot of countries didn't want to play against South Africa.

"They felt that if the '81 tour is anything to go by, there was a likelihood of very extreme protests taking place in those countries which did host South Africa."

Dr Potgieter found it interesting to hear how vividly New Zealanders remembered the tour as it's not often spoken about in South Africa.

"We sort of know about incidents like the 'flour-bomb' test, but in general, South Africans don't know too much about this tour.

"It's still a matter which polarises opinions, so people have a lot to say about the tour, and have a lot to say about where they were, what they were doing during that tour."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter Photo: Supplied

It wasn't just apartheid that people were upset about in 1981 - protesters were also taking a stand against the deportation of Pacific Islanders and overstayers and the annexed Māori lands, Dr Potgieter says.

"We very selectively remember the past. It's impossible to remember the past in its entirety ... so certain parts of the past become elevated and contemporarily what we see in New Zealand.

"If you go back and look at some of the recollections of protesters who are writing shortly after the tour, we see that they say yes, apartheid was a problem, it was certainly what mobilised protests.

"But in the process of protesting a lot of people ... linked the protests to a lot of the racial discrimination that was happening in New Zealand at that time.

"It's more complex than simply saying this was an anti-apartheid protest and the anti-apartheid side of things is what's elevated at the moment, but it certainly doesn't define what those protests were about."

The demonstrations were also used as a platform to discuss the problematic aspects of rugby culture such as violence, gender stereotyping and alcoholism, he says.

People also need to remember that many New Zealanders supported the tour, Dr Potgieter says.

"Every single stadium during that entire tour was sold out and that there were large numbers of New Zealand television audience who tuned in to watch every game.

"We also see that a lot of New Zealand's far right and extremist groups actually have their biggest sort of phase of public acceptance or public profile when the question of South African tours cropped up in New Zealand.

"When those tours became put into jeopardy, these extremist groups or far right groups - whatever one wants to call them - received tremendous support in New Zealand."

Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a teaching fellow at the University Of Otago's school of physical education, sports and exercise sciences.

- Sebastian Potgieter

- anniversary

To embed this content on your own webpage, cut and paste the following:

<iframe src="https://www.rnz.co.nz/audio/remote-player?id=2018811821" width="100%" frameborder="0" height="62px"></iframe>

See terms of use .

Recent stories from Nine To Noon

- Screentime: Love Lies and Bleeding, The Gentleman

- Helping pre schoolers build language across the day

- Tech: AI + women's jobs, Apple's anti-trust lawsuit, AI

- Around the motu : Kim Bowden covering Queenstown/Wanaka

- Book Review: Emma Hislop reviews Memory Piece by Lisa Ko

Get the RNZ app

for easy access to all your favourite programmes

Subscribe to Nine To Noon

Podcast (MP3) Oggcast (Vorbis)

- Adding a Story

- Enterprise »

- Your Story »

- Audio Walks »

Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981

In 1981 the South African rugby team, the Springboks, toured New Zealand. The protests against this tour reached a level unparalleled in New Zealand history. This reflected the fact that both the Māori protest movement and anti-apartheid movement had developed significantly ¹. The 1981 tour was the last time the All Blacks and South African rugby teams would play while South Africa was still under an apartheid system. A 1985 tour to South Africa was cancelled after a legal challenge, though a group of rebel players went to South Africa the following year.

Opinion on the Springbok Tour NZ July 1981 From Malcolm McKinnon (ed.), New Zealand historical atlas , David Bateman, Auckland, 1997.

When the Springboks arrived in Nelson on Thursday August 20, 1981 – they were met with strong protest and a city divided over the question of apartheid. There were clashes between pro-tour supporters, anti-tour protestors, and the police. There had already been demonstrations in Christchurch and the Timaru game had been cancelled.

Nelson's mayor Peter Malone's decision to provide an official welcome to the team led to a packed meeting in the Council Chamber - protestors cried “shame” and “racist”, to which the Mayor responded saying "he was “sick and tired” of attempts to link him to apartheid – and that his decision to welcome the team was in a tradition of extending courtesy to visitors. Calls came for Councillors to state where they stood on the Tour - Councillors Craig Potton, Elma Turner and Dorothy Matthews quickly stood up to condemn the tour – others backed the Mayor’s stand.²

Springbok Tour protestors Nelson Church Steps August 1981. Nelson Mail Collection: 6424_FR16 Nelson Provincial Museum

The official welcome at the Rutherford Hotel went off without incident, and was attended by Mayor Malone, Deputy Mayor Pat Tindle, Councillor Malcolm Saunders, and Nelson MP Mel Courtney.

On the morning of the Saturday game roads leading to Trafalgar Park were cleared, barricades were set up and police massed at the Maitai Bridge to control access leading to the park. At the Rutherford Hotel where the Springbok team was staying, about 100 protestors gathered to form a picket line and got into an altercation with police where several were arrested.

The main gathering of protestors ended up at the church steps , where anti-tour banners had appeared over the Nelson Cathedral tower. After that protest they moved down Trafalgar Street as far as Halifax Street where the police diverted the marchers down to Paruparu Road where they continued to chant loudly across the river to Trafalgar Park where supporters of the game were gathered for the match.

The Springboks racked up 83 points during the 80 minutes – with first-five eighth Naas Botha accounting for 31 of them. Nelson Bays coach Mervyn Jaffray was not present to see his team get taken apart, as he elected to stay home on account of his moral opposition to the tour – instead receiving occasional score updates from his wife as he got to work planting in their vegetable garden.

Police said about 30 people were arrested in total throughout the protest, mainly from Christchurch and Wellington.

The anti-apartheid movement in South Africa was buoyed by events in New Zealand. Nelson Mandela recalled that when he was in his prison cell on Robben Island and heard that the game in Hamilton had been cancelled, it was as ‘if the sun had come out’.³

September 2021

- Michelle Bryant

- anti-apartheid

Sources used in this story

- Keane, Basil 'Ngā rōpū tautohetohe – Māori protest movements - Rugby and South Africa', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand (accessed 7 September 2021) http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/nga-ropu-tautohetohe-maori-protest-movements/page-4

- Newman, T. (2021, August 21) Springbok Tour 'a watershed moment' for Nelsonians on both sides of the divide. Nelson Mail on Stuff : https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/126109153/springbok-tour-a-watershed-moment-for-nelsonians-on-both-sides-of-the-divide

- 'All Blacks versus Springboks' (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 4-Feb-2020 https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/1981-springbok-tour/all-blacks-vs-springboks

Want to find out more about the Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981 ? View Further Sources here .

Related Stories

- The history of Nelson rugby

- New Zealand's first Rugby club

- First game of rugby

- Nelson's Church steps

- Trafalgar Park

Do you have a story about this subject? Find out how to add one here.

Comment on this story

Post your comment.

Thank you for writing this article. This brings back a lot of memories. Some sad. From my recollection. In Nelson there were no pitch invasions or other disruption of the match. The protesters got as far as the Trafalgar Street Bridge then split into three groups: the Paruparu road group (described above), another in Millers Acre & the group that roamed the streets in the Wood near the park. At the end of the game the protesters had dispersed when the rugby crowd of about 5,000 made their way home after that drubbing of 83-0. I don't remember the "city being divided over Apartheid" there appeared to me to be a lot of Nelsonians who were neither for or against the tour but sat in the middle - didn't have an opinion either way. The papers said at the time that at the airport when the Springboks arrived that there were a handful of protesters, but they were outnumbered by tour supporters and Nelson people who had just gone out to 'have a look'. What concerned people, especially my mother, was the explosive device found in the bar of the Rutherford Hotel and the other explosive devices found in the foyer of the Post Office. The other thing that I remember was what was called a 'tuna scarer' being used and nail clusters being thrown under the tour bus. It was a frightening time.

Posted by Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981, 19/09/2023 11:35pm (6 months ago)

No one has commented on this page yet.

RSS feed for comments on this page | RSS feed for all comments

Further sources - Springbok Tour in Nelson 1981

- Cameron, D. (1981) Barbed wire Boks. Auckland, NZ. Rugby Press Ltd. https://www.worldcat.org/title/barbed-wire-boks/oclc/13536912

- Chapple, G. (1984) 1981: the tour. Wellington, NZ. A.H. & A.W. Reed. https://www.worldcat.org/title/1981-the-tour/oclc/17222312

- Meurant, R. (1982) The Red Squad story . Auckland, N.Z. : Harlen, 1982 https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/13419904

- Newnham, T. (1981) By batons and barbed wire. Auckland, NZ. Real Pictures Ltd https://www.worldcat.org/title/by-batons-and-barbed-wire/oclc/1153492160

- McKinnon, M. (ed.),( 1997) New Zealand historical atlas. Auckland, NZ, David Bateman https://www.worldcat.org/title/bateman-new-zealand-historical-atlas-ko-papatuanuku-e-takoto-nei/oclc/39014539

Shears, R. & Gidley, I. (1981) Storm out of Africa : the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand . Auckland, N.Z. : Macmillan https://tepuna.on.worldcat.org/v2/oclc/12664077

- 'Opinion around New Zealand on the 1981 Springbok tour' (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 4-Feb-2020 https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/opinion-on-the-springbok-tour-around-new-zealand

- 'Police cry wolf claims Hart head' ( 1981, August 25) Nelson Evening Mail, p.2

- 'Poetry read to marchers' (1981, August 24) Nelson Evening Mail, p.10

- 'Blown his cover' (1981, August 21) Nelson Evening Mail, p.1

- 'Angry scenes' (1981, August 21) Nelson Evening Mail, p.1

- It's just a game. Retrieved from Nelson Provincial Museum 7 September 2021: http://www.nelsonmuseum.co.nz/rugby-150/its-just-a-game

Web Resources

- Springbok tour 1981. National Library Services to Schools. Retrieved 7 September 2021: https://natlib.govt.nz/schools/topics/57fd9962fb002c638c0066d7/springbok-tour-1981

Footer Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 New Zealand License

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

- newzealand.govt.nz

The Spinoff

Ātea December 28, 2021

Three things you didn’t know about the 1981 springboks tour.

- Share Story

Summer read: This year marked the 40th anniversary of the rugby tour that divided a nation. While countless books and articles have been written about that time, some important details have faded with age. Leonie Hayden looks back at three of them.

First published July 22, 2021

Merata Mita’s documentary Patu! opens with a group collecting signatures on the street in Auckland to petition the government to stop the upcoming Springboks’ tour of New Zealand. A young passer-by starts arguing with the organisers, asking how would they feel if a group of “wogs” or “Blacks” came over here. One group member explains that she’s married to a Black South African man. Undeterred, the man continues his tirade about what would happen if “they” were in charge.

It’s 1981 and Mita’s grainy film footage captures one of those most divisive periods in our history since the New Zealand Wars. It was a battle that played out on the rugby field, in the streets, within the halls of parliament and at kitchen tables all over the country. But the fight for New Zealand to take a stand against South Africa’s apartheid regime was far from new.

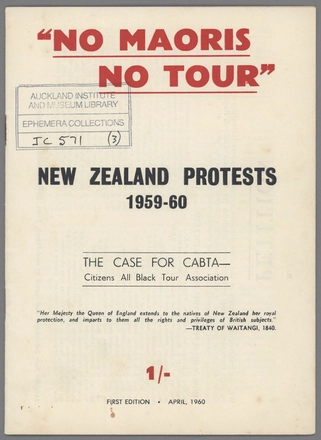

The New Zealand Rugby Football Union had left rugby legend George Nēpia and other giants of the game at home in 1928 to conform with South Africa’s segregation laws. In 1959, the Citizens’ All Black Tour Association had tried to demand “No Maoris, no tour” when Māori players were excluded from the team’s 1960 visit. They weren’t successful then, but Māori players would go on to tour South Africa as “honorary whites” in 1970 and then in 1976 – the same year as the Soweto uprising that saw hundreds of children and student protestors murdered by police.

While Robert Muldoon campaigned on sports and politics being kept separate, deftly side-stepping the Commonwealth members’ Gleneagles agreement , the world had very much decided the two were connected. Black African nations boycotted the 1976 Montreal Olympics in protest of our ongoing engagement with South Africa. New Zealand was becoming a pariah.

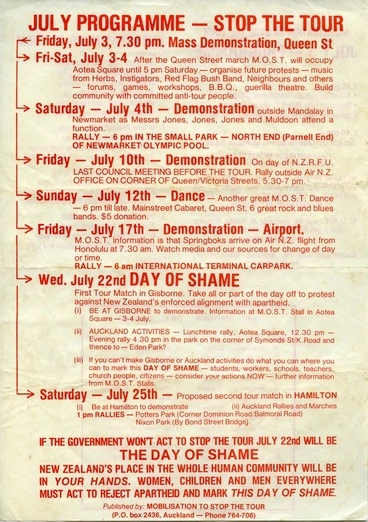

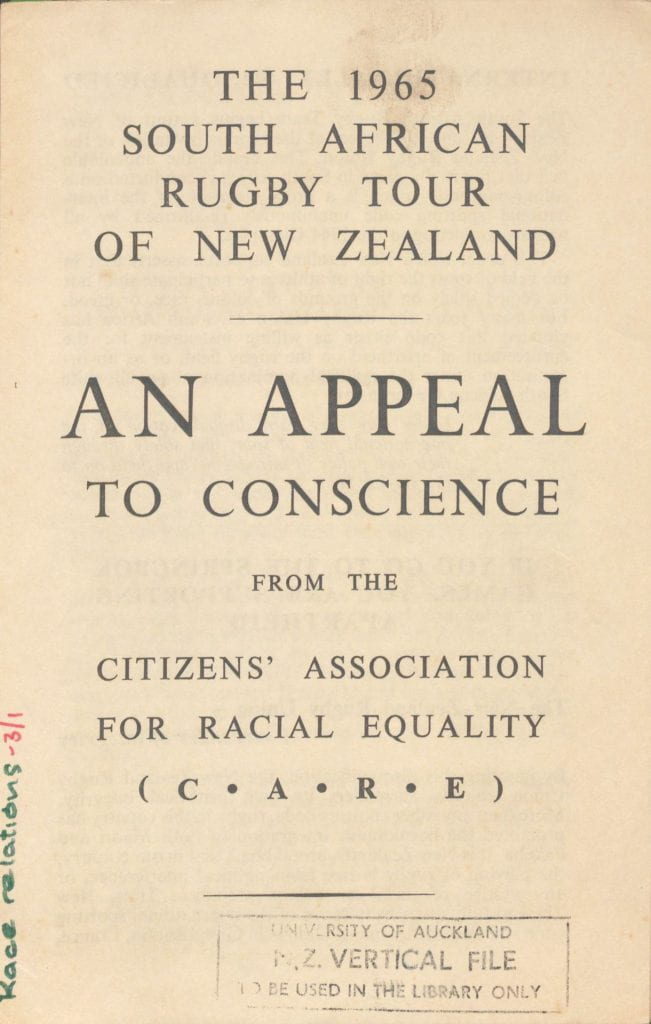

And so when the 1981 tour was announced, anti-apartheid groups such as Halt All Racist Tours (HART), Citizens Association for Racial Equality (CARE) and the Patu Squad (led by Hone Harawira, Donna Awatere, Josie Keelan and Ripeka Evans) began a national campaign to stop it in its tracks.

Ultimately, the demonstrations and petitions to Muldoon’s government – plus a national poll showing only 46% public support for the tour – fell on deaf ears and the South African team were officially welcomed to New Zealand at Te Poho-o-Rawiri marae in Gisborne on July 19, 1981.

Tā Graham Latimer’s wero

It was a pōwhiri with teeth.

The welcome for the Springboks took place at the same time as Māori activists were spreading glass across Gisborne’s Rugby Park ahead of the first game. The speakers that evening comprised Te Poho-o-Rawiri kaumātua, dignitaries of the Tairāwhiti Māori council, and the president of the New Zealand Māori Council, the late Sir Graham Latimer .

To many the welcome would have looked like a sign of a generational divide – conservative assimilationists on the marae versus activists on the field – but Latimer ensured the pōwhiri wasn’t an occasion that ignored or played down what was at stake. In fact, he very politely told Springboks captain Wynand Claassen and his team they wouldn’t be welcome again while apartheid remained in South Africa.

Per tradition, it was Latimer’s role as the New Zealand Māori Council president to extend a greeting to any international group being welcomed onto a marae. The speaker before him, Tom Fox, had emphasised with some pride, and to much applause, that the Tairāwhiti branch was the only Māori council that actively supported the tour.

Latimer, however, was less effusive. “I am fully conscious of the fact that I do not have a complete mandate to make this welcome,” he began. “Seven out of the nine district councils that make up the New Zealand Māori council are opposed to the tour, and one is undecided.” A long pause, silence from the crowd.

“Fifty-four per cent of the general public of New Zealand has expressed opposition to your tour. That’s in a poll. The last time such a tour was mooted, only 16% were against the tour. That you have come has been seen by some as a major victory but it must be recognised that if there were only another 6% against the tour, there would be neither a political party not a rugby union game enough to extend an invitation to you.”

He continued: “There can be no doubt in my mind that we will not be making another such welcome on a Māori marae – I emphasise that point – unless your government can show it is prepared to change its policies on apartheid. We hope we can look forward to a time in the not too distant future when you could be welcomed on any marae. It would be a pity if this could be looked upon as the last international tour by South Africa.”

Latimer finished by giving an especially warm mihi to Errol Tobias, the first player of colour to tour with the Springboks. “I believe he represents hope for 18 million South Africans, for whom there appears to be little hope.”

The genius of Latimer’s challenge was in its statesmanlike delivery. While much of his speech was received with (presumably) shocked silence, he was still rewarded with a huge round of applause at its conclusion, even though he had just told those gathered they would not be welcome in future under the same circumstances. The extraordinary recording of that evening, housed in the Ngā Taonga archive , captures a mild-mannered assassin executing an entire squad with diplomacy.

Naturally we have no way of measuring the effects of that speech on either the Springboks or apartheid. But it may have been the last time the issue was discussed politely.

Police violence was far worse than they’d like you to remember

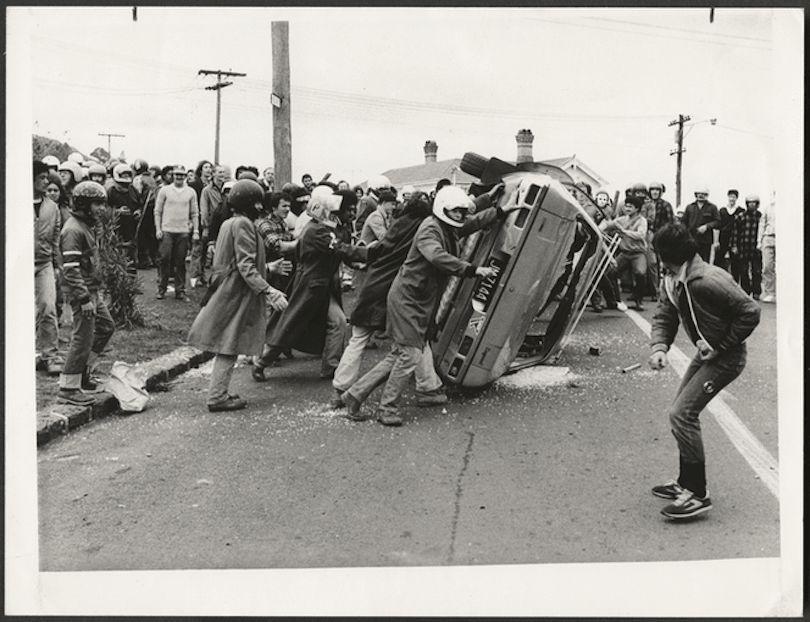

Nicknamed the Day of Shame, July 22 saw the Springboks’ opener against Poverty Bay. Three hundred protestors marched to Rugby Park in Gisborne via a nearby golf course and attempted to breach a fence. Rugby fans jumped into action and a brawl broke out between the two groups. Police arrived to break up the fighting, and only two men managed to run onto the field. Thirteen were arrested and many were hurt in the resulting brawl, but it was nothing compared to the violence that was to come.

Over the course of the next two months, police, in particular the infamous Red and Blue riot control squads, would become more and more comfortable with using extreme violence against unarmed protestors, causing serious and sometimes permanent injuries. Pro-tour rugby fans were also brutal in their retaliation.

Singer and journalist Moana Maniapoto, then a first-year law student at the University of Auckland, remembers when the fence came down at the second game in Hamilton on July 25. “Everyone’s leaning on it, pushing and pushing it, and then the next minute the fence came down and you just heard this ‘Run!’ You’re just swept along. So then I’m in the middle thinking, ‘what am I doing here? They’re gonna kill us!'”

She recalls looking up at thousands of angry faces in the stands. “They were totally rabid. Screaming, yelling and throwing cans of beer at us.

“The police arrived, just the ordinary cops, not the Red Squad, and I actually thought, ‘oh this is good, surely they’re not gonna let us get murdered’. Then the commissioner came on and said the match has been called off and there was this huge roar from the crowd. At first it was like, ‘yay!’ and then ‘oh my god. How the hell are we gonna get out of here?’”

Maniapoto, along with land protector Eva Rickard and another friend, managed to escape into the surrounding streets. “The cops were sporadically placed so you had to make a run for it to the gate. Then the cops recognised Eva and they were abusing the shit out of her. But we got out, and we were very lucky, my friend’s father heard on the radio that the match had been cancelled and he circled until he found us. A lot of people got attacked.”

Marx Jones and Grant Cole flour bomb Eden Park in a hired Cessna.

She would go on to attend protests in Rotorua and at the third test in Auckland – the latter resulting in a violent clash between police, protestors and rugby fans on the streets of Mount Eden. “Red Squad came out of nowhere and nutted off at everyone. I was with the least militant bunch when they charged. We were just standing there. Couldn’t believe it. I was batoned, kicked by heavy police boots while on the ground. Shock for a young freshie like me. They just smashed into us and left people lying on the ground in their wake.”

For further proof you need only watch the violence through Mita’s lens. The dull thud of police batons hitting flesh and human skull, and the wails of the injured, some of them young teenagers, is the haunting soundtrack for nearly half the film.

Maniapoto scoffs at the selective memory that it was “New Zealand” who took a stand against apartheid. “It’s held out as a landmark, framing New Zealand as a global social justice advocate. It wasn’t New Zealand; it was people power. It was activists, people from across all walks of life, and there were far fewer of us than there were in the stands.”

She talks abut the Nelson Mandela exhibition hosted at Eden Park in 2019 – a strange venue considering the violence that played out on the surrounding streets 38 years earlier. She says at the launch none of the speakers from the New Zealand Rugby Union came close to admitting they’d been wrong, or offering an apology. Instead everybody spoke proudly about the stand taken by the protestors. Says Maniapoto: “They’re starting to rewrite the history!”

The good bishop saves the Patu Squad

It was at the last test at Eden Park on September 12 that a young Hone Harawira, one of the leaders of the predominantly Māori and Pasifika Patu Squad, was finally caught.

Harawira and a handful of others had been arrested at Waitangi earlier in the year, and although they had been denied bail, they were turfed out of the cells for causing a ruckus and told when to attend their court date. They didn’t show up.

The group had outstanding warrants for their arrest before the tour even began.

“It must have got out to the police that we were all going to be involved in the tour, and one by one we were all picked up. One of the brothers, they got him before it started! So he spent the whole of the tour in Mt Eden,” Harawira chuckles.

Harawira says he was caught early on after the test that ended with Marx Jones’ aerial flour bomb attack , so hadn’t been involved in the upturning of a cop car, or the violence that erupted on an unprecedented scale outside Eden Park. Nevertheless, Harawira was charged with the assault of a police officer who’d had both collar bones broken.

“It wasn’t me but they wanted someone to pin it on so they pinned it on me.”

He says he had seven charges against him. “They were serious charges. Three charges of participating in a riot and four charges of assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. Which all carried a total of something like 98 years.”

Justice being neither blind nor in a hurry, Harawira wouldn’t stand trial for another two years, alongside many others who he notes were mostly brown, despite the vast majority of protestors being Pākehā. “Most of them were members of the Patu Squad.”

As he had many times before, Harawira planned to defend himself in court. He’d had University of Auckland law lecturers Jane Kelsey and David Williams to rely on for advice, but this time he wasn’t sure it going to be enough.

“The day before my court date, I’m sitting out the back in the cells thinking ‘jeez, what am I gonna do?’ Then the brain wave came to me. Bishop Desmond Tutu had been invited over by the Anglican church to come and do a speaking tour. Interest was still very high in apartheid South Africa. My mum knew George and Jocelyn Armstrong, who were part of the organisation that brought him over.

“So I rang my mum and said look, I want Bishop Tutu as a witness. She said, ‘He wasn’t there!’. I said, ‘that doesn’t matter! I want him for my witness’. So she said ‘OK when is it?’ And I said ‘Tomorrow! I’m gonna need him by about 10.30.’”

The next day Harawira and 10 others prepared to stand trial.

When the time came for him to give his defence, his star witness wasn’t there. “I read my statement. I’d come to the very end and I was dragging it out. I didn’t want to get out of the dock ‘cos I knew it hadn’t been enough to get me off. Then the door burst open, and someone looked at me with a big smile and just nodded and I knew then. So I asked the judge: ‘Can you please call my witness?’”

Harawira still laughs at the memory of the stunned faces of the judge, prosecution and jury as as the now-Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in his signature dark suit and purple cleric’s shirt, walked into the courtroom.

“And then I’m thinking, ‘What the fuck, now what do I do?’

“So he takes the stand and I go, ‘Could you please tell the court your name?’ And then I said, ‘Can you please tell the court your address?’ And he gave an address in Soweto. Instantly, if the room wasn’t already charged, everyone was completely wide-eyed now.

“And then I said, ‘Can you please explain to the court what apartheid is?’. And away he went. He must have spoken for 20 minutes. It was absolutely stunning. You could have heard a pin drop.”

He says that after Tutu had finished, neither he nor the prosecution could think of any more questions.

“As Bishop Tutu stepped out of the dock, all 11 defendants, we all stood up. Then our lawyers stood up, then the public, the screws from Mount Eden, the police stood up, then the jury stood up. Half of them were in tears. If was one of those moments. I knew right then and there we were gonna get off.” He crows in delight at the memory.

The group were acquitted of all charges.

“It’s kind of hard to believe but it’s all true. Meeting Nelson Mandela himself and going to his tangi, that’s another story.”

We are here thanks to you. The Spinoff’s journalism is funded by its members – click here to learn more about how you can support us from as little as $1.

The Springbok Tour

A DigitalNZ Story by Hana McIntyre

A digitalNZ story by Hana McIntyre

The springbok tour of the 1980’s was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the tour has led New Zealand to find and express our identity as people and as nation.

Maori take a stand

A group of maori protesters stand together with helmets on as police with baton smarch behind them.

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

The beginning

This pamphlet was given out in the 1960's in an effort to have maori included in the tour.

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

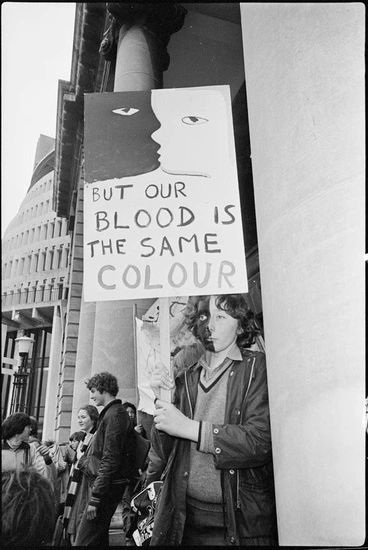

Together as a nation

All people of NZ came together to protest the tour, despite the debate on NZ racism, people of all backgrounds joined.

The tour was a useful tool as it helped to kick start the discussion of New Zealand's identity. For many decades New Zealand was in a limbo, we had the fundamentals of a culture events, people and objects all people could relate to. This is prominent in the source of the tour, rugby. Such a staple in ‘kiwi culture’, rugby is a thing everybody could enjoy no matter their race, age or gender. Rugby was a nationwide spot that the rest of the world knew as kiwi culture. However, this all changed when the announcement was made that the All Black would be taking am ‘all white’ team to play the springbok tour in South Africa.

Police resistance

Police and protesters in 1981

Children joined the fight

The tour did not only see adults who fought and protested, but it also saw young children protesting with their familie.

NZ Police 1981

Police where given 'night sticks' to keep protesters under control.

A nation always slightly confused about where the line of culture stood between Maori natives and the pakeha. This was an event that would change the way Maori people saw themselves and their culture within New Zealand's culture. People started to stand against the tour, peaceful marches where organized, rallies with children were held. People even boycotted games in an effort to bring awareness to the fact that an ‘all white’ team was unacceptable in a country where its native people would not be included in such a prominent activity that defined the nations sporting culture.

The riot squad posing for a picture in 1981. They where a step up for NZ police and a shock for NZ people.

Peaceful protesters fight against the Springbok tour and for the recognition of NZ's own faults.

The uncle of the of the captain of the NZ Maori team stood with the NZ Police in napier in 1981

Alexander Turnbull Library

Maori and Pacifica people started to express their identities more, “people started to realize you can’t protest against racism 6,000 miles away when it’s right here in your country” - John Minto This quote from John Minto clearly sums up the thoughts of many people at the time. How are we as a country supposed to find a collective identity if we cannot even see the own blatant racism that happens daily in New Zealand.

The New Zealand Police force are not known to be aggressive or violent. However, the springbok tour bought out the worst in the Police of New Zealand. On the night of the 21st of July 1981 Police brought down their ‘nightsticks’ onto a crowd protester’s who refused to ‘halt’, leaving many people with injuries. This is a prominent event within the Springbok tour. However, New Zealand does not let this define our police nor do we let it impact our culture in a manner where we lost all of the good relations between police and the New Zealand public. This however did tend to complicate the traditional depictions of kiwi culture, as we now had to reinvent the culture of NZ Police.

Public opinions

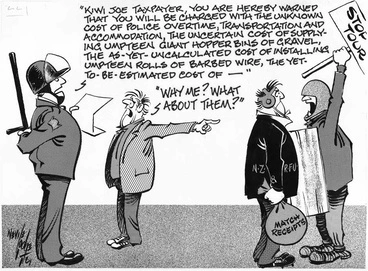

The tour effected everyone, the people who had a voice in society often used it in many ways this time a comic was drawn

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

![[Springbok Tour - Auckland street protest] Image: [Springbok Tour - Auckland street protest]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2Fd3085a739ec91232075a008722345e591fec81aa%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

Police vs Civilians

The tour of 1981 hindered civilians relations with NZ Police.

Police force

Police men and women get ready to face another encounter with protesters.

The tour tells us many things about how kiwis expressed their identities in the past. New Zealand has never been a violent country, new Zealanders have tended to express and convey their feeling through actions and speech. This is a part of kiwi identity in itself, we don’t identify as aggressive people or a nation who is an aggressive world party. This alone reinforces the idea of traditional ‘Kiwi Culture’. We are known as a people of fierce warriors but also known as a nation of respect and understanding.

Springbok Tour protest programme

School children protesting, 1981 Springbok tour

Furthermore, this event deepened our Maori populations identity within New Zealand. The tour made many people realize how poorly our own native people has been treated within our society. This was a catalyst for the change that we see today. Over the past thirty years New Zealand’s identity has become much more inclusive of Maori and all their traditional customs. Maori have become a large part of Kiwi identity and a larger part of ‘kiwi culture’. While the tour was a confusing time for many New Zealanders its consequence of the highlighting of Maori injustice helped to confirm what we see now as ‘traditional kiwi culture’.

New Zealand has always been a proud country, we like to think that we have always had each other's backs and continue to do so even through the toughest of times. The springbok tour was a major exception to this belief. However, this tour ended up adding value and lessons to which became some of New Zealand's most important values and morals. These have now become what we call ‘Kiwi culture’.

Peaceful Protest 1981

The people of New Zealand banded together for peaceful protests against the tour in Wellington 1981

Bibliography

References:

M. (2014, August 5). 1981 Springbok tour. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/1981-springbok-tour

T. (2006, July 16). Springbok Tour Protests 'Good For Maori'. Retrieved from http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO0607/S00145.htm

M. (2018, July 20). Police baton anti-tour protesters outside Parliament. Retrieved from https://nzhistory.govt.nz/police-baton-anti-springbok-tour-protestors-near-parliamentv

Listener, T. (2016, November 21). Inside the 1981 Springbok tour. Retrieved from https://www.noted.co.nz/archive/listener-nz-2011/inside-the-1981-springbok-tour/

Wellington City Libraries. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.wcl.govt.nz/heritage/tour.html

Roughan, J. (2017, August 25). NZ memories: Protests during the Springboks tour. Retrieved from https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10830511

http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/collection/object/am_library-ephemera-11756

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22905580?search%5Bi%5D%5Bcollection%5D=Dominion+post+%28Newspaper%29%3A+Photographic+negatives+and+prints+of+the+Evening+Post+and+Dominion+newspapers&search%5Bi%5D%5Bprimary_collection%5D=TAPUHI&search%5Bi%5D%5Bsubject%5D=Police&search%5Bpath%5D=items

Help us improve DigitalNZ

Do our short survey and let us know how we're doing.

Curating the 1981 Springbok tour

Aug 15, 2021

By Ian Brailsford

The fortieth anniversary of the 1981 Springbok tour has prompted several New Zealand museums, galleries, and libraries to organise commemorative displays, public talks, and film screenings to mark the event and the University of Auckland’s Special Collections is no exception.

Initial searches within our published and archival collections revealed active collecting by the General Library in its ‘vertical file’ of ephemera on the topic of sporting contacts with South Africa from the early 1960s onwards. Printed materials from groups such as the National Anti-Apartheid Committee, CARE (Citizens’ Association for Racial Equality) and HART (Halt All Racist Tours) had been preserved in the vertical file under the heading ‘Race relations’. For example, we located this 1965 CARE pamphlet opposing that year’s Springbok tour to New Zealand in addition to many items chronicling opposition to the 1970 and 1976 All Blacks tours to South Africa. We lacked, however, historic materials documenting either support for the tours or arguing that sport and politics should be kept at arm’s length. In effect, a Springbok display meant an ‘opposition to the tour’ display.

1965 CARE pamphlet, General ephemera collection, MSS & Archives 2015/23, Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

With only three display cases to work with, however, we decided that although the 1981 tour was part of a longer history of anti-apartheid organising in New Zealand we would focus on the autumn, winter, and early spring of 1981.

With our extensive holdings relating to the University of Auckland we expected to find items that would speak to a student audience. In our university photography collection, we found a black and white print of two students, Sara Noble and Kevin Hague, in the Student Union ‘Quad’ staging a hunger strike against the tour in a ‘Bantu hut’ constructed of wood and corrugated iron. We located the photo in the New Zealand Herald which ran with the story of the protest on 29 April and included this in the display. [1]

The Springbok tour dominated the pages of the student association weekly newspaper Craccum during 1981. The Craccum issue following the final test match at Eden Park on 12 September, for instance, featured a four-page photo montage ‘Tour souvenir lift out’. [2]

However, the one time a vote was held on campus among the student body relating to the tour, in August 1981, a small majority of students (1740 to 1735) voted against a motion proposing that student association funds be allocated to pay for anti-tour activities. [3] While the tour is sometimes seen as a generational divide, the fact that a significant number of University of Auckland students opposed funding anti-tour ventures indicates it was more nuanced than this.

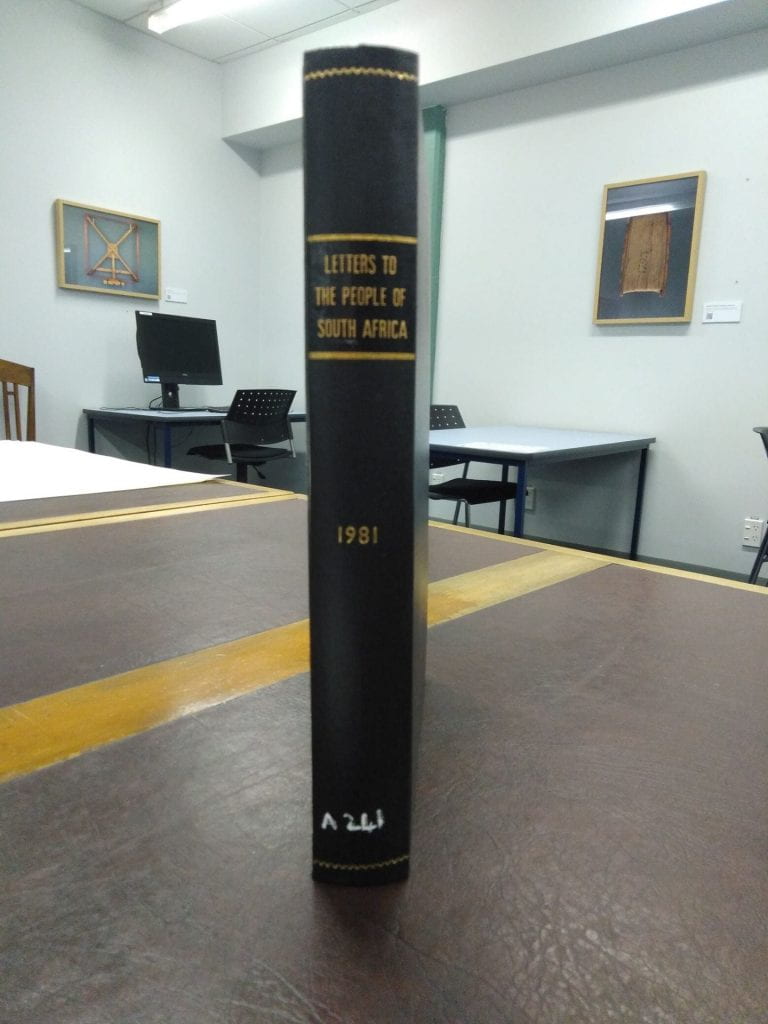

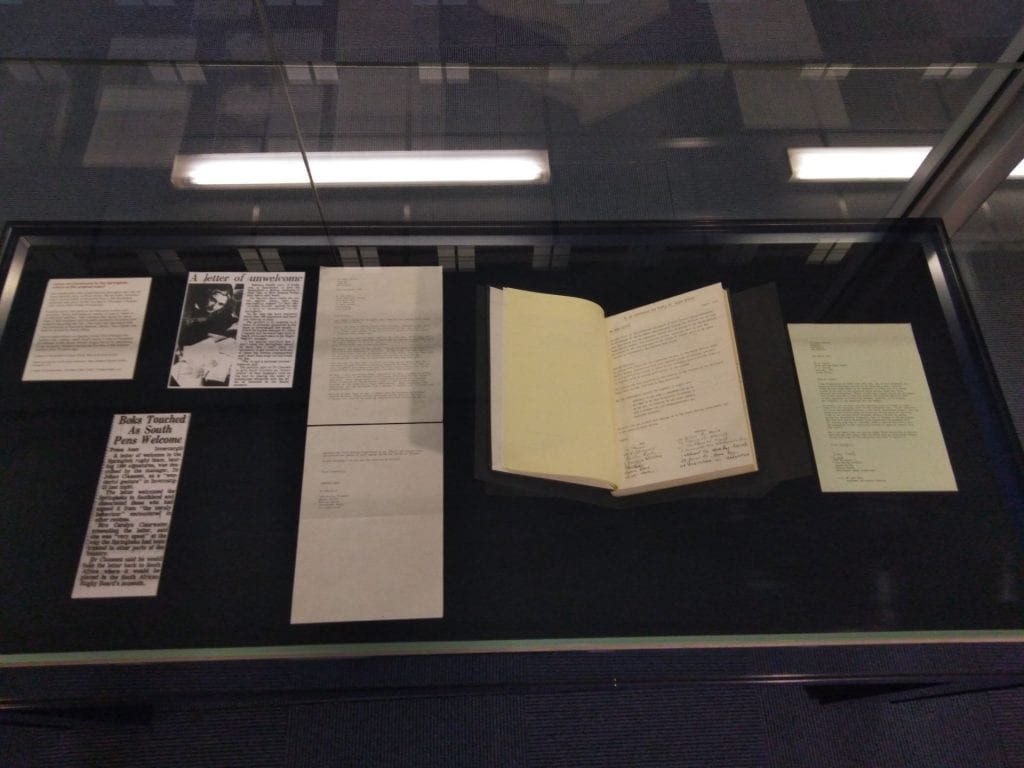

The centrepiece of our display is an archival item, the story of which teases out some of the complexities surrounding the tour. The General Library in February 1982 received a copy of an anti-tour ‘letter of unwelcome’ petition for depositing in the archives. It’s a hardbound copy of the petition catalogued as MSS & Archives A-241, with the snappy title ‘Letters to the people of South Africa from citizens of Auckland and citizens of Dunedin to the South African Rugby Board Museum’.

Bound copy anti-tour petition, MSS & Archives A-213, Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

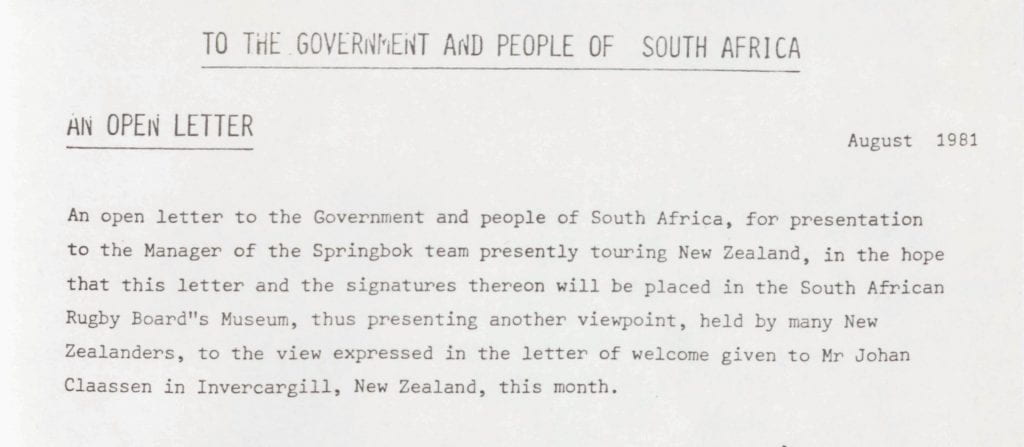

The origin of the petition was a letter of welcome to the Springbok touring party when they arrived in Invercargill for a match against Southland on Saturday 8 August. Over 1,300 Southland residents had signed the letter and Springbok tour manger, Dr Johan Claassen, promised to preserve it in the Rugby Board’s museum when he returned home to South Africa. The New Zealand Herald quoted Southland resident Carolyn Springwater, who handed over the letter to the team, as being ‘very upset’ by the way the Springbok tourists had been treated in other parts of New Zealand. [4] Here was archival evidence of New Zealanders who supported the tour but one that had (most likely) gone offshore.

Our ‘letter of unwelcome’ petition was a direct response to the Southland welcome letter. The petition was started in mid-August by Remuera mother and daughter Jenny and Rebecca Hanify, as a ‘personal protest’ against the tour. They wanted to create a lasting memento to sit alongside the Southland letter in the Rugby Board museum. In total more than 3,500 Auckland and Dunedin residents signed in one month. Two of the first signatures were the former Auckland Mayor Dove-Myer Robinson and incumbent Colin Kay. Rebecca Hanify was quoted in the Auckland Star saying that she was against apartheid, but she didn’t, ‘think it’s necessary to get involved with any of these big protest organizations and I don’t want to go out and break the law’. [5]

Opening text of anti-tour petition, MSS & Archives A-213, Special Collections, University of Auckland Libraries and Learning Services.

The original copy of the petition was mailed to South Africa in September 1981. A further letter in our collection from March 1982 indicates that it reached South Africa, but the South African Rugby Board refused to accept it. If the original is lost, then our copy of the petition is the only one left.

Tantalisingly, the Springbok Experience Rugby Museum in Cape Town closed in 2019, so tracking down whatever happened to both letters – welcome from Southland and unwelcome from Auckland and Dunedin – is proving difficult. We have the hope that displaying the item, writing about it on the library’s website and on this blog might trigger someone’s memory. We would also like to hear from the Hanify family so they can revisit their contribution to our collective memories of the 1981 Springbok tour.

Display case featuring petition and associated items.

[1] ‘Hunger as tour protest’, New Zealand Herald, 29 April 1981, p.16.

[2] ‘Tour souvenir liftout’, Craccum, Vol. 55, No. 21, 15 September 1981, pp.11-14.

[3] ‘No one wins’, Craccum, Vol. 55, No. 20, 8 September 1981, p.4.

[4] ‘Boks touched as south pens welcome’, New Zealand Herald, 8 August 1981, p.3.

[5] ‘A letter of unwelcome’, Auckland Star, 9 September 1981, p.3

Remembering the 1981 Springboks Tour

For the 40th anniversary of the 1981 Springbok Tour, we talked to two Wellington residents who remember those turbulent times.

During the winter of 1981, violent clashes between rugby supporters, protesters and the police erupted all over Aotearoa in one of our country’s most tumultuous periods. The Springbok rugby tour was a tumultuous time for the nation with many protesting the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home.

Our Digital Communicator, Tom Etuata and our Senior Curator (Taonga Māori), Lawrence Wharerau, interviewed Liz Roberts and Anne Bogle, who both shared their stories of the protests.

The Merata Mita Estate permitted us to use the Wellington footage from PATU! (1983) – the powerful documentary directed by Merata Mita which shows the harrowing events of the 1981 Springbok Tour. Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision meticulously restored and preserved the original documentary for the 40th anniversary. With their approval, we were able to use their newly restored and remastered version for these videos.

Liz Roberts lived on Te Wharepōuri Street in Berhampore, close to Athletic Park, and recalls the events of the 2nd Test on August 29th, 1981, where she saw protesters clash with Police on her street.

Anne Bogle was a young Victoria University student studying Law and History in 1981 – and attended a number of Anti-Tour protests in Wellington – she took part in the protest group that blocked the Wellington Motorway on July 25th and the infamous Molesworth Street incident a few days later on July 29th. The protester helmet she used during the anti-tour demonstrations is currently displayed at Wellington Museum.

Thank you to the Merata Mita Estate for their permission to use parts of the film and also to Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision for their great mahi on the preservation and restoration of this important piece of film taonga.

Also thank you to Anne Bogle and Liz Roberts for sharing their stories.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Recent Posts

- Mātanga Pakihi | Retail Specialist Wellington Museum

- Kaiārahi Wheako Manuhiri | Manager Visitor Experience

- 14 Unique Things to Do in Wellington

- Wellington Museum continues to welcome visitors after seismic assessment

- Safe Spaces Statement

Recent Comments

- October 2023

- February 2023

- October 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2020

- August 2018

- October 2017

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Job Vacancy

- Uncategorized

- Entries feed

- Comments feed

- WordPress.org

1981 Springbok Tour: Nelson Mandela's salute to NZ protest movement

Share this article

Reminder, this is a Premium article and requires a subscription to read.

People were left bloodied and bruised, friendships ended and civil unrest hammered our nation during the Springboks 1981 tour. But 40 years on, Neil Reid reports the sporting event which divided New Zealand had a positive legacy globally.

When the ground announcement was made to cancel the Springboks' clash against Waikato a fiery chorus of "We want rugby" boomed around Hamilton's Rugby Park.

The screams of anger only amplified as the 300 spectators who had earlier stormed the ground were led off the field and into a barrage of full beer cans, punches and kicks from incensed rugby fans.

More than 11,600km away, the noise created by inmates on Robben Island – including ANC activist and future South African president Nelson Mandela – on hearing of the match's abandonment was also deafening.

But the noise they made – including hitting the doors of their cells with whatever objects were at hand – wasn't out of anger.

Instead, it was out of joy that the sporting team which was viewed by many around the world as the ultimate symbol of white rule in South Africa had been tackled by everyday Kiwis.

The moment was shared Mandela during his presidential visit to New Zealand in 1995, when he told those who had been at the frontline of anti-tour protests that when news of the events in Hamilton reached the stark prison of Robben Island it was "like the sun came out".

Among the gathering was long-time activist and Halt All Racist Tours (HART) leader John Minto who had suffered numerous cuts and bruises while protesting during the 1981 tour.

He said that comment had made any physical pain he endured on the frontline of protests during the tour worthwhile.

"Nelson Mandela said when he was here that it was like 'the sun came out' when he heard this game had been cancelled . . . that people on the other side of the world had used civil disobedience to cancel a game," he told the New Zealand Herald.

"That was really reinforcing for me . . . the impact was enormous."

During his meeting with leaders of the anti-tour leaders 14 years on from the divisive sporting event, Mandela also stated: "You elected to brave the batons and pronounce that New Zealand could not be free when other human beings were being subjected to a legalised and cruel system of racial domination."

New Zealand and successive governments had gone on to "stand tall as one of the most committed supporters of the anti-apartheid cause".

Hitting South Africa where it hurt the most

Rugby has provided both the biggest bond and rivalry between New Zealand and South Africa.

The two nations had done battle on the rugby field since 1921. Staggeringly, it wasn't until 1956 that the All Blacks finally secured a series win over the Springboks.

The biggest strike New Zealand could make against South Africa's racist apartheid regime was via cutting all rugby contacts with the nation.

In the year leading up to the tour that was a line which was heavily pushed by an ever-growing anti-tour movement; which included opposition MPs, human rights campaigners and everyday Kiwis.

But in the face of increasing protests, the New Zealand Rugby Union controversially pushed on by issuing an invitation to their South African counterparts in late 1980 for the Springboks to tour the following year.

Previous tours by the Springboks to the UK and Ireland in 1969-70 and to Australia in 1971 had led to huge protests in those respective nations. When it became clear the 1981 tour would go ahead, protest leaders here vowed to do all they could to ensure the Boks would be considered too unpalatable to compete against until apartheid was scrapped.

That also required everyday white South Africans who were obsessed by the Springboks to lobby for change; something which Patu Squad protest leader and futuer MP Hone Harawira said was achieved by the level of protests in New Zealand – including two matches being cancelled due to security issues.

"Rugby was an absolute religious force in South Africa," he said. "Just after God, or it might have been right up alongside God, for white South Africans was the Springboks.

"And they would choose a Springbok jersey over a selection to go Oxford University. That is how important rugby was to them."

Minto said HART was proudly part of an international campaign "to isolate South Africa" with its actions protesting the tour.

One of the motivations of the local actions – which culminated with the violent clashes outside Eden Park on the day of the third and final test – was for it be "very hard for the Springboks to leave South Africa after our protests".

But while on the frontline of protests around the country – where he had pain inflicted on him by both police batons and the fists of rugby fans – he never imagined the magnitude the stance he and his colleagues would have in South Africa.

"We knew it would be significant, but it wasn't until I went to South Africa for the first time in 2009 that it really hit home to me," he said.

"I had black, white and coloured South Africans talking to me about this and talking about the huge watershed moment for South Africa after the game in Hamilton had been cancelled.

"It shouldn't be surprising because rugby links with South Africa were the most important thing for white South Africans and in terms of rugby here, the most important link here New Zealand had to the rugby world."

Springbok captain: "Good" came out of tour violence

The Springboks never expected to face the wave of protests and hatred that were directed their way while in New Zealand.

Naively, they thought as a sports team they wouldn't be brought into the highly-charged political debate over the repugnant apartheid regime that ruled their homeland.

No sports team has ever operated under the conditions that face them; they were guarded around the clock by police, it was deemed unsafe for them travel in small groups with team issue gear on, and on the eve of the final two tests of the tour they slept in function rooms at Athletic Park and Eden Park to avoid contact with protestors.

Despite the turmoil, the side's captain Wynand Claassen doesn't regret the decision to go on tour as the "impact on South Africa was as much positive as it was negative in New Zealand".

"The system slowly started to turn after that. It was the start of the final change, because after that South Africa was totally isolated in terms of sport," he said in the book, Springbok – The Official Opus.

"If we look for positives, it was the 1981 tour that encouraged change. It wasn't great but then you can't deny the good that came out of it."

And the tourist's only non-white player, Errol Tobias, said the determination adopted by protestors – including those who continued to fight the tour despite being left bloodied and bruised - ultimately proved to be a "catalyst" for South African law makers to start a reformation process.

But it did take time. Apartheid wasn't fully revoked until 1994.

"Today, the tour and the resistance it was met with are seen as the most important catalyst in the struggle against apartheid in South African rugby," Tobias wrote in his autobiography, Pure Gold.

"Fundamental change was non-negotiable, although it only followed a decade later."

Forty years on, Harawira said there was no doubt the anti-tour movement in New Zealand had played its part in getting rid of apartheid.

But he said in reality protestors here had been playing a support role for brave human rights activists of all colour who risked their lives in their native South Africa to fight apartheid.

"It took a lot more action in South Africa, and not here, and more people dying before it became clear to the authorities that, 'Do we even have enough white people if this goes to war'," Harawira said.

"In the end the decision was entirely South Africa's. But we had a role to play, as did Cuba who supported black South Africans by supplying them with money and arms, and other countries like Libya."

"It changed New Zealand forever"

When the All Blacks lined up for three test series against the Springboks two prominent names were missing from the team.

Captain Graham Mourie and 102-match veteran Bruce Robertson had made themselves unavailable for the clashes on moral grounds.

Mourie went public with his stand eight months before the Springboks flew into New Zealand; basing it on what happened off the field on previous Bok tours, his own research into apartheid and fears of what could eventuate here.

Mourie wasn't engrossed in the action on the field during the tour. Neither did he make his presence felt at protests.

Instead, he watched on from afar as his worst fears were played out around New Zealand.

The 1981 tour became synonymous with violent clashes between protestors and police wearing riot gear and grandstands at club grounds targeted by arson attacks.

Passive protest actions included teachers refusing to coach rugby, while thousands of parents stopped their children from playing the sport.

"What happened [in Britain and Australia] was to a degree a forerunner of what was to happen here," Mourie said. "We managed to top them pretty easily . . ."

"Could you have seen it [the fierce protests] coming? Probably not to the degree that it was. But it [anti-tour anger] was certainly part of the discussions I had with Ian Fraser and a couple of other people . . . what they thought the outcome would be."

Forty years on, Mourie said the Springbok tour was an event which he now viewed as a nation-changing event.

"If you want to look at events that evolved New Zealand . . . things like [the Springbok tour] changed how we viewed the world. In my mind, it certainly changed New Zealand forever.

"We suddenly had police out there in riot gear and we had a change with ways we dealt with issues forever."

Minto also said the tour changed the mindset of our nation forever – and for the good.

While the focus of protests had been on apartheid's mistreatment of non-white South Africans, it had also shone a spotlight on New Zealand's own racial issues.

"New Zealand is a very different place to what it was then in all sorts of ways," Minto said.

"The lasting legacy of the tour has been on race relations here. It pushed the debate about Maori and pushed New Zealanders into a bi-cultural frame of mind.

"I think that has had a huge positive impact."

Harawira also heralded positives to New Zealand's own race relations following the tour.

He said it wasn't just the plight of non-white non-white South Africans that motivated many protestors to take to the streets before and during the tour.

Protests had also provided the chance for Maori and Pasifika a platform to air their own grievances on how they felt mistreated.

"We got the apartheid thing, we understood that," Harawira said. "We were pissed off like everybody else that the New Zealand Rugby Union didn't give a s***.

"But there was also that whole racism in New Zealand. It was a double-edged sword for us. We were fighting apartheid in South Africa and striking a blow against racism in New Zealand as well."

Latest from Kahu

Two Goldies and a Hotere sold at Auckland art auction

The two Charles Goldie works sold under the hammer will stay in NZ.

Seymour and Peters should be ashamed denigrating Efeso Collins’ legacy

'I’m inspired every single day by working in the natural world'

Crown ordered to pay Foxton hapū compensation

Kids missing school to feed families

Stop the Tour Novel Study and Discussion Questions | The 1981 Springbok Tour

Click here to see a preview of this resource.

Description

- Reading comprehension questions,

- Discussion questions for oral language development in the classroom, designed to be used with pairs or small groups of students

- Weblinks and QR codes for students to find out more about the content discussed

- Six to eight creative activity choices (including digital and non-digital options)

THIS RESOURCE, AND OUR FULL RESOURCE RANGE IS ALSO AVAILABLE IN OUR TOP TEACHING TASKS MEMBERSHIP. FIND OUT MORE HERE.

You may also like….

Dawn Raid Novel Study and Discussion Questions

New Zealand Protests Reading and History Bundle

Kensuke’s Kingdom Novel Study and Discussion Questions

Gold!: Otago, 1862 Novel Study and Discussion Questions

Related products.

Digital Non-Fiction Reading Comprehension for Google Classroom

Pacific Islands Scavenger Hunt Puzzles BUNDLE

Reading Comprehension Passages and Questions Mega Bundle

Video Games Reading Comprehension Passages and Questions BUNDLE

How it works

Classroom sessions, many answers, springbok rugby tour 1981.

Where can I find information about the Springbok Rugby Tour of 1981?

(Years 11-13)

Image: Anti-Springbok tour demonstration, Willis St, Wellington by Evening Post. Collection: Alexander Turnbull Library.

Entry last updated: 18/08/23

Introduction

In 1981 the South African rugby team, the Springboks came to tour New Zealand. They had toured before, but the South African apartheid system was causing an increasing public outcry in New Zealand. Things came to a head in 1981, with New Zealanders fiercely divided over whether the Springbok tour should go ahead. There were numerous protests at rugby games around the country and some violent encounters between the pro-tour and anti-tour movements.

Before the tour

The South African Springboks and the All Black rugby teams had toured New Zealand and South Africa before 1981. Try these sites for information about the background of this particular tour and why it was controversial.

Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Te Ara is an excellent starting point for all questions about New Zealand Aotearoa. If we scroll down to the bottom of the page we can see that the website belongs to the Ministry for Culture & Heritage, so the information is well-researched and reliable.

Use the keywords 'Springbok rugby tour' to search.

There is not one specific entry for the 1981 Springbok tour, but there is information about it in several entries such as Rugby and South Africa and Politics of sport .

These entries give a summary or timeline of events leading up to the tour.

Tips: Search words, or keywords, are the most important words in our question. Usually it’s better to leave out small words like ‘the’, ‘a’ and ‘of’ and just choose the main ones, e.g. 'Springbok rugby tour' We can always change our keywords or add more if we need to.

Supporters and protesters

Have a look at these sites to find out about opinions on both sides of the controversy.

DigitalNZ brings together lots of digitised New Zealand content and culture, and is a good place to look for information about the Springbok Rugby tour.

Enter your keywords eg 'Springbok Tour 1981' or ‘Springbok Rugby'.

The results are grouped by the type of information, like images, audio, videos, newspapers, articles and research papers_._

Tips: Websites that have .org or .net in the address can have good information, but you need to assess how reliable it is. Check the About us link on the website, if you can find one. That can tell you what the organisation’s mission and values are.

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Funded by the Ministry for Culture and Heritage, Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision is New Zealand’s audio-visual archive. Their collection includes film and television, radio and sound recordings, props, posters and more from over 120 years of New Zealand’s history.

Select Catalogue.

Enter the keywords '1981 Springbok tour' and make sure to select Available Online.

Listen to Springbok tour 1981 - compilation .

This is a collection of 13 cuts of radio coverage of the protest surrounding the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand.

Radio New Zealand

This is New Zealand's public radio service on New Zealand news, current affairs, Pacific, Te Ao Māori, sport, business including opinions and analysis.

Go to the tab called Topics at the top of the page, then scroll down the page to Collections.

Find the collection called The 1981 Springbok rugby tour which is all about the game and the protest actions.

Tips: Websites that have .com or .co in the address can have good information, but you need to assess how reliable it is. Check the About us link on the website, if you can find one. That can tell you what the company’s mission and values are.

Museum of New Zealand - Te Papa Tongarewa

Te Papa is New Zealand's National Museum and it houses collections and exhibitions about 20th Century history and culture. Te Papa has a collection of images, posters, objects and videos from the 1981 Springbok rugby tour.

Go to Discover the collections and then select the Collections Online page.

Search for '1981 Springbok'.

Go to Springbok Rugby Tour 1981 and find the video Rugby ball and John Minto .

Tips: We like sites that are from government or other reputable organisations, because we can trust the information. You can sometimes tell these sites by their web address – they might have .gov or .edu in their address – or by looking at their About us page.

The Aotearoa History Show

This video podcast from Radio New Zealand tells the story of Aotearoa New Zealand from when the land was formed to today.

Look through the episodes for 13: Decades of Change .

You can either listen to the podcast or watch it as a video.

Look under the video for the topics that the podcast covers.

The New Zealand History Collection (BWB)

The New Zealand History Collection is also a part of the EPIC databases. Here you will find a collection of ebooks on New Zealand history and biography titles from Bridget Williams Books. It has a book about what happened during the protests in Auckland.

Find the title When the Tour Came to Auckland and select Read Now.

Move through the chapters by using the arrows at the top of the page.

Or select the three lines to go back to the Contents.

Tips: To get to the EPIC resources you will need a password from your school librarian first. Or you can chat with one of our AnyQuestions librarians between 1 and 6pm Monday to Friday and they will help you online. Some EPIC databases may also be available through your public library.

After the tour

Try these websites to understand the impact the tour had on New Zealand society.

NZHistory is another reliable website from the Ministry of Culture and Heritage. It has sections on the culture, politics, people and history of New Zealand.

Select the section on Culture and Society.

Look under Sport to find 1981 Springbok tour .

Read through the pages to find out about the protest and the impact it had on the people and politics of New Zealand and South Africa.

New Zealand Geographic Archive

Another EPIC resource, this site has got some great pictures.

Search using the keywords 'springbok tour' to find articles, like Tainted Games .

NZ On Screen

NZ On Screen is the online showcase of New Zealand television, film and music video. All content is free to view. There are several films on the effects of the tour.

Enter the keywords ‘Springbok Tour'.

Select the Collection called The Springbok Tour - 35 Years On .

Tips: Websites that have .com or .co in the address can have good information, but you need to assess how reliable it is. Check the About us link on the website, if you can find one. That can tell you what the company’s mission and values are.

Books and DVDs

There are books that have been written on the Springbok rugby tour of 1981 - check out your local public or school library to see what they have.

Here are some recommended titles:

Storm out of Africa: the 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand by Richard Shears, Isobelle Gidley

By batons and barbed wire by Thomas Oliver Newnham

Sitting on the fence: the diary of Martin Daly, Christchurch, 1981 by Bill Nagelkerke

The 1981 Springbok Tour protests by Stephen Penny.

SCIS no: 1839526

Topics covered

Related content.

Human rights

Where can I find information about human rights?

Where can I find information about the first and second Boer Wars?

Springbok Tour 1981

Discover resources related to the Springbok Tour 1981.

Discover resources related to protests in New Zealand.

History (New Zealand)

Where can I find information about New Zealand history?

Have you booked a classroom session with us for this time?

If you have not pre-booked a session at this time, please email [email protected] We will then get back in touch with you confirming your booking.

College tour season is about to kick off. Here are 10 tips from college tour guides to have a successful campus visit.

- As spring starts, colleges nationwide will welcome parents and students to tour their campuses.

- College tour guides want people to arrive on time, ask the right questions, and have fun.

- They also recommend students take the tours on their own, without their parents.

Spring break is right around the corner, and for many high-school students and their parents, that means many will be hitting the road to tour colleges around the country.

To make the most of your visit, Business Insider spoke with college students and tour guides. They know the campuses like the backs of their hands, and they know how to walk backward.

Here are the dos and don'ts of college tours from student guides .

1. Get there with no time to spare, but don't be late.

You won't get points for arriving early, so try to arrive on time. But if you do happen to arrive late , there's no need to worry.

"If something comes up and you are late, ask your guide what you missed once the tour finishes," Skyler Kawecki-Muonio, a senior at Sarah Lawrence College in New York, told BI. "They will happily fill you in."

2. Dress to impress, but don't sacrifice comfort.

It's important to look nice, but you don't have to don a jacket and tie. Tour-goers should put their best foot forward with a sturdy pair of walking shoes , and don't forget to dress for the weather.

"At Fairleigh Dickinson, tours go out rain or shine, so make sure to wear clothes that will keep you warm," Emily Bone, a junior at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey, said .

3. Don't forget to sign in, but skip the résumé .

Most schools have a check-in desk where you'll receive a campus map and other literature. But don't bother furnishing schools with your portfolio.

"Students can leave their résumés at home," Henry Millar, a senior at the College of William & Mary in Virginia, said. "Tour guides generally do not have any sway in the admissions process whatsoever, so feel free to save the paper."

4. Pay attention on the tour, but do it solo if possible.

Some schools offer to let parents and kids take separate tours, which has advantages.

"Get excited about your child's potential future in college, but give them some space to see what they think of that school on their own," Nathan Weisbrod, a junior at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, told BI.

Related stories

Students can comfortably ask questions without a parent present and compare notes afterward .

5. Ask all your questions, but avoid personal interrogations.

This is the time to inquire about any aspect of campus life , and don't feel shy about speaking up.

"Tour guides love getting questions because it allows us to cater the tour, especially in small groups, toward the needs and interests of the families on that specific tour," Halle Spataro, a senior at Bucknell University, said.

But some topics are off-limits, so don't ask your tour guide about their SAT scores , ACT scores , or what they wrote about in their essay .

6. Speak up, but let the student take the lead.

Parents may be tempted to raise their hands again and again, but this tour is about the student, so there should be space to let them shine.

"Try to take the back seat — or the passenger seat — but refrain from driving all of your child's interactions," Julian Jacklin, a junior at Reed College in Oregon, said. "Students who feel they can own that experience usually ask the most questions and engage with the tour more."

7. Say thanks, but don't leave with questions unanswered.

Maybe your guide didn't hear you, or your kid was reluctant to speak up. You can still get the information you want before leaving.

"There's a lot of information students are getting that day and a lot of excitement with being in a new place, which can make people forget to ask certain questions," Lorenzo Mars, a junior at Pepperdine University in California, said.

Therefore, get your tour guide's email address so that you can follow up .

8. You may know exactly what school is right but keep an open mind.

Don't be surprised if a city-living kid is suddenly intrigued by a small-town setting.

"The college search and college experience are all about getting to know yourself better and growing, so on a tour, students have to trust themselves and their judgment of the 'world' they've just stepped into," Thomas Elias, a senior at the University of Scranton in Pennsylvania, said .

9. Take in as much as possible, but remember to have fun.

Sure, preparing for the next four years can be scary and stressful. But it's also an exciting milestone, so enjoy the ride.

"These tours serve as great opportunities to learn more about colleges — along with their cities, culture, and people," Connor Gee, a sophomore at the University of Mississippi, said. "Have fun with it!"

10. Weigh the pros and cons of the school, but don't stop there.

Your tour may be over, but you can still learn other ways to immerse yourself in college life .

"See if the school offers additional experiences, like eating in the cafeteria or attending a class," Emily Balda, a senior at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, said. "Consider it 'food for thought.'"

Watch: What new Citadel military college "knobs" go through on day one at the controversial school

- Main content

IMAGES

COMMENTS

1981 Springbok tour Page 1 - Introduction. A country divided. For 56 days in July, August and September 1981, New Zealanders were divided against each other in the largest civil disturbance seen since the 1951 waterfront dispute. More than 150,000 people took part in over 200 demonstrations in 28 centres, and 1500 were charged with offences ...

Police officers guarding a barbed wire perimeter around Eden Park near Kingsland railway station.. The 1981 South African rugby tour (known in New Zealand as the Springbok Tour, and in South Africa as the Rebel Tour) polarised opinions and inspired widespread protests across New Zealand.The controversy also extended to the United States, where the South African rugby team continued their tour ...

The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home. On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa's ...

On August 15 1981, Christchurch was a city on edge. The first test match of the 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour of New Zealand (Tour) was to be played at Lancaster Park. Anti-apartheid protesters prepared themselves for an uncertain day, donning protective clothing and making final preparations for the march to the rugby ground.

Check out RNZ's collection of audio about the 1981 Springbok Tour; Dr Sebastian Potgieter is a South African who moved to Dunedin to conduct a PhD on the Springboks tour. Back in 1981, the general public in South Africa wasn't too familiar with what was going on in New Zealand yet the Springbok tour of that year negatively affected the team's ability to play internationally, Dr Potgieter tells ...

For years, New Zealand spoke proudly of having 'the finest race relations in the world', however events that unfolded during the 1981 Springbok Tour challenged this statement - the claim was that Pakehas, while only too keen to fight apartheid in South Africa, were unwilling to confront the racism in New Zealand of which they are the beneficiaries.

Andrew Beyer remembers the protest against the Springbok tour of 1981 and Nelson Mandela's visit to New Zealand in 1995. It's about politics, apartheid, racism, boycotts, anti-springbok protests and a secret tour. A brief history of the 1981 Springbok tour that divided the nation.

When the Springboks arrived in Nelson on Thursday August 20, 1981 - they were met with strong protest and a city divided over the question of apartheid. There were clashes between pro-tour supporters, anti-tour protestors, and the police. There had already been demonstrations in Christchurch and the Timaru game had been cancelled.

Nicknamed the Day of Shame, July 22 saw the Springboks' opener against Poverty Bay. Three hundred protestors marched to Rugby Park in Gisborne via a nearby golf course and attempted to breach a ...

The Springbok Tour. The springbok tour of the 1980's was the largest civil disturbance New Zealand had seen in thirty years. The whole of New Zealand was divided over the tour, this division of the country lasted over fifty days. The Springbok tour was a real factor in the way New Zealand grew as a county. The outcomes that arose from the ...

The Springbok tour dominated the pages of the student association weekly newspaper Craccum during 1981. The Craccum issue following the final test match at Eden Park on 12 September, for instance, featured a four-page photo montage 'Tour souvenir lift out'.[2] However, the one time a vote was held on campus among the student body relating ...

Tension around the country grew as the Springbok Tour made its way around New Zealand. Here's a look back at one of the most controversial sporting tours eve...