The Brief Period, 200 Years Ago, When American Politics Was Full of “Good Feelings”

James Monroe’s 1817 goodwill tour kicked off a decade of party-less government – but he couldn’t stop the nation from dividing again

Erick Trickey

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/87/68874c05-8488-4650-84f8-0c64b2d11b69/independence_day_celebration_in_centre_square.jpg)

James Monroe rode into Boston Common astride a borrowed horse, wearing a blue coat, knee-buckled breeches and a Revolutionary triangular hat. A cheering crowd of 40,000 people greeted him.

But it wasn’t the 1770s, and the founding father was no longer young. It was July 1817, and the new nation was 41 years old. The clothing worn by the nation’s fifth president was now out of fashion. He wasn’t in Boston to drum up support for a new nation—he was there to keep it from falling apart.

Monroe, a Democratic-Republican, had won a landslide victory against the collapsing Federalist Party in the 1816 election. Now, he was touring the nation, ostensibly to visit military installations, but also in hopes of stirring up a patriotic outpouring that would bring about the end of political parties in the United States.

He wanted to heal the wounds of the War of 1812, hurry along the Federalist collapse, and bring about the party-less government George Washington had envisioned in his farewell address. And he succeeded, for a while. Monroe’s presidency marks the last time the United States didn’t have a two-party system.

Monroe swept into the presidency as an American war hero and a symbol of the young nation’s history. He’d joined the Continental Army in 1776, was wounded at the Battle of Trenton and survived the brutal winter of 1778 at Valley Forge. He was elected to the Virginia legislature, the Continental Congress, and the U.S. Senate. He served twice as an American diplomat in France and was governor of Virginia. In 1811, President James Madison named him secretary of state.

During the War of 1812, Monroe stepped up to rally the nation he’d helped form. In August 1814, the British captured Washington, D.C., and burned nearly all its public buildings, including the White House. Returning to the wrecked capital after a British retreat, the overwhelmed Madison, whose cerebral temperament left him ill-prepared to lead in wartime, handed Monroe a second title: acting secretary of war. He took charge of the war effort, reinforcing Washington and Baltimore, ordering Andrew Jackson to defend New Orleans, and convincing state governors to send more militiamen to the battle zones.

By the war’s end, the partisan conflict that had defined American politics for two decades was sputtering out. Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans, who believed in limited powers for the federal government, had held the presidency for 16 years, since Jefferson’s 1800 defeat of Federalist John Adams. But war had scrambled the parties’ old roles. Federalists in New England had largely opposed the War of 1812. Many gathered at the secret Hartford Convention of 1814-15 , where the most radical delegates called for New England to secede from the Union. Instead, the convention voted to send negotiators to Washington to demand changes in the Constitution, including limits on the president’s power to make war. But news of the war’s end reached Washington before the Federalist delegates did, leaving them looking like near-traitors who had schemed in secrecy.

Monroe won the 1816 election in a landslide and developed a plan to, in his words, “prevent the re-organization and revival of the federal party” and “exterminate all party divisions in our country.” His motives were mixed. Like Washington, he believed that political parties were unnecessary to good government, but he was also furious at the wartime Federalist secessionist movement. He froze out the Federalists, gave them no patronage, and didn’t even acknowledge them as members of a party. But publicly, Monroe made no partisan comments, instead appealing to all Americans on the basis of patriotism. “Discord does not belong to our system,” he declared in his inaugural address. “Harmony among Americans… will be the object of my constant and zealous attentions.”

Emulating Washington’s tours of the nation as president, Monroe set out on his first goodwill tour on June 1, 1817. He spent all summer touring the nation, traveling by steamboat and carriage and on horseback. Like politicians today, he shook hands with aging veterans and kissed little kids. He toured farms, hobnobbed with welcoming committees, and patiently endured endless speeches by local judges.

Boston was the biggest test of Monroe’s goodwill. Massachusetts was the nation’s citadel of Federalism, and it had voted for Monroe’s opponent, Rufus King, in 1816. But Boston seized the chance for reconciliation, greeting Monroe with boys clothed in mini-versions of Revolutionary attire and 2,000 girls in white dresses, decorated with either white or red roses, to symbolize the reconciliation of the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans.

The night of his victorious appearance on Boston Common, Monroe attended a dinner hosted by Massachusetts Governor John Brooks. To his surprise, other guests included John Adams, the Federalist ex-president, and Timothy Pickering, the former Federalist secretary of state who had recalled Monroe from his diplomatic post in Paris in 1796. “People now meet in the same room who would before scarcely pass the same street,” marveled Boston’s Chronicle and Patriot newspaper.

Boston swooned. On July 12, the Columbian Centinel, an ardent Federalist newspaper, published a headline , “Era of Good Feelings,” that would define Monroe’s presidency. “During the late Presidential Jubilee,” the story began, “many persons have met at festive boards, in pleasant converse, whom party politics had long severed.”

The origin of The Era of Good Feelings in the Columbian Centinel 12 July 1817! pic.twitter.com/7jET2BL3TH — James Monroe Museum (@JMonroeMuseum) July 12, 2017

Returning to Washington in September 1817, Monroe extended the good feelings into national policy. He convinced Congress to abolish all of the federal government’s internal taxes in the U.S., including property taxes—confident that customs tariffs and the sale of public land could fund the federal government. Yet he still paid off the nation’s $67 million war debt within two years. (Tariffs continued to pay for the federal government’s budget until the Civil War, when the federal government founded its department of internal revenue.) He supported Andrew Jackson’s 1819 invasion of Florida, then had John Quincy Adams negotiate a treaty with Spain that ceded Florida to the U.S. The Monroe administration built up the nation’s defenses and strengthened West Point into an elite military academy. Pioneers flooded westward. In his 1823 message to Congress, he articulated what came to be known as the Monroe Doctrine, warning European powers that any future attempt to colonize the Western Hemisphere would be considered a threat to the United States.

Even the great regional battles over extending slavery westward didn’t scuttle Monroe’s efforts to create a new political era. In March 1820, three weeks after signing the Missouri Compromise , Monroe set out on a four-month, 5,000-mile tour of the South, where his success at getting the Spanish out of Florida was wildly popular. Charleston and Savannah, especially, celebrated Monroe with such zeal that a Georgia newspaper declared Savannah was “in danger of overdoing it.” Monroe visited Jackson at his Tennessee home, The Hermitage, and spoke at the Nashville Female Academy, the country’s largest school for women, before swinging back to Washington in August.

Of course, the “Good Feelings” nickname only applied to those who could enjoy the rights enshrined in the Constitution. Native Americans, enslaved persons and other besieged groups would have had little “good” to say about the era. Nor would the huge number of Americans impoverished in the Panic of 1819.

Still, as Monroe had hoped, the Federalist Party died away. “A few old Federalists still moved around the capital, like statues or mummies,” wrote George Dangerfield in his 1952 book The Era of Good Feelings , but “all ambitious men called themselves Republicans, or sought, without undergoing a public conversion, to attach themselves to whatever Republican faction would best serve their interests.”

In 1820, Monroe won a second term essentially unopposed, with an Electoral College vote of 231 to 1. He felt he had carried out “the destruction of the federal party,” he wrote to Madison in 1822. “Our government may get on and prosper without the existence of parties.”

But the good feelings didn’t last. The U.S. forsook parties, but it couldn’t forsake politics.

Though historians disagree on when the era closed – some say it only lasted two years, ending with the Panic of 1819 -- ill feelings defined America’s mood by the end of Monroe’s second term. Without party discipline, governing got harder. By the early 1820s, it was every man for himself in Congress and even in Monroe’s cabinet: Secretary of State Adams, Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford, and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun all jockeyed to succeed Monroe as president.

The incident that best proves the Era of Good Feelings was over occurred in winter 1824. Crawford, furious at Monroe for not protecting his cronies during Army budget cuts, confronted him at the White House. “You infernal scoundrel,” the treasury secretary hissed, raising his cane at the president. Monroe grabbed fireplace tongs to defend himself, Navy Secretary Samuel L. Southard stepped between the men, and Crawford apologized and left the White House, never to return.

The 1824 presidential election, held without parties, attracted four candidates: Jackson, Adams, Crawford, and House Speaker Henry Clay. After none won an Electoral College majority, the House of Representatives elected Adams, the second-place finisher, as president – passing over Jackson, who’d won the most electoral votes and popular votes. That election provoked American politics to reorganize into a new two-party system—Jacksonian Democrats versus Adams’ Whigs.

Monroe died on July 4, 1831, with a substantial legacy in American history, from the Monroe Doctrine’s influence on foreign policy to his role in the nation’s westward expansion. But the nation never again neared his ideal of a party-free government. For better and for worse, through battles over economics and war, slavery and immigration, the two-party system he inadvertently spawned has defined American politics ever since.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Erick Trickey | | READ MORE

Erick Trickey is a writer in Boston, covering politics, history, cities, arts, and science. He has written for POLITICO Magazine, Next City, the Boston Globe, Boston Magazine, and Cleveland Magazine

The Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings (1815–1824) followed the Jeffersonian Era. It was an era of economic prosperity and geographic expansion, driven by the American System and the Monroe Doctrine. The era is closely associated with President James Monroe, the establishment of the Second Party System, the rise of Andrew Jackson, and the rise of Sectionalism. The Era of Good Feelings was followed by the Jacksonian Era.

President James Monroe. Image Source: Wikipedia.

Era of Good Feelings Summary

The Era of Good Feelings was a period in American history that started with unity and nationalism in the wake of the War of 1812 . In 1816, James Monroe , a Democratic-Republican , won a landslide victory against the Federalist candidate, Rufus King, signaling the decline of the Federalist Party, which had opposed the War of 1812. During Monroe’s first term, he traveled the nation, wearing his military uniform from the American Revolutionary War, rallying support for uniting the nation. Monroe’s first term was highlighted by economic growth, but the second term was plagued by Sectionalism, an economic depression, and division within his own political party. Due to the Election of 1824, Andrew Jackson and his supporters became the Democratic Party, ending the Era of Good Feelings and ushering in the Jacksonian Era.

Era of Good Feelings Facts

- The Era of Good Feelings was a period in American history from 1815 to 1824. It followed the Jeffersonian Era and preceded the Jacksonian Era.

- The Era of Good Feelings was marked by a sense of nationalism and patriotism following the War of 1812 and the signing of the Treaty of Ghent.

- The dominant political parties during this time were the Federalists , who favored a strong federal government, and the Democratic-Republicans, who supported a more limited government. However, the time period saw the decline of the Federalists, leaving the Democratic-Republicans as the only true political party.

- President James Monroe played an important role in diminishing the Federalist Party and promoting unity among Americans through his policies and tours across the country.

- The Era of Good Feelings was short-lived, as Sectionalism and the Presidential election of 1824 led to the emergence of new parties division that eventually led to the Civil War.

Era of Good Feelings History and Overview

The Era of Good Feelings started when the Treaty of Ghent went into effect in February 1815, ending the War of 1812. Although the war itself was a stalemate, Americans referred to it as the “Second War for Independence” and celebrated General Andrew Jackson’s victory over British forces at the Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815).

Nationalism and Prosperity Usher in the Era of Good Feelings

For the second time in less than 50 years, The United States had gone to war with Great Britain and held its own. In the aftermath, the nation was filled with a growing sense of pride and nationalism. As a result, Americans looked to raise the profile of the United States on the world stage and looked in a new direction for leadership.

The Hartford Convention

Near the end of the War of 1812, Federalists — the party of Adams and Hamilton — held the Hartford Convention (1814–1815) . During the Convention, which was largely attended by New England Federalists who opposed the War of 1812, several ideas were discussed — including secession and changes to the Constitution. The Convention was highly controversial and Jackson’s victory at New Orleans made any demands the Convention made a moot point.

The American System

The Convention is widely viewed as an unpopular, misguided attempt by Federalists that bordered on treason. In the wake of the party’s collapse, the feud with Democratic-Republicans ended, allowing President James Madison and Henry Clay to move ahead and implement the main components of the “American System” — protective tariffs, building roads and canals to connect the nation, and the establishment of a new national bank.

The first protective tariff was the Tariff of 1816, which added a 25% tax on all wool and cotton goods that were imported into the United States from foreign nations. Unfortunately, the Tariff of 1816 was viewed as detrimental to the South and may have helped suppress the development of manufacturing in those states.

Two of the most well-known infrastructure projects were the construction of the National Road and the Erie Canal . The National Road project started in 1811 in Cumberland, Maryland, and moved westward, following the military road that was opened by the Braddock Expedition during the French and Indian War . Work on the Erie Canal started in 1817 and finished in 1825. Both projects helped connect different parts of the country and helped expand the economy.

The third piece of the system was the Second Bank of the United States, which succeeded the First Bank of the United States . The Federal Government established the bank in 1816 to help stabilize the economy. The bank was given a 20-year charter but quickly created financial issues that contributed to the Panic of 1819.

Monroe Wins the Presidential Election of 1816

James Monroe, a Democratic-Republican, succeeded Madison as President. Monroe easily won the Election of 1816, defeating the Federalist Party candidate, Rufus King. King’s defeat was essentially the end of the Federalist Party.

Monroe’s Goodwill Tour

Following his election, Monroe embarked on a goodwill tour designed to decrease regional divisions that had emerged during the War of 1812. Following Monroe’s visit to Boston, the phrase “Era of Good Feelings” was coined by Benjamin Russell, and first appeared in the Federalist newspaper, Columbian Sentinel, on July 12, 1817.

A Soaring Economy Leads to the Panic of 1819

During the Era of Good Feelings, the American economy experienced a significant boom. However, land speculation was rampant, fueled by the expansion of banking and the creation of the Second Bank of the United States. Cotton prices soared, leading to increased production and economic growth. Unfortunately, the economic boom created challenges. The Panic of 1819 created an economic recession that lasted into the 1820s, causing a decline in economic prosperity.

Sectionalism and the Party System

The beginning of the era brought an end to the Federalist Party and the old First Party System. It allowed Monroe to essentially run unopposed for re-election in 1820 and win the Presidential Election of 1820. However, his last term in office saw the return of political division as the nation expanded geographically and differences rose over slavery and the rights of States. By the end of the era, the division within the Democratic-Republican Party helped shape the Second Party System, bringing an end to the unity that marked the beginning of the Era of Good Feelings.

McCulloch v. Maryland, an Important Decision by the Marshall Court

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) was one of the landmark court cases of the era. In an effort to support state banks, Maryland levied taxes on the Second Bank of the United States. When the Bank refused to pay, Maryland filed a lawsuit in Federal Court. The case made its way to the Supreme Court and Chief Justice John Marshall . The Supreme Court ruled the Bank had been incorporated by the Federal Government, pursuant to Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution — the “Necessary and Proper Clause.”

The Missouri Compromise Maintains an Uneasy Balance

The Missouri Compromise (1820) became a defining moment for the Era of Good Feelings. The admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state was intended to maintain a balance between the slave states and free states in the Union. However, the debate over the expansion of slavery and the disagreements over the practice foreshadowed the Sectionalism that would shape American politics in the years to come, leading to the Secession Crisis and Civil War.

The United States Establishes the Monroe Doctrine

In 1823, Monroe took action to establish the United States as a leader in the Western Hemisphere by establishing the “Monroe Doctrine.” Monroe warned European powers not to interfere in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere. The purpose of the Doctrine was to prevent European colonization and the establishment of puppet regimes in the Americas. Although the Doctrine was not well-enforced early on, it became a basic tenet of American foreign policy.

The Election of 1824 Leads to the Age of Jackson

In the Election of 1824, there were multiple candidates for President, including John Quincy Adams , Andrew Jackson, and Henry Clay — and they were all Democratic-Republicans. While John C. Calhoun was elected Vice-President, the election for the President went to the House of Representatives. Adams emerged as the winner — and appointed Clay as his Secretary of State. The move enraged Jackson and his supporters, who believed Adams and Clay conspired against them. The Jacksonians called it the “Corrupt Bargain.” The perception of a backroom political deal helped fuel the divide in the Democratic-Republican Party. In 1828, Andrew Jackson won the Presidency, ushering in the Age of Jackson, also known as the Jacksonian Era.

Era of Good Feelings Significance

The Era of Good Feelings is important to United States history because it was the time when the United States started to experience Sectionalism due to slavery, economics, and political parties. Although the time period started on a high note following the War of 1812, it ended in a political division that led to the emergence of Andrew Jackson as a candidate for President.

Era Of Good Feelings Frequently Asked Questions

The emergence of the Era of Good Feelings after the War of 1812 can be attributed to several factors. First, the war marked a sense of national pride and unity among Americans, leading to a surge of patriotic sentiments. The Treaty of Ghent, which ended the war, further strengthened the nation’s confidence and heightened its nationalism. Additionally, the election of James Monroe as president in 1816, with his message of national harmony, played a crucial role in fostering a sense of unity and optimism in the country.

The Second Bank of the United States, chartered in 1816, had a significant impact on the economy during the Era of Good Feelings. It aimed to create a more stable currency system by regulating the money and credit supply. The bank facilitated economic growth by providing access to credit and promoting sound financial practices. It also helped regulate state banks and stabilize the national economy. However, the bank’s policies, particularly its pursuit of profit, contributed to inflation, speculation, and the eventual Panic of 1819, which resulted in an economic downturn.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 was a significant legislative measure aimed at addressing the issue of slavery expansion in the United States. It allowed Missouri to enter the Union as a slave state while admitting Maine as a free state, maintaining the balance of power between free and slave states in the Senate. Additionally, the compromise established the 36°30′ line as a dividing line between free and slave territories within the Louisiana Purchase . North of this line, slavery was prohibited, while south of it, it remained legal. The Missouri Compromise played a pivotal role in temporarily calming sectional tensions but also brought the deep divide over slavery in the United States to the forefront of the political landscape.

The Monroe Doctrine , introduced by President James Monroe in 1823, outlined American foreign policy regarding European involvement in the Western Hemisphere. It stated that the United States would consider any further colonization attempts by European powers in the Americas as acts of aggression. Additionally, the doctrine emphasized non-interference in the existing European colonies in the Western Hemisphere and asserted the United States’ commitment to neutrality in European conflicts. The Monroe Doctrine established a foundation for American hegemony in the Americas, aimed to limit European influence, and became a cornerstone of U.S. foreign policy.

The “Corrupt Bargain” refers to the alleged political deal struck between John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay during the Election of 1824. After no candidate secured a majority in the Electoral College, the House of Representatives decided the outcome. Adams announced Clay as his choice for Secretary of State shortly after his victory in the House vote, which angered Andrew Jackson and his supporters. The perceived agreement plagued the Presidency of John Quincy Adams and fueled accusations of political manipulation. It contributed to the rise of Andrew Jackson and the emergence of a more partisan political era, ending the Era of Good Feelings.

The Era of Good Feelings AP US History (APUSH) Overview

This section provides terms, definitions, and Frequently Asked Questions about the Era of Good Feelings, including people, events, and programs. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Era of Good Feelings APUSH Definition

The Era of Good Feelings refers to a period of relative political harmony and national unity in the United States that occurred from approximately 1817 to 1825. Taking place during James Monroe’s presidency, this era was characterized by a decline in partisan conflicts, with the Federalist Party losing influence. It was a time of economic growth, territorial expansion, and a sense of American nationalism. However, underlying tensions, such as sectional disputes over slavery, led to the emergence of new political parties.

The Era of Good Feelings Explained

This video from Heimler’s History includes an overview of the Era of Good Feelings for the AP US History exam.

Era of Good Feelings APUSH Terms and Definitions

Important people during the era of good feelings.

John C. Calhoun — John C. Calhoun was an American statesman and politician who served as the seventh Vice President of the United States from 1825 to 1832. He was a prominent defender of States’ Rights and slavery and played a significant role in the political debates of the early 19th century.

Henry Clay — Henry Clay was an American statesman and political leader who served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. Secretary of State. Clay, who was a member of the Whig Party, is best known for his role in shaping U.S. foreign and domestic policy in the early 19th century. He is remembered for his advocacy of the American System, a plan for economic development that included a national bank, a protective tariff, and federal funding for infrastructure projects.

Andrew Jackson — Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States , serving from 1829 to 1837. He was a military officer and politician from Tennessee who had a controversial and influential tenure as President. Jackson was known for his strong personality and his advocacy for a more democratic and representative government. He is best known for his role in the Indian Wars of the period and for his support for States’ Rights.

James Madison — James Madison was a Founding Father who played a crucial role in the drafting and ratification of the United States Constitution. Serving as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817, Madison is known for his contributions to the War of 1812 and for advocating for a strong central government. He is often referred to as the “Father of the Constitution.”

James Monroe — James Monroe was a Founding Father and the fifth president of the United States , serving from 1817 to 1825. Monroe is best known for his Monroe Doctrine, which asserted U.S. opposition to European colonization in the Americas and established the United States as the dominant power in the Western Hemisphere. His presidency was characterized by a period of national unity and economic growth known as the “Era of Good Feelings.”

War of 1812 and the Era of Good Feelings

War of 1812 — The War of 1812 — which some Americans referred to as the “Second War for Independence” — was fought between the United States and Great Britain from 1812 to 1815. The war was sparked by a variety of issues, including British interference with American trade and the impressment of American sailors by the British navy. The war was marked by several significant military engagements, including the Battle of Lake Erie and the Battle of New Orleans. The war ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent in 1815, ushering in the Era of Good Feelings.

Battle of New Orleans — The Battle of New Orleans was a military engagement that took place during the War of 1812. The battle, which was fought in January 1815, involved a force of British soldiers and a force of American soldiers led by Andrew Jackson. The American forces were victorious, leaving Americans with a sense they had won the “Second War for Independence.”

Treaty of Ghent (1815) — The Treaty of Ghent was a peace treaty that was signed in December 1814 between the United States and Great Britain to end the War of 1812. The treaty, which was negotiated in the Belgian city of Ghent, established the status quo ante bellum, meaning that the territory and boundaries of the two countries would be returned to their pre-war status. The treaty was ratified by both sides, but it did not take effect until after the Battle of New Orleans, which was fought after the treaty was signed. The United States formally ratified the treaty in 1815.

The American System and the Era of Good Feelings

American System — The American System was a plan for economic development that was proposed by Henry Clay and other members of the Whig Party in the early 19th century. The American System included a number of policy proposals, including the establishment of a national bank, the implementation of a protective tariff, and federal funding for infrastructure projects. The American System was designed to promote economic growth and development in the United States and became an important part of the political platform of the Whig Party.

Second Bank of the United States — The Second Bank of the United States was a national bank chartered by the U.S. Congress in 1816. The bank, which was established to serve as a central bank for the United States, was intended to regulate the national currency and provide financial stability. The bank was controversial, and its charter was not renewed when it expired in 1836, leading to the establishment of a decentralized banking system in the United States.

Erie Canal — The Erie Canal was a canal that was built in the early 19th century to connect the Great Lakes with the Hudson River in New York. The canal, which was completed in 1825, was a major engineering feat and played a significant role in the economic development of the United States. The canal, which allowed for the transportation of goods and people between the East Coast and the Midwest, helped to spur the growth of towns and cities along its route and facilitated the expansion of trade and commerce.

National Road (Cumberland Road) — The National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road, was a federally funded road that was built in the early 19th century to connect the East Coast of the United States with the Midwest. The road, which was authorized by the U.S. Congress in 1806, was the first major federally funded infrastructure project in the United States and played a significant role in the development of the country’s transportation system.

Nicholas Biddle — Nicholas Biddle was an American financier and political figure who served as the president of the Second National Bank of the United States from 1823 to 1836. Biddle, who was a strong advocate for the bank, played a significant role in shaping the bank’s policies and practices. He is remembered for his role in the controversy surrounding the bank’s charter and for his impact on the financial system of the United States.

Protective Tariff — A protective tariff is a tariff that is imposed on imported goods in order to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. Protective tariffs are designed to make imported goods more expensive than similar domestic products, which can help to promote domestic production and protect domestic jobs. Protective tariffs are a controversial policy tool and are often opposed by those who believe they lead to higher prices for consumers and can lead to trade disputes with other countries.

Robert Fulton and Steamboats — Robert Fulton was an American inventor and engineer who is best known for his development of the steamboat. Fulton, who is credited with building the first commercially successful steamboat, the Clermont , played a significant role in the development of the steam-powered transportation industry in the United States. His work helped to revolutionize transportation and played a key role in the growth and development of the country.

Tariff of 1816 — The Tariff of 1816 was a tariff, or tax on imported goods, enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1816. The tariff, which was one of the first to be imposed by the U.S. government, was intended to protect domestic industries from foreign competition and to provide revenue for the federal government. The tariff was controversial and was opposed by some who believed it would lead to higher prices for consumers.

Events During the Era of Good Feelings

Panic of 1819 — The Panic of 1819 was a financial crisis that occurred in the United States in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The crisis, which was triggered by a number of factors, including over-speculation and a downturn in international trade, led to a widespread economic depression and contributed to the recession that followed.

The Judicial System During the Era of Good Feelings

Implied Powers — Implied powers are powers that are not explicitly listed in the U.S. Constitution but are inferred from the broader powers granted to the federal government. Implied powers are a key aspect of the “elastic clause,” also known as the “necessary and proper clause,” which gives Congress the authority to pass any laws that are necessary and proper for carrying out its powers and duties. The concept of implied powers has been a source of controversy and debate in American politics, as it has been used to justify a broad range of federal actions and policies.

McCulloch v. Maryland (1819 ) — McCulloch v. Maryland was a landmark case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1819. The case arose when James McCulloch, the cashier of the Bank of the United States, was sued by the state of Maryland for failing to pay a tax on the bank’s operations. The Court, in a unanimous decision written by Chief Justice John Marshall , ruled that the state of Maryland did not have the authority to tax the Bank of the United States, as it was a federal institution. The decision in McCulloch v. Maryland established the principle that federal law takes precedence over state law.

Dartmouth College v. Woodford (1819) — Dartmouth College v. Woodford was a case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1819. The case arose when Daniel Woodford, the governor of New Hampshire, attempted to revoke the charter of Dartmouth College, which had been granted by the state of New Hampshire. The Court, in a unanimous decision written by Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled that the charter of Dartmouth College was a contract that could not be impaired by the state of New Hampshire. The decision in Dartmouth College v. Woodford established the principle of the “contract clause,” which protects contracts from being impaired by state action.

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) — Gibbons v. Ogden was a landmark case decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1824. The case arose when Aaron Ogden, a steamboat operator, sued Thomas Gibbons, a rival steamboat operator, for violating a monopoly on steamboat traffic in New York state. The Court, in a unanimous decision written by Chief Justice John Marshall, ruled that the federal government had the authority to regulate interstate commerce and that the monopoly granted by the state of New York was invalid. The decision in Gibbons v. Ogden established the principle of federal supremacy in matters of interstate commerce.

Slavery During the Era of Good Feelings

Denmark Vesey — Denmark Vesey was an African American slave who planned a slave revolt in the United States in 1822. Vesey, who had purchased his freedom, was a leader in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was deeply concerned about the plight of enslaved people in the United States. He was arrested and executed for his role in the planned revolt, which was thwarted before it could take place.

King Cotton — “King Cotton” was a slogan used to describe the economic dominance of the cotton industry in the southern United States in the 19th century. Cotton was the main cash crop of the southern states, and it played a central role in the economy and society of the region. The slogan was used to highlight the importance of the cotton industry to the South and the power that it wielded within the region.

Missouri Compromise (1820) — The Missouri Compromise was an agreement that admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, and established the 36°30′ parallel as the dividing line between slave and free states in the Louisiana Purchase territory. The compromise was seen as a temporary solution to the issue of slavery expansion, but it ultimately contributed to the growing tensions between the North and South that led to the Civil War.

Peculiar Institution — The “Peculiar Institution” was a term used to describe slavery in the United States. The term was often used by defenders of slavery to emphasize the unique nature of the institution in the United States and to suggest that it was not a typical form of slavery. The peculiar institution of slavery was a major cause of conflict in the United States, and it played a central role in the Civil War and the abolition of slavery.

Slave Codes — Slave codes were laws that governed the lives of enslaved people in the United States. These laws varied from state to state, but they generally served to restrict the rights and freedoms of enslaved people and to reinforce the power of their owners. Slave codes prohibited enslaved people from owning property, learning to read or write, or traveling without permission. They also imposed severe penalties for any perceived violations of the codes, including whipping, branding, and execution. Slave codes were a key aspect of the institution of slavery in the United States and were a major source of conflict between slaveholders and abolitionists.

Politics In the Era of Good Feelings

Two Party System — The Two Party system refers to the political system in the United States in which there are two dominant political parties, the Democrats and the Republicans. The Two Party System has been a feature of American politics since the early 19th century.

John Quincy Adams and the Corrupt Bargain — John Quincy Adams was the sixth President of the United States , serving from 1825 to 1829. He was the son of John Adams, the second President of the United States. Adams was elected in a highly controversial election in which he lost the popular vote but won the presidency in the House of Representatives. His victory was seen by many as the result of a “Corrupt Bargain” with Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House, and Adams faced significant opposition during his presidency as a result.

Election of 1828 — A presidential election in the United States in which Andrew Jackson, a Democrat, defeated John Quincy Adams, a National Republican, to become the seventh president of the United States. The campaign was marked by harsh personal attacks and political maneuvering, and it is often seen as a turning point in American politics, as it marked the end of the “Era of Good Feelings” and the beginning of the Two-Party system.

First Party System — The First Party System was a political arrangement that emerged in the United States in the late 18th century. It was characterized by the rivalry between the Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. This system shaped early American politics and established the foundation for party-based competition and policy debates.

Hartford Convention — The Hartford Convention was a meeting of Federalist Party leaders that was held in Hartford, Connecticut in 1814. The Hartford Convention was called in response to the perceived failures of the James Madison administration during the War of 1812 and the declining fortunes of the Federalist Party. The Hartford Convention was characterized by a series of debates and discussions about the future of the Federalist Party and the role of the federal government in the United States. The Hartford Convention was seen as a significant moment in the decline of the Federalist Party, and it is often cited as a key factor in the party’s eventual demise. The Federalist Party had been one of the dominant political parties in the United States in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but it began to lose support in the aftermath of the War of 1812 and the Hartford Convention. The party was seen as elitist and out of touch with the needs of the American people, and it struggled to adapt to the changing political landscape of the early Republic. The Federalist Party declined in the years following the Hartford Convention and eventually disappeared from the national stage.

Second Party System — The Second Party System emerged in the United States in the 1820s and lasted until the 1850s. It was marked by the competition between the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which opposed Jackson’s policies. This system saw the rise of national political conventions, mass participation in elections, and intense political campaigning. It also reflected the growing sectional tensions over issues such as slavery, ultimately leading to the Civil War.

Sectionalism — Sectionalism refers to the tendency for regions or sections of a country to have distinct economic, social, and political interests that may conflict with those of other regions. In the United States, sectionalism has often been driven by differences in the economic and social development of different regions of the country. For example, the North and South had very different economies in the 19th century, with the North being more industrialized and the South being more reliant on agriculture. These differences led to conflicts and tensions between the two regions and played a significant role in the development of the U.S. political system.

Virginia Dynasty — The Virginia Dynasty refers to a period in U.S. history in which four of the first five U.S. presidents were from Virginia. The Virginia Dynasty began with Thomas Jefferson , who was the third U.S. president and served from 1801 to 1809. It was followed by James Madison, who served as the fourth U.S. president from 1809 to 1817, and James Monroe, who served as the fifth U.S. president from 1817 to 1825. The Virginia Dynasty ended with John Quincy Adams, who was the sixth U.S. president and served from 1825 to 1829. The Virginia Dynasty is significant because it marked a period of stability and prosperity in the United States, and it is often seen as a high point in the country’s early history.

The Effects of Manifest Destiny and Westward Expansion on the Era of Good Feelings

Rush-Bagot Agreement (1817) — The Rush-Bagot Agreement was a treaty signed in 1817 between the United States and Great Britain that established the borders between the two countries in the Great Lakes region and limited the number of armed vessels that each country could maintain on the lakes. The agreement, which was signed by U.S. Secretary of State James Monroe and British diplomat Charles Bagot, was a significant step towards reducing tensions between the two countries and establishing peaceful relations.

Treaty of 1818 (1818) — The Treaty of 1818 was a treaty signed in 1818 between the United States and Great Britain that established the border between the two countries in the Pacific Northwest and established the terms for joint occupancy of the Oregon Country. The treaty, which was signed by U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and British diplomat Richard Rush, was a significant step towards resolving disputes between the two countries and establishing peaceful relations.

Adams-Onis Treaty (1819) — The Adams-Onis Treaty, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty , was a treaty signed in 1819 between the United States and Spain that established the boundary between the two countries in North America. The treaty, which was signed by U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and Spanish diplomat Luis de Onis, was a significant step towards resolving disputes between the two countries and establishing peaceful relations.

Foreign Policy in the Era of Good Feelings

Monroe Doctrine (1823) — The Monroe Doctrine was a statement issued by U.S. President James Monroe in 1823 that declared the Western Hemisphere to be off-limits to European colonization and established the United States as the dominant power in the region. The doctrine, which was issued in response to increasing European intervention in the affairs of Latin American countries, was a significant statement of American foreign policy and played a significant role in shaping the political landscape of the Americas in the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Content for this article has been compiled and edited by Randal Rust .

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

Our Collection

At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in American history. More than 65,000 items cover five hundred years of American history, from Columbus’s 1493 letter describing the New World to soldiers’ letters from World War II and Vietnam. Explore primary sources, visit exhibitions in person or online, or bring your class on a field trip.

At the Institute’s core is the Gilder Lehrman Collection, one of the great archives in American history. More than 85,000 items cover five hundred years of American history, from Columbus’s 1493 letter describing the New World through the end of the twentieth century.

Advanced Search

- Exhibitions

- Spotlighted Resources

- Rights & Reproductions

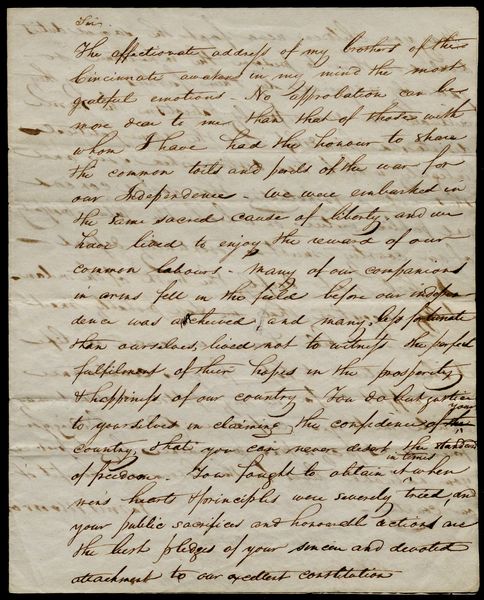

Monroe, James (1758-1831) [Speech to Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati]

High-resolution images are available to schools and libraries via subscription to American History, 1493-1943 . Check to see if your school or library already has a subscription. Or click here for more information. You may also order a pdf of the image from us here .

A high-resolution version of this object is available for registered users. LOG IN

Gilder Lehrman Collection #: GLC00069 Author/Creator: Monroe, James (1758-1831) Place Written: Boston, Massachusetts Type: Manuscript signed Date: 4 July 1817 Pagination: 2 p. : docket ; 25 x 20 cm. Order a Copy

President Monroe acknowledges the passing of the Revolutionary generation and movingly recalls their struggle in the "sacred cause of liberty." A signed transcription of Monroe's Independence Day speech to the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati. The president's original remarks were made on his 1817 reconciliation tour through New England. Date from later docketing.

Early in the summer of 1817, as a conciliatory gesture toward the Federalists who had opposed the War of 1812, President James Monroe embarked on a goodwill tour through the Northeast and what is now the Midwest. Everywhere Monroe went, citizens held parades and banquets in his honor. In Federalist Boston, a crowd of 40,000 welcomed the Republican president. A Federalist newspaper called the times "the era of good feelings." James Monroe was the popular symbol of the era of good feelings. His life embodied much of the history of the young republic. He had joined the Revolutionary army in 1776 and spent the terrible winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge. He had been a member of the Confederation Congress and performed double duty as Secretary of State and of War during the War of 1812. The last President to don the fashions of the eighteenth century, Monroe wore his hair in a powdered wig and favored knee breeches, long white stockings, and buckled shoes. His political values, too, were those of an earlier day. Like George Washington, he hoped for a country without political parties, governed by leaders chosen on their merits. So great was his popularity that he won a second presidential term by an electoral college vote of 231 to 1. Here, Monroe replies to an address of the Massachusetts Society of the Cincinnati, an organization of surviving Revolutionary war officers.

Sir. The affectionate address of my brothers of the Cincinnati awakens in my mind the most grateful emotions -country. No approbation can be more dear to me than that of those with whom I have had the honour to share the common toils and perils of the war for our Independence - We were embarked in the same sacred cause of liberty, and we have lived to enjoy the reward of our common labours - Many of our companions in arms fell in the field before our independence was acheived, and many less fortunate than ourselves, lived not to witness the perfect fulfilment of thier hopes in the prosperity & happiness of our country - You do but justice to yourselves in claiming the confidence of your country, that you can never desert the standard of freedom - You fought to obtain it in times when men's hearts & principles were severely tried, and your public sacrifices and honoarable actions are the best pledges of your sincere and devoted attachment to our excellent constitution. May your children never forget the sacred duties devolved on them to preserve the inheritance so gallantly acquired by their fathers - May they cultivate the same manly patriotism, the same disinterested friendship and the same political integrity, which has distinguished you, and thus unite in perpetuating that social concord and public virtue on which the future prosperity of our country must so essentially depend - I feel most deeply the truth of the melancholy suggestion, that we shall probably meet no more - While however we remain in life I shall continue to hope for your countenance and support so far as my public conduct may entitle me to your confidence; and in bidding you farewell, I pray a kind providence long to preserve your valuable lives for the honour and benefit of our country.

James Monroe to his Excellency Governor Brooks President of the Cincinnati of Massachusetts

[address leaf:] Reply of James Monroe James Monroe to an address of President of the U States. the Mass. Soc. of the Cincin his answer to the Cin- -nati - to him as Doubtless on his visit to a brother member. Boston in 1817. James M. Sever 4th. July 1817. - 1860

He being President Cincinnati Papers. of the United States without Dates. on his visit to Boston. Boston Jany 25 1836. Thos. Jackson

Citation Guidelines for Online Resources

Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

James Monroe

James monroe was the fifth president of the united states (1817–1825) and the last president from the founding fathers..

On New Year’s Day, 1825, at the last of his annual White House receptions, President James Monroe made a pleasing impression upon a Virginia lady who shook his hand:

“He is tall and well formed. His dress plain and in the old style…. His manner was quiet and dignified. From the frank, honest expression of his eye … I think he well deserves the encomium passed upon him by the great Jefferson, who said, ‘Monroe was so honest that if you turned his soul inside out there would not be a spot on it.’ ”

Born in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1758, Monroe attended the College of William and Mary, fought with distinction in the Continental Army, and practiced law in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

As a youthful politician, he joined the anti-Federalists in the Virginia Convention which ratified the Constitution, and in 1790, an advocate of Jeffersonian policies, was elected United States Senator. As Minister to France in 1794-1796, he displayed strong sympathies for the French cause; later, with Robert R. Livingston, he helped negotiate the Louisiana Purchase.

His ambition and energy, together with the backing of President Madison, made him the Republican choice for the Presidency in 1816. With little Federalist opposition, he easily won re-election in 1820.

Monroe made unusually strong Cabinet choices, naming a Southerner, John C. Calhoun, as Secretary of War, and a northerner, John Quincy Adams, as Secretary of State. Only Henry Clay’s refusal kept Monroe from adding an outstanding Westerner.

Early in his administration, Monroe undertook a goodwill tour. At Boston, his visit was hailed as the beginning of an “Era of Good Feelings.” Unfortunately these “good feelings” did not endure, although Monroe, his popularity undiminished, followed nationalist policies.

Across the facade of nationalism, ugly sectional cracks appeared. A painful economic depression undoubtedly increased the dismay of the people of the Missouri Territory in 1819 when their application for admission to the Union as a slave state failed. An amended bill for gradually eliminating slavery in Missouri precipitated two years of bitter debate in Congress.

The Missouri Compromise bill resolved the struggle, pairing Missouri as a slave state with Maine, a free state, and barring slavery north and west of Missouri forever.

In foreign affairs Monroe proclaimed the fundamental policy that bears his name, responding to the threat that the more conservative governments in Europe might try to aid Spain in winning back her former Latin American colonies. Monroe did not begin formally to recognize the young sister republics until 1822, after ascertaining that Congress would vote appropriations for diplomatic missions. He and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams wished to avoid trouble with Spain until it had ceded the Floridas, as was done in 1821.

Great Britain, with its powerful navy, also opposed reconquest of Latin America and suggested that the United States join in proclaiming “hands off.” Ex-Presidents Jefferson and Madison counseled Monroe to accept the offer, but Secretary Adams advised, “It would be more candid … to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war.”

Monroe accepted Adams’s advice. Not only must Latin America be left alone, he warned, but also Russia must not encroach southward on the Pacific coast. “. . . the American continents,” he stated, “by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European Power.” Some 20 years after Monroe died in 1831, this became known as the Monroe Doctrine.

The Presidential biographies on WhiteHouse.gov are from “The Presidents of the United States of America,” by Frank Freidel and Hugh Sidey. Copyright 2006 by the White House Historical Association.

Learn more about James Monroe ‘s spouse, Elizabeth Kortright Monroe .

- (434) 293-8000

- info@highland.org

Open from 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

- Highland Rustic Trails

- Group Programs

The Era of Good Feelings

– Portrait of James Monroe by John Vanderlyn, 1816

“During the late Presidential Jubilee many persons have met at festive boards, in pleasant converse, whom party politics had long severed. We recur with pleasure to all the circumstances which attended the demonstrations of good feelings.”

– Columbian Centinel , July 12, 1817.

No president since George Washington travelled as extensively as James Monroe did during his 1817 tour of the northern United States. Beginning in Baltimore, Monroe visited over a hundred cities across eleven states, along with the Michigan Territory. Monroe intended to inspect post-war fortifications, but his presence North, a traditional cradle of federalism, also demonstrated his commitment to national unity. Boston’s Columbian Centinel recognized the sense of nationalism surrounding his tour and christened his first presidential term the “Era of Good Feelings.” Former political rivals greeted him in Boston, illustrating their support for the new administration. Likewise, the journey to Detroit solidified his approval among frontiersmen who now believed they were part of the burgeoning nation.

The organized factions George Washington warned about in his farewell address certainly impeded the United States’ success during the War of 1812. Monroe wrote about these political divisions in The People The Sovereigns , considering them a cause of many ancient republic’s decline. Therefore, at the onset of his presidency, Monroe appointed only Democratic-Republicans with the aim of eliminating party conflicts for good. Democratic-Republicans, however, adopted many of the Federalist Party’s objectives after the war, which naturally produced a one party system within the United States. Baltimore’s Federal Republican commented on this merger, noting that “the nearer the Democratic administration and party come up to the old federal principles and measures, the better they act and the more we prosper…” But as the Era of Good Feelings progressed, political infighting and sectional disputes replaced old party lines. Though only one electoral vote went against Monroe in the 1820 election , the Democratic-Republican party experienced significant disunity during his second term based on sectional disagreements, particularly over slavery.

The different document types introduce varying interpretations of Monroe’s presidency and northern tour. The Columbian Centinel coined the era’s monicker, and the Detroit Gazette elaborated on the feelings Monroe’s tour brought to the territory. Abigail Adams praised the President’s visit to Boston, describing the way he impressed the citizenry and embodied nationalism in post-war America, supporting the notion that this was indeed the Era of Good Feelings.

Document Based Questions

- What happened to party politics in the United States?

- How did the editor describe the dinner reception hosted by former President John Adams?

- What political parties did the guests belong to, and how did this acknowledgment support the unifying themes of the Era of Good Feelings?

- Why would the editor include a list of guests in attendance, along with their titles?

- What impression did James Monroe’s tour have on the people of New England?

- Which places did James Monroe visit and review while in New England?

- How did Abigail Adams hope James Monroe would be upon his return from the tour?

- What does Abigail Adams’ authorship of this letter, and her description of James Monroe, reveal about the attitudes of Federalist Party members during this time?

- How did the people of Detroit react upon hearing of the President’s arrival?

- What impact did the War of 1812 have on the changing character and attitudes of Americans?

- How did Major Charles Larned contrast James Monroe from his predecessors?

- What changes did Major Charles Larned hope Congress would make to benefit the Michigan Territory?

- Why would Congress do nothing over the issues with Spain regarding the Florida Treaty?

- What replaced “the old line of demarcation between [political] parties?”

- How did John Quincy Adams describe the two presidential terms of James Monroe differently?

- Why were South American countries unhappy with the United States and its foreign policy?

- Why was President James Monroe not concerned about the “Missouri slave question?”

- What were some reasons John Quincy Adams believed the Era of Good Feelings was ending?

Essential Questions

- Why is the period following the War of 1812 considered the Era of Good Feelings?

- How much did James Monroe’s presidency contribute to the Era of Good Feelings?

- How impactful was James Monroe’s national tour in achieving national unity?

- Was the Era of Good Feelings really an era of national unity and political harmony?

Virginia Standards of Learning

CE.1 The student will demonstrate skills for historical thinking, geographical analysis, economic decision making, and responsible citizenship by

d) determining the accuracy and validity of information by separating fact and opinion and recognizing bias.

USI.7 The student will apply social science skills to understand the challenges faced by the new nation by

c) describing the major accomplishments of the first five presidents of the United States.

National Standards for Social Studies

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation

Standard 3D

Era 4: Expansion and Reform

Standard 3B

Bibliography & Suggested Readings

Ammon, Harry. “The Era of Good Feelings: Ideal” and Era of Good Feelings: Reality,” in James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1990. pp. 366-395.

Cooper, Kaitlyn. “Frontier Nationalism: President Monroe Visits Detroit,” in Border Crossings: The Detroit River Region in the War of 1812, ed. Denver Brunsman, Joel Stone, and Douglas D. Fisher. Detroit: Detroit Historical Society, 2012. pp. 244-254.

Marrone, Daniel S. “Promoting the Era of Good Feelings: James Monroe and Elizabeth Monroe’s Supportive Partnership.” American Spirit 150, no. 2 (March/April 2016): pp. 22-27.

McGrath, Tim. “‘The Happy Situation of the United States,’” in James Monroe: A Life. New York: Dutton, 2020. pp. 379-402.

McManus, Michael J. “President James Monroe’s Domestic Policies, 1817–1825: ‘To Advance the Best Interests of Our Union,’” in A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe , ed. Stuart Leibiger. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2013. pp. 438–455.

Moore, Glover. “Monroe’s Re-Election in 1820.” Mississippi Quarterly 11 (Summer 1958): pp. 131-140.

- Shopping Cart

- Become a Friend

- Plan Your Visit

- Need Research?

- Archives Department Collecting Guidelines

- How to Donate Your Materials

- Online Card Catalog

- Temporarily Unavailable Collections

- Treasures Collection

- Overview of Research Tools

- Patron Access Link (PAL)

- Discover (Online Catalog)

- Digital Library

- Exclusive Databases

- Reading Room Databases

- Finding Aids

- Subject Guides

- Balch Manuscript Guide

- Card Catalogs

- Greenfield Center for 20th-Century History

- Research Strategy Interviews

- InterLibrary Loan Service

- Research By Mail

- Rights and Reproductions

- PACSCL Survey Database

- Preserving the Records of the Bank of North America

- Neighbors/Vecinos

- Closed for Business: The Story of Bankers Trust Company during the Great Depression

- Freedom Quiz Answers

- About the PAS Papers

- John Letnum, 1786

- Hunt v. Antonio, 1797

- Colonel Dennis v. James Fox, 1822

- David Davis v. Elijah Clark, 1787

- George Stiles v. Daniel Richardson, 1797-99

- Marshall Green and Susan, 1826

- Two persons from Maryland, 1830

- Robinson's narrative concerning Robert, 1788

- In Re: Rudy Boice, 1794

- Forquiau v. Marcie and Children, 1805

- Commonwealth v. Lambert Smyth

- Cases before Michael Rappele, 1816

- "Ann Clark's case," 1818

- Lett, Philadelphia 1785

- Thirteen Blacks Freed…1785

- Negro Bob, Philadelphia, 1785

- Thomas Cullen v. Susanna, 1785

- Negro Nancy, Philadelphia, 1786

- Negro Darby v. Armitage, 1787

- D. Boadley, Philadelphia, 1787

- Commonwealth v. John Stokes, 1787 (Jethro & Dinah)

- Lydia, Philadelphia. 1789

- PA v. Blackmore, 1790

- Phoebe, Philadelphia. 1791

- Betty v. Horsfeld, 1792

- Irvine Republica v. Gallagher, 1801

- Mary Thomas, Philadelphia. 1810

- James Grey et al, 1810

- Vigilance Committee Accounts

- Junior Anti-Slavery Society Constitution

- Manumissions, Indentures, and other

- Pero, Philadelphia, 1791

- Manumission of 28 slaves by Richard Bayley, 1792

- Student Handwriting Samples

- Clarkson Hall

- Teachers' Reports

- PAS Correspondence

- PAS in Context: A Timeline

- The PAS and American Abolitionism

- William Still Digital History Project

- Anonymous No More: John Fryer, Psychiatry, and the Fight for LGBT Equality

- Digital Paxton

- The Tobias Lear Journal: An Account of the Death of George Washington

- Historic Images, New Technologies

- Philadelphia History Channel

- Explore Philly

- Staff & Editorial Advisory Committee

- Calls for Papers

- Submission Guidelines

- Special Issues

- Permissions

- Advertising

- Back Issues

- Primary Sources

- Topical Resource Guides

- Landmark Lessons

- Field Trip & Outreach Program Descriptions

- Educators Blog

- Professional Development

- Researching the Collection Online for Students

- Tips for Doing Research

- Student Guide to Visiting HSP

- How to Apply

- What will the Workshop be Like?

- Where will this Happen?

- Why Study Independence Hall?

- Sponsoring Organizations

Search form

In the spirit of the people: james monroe's 1817 tour of the northern states.

James Monroe became the fifth president of the United States in March, 1817. Three months later he embarked on a fifteen-week tour of the northern states, traveling up the east coast from Washington, DC to Portland, Maine; west to Detroit; and back to Washington via Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and Maryland, totaling some 2,000 miles.

Modern-day presidents are readily recognizable by almost every American. This was not true two hundred years ago. Monroe’s predecessors rarely traveled, and there was, of course, no electronic media continually broadcasting the president’s image or the sound of his voice. Monroe’s tour therefore created a national sensation. Americans came out by the thousands, thrilled by the opportunity to see the president, and newspapers across the country gave day-by-day accounts of his progress. Political differences were forgotten as Americans of both parties joined together in grand celebrations marked by parades, speeches, dinners, balls, receptions, and concerts. A Boston newspaper coined the phrase “Era of Good Feelings” to describe the national unity created by Monroe’s tour. The term became the catch-phrase of his presidency.

In collaboration with the James Monroe Museum and The Papers of James Monroe, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania will host In the Spirit of the People: James Monroe's 1817 Tour of the Northern States , a traveling exhibit commemorating the bicentennial of an historic presidential tour.

The exhibit is a joint project of The James Monroe Museum and The Papers of James Monroe , both of which are administered by the University of Mary Washington (UMW) in Fredericksburg, Virginia. The museum, founded in 1927 by Monroe descendants, is a National Historic Landmark housing the largest single collection of artifacts and archives related to the fifth president. The Papers of James Monroe is a publication project that has produced six volumes to date of selected official and personal correspondence pertaining to Monroe's long career in public service. The University of Mary Washington is a public university in Virginia that focuses on undergraduate education in the liberal arts and sciences. Signature degree programs include a major in historic preservation and minor in museum studies, both of which emphasize hands-on learning. Students in the university's museum studies program worked on all aspects of In the Spirit of the People , from research and image acquisition to copy writing and graphic design.

History Bytes: President James Monroe’s Visit to Newport

Two hundred years ago today, on June 28 1817, Newport hosted a visit by President James Monroe as he travelled through New England. The president arrived from Stonington, Connecticut on the famed U.S. Revenue Cutter VIGILANT accompanied by Capt. John Cahoone, Oliver Hazard Perry (most noted for his heroic role in the Battle of Lake Erie), and other dignitaries. Salutes were fired from Fort Adams and Fort Wolcott as the schooner toured the harbor. Later, President Monroe visited Tonomy Hill with its commanding view of the town and bay, and attended a reception with Rhode Island governor Nehemiah Knight and a welcoming committee. The following day, President Monroe attended services at the Episcopal, Baptist, and Congregational churches. He later paid a special visit to William Ellery, one of four surviving signers of the Declaration of Independence. At the end of the day, the president visited manufacturing sites at Fall River, then sailed to Bristol and Providence.

Image: Building contract for the Revenue Cutter Vigilant dated 1812, drafted and signed by William Ellery, as well as Capt. John Cahoone and ship builder Benjamin Marble.

Charting History Traveling Exhibit

- What is the name and location of your institution? *

- What dates are you interest in hosting for? [Note: the exhibit will be lent out for two month periods] *

- Which sections of the exhibit are you interested in using? Indigenous People (1 Panel) Conflict (4 Panels) Commerce (4 Panels) Conscience (4 Panels) All Panels

- Name * First Last

- Additional comments:

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

James Monroe

Fifth president 1817-1825.

- Grounds & Garden

- First Ladies

- VP Residence

- Historical Tour

- African-American History Month

- Presidents & Baseball

- Grounds and Garden

- Easter Egg Roll

- Christmas & Holidays

- State of the Union

- Historical Association

- Presidential Libraries

- Air Force One

Presidents by Name

Presidents by Date

View Flash Version

Papers of James Monroe

Inaugurating the Era of Good Feelings

James Monroe, Unknown artist (possibly Bass Otis) c. 1820 (James Monroe Museum)

By Cassandra Good, Associate Editor, Papers of James Monroe

On an unusually warm March afternoon two hundred years ago, James Monroe took the oath of office as America’s fifth president. In a capital city still recovering from having government buildings burned to the ground three years earlier by the British, large crowds thronged the city to celebrate Monroe’s inauguration on March 4, 1817. The planning of the ceremony itself caused a congressional squabble, the oath was taken under a temporary portico outside of a temporary capitol building, and nobody could hear Monroe’s speech. But that day ushered in a brief era of national unity and good feeling, when Americans formed (in Monroe’s words) “one great family with a common interest.”

James Monroe entered the presidency with more experience in elected or appointed office than any man before—or since. Born on Virginia’s Northern Neck in 1758, he had joined the Continental Army to fight in the Revolution as a teenager and been in public service almost continually since. As James Madison’s Secretary of State, he was seen as the natural successor to his long-time friend. He won election handily in 1816 against Federalist Rufus King, taking 84% of the electoral votes. It was a rare moment of near-unity after the bruising partisan bickering of the previous three decades, with the opposition Federalist party largely collapsing and power consolidating under Monroe’s Democratic Republicans.

Monroe planned, in keeping with tradition, a simple inauguration ceremony on the regular date of March 4. He wrote to both the Senate, which would host the inauguration, and Chief Justice Marshall, who would swear him in, of his plans on March 1. He stated that he would take the oath at noon in the chamber of the House of Representatives. A committee of senators then planned the specifics, determining where the president, leaders of the House and Senate, Supreme Court justices, heads of departments, and ambassadors would sit. The “fine red chairs” of the Senate chamber would be carried to the House chamber for the dignitaries. The audience would comprise senators at the front, behind them members of the House, and finally other selected men and women invited to attend. Officers would be appointed to keep the public from entering.

When the senators notified the House of Representatives of their plans, however, the representatives revolted. House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky wrote the senate committee mid-day on March 3, declaring that that the Senate “had not, as a body, a right to regulate the Hall of Representatives or to arrange the furniture thereof, or to introduce other furniture into it, without the concurrence of the House of Representatives.” In recalling the incident years later, Clay explained that he preferred the House chamber’s “plain democratic chairs” to the Senate’s fancier red seats. Apparently the two sides could not come to an agreement on room arrangements, and late that evening the Senate committee concluded they would hold the ceremony outside. The committee members sent a quick note to the diplomatic corps letting them know, which the ambassadors took to mean there would be no seats or formal role for them.

The next morning dawned with unseasonably warm temperatures and weather that was “extremely fine and exhilarating.” The sky was clear and the air still; as one attendee noted, “not an unruly breeze ruffled the plaits of the best handkerchief.” Vice President Daniel Tompkins arrived at the Monroes’ rented home at 2017 I St (several blocks from the White House), and the men left the house at 11:30 a.m. They were accompanied by a group of citizens on horseback, and they travelled down Pennsylvania Avenue to the temporary U.S. Capitol Building. Dubbed the Old Brick Capitol, the building stood across First Street (now the site of the Supreme Court) from the burned Capitol building and it housed the Senate and House from 1815 to 1819. Just before noon, Tompkins and Monroe entered the building with James Madison and the Supreme Court Justices for Tompkins’ swearing in in the Senate Chamber, as he was ceremonial leader of that body. Tompkins gave a short speech, and then the party moved outdoors for the day’s big event.

U.S. Capitol, George Munger, 1814 (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

The Old Brick Capitol (District of Columbia Public Library)

Outside of the building was a hastily-erected portico, with seats for the diplomatic corps to one side and the department heads on the other. The former sat empty, as the ambassadors did not know until afterward that there were in fact reserved seats for them and chose not to attend. Local military units were there, however, as was an audience of both ladies and gentlemen.

The crowd was gathered in carriages to watch the ceremony, but its size is hard to determine. A newspaper account noted that while it “was impossible to compute with any thing like accuracy the number of carriages, horses, and persons present,” the editors estimated five to eight thousand. “Such a concourse was never before seen in Washington,” they reported. Massachusetts senator Harrison Gray Otis’s wife, Sally Foster Otis, was less impressed with the crowd. She guessed that there were fewer attendees than at Boston’s Artillery Election Day (an annual parade and election of officers for the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company) and those at the inauguration “were by no means so well conditioned.”

Sally Foster Otis, Gilbert Stuart, 1809 (Reynolda House)

There were certainly enough people that “few if any heard” Monroe give his speech and take the oath of office. Even if Monroe spoke loudly, outdoors his voice could not have travelled far. But newspapers published his optimistic and celebratory speech in its entirety.