- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of home visit

Examples of home visit in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'home visit.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Dictionary Entries Near home visit

home visitor

Cite this Entry

“Home visit.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/home%20visit. Accessed 26 Mar. 2024.

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

8 grammar terms you used to know, but forgot, homophones, homographs, and homonyms, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 22, 12 words for signs of spring, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, fan favorites: your most liked words of the day 2023, games & quizzes.

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Home Visit: Opening the Doors for Family Health

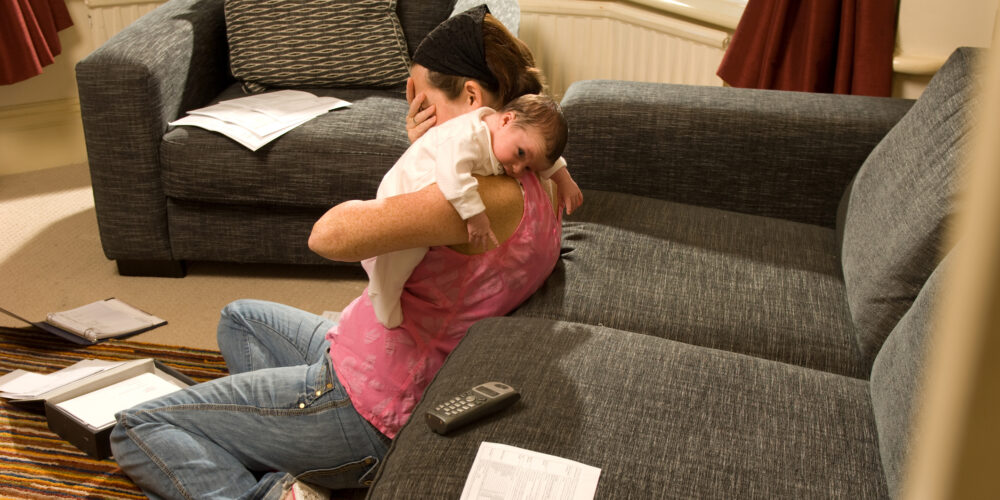

Chapter 11 Home Visit Opening the Doors for Family Health Claudia M. Smith Chapter Outline Home Visit Definition Purpose Advantages and Disadvantages Nurse–Family Relationships Principles of Nurse–Client Relationship with Family Phases of Relationships Characteristics of Relationships with Families Increasing Nurse–Family Relatedness Fostering a Caring Presence Creating Agreements for Relatedness Increasing Understanding through Communication Skills Reducing Potential Conflicts Matching the Nurse’s Expectations with Reality Clarifying Nursing Responsibilities Managing the Nurse’s Emotions Maintaining Flexibility in Response to Client Reactions Clarifying Confidentiality of Data Promoting Nurse Safety Clarifying the Nurse’s Self-Responsibility Promoting Safe Travel Handling Threats during Home Visits Protecting the Safety of Family Members Managing Time and Equipment Structuring Time Handling Emergencies Promoting Asepsis in the Home Modifying Equipment and Procedures in the Home Postvisit Activities Evaluating and Planning the Next Home Visit Consulting and Collaborating with the Team Making Referrals Legal Documentation The Future of Evidence-Based Home-Visiting Programs Focus Questions Why are home visits conducted? What are the advantages and disadvantages of home visits? How is the nurse–client relationship in a home similar to and different from nurse–client relationships in inpatient settings? How can a nurse’s family focus be maximized during a typical home visit? What promotes safety for community/public health nurses? What happens during a typical home visit? How can client participation be promoted? Key Terms Agreement Collaboration Consultation Empathy Family focus Genuineness Home visit Positive regard Presence Referral Nurses who work in all specialties and with all age groups can practice with a family focus , that is, thinking of the health of each family member and of the entire family per se and considering the effects of the interrelatedness of the family members on health. Because being family focused is a philosophy, it can be practiced in any setting. However, a family’s residence provides a special place for family-focused care. Community/public health nurses have historically sought to promote the well-being of families in the home setting ( Zerwekh, 1990 ). Community/public health nurses seek to promote health; prevent specific illnesses, injuries, and premature death; and reduce human suffering. Through home visits, community/ public health nurses provide opportunities for families to become aware of potential health problems, to receive anticipatory education, and to learn to mobilize resources for health promotion and primary prevention ( Kristjanson & Chalmers, 1991 ; Raatikainen, 1991 ). In clients’ homes, care can be personalized to a family’s coping strategies, problem-solving skills, and environmental resources (see Chapter 13 ). During home visits, community/public health nurses can uncover threats to health that are not evident when family members visit a physician’s office, health clinic, or emergency department ( Olds et al., 1995 ; Zerwekh, 1991 ). For example, during a visit in the home of a young mother, a nursing student observed a toddler playing with a paper cup full of tacks and putting them in his mouth. The student used the opportunity to discuss safety with the mother and persuaded her to keep the tacks on a high shelf. The quality of the home environment predicts the cognitive and social development of an infant ( Engelke & Engelke, 1992 ). Community/public health nurses successfully assist parents in improving relations with their children and in providing safe, stimulating physical environments. All levels of prevention can be addressed during home visits. Research has demonstrated that home visits by nurses during the prenatal and infancy periods prevent developmental and health problems ( Kitzman et al., 2000 ; Norr et al., 2003 ; Olds et al., 1986 ). Olds and colleagues demonstrated that families who received visits had fewer instances of child abuse and neglect, emergency department visits, accidents, and poisonings during the child’s first 2 years of life. These results were true for families of all socioeconomic levels but greater for low-income families. The health outcomes for families who received home visits were better than those of families that received care only in clinics or from private physicians. Furthermore, the favorable results were still apparent 15 years after the birth of the first child ( Olds et al., 1997 ), and the home visits reduced subsequent pregnancies ( Kitzman et al., 1997 ; Olds et al., 1997 ). The U.S. Advisory Board on Abuse and Neglect advocates such home-visiting programs as a means to prevent child abuse and neglect ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1990 ). Other research shows that home visits by nurses can reduce the incidence of drug-resistant tuberculosis and decrease preventable deaths among infected individuals ( Lewis & Chaisson, 1993 ). This goal is achieved through directly observing medication therapy in the individual’s home, workplace, or school on a daily basis or several times a week (see Chapter 8 ). Several factors have converged to expand opportunities for nursing care to adults and children with illnesses and disabilities in their homes. The American population has aged, chronic diseases are now the major illnesses among older persons, and attempts are being made to limit the rising hospital costs. As the average length of stay in hospitals has decreased since the early 1980s, families have had to care for more adults and children with acute illnesses in their homes. This increased demand for home health care has resulted in more agencies and nurses providing home care to the ill and teaching family members to perform the care (see Chapter 31 ). The degree to which families cope with a member with a chronic illness or disability significantly affects both the individual’s health status and the quality of life for the entire family ( Burns & Gianutsos, 1987 ; Harris, 1995 ; Whyte, 1992 ). Family members may be called on to support an individual family member’s adjustment to a chronic illness as well as take on tasks and roles that the ill member previously performed. This adjustment occurs over time and often takes place in the home. Community/public health nurses can assist families in making these adjustments. Since the late 1960s, deinstitutionalization of mentally ill clients has shifted them from inpatient psychiatric settings to their own homes, group homes, correctional facilities, and the streets (see Chapter 33 ). Nurses in the fields of community mental health and psychiatry began to include the relatives and surrogate family members in providing critical support to enable the person with a psychiatric diagnosis to live at home ( Mohit, 1996 ; Stolee et al., 1996 ). The hospice movement also recognizes the importance of a family focus during the process of a family member’s dying ( American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007a ). Care at home or in a homelike setting is cost effective under many circumstances. As the prevalence of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) increases and the number of older adults continues to increase, providing care in a cost-effective manner is both an ethical and an economic necessity. Nurses in any specialty can practice with a family focus. However, the specific goals and time constraints in each health care service setting affect the degree to which a family focus can be used. A home visit is one type of nurse–client encounter that facilitates a family focus. Home visiting does not guarantee a family focus. Rather, the setting itself and the structure of the encounter provide an opportunity for the nurse to practice with a family focus. A nurse visiting a client in his home listens to the man’s heart while his daughter looks on. Nurses who graduate from a baccalaureate nursing program are expected to have educational experiences that prepare them for beginning practice in community/public health nursing. Family-focused care is an essential element of community/public health nursing. One of the ways to improve the health of populations and communities is to improve the health of families ( ANA, 2007b ). Home visits may be made to any residence: apartments for older adults, group homes, boarding homes, dormitories, domiciliary care facilities, and shelters for the homeless, among others. In these residences, the family may not be related by blood, but, rather, they may be significant others: neighbors, friends, acquaintances, or paid caregivers. Nurses who are educated at the baccalaureate level are one of a few professional and service workers who are formally taught about making home visits. Some social work students, especially those interested in the fields of home health and protective services, also receive similar education. The American Red Cross and the National Home Caring Council have developed training programs for homemakers and home health aides; not all aides have received such extensive training, however. Agricultural and home economic extension workers in the United States and abroad also may make home visits ( Murray, 1968 ; World Health Organization, 1987 ). Home visit Definition A home visit is a purposeful interaction in a home (or residence) directed at promoting and maintaining the health of individuals and the family (or significant others). The service may include supporting a family during a member’s death. Just as a client’s visit to a clinic or outpatient service can be viewed as an encounter between health care professionals and the client, so can a home visit. A major distinction of a home visit is that the health care professional goes to the client rather than the client coming to the health care professional. Purpose Almost any health care service can be accomplished on a home visit. An assumption is that—except in an emergency—the client or family is sufficiently healthy to remain in the community and to manage health care after the nurse leaves the home. The foci of community/public health nursing practice in the home can be categorized under five basic goals: 1. Promoting support systems that are adequate and effective and encouraging use of health-related resources 2. Promoting adequate, effective care of a family member who has a specific problem related to illness or disability 3. Encouraging normal growth and development of family members and the family and educating the family about health promotion and illness prevention 4. Strengthening family functioning and relatedness 5. Promoting a healthful environment The five basic goals of community/public health nursing practice with families can be linked to categories of family problems ( Table 11-1 ). A pilot study to identify problems common in community/public health nursing practice settings revealed that problems clustered into four categories: (1) lifestyle and living resources, (2) current health status and deviations, (3) patterns and knowledge of health maintenance, and (4) family dynamics and structure ( Simmons, 1980 ). Home visits are one means by which community/public health nurses can address these problems and achieve goals for family health. Table 11-1 Family Health-Related Problems and Goals Problem * Goal Lifestyle and resources Promote support systems and use of health-related resources Health status deviations Promote adequate, effective family care of a member with an illness or disability Patterns and knowledge of health maintenance Encourage growth and development of family members, health promotion, and illness prevention Promote a healthful environment Family dynamics and structure Strengthen family functioning and relatedness * Problems from Simmons, D. (1980). A classification scheme for client problems in community health nursing (DHHS Pub No. HRA 8016). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Advantages and Disadvantages Advantages of home visits by nurses are numerous. Most of the disadvantages relate to expense and concerns about unpredictable environments ( Box 11-1 ). Box 11-1 Advantages and Disadvantages of Home Visiting Advantages • Home setting provides more opportunities for individualized care. • Most people prefer to receive care at home. • Environmental factors impinging on health, such as housing condition and finances, may be observed and considered more readily. • Collecting information and understanding lifestyle values are easier in family’s own environment. • Participation of family members is facilitated. • Individuals and family members may be more receptive to learning because they are less anxious in their own environments and because the immediacy of needing to know a particular fact or skill becomes more apparent. • Care to ill family members in the home can reduce overall costs by preventing hospitalizations and shortening the length of time spent in hospitals or other institutions. • A family focus is facilitated. Disadvantages • Travel time is costly. • Home visiting is less efficient for the nurse than working with groups or seeing many clients in an ambulatory site. • Distractions such as television and noisy children may be more difficult to control. • Clients may be resistant or fearful of the intimacy of home visits. • Nurse safety can be an issue. Nurse–family relationships How nurses are assigned to make home visits is both a philosophical and a management issue. Some community/public health nurses are assigned by geographical area or district . The size of the geographical area for home visits varies with the population density. In a densely populated urban area, a nurse might visit in one neighborhood; in a less densely populated area, the nurse might be assigned to visit in an entire county. With geographical assignments, the nurse has the potential to work with the entire population in a district and to handle a broad range of health concerns; the nurse can also become well acquainted with the community’s health and social resources. The potential for a family-focused approach is strengthened because the nurse’s concerns consist of all health issues identified with a specific family or group of families. The nurse remains a clinical generalist, working with people of all ages. Other community/public health nurses are assigned to work with a population aggregate in one or more geopolitical communities. For example, a nurse may work for a categorical program that addresses family planning or adolescent pregnancy, in which case the nurse would visit only families to which the category applies. This type of assignment allows a nurse to work predominantly with a specific interest area (e.g., family planning and pregnancy) or with a specific aggregate (e.g., families with fertile women). Principles of Nurse–Client Relationship with Family Regardless of whether the community/public health nurse is assigned to work with an aggregate or the entire population, several principles strengthen the clarity of purpose: • By definition, the nurse focuses on the family. • The health focus can be on the entire spectrum of health needs and all three levels of prevention. • The family retains autonomy in health-related decisions. • The nurse is a guest in the family’s home. Family Focus To relate to the family, the community/public health nurse does not have to meet all members of the household personally, although varying the times of visits might allow the nurse to meet family members usually at work or school. Relating to the family requires that the nurse be concerned about the health of each member and about each person’s contribution to the functioning of the family. One family member may be the primary informant; in such instances, the nurse should realize that the information received is being filtered by the person’s perceptions. The community/public health nurse should take the time to introduce herself or himself to each person present and address each person by name. Building trust is an essential foundation for a continued relationship ( Heaman et al., 2007 ; McNaughton, 2000 ; Zerwekh, 1992 ). The nurse should use the clients’ surnames unless they introduce themselves in another way or give permission for the nurse to be less formal. Interacting with as many family members as possible, identifying the family member most responsible for health issues, and acknowledging the family member with the most authority are important. The nurse should ask for an introduction to pets and ask for permission before picking up infants and children unless it is granted nonverbally. A nurse enters the home of a client with a young child. All Levels of Prevention Through assessment, the community/public health nurse attempts to identify what actual and potential problems or concerns exist with each individual and, thematically, within the family (see Chapter 13 ). Issues of health promotion (diet) and specific protection (immunization) may exist, as may undiagnosed medical problems for which referral is necessary for further diagnosis and treatment. Home visits also can be effective in stimulating family members to seek appropriate services such as prenatal care ( Bradley & Martin, 1994 ) and immunizations ( Norr et al., 2003 ). Actual family problems in coping with illness or disability may require direct intervention. Preventing sequelae and maximizing potential may be appropriate for families with a chronically ill member. Health-related problems may appear predominantly in one family member or among several members. A thematic family problem might be related to nutrition. For example, a mother may be anemic, a preschooler may be obese, and a father may not follow a low-fat diet for hypertension. Family Autonomy A few circumstances exist in our society in which the health of the community, or public, is considered to have priority over the right of individual persons or families to do as they wish. In most states, statutes (laws) provide that health care workers, including community/public health nurses, have a right and an obligation to intervene in cases of family abuse and neglect, potential suicide or homicide, and existence of communicable diseases that pose a threat of infection to others. Except for these three basic categories, the family retains the ultimate authority for health-related decisions and actions . In the home setting, family members participate more in their own care. Nursing care in the home is intermittent, not 24 hours a day. When the visit ends, the family takes responsibility for their own health, albeit with varying degrees of interest, commitment, knowledge, and skill. This role is often difficult for beginning community/public health nurses to accept; learning to distinguish the family’s responsibilities from the nurse’s responsibilities involves experience and consideration of laws and ethics. Except in crises, taking over for the family in areas in which they have demonstrated capability is usually inappropriate. For example, if family members typically call the pharmacy to renew medications and make their own medical appointments, beginning to do these things for them is inappropriate for the nurse. Taking over undermines self-esteem, confidence, and success. Nurse as Guest Being a guest as a community/public health nurse in a family’s home does not mean that the relationship is social. The social graces for the community and culture of the family must be considered so that the family is at ease and is not offended. However, the relationship is intended to be therapeutic. For example, many older persons believe that offering something to eat or drink is important as a sign that they are being courteous and hospitable. Because your refusal to share in a glass of iced tea may be taken as an affront, you may opt to accept the tea. However, you certainly have the right to refuse, especially if infectious disease is a concern. Validate with the client that the time of the visit is convenient. If the client fails to offer you a seat, you may ask if there is a place for you and the family to sit and talk. This place may be any room of the house or even outside in good weather. Phases of Relationships Relatedness and communication between the nurse and the client are fundamental to all nursing care. A nurse–client relationship with a family (rather than an individual) is critical to community/public health nursing. The phases of the nurse–client relationship with a family are the same as are those with an individual. Different schemes have been developed for naming phases of relationships. All schemes have (1) a preinitiation or preplanning phase, (2) an initiation or introductory phase, (3) a working phase, and (4) an ending phase (Arnold & Boggs, 2011). Some schemes distinguish a power and control or contractual phase that occurs before the working phase. The initiation phase may take several visits. During this phase, the nurse and the family get to know one another and determine how the family health problems are mutually defined. The more experience the nurse has, the more efficient she or he will become; initially, many community/public health nursing students may require four to six visits to feel comfortable and to clarify their role ( Barton & Brown, 1995 ). The nursing student should keep in mind that the relationship with the family usually involves many encounters over time—home visits, telephone calls, or visits at other ambulatory sites such as clinics. Several encounters may occur during each phase of the relationship ( Figure 11-1 ). Each encounter also has its own phases ( Figure 11-2 ). Figure 11-1 A series of encounters during a relationship. (Redrawn from Smith, C. [1980]. A series of encounters during a relationship [Unpublished manuscript]. Baltimore, MD: University of Maryland School of Nursing.) Figure 11-2 Phases of a home visit. (Redrawn from Smith, C. [1980]. Phases of a home visit [Unpublished manuscript]. Baltimore, MD: University of Maryland School of Nursing.) Preplanning each telephone call and home visit is helpful. Box 11-2 lists activities in which community/public health nurses usually engage before a home visit. The list can be used as a guide in helping novice community/public health nurses organize previsit activities efficiently. Box 11-2 Planning Before a Home Visit 1. Have name, address, and telephone number of the family, with directions and a map. 2. Have telephone number of agency by which supervisor or faculty can be reached. 3. Have emergency telephone numbers for police, fire, and emergency medical services (EMS) personnel. 4. Clarify who has referred the family to you and why. 5. Consider what is usually expected of a nurse in working with a family that has been referred for these health concerns (e.g., postpartum visit), and clarify the purposes of this home visit. 6. Consider whether any special safety precautions are required. 7. Have a plan of activities for the home visit time (see Box 11-3 ). 8. Have equipment needed for hand-washing, physical assessment, and direct care interventions, or verify that client has the equipment in the home. 9. Take any data assessment or permission forms that are needed. 10. Have information and teaching aids for health teaching, as appropriate. 11. Have information about community resources, as appropriate. 12. Have gasoline in your automobile or money for public transportation. 13. Leave an itinerary with the agency personnel or faculty. 14. Approach the visit with self-confidence and caring. The visit begins with a reintroduction and a review of the plan for the day; the nurse must assess what has happened with the family since the last encounter. At this point, the nurse may renegotiate the plan for the visit and implement it. The end of the visit consists of summarizing, preparing for the next encounter, and leave-taking. Box 11-3 describes the community/public health nurse’s typical activities during a home visit. Box 11-3 Nursing Activities During Three Phases of a Home Visit Initiation Phase of Home Visit 1. Knock on door, and stand where you can be observed if a peephole or window exists. 2. Identify self as [name], the nurse from [name of agency]. 3. Ask for the person to whom you were referred or the person with whom the appointment was made. 4. Observe environment with regard to your own safety. 5. Introduce yourself to persons who are present and acknowledge them. 6. Sit where family directs you to sit. 7. Discuss purpose of visit. On initial visits, discuss services to be provided by agency. 8. Have permission forms signed to initiate services. This activity may be done later in the home visit if more explanation of services is needed for the family to understand what is being offered. Implementation Phase of Home Visit 9. Complete health assessment database for the individual client. 10. On return visits, assess for changes since the last encounter. Explore the degree that family was able to follow up on plans from previous visit. Explore barriers if follow-up did not occur. 11. Wash hands before and after conducting any physical assessment and direct physical care. 12. Conduct physical assessment, as appropriate, and perform direct physical care. 13. Identify household members and their health needs, use of community resources, and environmental hazards. 14. Explore values, preferences, and clients’ perceptions of needs and concerns. 15. Conduct health teaching as appropriate, and provide written instructions. Include any safety recommendations. 16. Discuss any referral, collaboration, or consultation that you recommend. 17. Provide comfort and counseling, as needed. Termination Phase of Home Visit 18. Summarize accomplishments of visit. 19. Clarify family’s plan of care related to potential health emergency appropriate to health problems. 20. Discuss plan for next home visit and discuss activities to be accomplished in the interim by the community/public health nurse, individual client, and family members. 21. Leave written identification of yourself and agency, with telephone numbers. Characteristics of Relationships with Families Some differences are worth discussing in nurses’ relationships with families compared with those with individual clients in hospitals. The difference that usually seems most significant to the nurse who is learning to make home visits is the fact that the nurse has less control over the family’s environment and health-related behavior ( McNaughton, 2000 ). The relationship usually extends for a longer period. A more interdependent relationship develops between the community/public health nurse and the family throughout all steps of the nursing process. Families Retain Much Control The family can control the nurse’s entry into the home by explicitly refusing assistance, establishing the time of the visit, or deciding whether to answer the door. Unlike hospitalized clients, family members can just walk away and not be home for the visit. One study of home visits to high-risk pregnant women revealed that younger and more financially distressed women tended to miss more appointments for home visits ( Josten et al., 1995 ). Being rejected by the family is often a concern of nurses who are learning to conduct home visits. As with any relationship, anxiety can exist in relation to meeting new, unknown families. Families may actually have similar feelings about meeting the nurse and may wonder what the nurse will think of them, their lifestyle, and their health care behavior. A helpful practice is to keep your perspective; if the clients are home for your visit, they are at least ambivalent about the meeting! If they are at home to answer the door, they are willing to consider what you have to offer. Most families involved with home care of the ill have requested assistance. Because only a few circumstances exist (as previously discussed) in which nursing care can be forced on families, the nurse can view the home visit as an opportunity to explore voluntarily the possibility of engaging in relationships ( Byrd, 1995 ). The nurse is there to offer services and engage the family in a dialogue about health concerns, barriers, and goals. As with all nurse–client relationships, the nurse’s commitment, authenticity, and caring constitute the art of nursing practice that can make a difference in the lives of families. Just as not all individuals in the hospital are ready or able to use all of the suggestions made to them, families have varying degrees of openness to change. If after discussing the possibilities the family declines either overtly or through its actions, the nurse has provided an opportunity for informed decision making and has no further obligation. Goals of Nursing Care Are Long Term A second major difference in nurse relationships with families is that the goals are usually more long term than are those with individual clients in hospitals. Clients may be in hospice programs for 6 months. A family with a member who has a recent diagnosis of hypertension may take 6 weeks to adjust to medications, diet, and other lifestyle changes. A school-aged child with a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder may take as long as half the school year to show improvement in behavior and learning; sometimes, a year may be required for appropriate classroom placement. For some nurses, this time frame is judged to be slow and tedious. For others, the time frame is seen as an opportunity to know a family in more depth, share life experiences over time, and see results of modifications in nursing care. For nurses who like to know about a broad range of health and nursing issues, relationships with families stimulate this interest. Having had some experience in home visiting is helpful for nurses who work in inpatient settings; it allows them to appreciate the scope and depth of practice of community/public health nurses who make home visits as a part of their regular practice. These experiences can sensitize hospital nurses to the home environments of their clients and can result in better hospital discharge plans and referrals. Because ultimate goals may take a long time to achieve, short-term objectives must be developed to achieve long-term goals. For example, a family needs to be able to plan lower-calorie menus with sufficient nutrients before weight loss is possible; a parent may need to spend time with a child daily before unruly behavior improves. Nursing interventions in a hospital setting become short-term objectives for client learning and mastery in the home setting. In an inpatient setting, giving medications as prescribed is a nursing action. In the home, the spouse giving medications as prescribed becomes a behavioral objective for the family; the related nursing action is teaching. Human progress toward any goal does not usually occur at a steady pace. For example, you may start out bicycling faithfully three times a week and give up abruptly. Similarly, clients may skip an insulin dose or an oral contraceptive. A family may assertively call appropriate community agencies, keep appointments, and stop abruptly. Families can be committed to their own health and well-being and yet not act on their commitment consistently. Recognizing that setbacks and discouragement are a part of life allows the community/public health nurse to be more accepting of reality and have the objectivity to renegotiate goals and plans with families. Box 11-4 includes evidence-based ways to foster goal accomplishment. Box 11-4 Best Practices in Fostering Goal Accomplishment With Families 1. Share goals explicitly with family. 2. Divide goals into manageable steps. 3. Teach the family members to care for themselves. 4. Do not expect the family to do something all of the time or perfectly. 5. Be satisfied with small, subtle changes. 6. Be flexible. Changes are sometimes subtle or small. Success breeds success, at least motivationally. The short-term goals on which everyone has agreed are important to make clear so that the nurse and the family members have a common basis for evaluation. Goals can be set in a logical sequence, in small steps, to increase the chance of success. In an inpatient setting, the skilled nurse notices the subtle changes in client behavior and health status that can warn of further disequilibrium or can signal improvement. Similarly, during a series of home visits, the skilled nurse is aware of slight variations in home management, personal care, and memory that may presage a deteriorating biological or social condition. Nursing Care Is More Interdependent with Families Because families have more control over their health in their own homes and because change is usually gradual, greater emphasis must be placed on mutual goals if the nurse and family are to achieve long-term success. Except in emergency situations, the client determines the priority of issues. A parent may be adamant that obtaining food is more important than obtaining their child’s immunization. A child’s school performance may be of greater concern to a mother than is her own abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) smear results. Failure of the nurse to address the family’s primary priority may result in the family perceiving that the nurse does not genuinely care. At times, the priority problem is not directly health related, or the solution to a health problem can be handled better by another agency or discipline. In these instances, the empathic nurse can address the family’s stress level, problem-solving ability, and support systems and make appropriate referrals. When the nurse takes time to validate and discuss the primary concern, the relationship is enhanced. Families are sometimes unaware of what they do not know. The nurse must suggest health-related topics that are appropriate for the family situation. For example, a young mother with a healthy newborn may not have thought about how to determine when her baby is ill. A spouse caring for his wife with Alzheimer disease may not know what safety precautions are necessary. Community/public health nurses seek to enhance family competence by sharing their professional knowledge with families and building on the family’s experience ( Reutter & Ford, 1997 ; SmithBattle, 2009 ). Flexibility is a key. Because visits occur over several days to months, other events (e.g., episodic illnesses, a neighbor’s death, community unemployment) can impinge on the original plan. Family members may be rehospitalized and receive totally new medical orders once they are discharged to home. The nurse’s clarity of purpose is essential in identifying and negotiating other health-related priorities after the first concerns have been addressed ( Monsen, Radosevich, Kerr, & Fulkerson, 2011 ). Increasing nurse–family relatedness What promotes a successful home visit? What aspects of the nurse’s presence promote relatedness? What structures provide direction and flexibility? The nursing process provides a general structure, and communication is a primary vehicle through which the nursing process is manifested. The foundation for both the nursing process and communication is relatedness and caring ( ANA, 2003 ; McNaughton, 2005 ; Roach, 1997 ; SmithBattle, 2009 ; Watson, 2002 ; Watson, 2005 ). Fostering a Caring Presence Nursing efforts are not always successful. However, by being concerned about the impact of home visits on the family and by asking questions regarding her or his own motivations, the nurse automatically increases the likelihood that home visits will be of benefit to the family. The nurse is acknowledging that the intention is for the relationship to be meaningful to both the nurse and the family. Building and preserving relationships is a central focus of home visiting and requires significant effort ( Heaman et al., 2007 ; McNaughton, 2000 , 2005 ). The relatedness of nurses in community health with clients is important ( Goldsborough, 1969 ; SmithBattle, 2009 ; Zerwekh, 1992 ). Involvement, essentially, is caring deeply about what is happening and what might happen to a person, then doing something with and for that person. It is reaching out and touching and hearing the inner being of another…. For a nurse–client relationship to become a moving force toward action, the nurse must go beyond obvious nursing needs and try to know the client as a person and include him in planning his nursing care. This means sharing feelings, ideas, beliefs and values with the client…. Without responsibility and commitment to oneself and others…[a person] only exists. It is through interaction and meaningful involvement with others that we move into being human ( Goldsborough, 1969 , pp. 66-68). Mayers (1973, p. 331) observed 16 randomly selected nurses during home visits to 37 families and reported that “regardless of the specific interaction style [of each nurse], the clients of nurses who were client-focused consistently tended to respond with interest, involvement and mutuality.” A client-focused nurse was observed as one who followed client cues, attempted to understand the client’s view of the situation, and included the client in generating solutions. Being related is a contribution that the nurse can make to the family, independent of specific information and technical skills, a contribution that students often underestimate. Although being related is necessary, it is inadequate in itself for high-quality nursing. A community/public health nurse must also be competent. Community/public health nursing also depends on assessment skills, judgment, teaching skills, safe technical skills, and the ability to provide accurate information. As a community/public health nurse’s practice evolves, tension always exists between being related and doing the tasks. In each situation, an opportunity exists to ask, “How can I express my caring and do (perform direct care, teach, refer) what is needed?” Barrett (1982) and Katzman and colleagues (1987) reported on the differences that students actually make in the lives of families. Barrett (1982) demonstrated that postpartum home visits by nursing students reduced costly postpartum emergency department and hospital visits. Katzman and co-workers (1987) considered hundreds of visits per semester made by 80 students in a southwestern state to families with newborns, well children, pregnant women, and members with chronic illnesses. Case examples describe how student enthusiasm and involvement contributed to specific health results. Everything a nurse has learned about relationships is important to recall and transfer to the experience of home visiting. Carl Rogers (1969) identified three characteristics of a helping relationship: positive regard, empathy, and genuineness. These characteristics are relevant in all nurse–client relationships, and they are especially important when relationships are initiated and developed in the less-structured home setting. Presence means being related interpersonally in ways that reveal positive regard, empathy, genuineness, and caring concern. How is it possible to accept a client who keeps a disorderly house or who keeps such a clean house that you feel as if you are contaminating it by being there? How is it possible to have positive feelings about an unmarried mother of three when you and your partner have successfully avoided pregnancy? Having positive regard for a family does not mean giving up your own values and behavior (see Chapter 10 ). Having positive regard for a family that lives differently from the way you do does not mean you need to ignore your past experiences. The latter is impossible. Rather, having positive regard means having the ability to distinguish between the person and her or his behavior. Saying to yourself, “This is a person who keeps a messy house” is different from saying, “This person is a mess!” Positive regard involves recognizing the value of persons because they are human beings. Accept the family, not necessarily the family’s behavior. All behavior is purposeful; and without further information, you cannot determine the meaning of a particular family behavior. Positive regard involves looking for the common human experiences. For example, it is likely that both you and client family members experience awe in the behavior of a newborn and sadness in the face of loss. Empathy is the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and to be able to walk in her or his footsteps so as to understand her or his journey. “Empathy requires sensitivity to another’s experience…including sensing, understanding, and sharing the feelings and needs of the other person, seeing things from the other’s perspective” according to Rogers (cited in Gary & Kavanagh, 1991 , p. 89). Empathy goes beyond self and identity to acknowledge the essence of all persons. It links a characteristic of a helping relationship with spirituality or “a sense of connection to life itself” ( Haber et al., 1987 , p. 78). Empathy is a necessary pathway for our relatedness. However, what does understanding another person’s experience mean? More than emotions are involved. A person’s experience includes the sense that she or he makes of aspects of human existence ( SmithBattle, 2009 ; van Manen, 1990 ). Being understood means that a person is no longer alone ( Arnold, 1996 ). Being understood provides support in the face of stress, illness, disability, pain, grief, and suffering. When a client feels understood in a nurse–client partnership (side-by-side relationship), the client’s experience of being cared for is enhanced ( Beck, 1992 ). To understand another person’s experience, you must be able to imagine being in her or his place, recognize commonalities among persons, and have a secure sense of yourself ( Davis, 1990 ). Being aware of your own values and boundaries is helpful in retaining your identity in your interactions with others. To understand another individual’s experience, you must also be willing to engage in conversation to negotiate mutual definitions of the situation. For example, if you are excited that an older person is recovering function after a stroke, but the person’s spouse sees only the loss of an active travel companion, a mutual definition of the situation does not exist. Empathy will not occur unless you can also understand the spouse’s perspective. As human beings, we all like to perceive that we have some control in our environment, that we have some choice. We avoid being dominated and conned. The nurse’s genuineness facilitates honesty and disclosure, reduces the likelihood that the family will feel betrayed or coerced, and enhances the relationship. Genuineness does not mean that you speak everything that you think. Genuineness means that what you say and do is consistent with your understanding of the situation. The nurse can promote genuine self-expression in others by creating an atmosphere of trust, accepting that each person has a right to self-expression, “actively seeking to understand” others, and assisting them to become aware of and understand themselves ( Goldsborough, 1969 , p. 66). When family members do not believe that being genuine with the nurse is safe, they may tell only what they think the nurse would like to hear. This action makes developing a mutual plan of care much more difficult. The reciprocal side of genuineness is being willing to undertake a journey of self-expression, self-understanding, and growth. Tamara, a recent nursing graduate, wrote about her growing self-responsibility: “Although I felt out of control, I felt very responsible. I took pride in knowing that these families were my families, and I was responsible for their care. I was responsible for their health teaching. This was the first semester where there was no a faculty member around all day long. I feel that this will help me so much as I begin my nursing career. I have truly felt independent and completely responsible for my actions in this clinical experience.” This student, who preferred predictable environments, was able to confront her anxiety and anger in environments in which much was beyond her control. A mother was not interested in the student’s priorities. A family abruptly moved out of the state in the middle of the semester. Nonetheless, the student was able to respond in such circumstances. She became more responsible, and she was able to temper her judgment and work with the mother’s concern. When the family moved, the student experienced frustration and anger that she would not see the “fruits of her labor” and that she would “have to start over” with another family. However, her ability to respond increased because of her commitment to her own growth, relatedness with families, and desire to contribute to the health and well-being of others. In a context of relating with and advocating for the family, the relationship becomes an opportunity for growth in both the nurse’s and the family’s lives ( Glugover, 1987 ). Imagine standing side-by-side with the family, being concerned for their well-being and growth. Now imagine talking to a family face-to-face, attempting to have them do things your way. The first image is a more caring and empathic one. Creating Agreements for Relatedness How can communications be structured to increase the participation of family members? Without the family’s engagement, the community/public health nurse will have few positive effects on the health behavior and health status of the family and its members. Nurses are expert in caring for the ill; in knowing about ways to cope with illness, to promote health, and to protect against specific diseases; and in teaching and supporting family members. Family members are experts in their own health. They know the family health history, they experience their health states, and they are aware of their health-related concerns. Through the nurse–family relationship, a fluid process takes place of matching the family’s perceived needs with the nurse’s perceptions and professional judgments about the family’s needs. Paradoxically, the more skilled the nurse is in forgetting her or his own anxiety about being the good nurse, the more likely the nurse is to listen to the family members, validate their reality, and negotiate an adequate, effective plan of care. One study of home visits revealed that more than half of the goals stated by public health nurses to the researcher could not be detected, even implicitly, during observations of the home visits. Therefore, half the goals were known only to the nurse and were, therefore, not mutual. The more specifically and concretely the goals were stated by the nurse to the researcher, the greater would be the likelihood that the clients understood the nurse’s purposes ( Mayers, 1973 ). To negotiate mutual goals, the client needs to understand the nurse’s purposes. The initial letter, telephone call, or home visit is the time to share your ideas with the family about why you are contacting them. During the first interpersonal encounter by telephone or home visit, explore the family members’ ideas about the purpose of your visits. This phase is essential in establishing a mutually agreed on basis for a series of encounters. As a result of her qualitative research study of maternal-child home visiting, Byrd (2006, p. 271) stated that “people enter…relationships with the expectation of receiving a benefit” that may be information, status, service, or goods. Byrd asserted that it is important for nurses to create client expectations through previsit publicity about (marketing) home-visiting programs. Also it is essential to understand the expectations of the specific persons being visited. Family members may have had previous relationships with community/public health nurses and students. Family members may be able to share such information as what they found to be most helpful, why they are willing to work with a nurse or student again, and what goals they have in mind. Other families who have had no prior experience with community/public health nurses may not have specific expectations. Asking is important. A contract is a specific, structured agreement regarding the process and conditions by which a health-related goal will be sought. In the beginning of most student learning experiences, the agreement usually entails one or more family members continuing to meet with the nursing student for a specific number of visits or weeks. Initially, specific goals and the nurse’s role regarding health promotion and illness prevention may be unclear. (If this role was already clear, undergoing a period of study and orientation would be unnecessary.) Initially, the agreement may be as simple as, “We will meet here at your house next Tuesday at 11:00 AM until around noon to continue to discuss what I can offer related to your family’s health and what you’d like. We can get to know each other better. We can talk more about how the week has gone for you and your family with your new baby.” These statements are the nurse’s oral offer to meet under specific conditions of time and place. The process of mutual discussion is mentioned. The goals remain general and implicit: fostering the family’s developmental task of incorporating an infant and fostering family–nurse relatedness. For the next week’s contract to be complete, the family member or members would have to agree. The most important element initially is whether agreement about being present at a specific time and place can be reached. If 11:00 AM is not workable for the family, would another time during the day when you both are available be mutually agreeable? For families who do not focus as much on the future, a community/public health nurse needs to be more flexible in scheduling the time of each visit. The word contract often implies legally binding agreements. This is not true of nurse–client contracts. Nurses are legally and ethically bound to keep their word in relation to nursing care; clients are not legally bound to keep their agreements. However, establishing a mutual agreement for relating increases the clarity of who will do what, when, where, for what purposes, and under what conditions. Because of some people’s negative response to the word contract, agreement or discussion of responsibilities may be better. An agreement may be oral or written. For some families, written agreements, especially early in the relationship, may be perceived as a threat. For example, a family that has been conned by a household repair scheme may be very suspicious of written agreements. Family members who are not legal citizens may not want to sign an agreement for fear that if it is not kept they will be punished. Do not push for a written agreement if the family is uncomfortable. If you do notice such discomfort, this may be a good opportunity to explore their fears. Written agreements are required when insurance is paying for the care provided by nurses working with home health agencies and to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Helgeson and Berg (1985) describe factors affecting the contracting process by studying a small convenience sample of 15 community/public health nursing students and 12 client responses. Of the 11 students who introduced the idea of a contract to clients, all did so between the second and the fourth visits of a 16-week series of visits; 9 students did so orally rather than in writing. No specific time was the best. Eight clients were very receptive to the idea because they liked the idea of establishing goals to work toward and felt the contract would serve as a reminder of their responsibility. The very process of developing a draft agreement to present to families provides the novice practitioner with an increased focus of care, clarity of nurse and family responsibilities and activities, and a basis from which to negotiate modifications in client behaviors ( Helgeson & Berg, 1985 ; Sheridan & Smith, 1975 ). The Home Visiting Evaluation Tool in Figure 11-3 lists nurse behaviors that are appropriate for home visits, especially initial home visits and those early in a series of home visits. Nurses can use this list as a preplanning tool to identify their readiness to conduct a specific home visit. Additionally, students and community/public health nurses have used the tool to evaluate initial home visits and identify their behaviors that were omitted and needed to be included on the second home visits. The tool also has been used jointly as an evaluation tool by nurses and supervisors and students and faculty. Figure 11-3 Home Visiting Evaluation Tool. (From Chichester, M., & Smith, C. [1980]. Home visiting evaluation tool [Unpublished manuscript]. Baltimore, MD: University of Maryland School of Nursing.)

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Home Health Care

- Health Promotion and Risk Reduction in the Community

- Disaster Management: Caring for Communities in an Emergency

- Financing of Health Care: Context for Community/Public Health Nursing

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Why Home Visiting?

The evidence base for home visiting, including its cost effectiveness, is strong and growing. Below are examples of home visiting's demonstrated impact on critical needs and why home visiting is a key service strategy for improving infant, maternal, and family outcomes.

Home visiting has measurable benefits.

By meeting families where they are, home visiting programs have demonstrated short- and long-term impacts on the health, safety, and school-readiness of children; maternal health; and family stability and financial security. Home visitors are able to meet with families in their home and provide culturally competent, individualized needs assessments and services. This results in measured improvements in the following outcomes:

Healthy Babies

Home visitors work with expectant mothers to access prenatal care and engage in healthy behaviors during and after pregnancy. For example—

- Pregnant participants are more likely to access prenatal care and carry their babies to term.

- Home visiting promotes infant caregiving practices like breastfeeding, which has been associated with positive long-term outcomes related to cognitive development and child health.

Safe Homes and Nurturing Relationships

Home visitors provide caregivers with knowledge and training to reduce the risk of unintended injuries. For example—

- Home visitors teach caregivers how to “baby proof” their home to prevent accidents that can lead to emergency room visits, disabilities, or even death.

- They also teach caregivers how to engage with children in positive, nurturing ways, thus reducing child maltreatment .

Optimal Early Learning and Long-Term Academic Achievement

Home visitors offer caregivers timely information about child development and the importance of early childhood in establishing the building blocks for life. For example—

- They help caregivers recognize the value of reading and other activities for early learning. This guidance translates to improvements in children’s early language and cognitive development, as well as academic achievements in grades 1 through 3 .

Supported Families

Home visitors make referrals and coordinate services for children and caregivers, including job training and education programs, early care and education services, and— if needed—mental health and domestic violence resources. Research shows that—

- Compared with their counterparts, caregivers enrolled in home visiting have higher monthly incomes, are more likely to be enrolled in school , and are more likely to be employed .

Home visiting is cost effective.

Studies have found a return on investment of $1.80 to $5.70 for every dollar spent on home visiting. This strong return on investment is consistent with established research on other types of early childhood interventions.

Learn more in our Primer and annual Yearbook .

Stay up to date on the latest home visiting information.

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

History and Development of Home Visiting in the United States

Social justice movements before 1950, the war on poverty and prevention of child maltreatment, expansion of home visiting in recent decades, home visiting outside the united states, poverty, child health, and home visiting, national evaluation and evidence of effectiveness, home visiting and the medical home, recommendations and position statement, community pediatricians, large health systems, managed care organizations, and accountable care organizations, researchers, the aap endorses and promotes the following general policy positions and advocacy strategies:, conclusions.

- Lead Authors

- Council on community Pediatrics Executive Committee, 2016–2017

- Council on Early Childhood Executive Committee, 2016–2017

- Committee on Child abuse and Neglect, 2016–2017

Early Childhood Home Visiting

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

James H. Duffee , Alan L. Mendelsohn , Alice A. Kuo , Lori A. Legano , Marian F. Earls , COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS , COUNCIL ON EARLY CHILDHOOD , COMMITTEE ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT , Lance A. Chilton , Patricia J. Flanagan , Kimberley J. Dilley , Andrea E. Green , J. Raul Gutierrez , Virginia A. Keane , Scott D. Krugman , Julie M. Linton , Carla D. McKelvey , Jacqueline L. Nelson , Emalee G. Flaherty , Amy R. Gavril , Sheila M. Idzerda , Antoinette “Toni” Laskey , John M. Leventhal , Jill M. Sells , Elaine Donoghue , Andrew Hashikawa , Terri McFadden , Georgina Peacock , Seth Scholer , Jennifer Takagishi , Douglas Vanderbilt , Patricia G. Williams; Early Childhood Home Visiting. Pediatrics September 2017; 140 (3): e20172150. 10.1542/peds.2017-2150

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

High-quality home-visiting services for infants and young children can improve family relationships, advance school readiness, reduce child maltreatment, improve maternal-infant health outcomes, and increase family economic self-sufficiency. The American Academy of Pediatrics supports unwavering federal funding of state home-visiting initiatives, the expansion of evidence-based programs, and a robust, coordinated national evaluation designed to confirm best practices and cost-efficiency. Community home visiting is most effective as a component of a comprehensive early childhood system that actively includes and enhances a family-centered medical home.

Recent advances in program design, evaluation, and funding have stimulated widespread implementation of public health programs that use home visiting as a central service. This policy statement is an update of “The Role of Preschool Home-Visiting Programs in Improving Children’s Developmental and Health Outcomes” (2009) and summarizes salient changes, emphasizes practical recommendations for community pediatricians, and outlines important national priorities intended to improve the health and safety of children, families, and communities. 1 By promoting child development, early literacy, school readiness, informed parenting, and family self-sufficiency, home visiting presents a valuable strategy to buffer the effects of poverty and adverse early childhood experiences that influence lifelong health.

The term “home visiting” refers to an evidence-based strategy in which a professional or paraprofessional renders a service in a community or private home setting. Home visiting also refers to the variety of programs that employ home visitors as a central component of a comprehensive service plan. 2 Early childhood home-visiting programs may be focused on young children, children with special health care needs, parents of young children, or the relationship between children and parents, and they can use a 2-generational strategy to simultaneously address parental and family social and economic challenges. 3

Home-visiting programs vary widely with regard to target populations and goals. Many successful home-visiting models are directed toward mothers and infants in high-risk groups, such as adolescent mothers and single-parent families. Other models concentrate on specific populations, such as recently incarcerated adolescents, children with special needs, or immigrants. Some programs are designed to identify risk factors, such as environmental hazards and maternal mental health, but others include mentoring, coaching, and other therapeutic interventions. Many employ independently licensed health professionals, but others depend on trained paraprofessionals (including community health workers) drawn from the communities they serve. Community-based care coordination (including housing, transportation, and nutritional support) often are service components. Integration with the family-centered medical home (FCMH) has been a recent focus for program improvement and medical education. 4

Home visiting began in the United States in the 1880s as an activity of each of 3 social justice movements. Derived from the British models developed a few decades earlier, home visitors were deployed to promote universal kindergarten, improve maternal-infant health through public health nursing, and support impoverished immigrant communities as part of the philanthropic settlement house movement. From the late 19th through the early 20th century, teachers and public health nurses visited communities and families to provide in-home education and health care to urban women and children. These efforts were based on the assumptions still held that education is the most powerful strategy to lift children out of poverty and that the lifelong health of families in immigrant and poor neighborhoods is improved by addressing the social and economic aspects of health and disease. 5

From the Great Depression through World War II, funding for social initiatives decreased and philanthropic support for home visitors declined. After the relatively prosperous postwar period, renewed interest developed in antipoverty activities, including home visiting, especially in the context of the Civil Rights Movement. In the 1960s, home visiting became an important component of the government’s so-called War on Poverty. Home visiting was and remains integral to programs such as Head Start, although it is applied on a limited basis compared with Early Head Start, for which home visiting is a central service component. A decade later, many home-visiting programs shifted to include case management, intending to help families achieve self-sufficiency and link them to other broad community support services. 6 Improving school readiness, moderating poverty-related social risk determinants, reducing environmental safety hazards, and promoting population-based health remain core goals of contemporary home visiting.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, home visiting gained renewed attention as a strategy for the prevention of child abuse and neglect, promotion of child development, and improvement of parental effectiveness. C. Henry Kempe, MD, called for a home visitor for every pregnant mother and preschool-aged child in his 1978 Abraham Jacobi Memorial Award address. 7 He suggested that integral to every child’s right to comprehensive care is the assignment of a home health visitor to work with the family until each child began school. The visionary pediatrician who developed the concept of the medical home, Cal Sia, MD, reiterated Kempe’s call to action in his 1992 Jacobi Award address 8 based on his experience with Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program, which is an innovative, statewide home-visiting initiative to prevent child abuse and neglect. Another pioneer in modern home visiting, David Olds, PhD, initiated the Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) with families at risk in Elmira, New York, in 1978. 1

Before 2009, at least 22 states recognized the critical role of home visitors within statewide systems for at-risk pregnant mothers, infants, and toddlers from birth to 5 years old. States legislated funding for home-visiting programs while insisting on proof of effectiveness, fiscal accountability, and continuous quality improvement. Even during the Great Recession that followed the US financial crisis of 2007 to 2008, some state governments enacted home-visiting legislation to ensure long-term sustainability through innovative financing mechanisms and the strategic allocation of limited public resources.

In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Public Law Number 111-5) included $2.1 billion for the expansion of Head Start and Early Head Start (including the home-visiting components of Early Head Start) to benefit young children in low-resource communities. The next year, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) (Public Law Number 111-148) designated $1.5 billion, allocated over 5 years, for the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV). The Health Resources and Services Administration currently administers the MIECHV in collaboration with the Administration for Children and Families. The allocations to states, territories, and tribal entities are designed to support the implementation and evaluation of evidence-based home-visiting programs regarding specified goals and objectives. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 5 US territories have home-visiting programs. 9 In addition, ACA funding provides support for home-visiting initiatives to serve American Indian and Alaskan native children through the Tribal MIECHV program. 10

Nineteen home-visiting models have met the criteria of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for evidence of effectiveness through the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) review. Supported by federal grants through the MIECHV, states receive funding to implement 1 or more evidence-based models designated eligible by the MIECHV that best meet the needs of particular at-risk communities. The program objectives must improve outcomes that are statutorily defined and must include increased family economic self-sufficiency, improved health indicators (eg, a reduction in health disparities) in target populations, and improved school readiness. After 2013, potential program outcomes were expanded to include reductions in family violence, juvenile delinquency, and child maltreatment. 11 A review of 4 common programs illustrates the range of measurable outcomes. Healthy Families America identifies family self-sufficiency as a principal objective measured by a reduction of dependence on public assistance. 12 Early Head Start and other home-visiting programs focus on the promotion of child development and positive family relationships. NFP is designed to improve prenatal health, maternal life course development, and positive parenting. 13 Parents as Teachers promotes child development and school readiness. 14

Home visiting for families with young children is an early intervention strategy in many industrialized nations outside of the United States. In several European countries, home health visiting is provided at no cost to the family, participation is voluntary, and the service is embedded in a comprehensive maternal and child health system. 3 While visiting young mothers at home, public health nurses in other countries provide many child health-promotion services that are provided by pediatricians in the United States. For instance, Denmark established home visiting in 1937 after a pilot program showed lower infant mortality rates linked with the services of home visitors. France provides universal prenatal care and home visits by midwives and nurses, who educate families about smoking, nutrition, drug use, housing, and other health-related issues.

The Early Start program in New Zealand targets families with 2 or more risk factors on an 11-point screening measure that includes parent and family functioning. Randomized controlled trials showed improvement in access to health care, lower hospitalization rates for injuries and poisonings, longer enrollment in early childhood education, and more positive and nonpunitive parenting. 15 , 16 The Dutch NFP program, VoorZorg, was found to reduce victimization and perpetration of self-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy and 2 years after birth among low-educated, pregnant young women, 17 and there were fewer reports of child abuse. At 24 months, measurable improvements were evident in the home environments of participating families, and the children exhibited a significant reduction in internalizing symptoms. 18

Paraprofessionals (ie, trained but unlicensed lay people) are often employed as home visitors in low-resource areas of the world. In Haiti, for example, community health workers trained by Partners in Health improve the care of those with HIV, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and such waterborne illnesses as cholera. In southern Mexico and other areas in Central America, “promotoras de salud,” or community health workers, coordinate with lay midwives to care for expectant mothers in rural, isolated, and other low-resource regions. Promotoras are deployed in many regions in the United States and have been recognized by HHS for their ability to reduce barriers and improve access to culturally informed and linguistically appropriate health care. 19

More than 1 in 5 young children in the United States live in families with incomes below the federal poverty level, and more than 2 in 5 live at less than twice that level. 20 Living at or below 200% of the federal poverty level places children, 21 especially infants and toddlers, at high risk for adverse early childhood experiences that lead to lifelong detrimental effects on health, education, and vocational success. 22 Home visitors can help families attain economic self-sufficiency by linking them to community support services (such as quality preschool) while encouraging parents to enroll in training opportunities that lead to employment. Although they differ in structure, targeted populations, and intended outcomes, high-quality home-visiting programs deliver family support and child development services that provide a foundation for physical health, academic success, and economic stability in vulnerable families that are at risk for the adverse effects of poverty and other negative social determinants of health.

By applying multigenerational interventions, home visiting may improve child health and family wellbeing in many domains. Individual neuroendocrine-immune function, behavioral allostasis, and relational health are all established in the first 3 years of life, 23 when home visiting is most often applied. 24 The emerging science of toxic stress indicates that poverty and its accompanying problems, such as food insecurity, may disrupt the architecture and function of the developing brain. 25 , 26 Home visitors have the opportunity to assess risk and protective factors in families, identify potential adversity, and intervene at the earliest opportunity. By promoting supportive relationships, reducing parental stress, and increasing the likelihood of positive experiences, home visiting may help avoid the deleterious behavioral and medical health outcomes associated with child poverty. 27 , – 31

Young mothers in poverty disproportionately suffer moderate to severe symptoms of maternal depression, elevating the risk of poor developmental and educational outcomes for their children. 32 Almost 1 in 4 mothers who are near or below the federal poverty level experience significant depression, but few obtain appropriate treatment. In-home cognitive behavioral therapy is a novel treatment modality for maternal depression that has proved to be effective in early trials. 33 Combining in-home cognitive behavioral therapy with other home-visiting programs, such as Early Head Start, that promote positive parenting and infant development provides a model of 2-generational care that has the potential to mitigate the effects of poverty and improve both family financial stability and school readiness. 34

Home-visiting programs are most effective when they are components of a community-level, comprehensive early childhood system that reaches families as early as possible with needed services, accommodates children with special needs, respects the cultures of the families in the communities, and ensures continuity of care in a continuum from prenatal life to school entry. 35 , 36 An early childhood system may include safety-net resources (such as supplemental food and subsidies for housing, heating, and child care), adult education, job training, cash assistance, quality child care, early childhood education, and preventive health services. 37 Communicating the strengths and risk factors of individual families to the FCMH may further increase the coordination of care and efficient use of services. 38

When the MIECHV program was established by the ACA, HHS established the HomVEE review of the research literature on home visiting. 11 Results of that review are used to identify home-visiting service delivery models that meet HHS criteria for evidence of effectiveness because, by statute, at least 75% of the funds available from the ACA are to be used for programs that use service delivery models that are evidence based. The HomVEE conducts a yearly literature search to identify promising studies of home-visiting models. It includes only studies that are considered to meet quality standards on the basis of overall design (only randomized controlled trials or quasiexperimental studies are included) and design-specific criteria. Studies that meet criteria for entry are then assessed for outcomes in the following 8 domains, as defined by HHS:

Child health;

Maternal health;

Child development and school readiness;

Reductions in child maltreatment;

Reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime;

Positive parenting practices;

Family economic self-sufficiency; and

Linkages and referrals.

To meet HHS criteria for evidence of effectiveness, home-visiting models must demonstrate favorable outcomes in either 1 study with results in 2 or more domains or 2 studies with significant benefits in the same domain. To be included, study designs must meet evaluation quality standards, and outcomes need to show statistically significant benefits using nonoverlapping analytic samples. As of April 2017, the 18 models that meet these standards (along with 2 programs that do not meet criteria for implementation) with target populations, ages of participants, and outcomes for which there is evidence are listed in Table 1 . 11

Home-Visiting Programs Meeting HHS Criteria for Evidence of Effectiveness (as of April 2017)

Reference: https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/home-visiting-evidence-of-effectiveness-review-executive-summary-april-2017 . Descriptions of specific home-visiting programs by state can be accessed at: https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/models.aspx .

Outcomes: (1) child health; (2) maternal health; (3) child development and school readiness; (4) reductions in child maltreatment; (5) reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime; (6) positive parenting practices; (7) family economic self-sufficiency; and (8) linkages and referrals.

A rapidly expanding evidence base documents the benefits of high-quality home-visiting programs, especially when they are integrated in a comprehensive early childhood system of care. 39 Home visiting has been shown to increase children’s readiness for school, promote child health (such as vaccine rates), and enhance parents’ abilities to promote their children’s overall development. There is evidence that home visiting reduces the risk of both child abuse and unintended injury. 16 , 40 Maternal health is improved by more frequent prenatal care, better birth outcomes, and early detection and treatment of depression. 41 Outcome studies have established the effectiveness of home visiting by nurses or community health workers in reducing child maltreatment, 42 improving birth outcomes, 43 and increasing school readiness. 44

A close examination of the evidence of effectiveness published in 2015 by the HomVEE review provides additional insights about the potential benefits and limitations of current models of home visiting. 11 Of the 44 models assessed in 2015, 19 showed improvements in at least 1 primary outcome measure, and 15 had favorable effects on secondary measures. These results are consistent with both the broad scope of many of the models as well as the likelihood that improvements in 1 domain sometimes lead to benefits in another (eg, positive parenting improving child development). All 19 models that showed positive results had evidence of sustained benefits for at least 1 year after enrollment.