Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who explored Central America, overthrew Montezuma and his vast Aztec empire and won Mexico for the crown of Spain.

(1485-1547)

Who Was Hernán Cortés?

He first set sail to the New World at the age of 19. Cortés later joined an expedition to Cuba. In 1518, he set off to explore Mexico.

Cortés strategically aligned some Indigenous peoples against others and eventually overthrew the vast and powerful Aztec empire. As a reward, King Charles I appointed him governor of New Spain in 1522.

Cortés, marqués del Valle de Oaxaca, was born around 1485 in Medellín, Spain. He came from a lesser noble family in Spain. Some reports indicate that he studied at the University of Salamanca for a time.

In 1504, Cortés left Spain to seek his fortune in New World. He traveled to the island of Santo Domingo, or Hispaniola. Settling in the new town of Azúa, Cortés served as a notary for several years.

He joined an expedition of Cuba led by Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar in 1511. There, Cortés worked in the civil government and served as the mayor of Santiago for a time.

Aztec Empire

In 1518, Cortés was to command his own expedition to Mexico, but Velázquez canceled it. In a mutinous act of defiance, Cortés ignored the order, setting sail for Mexico with more than 500 men and 11 ships that year.

In February 1519, the expedition reached the Mexican coast. By some accounts, Cortés then had all his ships destroyed except one, which he sent back to Spain. This brazen decision eliminated the possibility of any retreat.

Cortés became allies with some of the Indigenous peoples he encountered, but with others, he used deadly force to conquer Mexico. He fought Tlaxacan and Cholula warriors and then set his sights on taking over the Aztec empire.

He marched to Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital and home to ruler Montezuma II . After being invited into the royal palace, Cortés took Montezuma hostage and his soldiers plundered the city.

But shortly thereafter, Cortés hurriedly left the city after learning that Spanish troops were coming to arrest him for disobeying orders from Velázquez.

After fending off the Spanish forces, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlán to find a rebellion in progress, during which Montezuma was killed. The Aztecs eventually drove the Spanish from the city, but Cortés returned again to defeat them and take the city in 1521, effectively ending the Aztec empire.

In their bloody battles for domination over the Aztecs, Cortés and his men are estimated to have killed as many as 100,000 Indigenous peoples. King Charles I of Spain (also known as Holy Roman Emperor Charles V) appointed him the governor of New Spain in 1522.

Later Years and Death

Despite his decisive victory over the Aztecs, Cortés faced numerous challenges to his authority and position, both from Spain and his rivals in the New World. He traveled to Honduras in 1524 to stop a rebellion against him in the area.

In 1536, Cortés led an expedition to the northwestern part of Mexico, in the process exploring Baja California and Mexico's Pacific coast. This was to be his last major expedition.

Back in the capital city, Cortés found himself unceremoniously removed from power. He traveled to Spain to plead his case to the king, but he was not reappointed to his governorship.

In 1541, Cortés retired to Spain. He spent much of his later years desperately seeking recognition for his achievements and support from the Spanish royal court. Wealthy but embittered from his lack of support and acclaim, Cortés died in Spain in 1547.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hernán Cortés

- Birth Year: 1485

- Birth City: Medellín

- Birth Country: Spain

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador who explored Central America, overthrew Montezuma and his vast Aztec empire and won Mexico for the crown of Spain.

- Politics and Government

- War and Militaries

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1547

- Death date: December 2, 1547

- Death City: Castilleja de la Cuesta

- Death Country: Spain

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- I love to travel, but hate to arrive.

- He travels safest in the dark night who travels lightest.

- Better to die with honor than live dishonored.

European Explorers

Christopher Columbus

10 Famous Explorers Who Connected the World

Sir Walter Raleigh

Ferdinand Magellan

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Leif Eriksson

Vasco da Gama

Bartolomeu Dias

Giovanni da Verrazzano

Jacques Marquette

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

The Ages of Exploration

Hernán cortés, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

Hernán Cortés was the Spanish conquistador responsible for conquering the Aztec Empire and building Mexico City which secured Spain’s position in the New World.

Name : Hernán Cortés [er-nahn] [kawr-tez]

Birth/Death : 1485 CE - 1547 CE

Nationality : Spanish

Birthplace : Seville, Spain

Hernan Cortes

Print of Hernan Cortes, Spanish conquistador who conquered the Aztec Empire, and established a new Spanish territory called "New Spain," present day Mexico. The Mariners Museum F1230.C8 S4

Introduction With superior firepower, 600 Spaniards, a dozen horses, and thousands of native allies, Hernán Cortés conquered Mexico for Spain. This also marked the fall of the Aztec Empire. His conquest enabled Spain to create a stronghold and colonies in the New World. From a young age, Cortés sought wealth and adventure. History remembers him as a fierce conquistador (Spanish for “conqueror”). Despite his reputation, he opened the door for further exploration and conquest to the south and north

Biography Early Life Hernán (or Hernándo) Cortés was born in 1485 in the village of Medellín, located in the Estremadura province of Spain. His parents were Martin Cortés de Monroy and Catalina Pizarro Altamirano. Cortés was a distant cousin to Francisco Pizarro, the explorer who conquered the Incan empire in Peru. Cortés’ family was noble but not extremely wealthy. As a young child, Cortés was frequently ill, but his health improved when he was a teenager. In 1499, at the age of 14, he was sent to the University of Salamanca to prepare for a law career. However, Cortés eventually grew tired of his studies and after two years dropped out of school and returned home. Cortés wanted a life of action, and was fascinated by the tales of gold and riches in the New World. He signed up with an expedition to the New World led by Nicolás de Ovando, who was the governor of Hispaniola. But an accident from a fall which buried him under rubble severely injured his back. 1 So he could not sail with Ovando’s fleet.

Talk of the New World and the allure of wealth continued to captivate young Cortés. In 1504, he sought passage on a ship to Santo Domingo, Hispaniola (modern day Dominican Republic). Cortés began farming in the Spanish colony, which brought him much wealth, and owned several native slaves. He finally got his first taste of exploration when he joined a mission under led by Diégo Velasquez in 1511. When he returned, he promised to marry Catalina Suarez, the sister of his friend Juan Suarez, but backed out at the last minute. Velasquez, now governor of Cuba, imprisoned Cortés for not upholding his promise. 2 Eventually, Cortés agreed to marry Catalina, but relations between Velázquez and Cortés remained tense.In 1518, appointed Cortés to lead an expedition to conquer the interior of Mexico. He then withdrew the order because he grew suspicious of Cortés’ strong will and thirst for power. Cortés disobeyed Velasquez and set out for Mexico in 1519 to begin his invasion.

Voyages Principal Voyage In 1519, Hernán Cortés left Cuba with about 600 men, and set out for the Yucatan region of Mexico. 3 He first arrived in Cozumel, and began to explore the land for colonization. He encountered natives, and their large pyramid. He noticed the blood stains and human remains, and learned that this pyramid was used for human sacrifices to their gods. 4 Appalled, Cortés began his efforts to convert the natives to Christianity. He tore down their idols and replaced them with crosses and statues of the Virgin Mary. Cortés relied on native translators and guides to communicate with the natives, and travel the land. Soon after, Cortés and his men sailed on and landed at Tabasco. Here, Cortés and his men clashed with the natives. On March 25, 1519, in the Cintla Valley, the two sides fought in a battle known as the Battle of Cintla. The natives were no match for the Spanish soldiers weaponry and armor. 800 Tabascans were killed; only 2 Spanish men were killed. 5 The Tabascans pledged their loyalty to Spain, and gave Cortés gold and slave women.

One of the chieftains gifted a slave woman to Cortés named Malinche. She was bilingual so she spoke both Aztec and Mayan languages, which made her very useful to Cortés. She eventually learned Spanish, and became Cortés’s personal interpreter, guide, and mistress. They had a son named Martin. Having conquered the Tabascan people, Cortés moved up the coast to Tlaxcala, a city of the mighty Aztec empire. The Aztecs were not always popular rulers among their subjected cities. When Cortés learned of this, he used it to his advantage. He met with Aztec ambassadors, and told them he wished to meet the great Aztec ruler Montezuma. Xicotenga, a ruler in the city Tlaxcala, saw an ally in Cortés, and an opportunity to overthrow the capital city of Tenochtitlán. They formed an allegiance, and Cortés was given several thousand warriors to add to his ranks. By this time, Cortés’ men were beginning to grumble about Cortés. He continued ignoring Velázquez’s orders to return to Cuba, and the men felt he was overstepping his authority. Afraid his men would leave, Cortés destroyed all the ships. 6 With nowhere for the men to go, they followed Cortés onward to Tenochtitlán.

Subsequent Voyages Cortés and his men marched to Tenochtitlán. They reached the capital of the Aztec empire on November 8, 1519. 7 The ruler of the Aztec civilization was Montezuma II. Montezuma, though uncertain of the Spaniards’ intent, welcomed them graciously. He gave them a tour of his palace, and they were given extravagant gifts. This fueled the Spaniards’ greed and relations turned hostile shortly after. Cortés took Montezuma captive and the Spaniards raided the city. Montezuma was murdered shortly after from being stoned by his own people. 8 In 1520, Spanish troops had been sent to Mexico to arrest Cortés for disobeying orders. He left Tenochtitlán to face the opposing Spaniards. After defeating them, Cortés returned to the Aztec capital to find a rebellion in progress. The Spaniards had been driven from the city. Cortés reorganized his men and allies, and seized control of neighboring territories around the capital. They regained control of the city by August of 1521. This marked the fall of the Aztec empire. Cortés had seized control of Mexico for Spain. Cortés was named governor, and went on to establish Mexico City, built on the ruins of the fallen Aztec capital.

Later Years and Death Several years after his conquest of Mexico, Cortés endured many challenges to his status and position. He had been appointed the governor, yet was removed from power after returning from a trip to Honduras in 1524. Cortés went to Spain to met with the Spanish king in order to reclaim his title, but never gained it back. He returned to Mexico after his failing with the king and partook in several more expeditions throughout the New World. Cortés retired in Spain in 1540. He died seven years later on December 2, 1547 at his home in Seville from a lung disease called pleurisy. 9

Legacy Hernán Cortés remains one of the most successful of the Spanish conquistadors. He was a hero in the 16th century, but history remembers him differently. He had many conquests during his life. But he is perhaps most known for his conquer of the Aztec Empire in 1521. He enslaved much of the native population, and many of the indigenous people were wiped out from European diseases such as smallpox. He was a smart, ambitious man who wanted to appropriate new land for the Spanish crown, convert native inhabitants to Catholicism, and plunder the lands for gold and riches. However, we still recognize his role in history. He helped oversee the building of Mexico City, which is still Mexico’s capital today. He opened the door for further exploration and conquest of Central America to the south, and eventually led to the acquisition of California towards the north.

- Patricia Calvert, Hernándo Cortés: Fortune Favored the Bold (New York: Benchmark Books, 2003), 11.

- Buddy Levy, Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 8.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 63.

- Levy, Conquistador, 12.

- Levy, Conquistador , 26-27.

- Thomas Streissguth, Hernán Cortés , (Mankato: Capstone Press, 2004), 12.

- Jeff Donaldson-Forbes, Hernán Cortés (New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2002), 21

- Donaldson-Forbes, Hernán Cortés , 22

- L. L. Owens, A Journey with Hernán Cortés (Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., 2017), 32.

Bibliography

Calvert, Patricia. Hernándo Cortés: Fortune Favored the Bold . New York: Benchmark Books, 2003.

Donaldson-Forbes, Jeff. Hernán Cortés . New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, 2002.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration . New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Levy, Buddy. Conquistador: Hernán Cortés, King Montezuma, and the Last Stand of the Aztecs . New York: Bantam Books, 2008.

Owens, L.L. A Journey with Hernán Cortés . Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., 2017.

Streissguth, Thomas. Hernán Cortés . Mankato: Capstone Press, 2004.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Hernán Cortés Conquered the Aztec Empire

By: Karen Juanita Carrillo

Updated: June 26, 2023 | Original: May 20, 2021

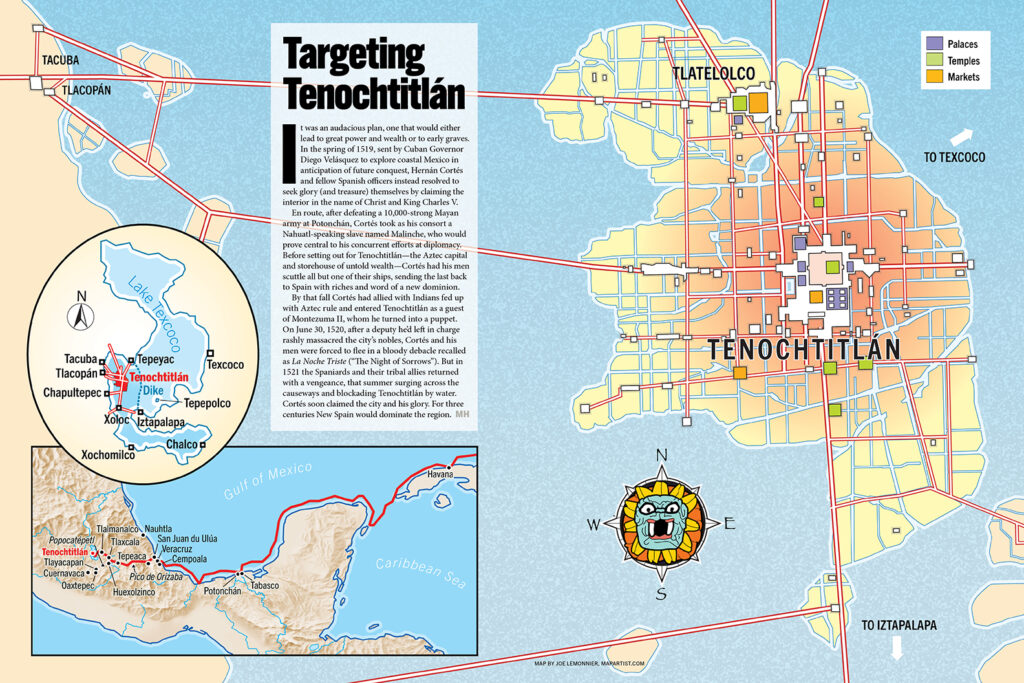

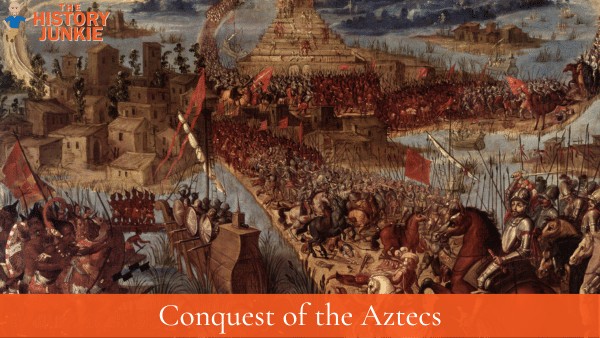

The Aztec Empire , Mesoamerica’s dominant power in the 15th and early 16th centuries controlled a capital city that was one of the largest in the world. Itzcoatl, named leader of the Aztec/Mexica people in 1427, negotiated what has become known as the Triple Alliance —a powerful political union of the city-states of Mexico-Tenochtitlán, Tetzcoco and Tlacopán. As that alliance strengthened between 1428 and 1430 it reinforced the leadership of the Aztecs, making them the dominant Nahua group in a landmass that covered central Mexico and extended as far as modern-day Guatemala.

And yet Tenochtitlán fell into decline after the siege and destruction of the city by the Spanish in 1521—less than two years after Hernándo Cortés and Spanish conquistadors first set foot in the Aztec capital on November 8, 1519. How did Cortés manage to overthrow the seat of the Aztec Empire?

Tenochtitlán: A Dominant Imperial City

When Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Aztec imperial city in 1519, Mexico-Tenochtitlán was led by Moctezuma II. The city had prospered and was estimated to host a population of between 200,000 and 300,000 residents.

At first , the conquistadors described Tenochtitlán as the greatest city they had ever seen. It was situated on a human-made island in the middle of Lake Texcoco. From its central location, Tenochtitlán served as a hub for Aztec trade and politics. It featured gardens, palaces, temples and raised roads with bridges that connected the city to the mainland.

Other city-states were forced to pay periodic tributes to Tenochtitlán’s public markets and to its religious center, the Templo Mayor or “Great Temple.” Religious tributes sometimes took the form of human sacrifices . While the Aztec’s monetary and religious demands empowered the empire, it also fostered resentment among surrounding city-states.

Hernándo Cortés Makes Allies with Local Tribes

Hernándo Cortés formed part of Spain’s initial colonization efforts in the Americas. While stationed in Cuba, he convinced Cuban Governor Diego Velázquez to allow him to lead an expedition to Mexico, but Velázquez then canceled his mission. Eager to appropriate new land for the Spanish crown, convert Indigenous people to Christianity and plunder the region for gold and riches, Cortés organized his own rogue crew of 100 sailors, 11 ships, 508 soldiers and 16 horses. He set sail from Cuba on the morning of February 18, 1519, to begin an unauthorized expedition to Mesoamerica.

Arriving on the Yucatán coast, Cortés encountered Indigenous people who told him about other Europeans who had been shipwrecked and captured by local Mayans. Cortes freed Jerónimo de Aguilar , a Franciscan friar, from the Mayans and made Aguilar part of his crew. Aguilar turned out to be an invaluable asset to Cortes due to his ability to speak Chontal, the local Mayan language. With Aguilar at his side, Cortés and his conquistadors continued traveling the region, battling Indigenous groups along the way.

Cortés and his men then acquired another asset when an Aztec chief gifted them some 20 enslaved young Mayan women, including Malinalli, a Nahua woman from the Mexican Gulf Coast. Malinalli became baptized with the Christian name Marina and was later known as La Malinche. La Malinche spoke both the Aztec language of Náhuatl and Mayan Chontal and worked alongside the Spanish invaders, providing the conquistadors with the ability to communicate with any Indigenous groups they encountered.

With La Malinche and Aguilar in tow, the conquistadors made their way to the island city of Tenochtitlán where they were initially welcomed by Emperor Moctezuma II. When Cortés became concerned that Moctezuma's people would turn against his men, he placed Moctezuma under house arrest and Cortés attempted to rule through the detained Moctezuma.

Soon Cortés received word that the Cuban governor had sent a Spanish force to arrest Cortés for insubordination. Leaving his top lieutenant Pedro de Alvarado in charge of Tenochtitlán, Cortés took men to attack the Spanish forces at the coast. Cortes's men defeated the troops and took the surviving Spanish soldiers back with him as reinforcements to Tenochtitlán. In Cortés' absence, Alvarado had hundreds of Aztec nobles killed during a ceremonial feast, leading to further unrest among the Aztec people.

Tenochtitlán residents demanded the Spanish be removed from the city. When the detained Moctezuma could no longer control Tenochtitlán’s residents, the Spaniards either allowed him to die during a skirmish in 1520 or killed him—depending on varying accounts .

Driven from the capital, the Spanish later circled back with a small fleet of ships. Working in alliance with some 200,000 Indigenous warriors from city-states, particularly the Tlaxcala and Cempoala (groups who had resented the Aztec/Mexicas and wanted to see them vanquished), the Spanish conquistadors held Tenochtitlán under siege from May 22 through August 13, 1521—a total of 93 days.

Disease Further Weakens the Aztec

With Tenochtitlán encircled, the conquistadors relied on their Indigenous allies for key logistical support and launched attacks from local Indigenous encampments. Meanwhile, another factor began to take its toll. Unbeknownst to the Spanish, some among their ranks had been infected with smallpox when they had departed Europe. Once these men arrived in the Americas, the virus began to spread—both among their indigenous allies and the Aztecs. (Some research has suggested that salmonella , not smallpox, had weakened the Aztecs.)

The first known case reportedly emerged in Cempoala—one of the city-states that had allied with the Spanish—when an enslaved African came down with the disease. The virus then spread. As the Spaniards and their allies later attacked Tenochtitlán, even when they lost battles, the smallpox virus infected the Aztecs. Aztec troops, members of the noble class, farmers and artisans all fell victim to the disease.

While many Spaniards had acquired immunity to the disease, the virus was new in the Americas and few Indigenous understood it. The bodies of smallpox victims piled up in the streets of Tenochtitlán and, with the city under siege, there were few available ways to dispose of the bodies.

Spaniards and their allies were taken in as prisoners (the Aztecs tended to hold captured prisoners for sacrifice to the gods, rather than kill them in battle) and traces of the virus were left on the clothes, hair and on dead bodies of those who had had the disease. As Tenochtitlán residents contracted smallpox they had no place to turn for help. Aztec priests and medicinal practitioners knew of no remedy and Tenochtitlán residents had little immunity.

The Spanish Wielded Better Weaponry

The conquistadors arrived in Mesoamerica with steel swords, muskets, cannons, pikes, crossbows, dogs and horses. None of these assets had yet been used in battle in the Americas. The Aztecs fought the Spanish with wooden broadswords, clubs and spears tipped with obsidian blades. But their weapons proved ineffective against the conquistadors’ metal armor and shields.

When the Spanish arrived in the Americas they came from a war-oriented culture that had seen battle against other European nations for dominance and against North Africans for sovereignty. The conquistadors arrived in Mesoamerica with better guns and had been trained in tactical strategies. They deployed a cavalry that could chase down retreating warriors, dogs trained to track down and encircle enemies and horses capable of trampling adversaries.

Up against large armies of Spanish and Indigenous forces, surrounded and cut off from the mainland, and with a population succumbing to an unknown, devastating virus, the Aztec Empire was unable to fight off the invading Spanish conquistadors. The Aztecs, including members of the Aztec royal family—then were forced to adjust to life under Spanish rule.

"Cada Uno En Su Bolsa Llevar Lo Que Cien Indios No Llevarían: Mexica Resistance and the Shape of Currency in New Spain, 1542-1552.” by Allison Caplan, American Journal of Numismatics (1989-), vol. 25, 2013, pp. 333–356. JSTOR .

“Jeronimo de Aguilar,” American Historical Association .

“Aztec Warfare Imperial Expansion and Political Control,” by Ross Hassig, University of Oklahoma Pres s, 1988, p. 244.

“Searching for the Secrets of Nature The Life and Works of Dr. Francisco Hernández,” by Dora B. Weiner, Stanford University Press , 2000, p. 86.

“Viruses, Plagues, and History Past, Present, and Future,” by Michael B. Oldstone, Oxford University Press , 2020, p. 46.

“So Why Were the Aztecs Conquered, and What Were the Wider Implications? Testing Military Superiority as a Cause of Europe's Pre-Industrial Colonial Conquests,” by George Raudzens. War in History, vol. 2, no. 1, 1995, pp. 87–104. JSTOR . Accessed May 18, 2021.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Premium Content

- HISTORY MAGAZINE

Guns, germs, and horses brought Cortés victory over the mighty Aztec empire

The Aztec outnumbered the Spanish, but that didn't stop Hernán Cortés from seizing Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, in 1521.

After the expedition led by Vasco Núñez de Balboa who crossed Central America to reach the Pacific in 1513, Europeans began to see the full economic potential of this "New World." At first, colonization by the burgeoning new world power, Spain, was centered on the islands of the Caribbean, with little contact with the complex, indigenous civilizations on the mainland.

It was not long, however, before the lure of wealth spurred Spain’s adventurers beyond exploration and into a phase of conquest that would lay the foundations of the modern world. Whole swaths of the Americas rapidly fell to the Spanish crown, a transformation begun by the ruthless conqueror of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés. (See also: New clues to the lost fleet of Cortés .)

Cortés beginnings

Like other conquistadores of the early 16th century, Cortés had already gained considerable experience by living in the New World before embarking on his exploits. Born to modest lower nobility in the Spanish city of Medellín in 1485, Cortés stood out at an early age for his intelligence and his restless spirit of adventure inspired by the recent voyages of Christopher Columbus.

In 1504, Cortés left Spain for the island of Hispaniola (today, home to the Dominican Republic and Haiti), where he rose through the ranks of the fledgling colonial administration. In 1511 he joined an expedition to conquer Cuba and was appointed secretary to the island's first colonial governor, Diego Velázquez.

During these years, Cortés developed the skills that would stand him in good stead in his short, turbulent career as a conquistador. He gained valuable insights into the organization of the islands’ indigenous peoples and proved an adept arbiter in the continual squabbles that broke out among the Spaniards, forever vying to enlarge their estates or snag lucrative administrative positions.

In 1518 Velázquez appointed his secretary to lead an expedition to Mexico. Cortés—as Velázquez was to discover to his cost—was set on becoming a leader rather than a loyal follower. He set off for the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in February 1519 with 11 ships, about 100 sailors, 500 soldiers, and 16 horses. Over the following months Cortés would take matters into his own hands, disobey the governor’s orders, and turn what had been intended to be an exploratory mission into a historic military conquest.

Aztec introductions

To the Aztec, 1519 was a year that began with their empire as the uncontested power in the region. Its capital city, Tenochtitlan, ruled 400 to 500 small states with a total population of five to six million. The fortunes of the kingdom of Moctezuma, however, were doomed to a swift and spectacular decline once Cortés and his men disembarked on the Mexican coast. (See also: Rare Aztec Map Reveals a Glimpse of Life in 1500s Mexico. )

Having rapidly imposed control over the indigenous population in the coastal region, Cortés was given 20 slaves by a local chieftain. One of them, a young woman, could speak several local languages and soon learned Spanish too. Her linguistic skills would prove crucial to Cortés’s invasion plans, and she became his interpreter as well as his concubine. She soon came to be known as Malinche, or Doña Marina. The conquistador had a son with her, Martín, who is often regarded as the first ever mestizo—a person of mixed European and American Indian ancestry. (See also: Call the Aztec midwife: Childbirth in the 16th century. )

The news of the foreigners’ arrival soon reached the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma, in Tenochtitlan. To appease the Spaniards, he sent envoys and gifts to Cortés, but he only succeeded in inflaming Cortés’s desires for more Aztec riches. Cortés once described the land near Veracruz, the city he founded on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, as rich as the mythical land where King Solomon obtained his gold. As a mark of his ruthlessness, and to quash any misgivings his crew may have had in disobeying the orders of Governor Velázquez, Cortés ordered the destruction of the fleet he had sailed with from Cuba. There was now no turning back.

Mosaic mask of turquoise and lignite covers a human skull and represents an Aztec god, Tezcatlipoca.

Cortés had a talent for observing and manipulating local political rivalries. On the way to Tenochtitlan, the Spaniards gained the support of the Totonac peoples from the city of Cempoala, who hoped to be freed from the Aztec yoke. Following a military victory over another native people, the Tlaxcaltec, Cortés incorporated more warriors into his army. Knowledge of the divisions among different native peoples, and an unerring ability to exploit them, was central to Cortés’s strategy.

The Aztec had allies too, however, and Cortés was especially belligerent toward them. The holy city of Cholula, which joined with Moctezuma in an attempt to stall the Spaniards, was sacked for two days at Cortés’s command. After a grueling battle lasting more than five hours, as many as 6,000 of its people were killed. Cortés’s forces seemed invincible. In the face of their unstoppable advance, Moctezuma stalled for time, allowing the Spaniards and their allies to enter Tenochtitlan unopposed in November 1519.

Fighting on two fronts

Fear gripped the huge Aztec capital on Cortés’s entry, the chroniclers wrote: Its 250,000 inhabitants put up no resistance to Cortés’s small force of a few hundred men and 1,000 Tlaxcaltec allies. At first Moctezuma formally received Cortés. Seeing the value of the emperor as a captive, Cortés seized him and guaranteed his power over the city.

Establishing a pattern that would recur throughout his career, Cortés soon found himself as much at threat from his own compatriots as from the peoples he was trying to subdue. At the beginning of 1520 he was forced to leave Tenochtitlan to deal with a punitive expedition sent from Cuba by the enraged Diego Velázquez. In his absence, Cortés left Tenochtitlan under the command of Pedro de Alvarado and a garrison of 80 Spaniards.

You May Also Like

These 5 leaders' achievements were legendary. But did they even happen?

‘A ball of blinding light’: Atomic bomb survivors share their stories

The incredible details 'Masters of the Air' gets right about WWII

The hotheaded Alvarado lacked Cortes’s skill and diplomacy. During Cortes’s absence, Alvarado’s execution of many Aztec chiefs enraged the people. After defeating Velázquez’s forces, Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan on June 24, 1520, to find the city in revolt against his proxy. For several days, the Spaniards vainly used Moctezuma in an attempt to calm tempers, but his people pelted the puppet king with stones. Moctezuma died a few days later, but his successors would fare no better than he did.

On June 30, 1520, the Spanish fled the city under fire, suffering hundreds of casualties. Some Spaniards died by drowning in the surrounding marshes, weighed down by the vast amounts of treasure they were trying to carry off. The event would come to be known as the Night of Sorrows.

Technology Triumphs

Although the Aztec had the superior numbers, advanced Spanish weaponry ultimately gave them the upper hand. With firearms and steel blades at his disposal, just one Spaniard might annihilate dozens or even hundreds of opponents: “On a sudden, they speared and thrust people into shreds,” wrote one indigenous chronicler, having witnessed the terrifying impact of European arms. “Others were beheaded in one swipe... Others tried to run in vain from the butchery, their innards falling from them and entangling their very feet.”

A smallpox epidemic prevented the Aztec forces from finishing off Cortés’s defeated and demoralized army. The outbreak weakened the Aztec while giving Cortés time to regroup. Spain would win the Battle of Otumba a few days later. Skillful deployment of cavalry against the elite Aztec jaguar and eagle warriors carried the day for the Europeans and their allies.“Our only security, apart from God,”Cortés wrote,“is our horses.”

Victory allowed the Spaniards to rejoin with their Tlaxcaltec allies and launch the recapture of Tenochtitlan. Waves of attacks were launched on settlements near the Aztec capital. Any resistance was brutally crushed: Many indigenous enemies were captured as slaves and some were even branded following their capture. The sacking also allowed the Spaniards to build up their large personal retinues, taking captives to use as servants and slaves, and kidnapping others for exchanges and ransoms. Growing in number to roughly 3,000 people, this group of captives vastly outnumbered the fighting Spaniards.

Fall of the Aztec

For an assault on a city the size of Tenochtitlan, the number of Spanish troops seemed paltry—just under 1,000 soldiers, including harquebusiers, infantry, and cavalry. However, Cortés knew that his superior weaponry, coupled with the additional 50,000 warriors provided by his indigenous allies, would conquer the city, which was already weakened from starvation and thirst. In May 1521 the Spaniards had cut off the city’s water supply by taking control of the Chapultepec aqueduct.

Even so, the siege of Tenochtitlan was not a given. During fighting in July 1521, the Aztec held strong, even capturing Cortés himself. Wounded in one leg, the Spanish leader was ultimately rescued by his captains. During this setback for the conquistador, the Aztec warriors managed to regain lost ground and rebuild the city’s fortifications, pushing the Spanish onto the defensive for nearly three weeks. Cortés ordered the marshland to be filled with rubble for a final assault. Finally, on August 13, 1521, the city fell.

“Not a single stone remained left to burn and destroy,” one witness wrote. The loss of human life was staggering, both in absolute figures and in its disproportionality. During the siege, around 100 Spaniards lost their lives compared to as many as 100,000 Aztec.

Ladies' Man

According to the chronicler Francisco López de Gómara, Cortés was “very given to women and always gave into temptation.” His biography abounds in romantic entanglements. Throughout his career, Cortés's personal life held a selfish, manipulative streak. In 1514 he married a young Spanish woman named Catalina Suárez, a relative of Governor Diego Velázquez, who soon promoted Cortés after the wedding. But Cortés was not faithful. After the conquest of Mexico, he and Malinche, an Aztec woman who served as his interpreter, had a son together. The marriage to Caralina only ended when she was found dead under mysterious circumstances in 1522. Cortés was suspected of her murder, but nevery charged. Cortés then took as a consort Princess Isabel Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor's daughter. She and Cortés had a daughter, but he later abandoned them. In 1529 Cortés took a Spanish noblewoman, Juana de Zúñiga, as his bride and became a marquis, securing both a high social status and a rather rakish reputation.

The conquest of Tenochtitlan and the subsequent consolidation of Spanish domination over the former Aztec Empire was the first major possession in what became the Spanish Empire. This vast territory would reach its greatest extent in the 18th century, with territory throughout North and South America.

Cortés’s triumph would be short-lived. In just a few years, he would lose many of his lands in the New World. Despite being made a marquis years later, the Conqueror of Mexico did not have a glorious end. In 1547, at the age of 62, he died in a village near Sevilla, Spain, embroiled in lawsuits and his health broken by a series of disastrous expeditions. Decades of rapid expansion in the Americas seemed to have eclipsed his own exploits, and few bells tolled for the man whose ruthlessness and cunning transformed the Americas.

Related Topics

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

- CONQUISTADORES

The truth behind the turbulent love story of Napoleon and Joséphine

Who were the Aztec, really? It’s complicated.

What lifting weights does to your body—and your mind

'Magic' mirror in Elizabethan court has mystical Aztec origin

What's worse than a hangover? Hangxiety. Here's why it happens.

- Paid Content

- Environment

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Women of Impact

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Destination Guide

- Adventures Everywhere

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Hernán Cortés: Conqueror of the Aztecs

Hernán Cortés and his conquistadors toppled the Aztec Empire.

In the Caribbean

Arrival in mexico, conquering the aztecs, the siege of tenochtitlán, later years.

Hernán Cortés was a Spanish conquistador, or conqueror, who is best remembered for conquering the Aztec Empire in 1521 and claiming Mexico for Spain. He also helped colonize Cuba and became a governor of New Spain, a vast area that included large parts of North, Central and South America, as well as several Pacific island archipelagos.

"Like many explorers we know about today, Hernán (also known as Hernando) Cortés's role in the Age of Exploration was influential but controversial," said Erika Cosme, formerly the administrative coordinator of education and digital services at The Mariners' Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia. "He was a smart, ambitious man who wanted to appropriate new land for the Spanish crown, convert Native inhabitants to Catholicism and plunder the lands for gold and riches."

Cortés was born in 1485 in Medellín, Spain. He was the only son of noble parents, though his family was not wealthy. He was apparently a clever but difficult child and was the source of much anxiety to his parents, according to Britannica . Cortés' secretary, who wrote a history of Cortés' New World expedition that contained some biographical information, described the conquistador, in general, as ruthless, haughty, mischievous and quarrelsome.

At age 14, Cortés was sent to study law at the University of Salamanca in Spain, but he was unhappy and craved a life of action, so he dropped out after two years. Cortés became fascinated with tales of Christopher Columbus' New World explorations.

Columbus and his expedition members were the first Europeans to see the West Indies when they landed at San Salvador Island in the Bahamas and explored other islands in 1492. Columbus had set sail hoping to find a route to Asia or India. He wanted to profit from and hasten trade for nutmeg, cloves and pomander (a ball of fragrant spices) from the Indonesian "Spice Islands," and pepper and cinnamon from India, which were in high demand, Cosme told Live Science.

However, Columbus' expedition failed to reach its intended destination and instead stumbled upon the Americas, which were completely unknown to Europeans at the time. (Columbus was initially convinced he'd reached Asia, which is why the region is called the "West Indies," according to Britannica.) Reports of Columbus' journey caused a wave of excitement in Spain and Europe, and several more expeditions set out to explore this "New World" in the following years.

Cortés was eager to be part of the dynamic movement. "For individual explorers, gaining public fame could potentially make them rich," Cosme said. According to the Thought Company , a website that covers history and science, many of these explorers were ambitious men who had been professional soldiers or were mercenaries and often acted on their own initiative rather than seeking funding from the Spanish Crown. Consequently, their expeditions were often privately funded. At the same time, they could not simply decide to mount an expedition without official sanction; they had to seek authorization from colonial officials.

Cortés decided to seek fortune and adventure in Hispaniola (modern-day Dominican Republic and Haiti). In 1504, at age 19, Cortés set sail for the New World.

Cortés spent seven years on Hispaniola, living in the town of Azua and working as a notary and farmer. In 1511, he joined Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar's expedition to conquer Cuba, which was occupied by at least two major Native American groups, the Taíno and the Guanahatabey. After the conquest, Cortés served as a clerk to the treasurer and later as mayor of Santiago, a town which had been established after the conquest and served as the island's capital for a brief time until the establishment of Havana in 1515. Cortés' time in Cuba made him wealthy because he was able to buy enslaved people and have them work the land he had acquired. He was able to purchase a house in Santiago and gain considerable influence among the colonists, according to Britannica .

Despite his success, Cortés was hungry for more power. In 1518, he convinced Velázquez, who was by that time the governor of Cuba, to grant him permission to lead an expedition to Mexico , which the Spanish had come into contact with earlier that year. Velázquez appointed Cortés' captain-general of the expedition, according to Britannica , but soon grew increasingly jealous of Cortés' power and influence. Velázquez canceled the voyage at the last minute, but Cortés ignored his orders and set sail with 11 ships and more than 500 men.

In February 1519, Cortés' ships reached the Mexican coast at Yucatán, which was the domain of Mayan-speaking peoples. The Spanish were eager to settle in the region, and Cortés was also interested in converting Native Americans to Christianity. "His view on the Indigenous people was similar to the majority of Europeans of that day — they were inferior culturally, technologically and religiously," Cosme said. In Cozumel, an island off the Yucatán coast that was one of the first places the Spaniards landed, Cortés learned of various rituals, "including human sacrifice of the Natives to their many gods," Cosme said. "He and his men removed and destroyed the pagan idols, and replaced them with crosses and figures of the Virgin Mary."

Cortés' force then continued sailing west to Tabasco, where it encountered resistance from Native warriors. The Spanish force overpowered them, and the Natives surrendered. Not only did the Spaniards' armaments — steel weapons, arquebuses and crossbows — prove superior in the clash, but so did Cortes' horses . He brought 16 horses along on the expedition; the Indigenous people were not familiar with them and were reportedly terrified of the beasts. Bernal Díaz del Castillo , a soldier who marched with Cortés and later wrote a history of the expedition called " The True History of the Conquest of New Spain ," described the Natives' encounter with the horses: "The Indians, who had never seen any horses before, could not think otherwise than that horse and rider were one body. Quite astounded at this to them so novel a sight, they quitted the plain and retreated to a rising ground."

The Natives provided the Europeans with food, supplies and 20 women, including an interpreter called Malintzin (also known as La Malinche or Doña Marina). La Malinche became an important figure in Cortés' life and legacy.

"She became bilingual, speaking Aztec and Mayan languages, which made her very useful to Cortés," Cosme said. "She eventually learned Spanish and became Cortés' personal interpreter, guide and mistress. She actually had a pretty high status for both a woman and a Native during this time and place among the Spaniards."

Díaz described La Malinche as "an excellent woman and fine interpreter throughout the wars in New Spain, Tlaxcala and Mexico … This woman was a valuable instrument to us in the conquest of New Spain. It was, through her only, under the protection of the Almighty, that many things were accomplished by us: without her we never should have understood the Mexican language, and, upon the whole, have been unable to surmount many difficulties."

Cortés and La Malinche had a child together named Martín, who is sometimes called "El Mestizo." He was one of the first children of mixed Indigenous and Spanish heritage. Eventually, in 1522, Cortés' Spanish wife, Catalina Suarez, came to Mexico. After her arrival, historians are unsure if Cortés continued to acknowledge La Malinche or Martín, Cosme said. "It would seem his desire to maintain his reputation and standing among the Spanish community was stronger than his need to be a husband and father to Malinche and Martín." Nonetheless, Catalina died under mysterious circumstances soon after arriving, and eventually Cortés took another Spanish wife when he returned briefly to Spain in 1528, according to Britannica.

After a few months in Yucatán, Cortés sailed west again. On the southeastern coast of what is now Mexico, he founded Veracruz, where he dismissed the authority of Velázquez and declared himself under orders from King Charles I of Spain. He disciplined his men and trained them to act as a cohesive unit of soldiers, and prepared them for the long march to Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital. And in an act that signified his fierce determination, he burned his ships to make retreat impossible, though some scholars have disputed this story.

Díaz related how Cortés exhorted his soldiers on the eve of their long march. "Cortes then adduced many beautiful comparisons from history, and mentioned several heroic deeds of the Romans ,” Díaz wrote "We answered him, one and all, that we would implicitly follow his orders, as the die had been cast, and we, with Caesar , when he had passed the Rubicon, had now no choice left; besides which, everything we did was for the glory of God and his majesty the emperor."

Cortés had heard of the Aztecs (also known as the Mexica) and knew that they, and their leader Montezuma II (also spelled Moctezuma), were a primary force in Mexico. According to Britannica, the Aztec Empire ruled a large swath of what is today modern Mexico and parts of central America during the 15th and 16th centuries. The Aztecs were accomplished warriors, engineers, artisans and agriculturalists known for creating a thriving society that ruled over a surrounding, often hostile amalgam of various Native Americans with different languages and cultures. Although the Aztecs had been one of many small groups in the Valley of Mexico, they had expanded aggressively during the 15th century by conquering their neighbors, according to World History Encyclopedia . At first, the Aztecs had ruled with the help of two other cities in the region, Texcoco and Tlacopan, a confederation known as the Triple Alliance. Eventually, however, the Aztecs came to dominate the Triple Alliance and ruled alone.

"Cortés arrived in the great Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán [on Nov. 8] in 1519," Cosme said. "Although he was kindly received by the Aztec emperor Montezuma, Cortés' intentions were less benevolent." He set out to rule them.

Tenochtitlan was the religious and political center of the Aztec Empire. It was much larger than many European cities of the time and hosted a population of about 400,000 people, according to Britannica . (By comparison, the city of Paris in the 16th century had an estimated population of 225,000, according to the website Statista .) It had been founded in A.D. 1325 on two small islands in the middle of Lake Texcoco and was connected to the mainland by several broad causeways. In the heart of the city was the temple district, which boasted the Great Temple, or Hueteocalli as the Aztecs called it. This imposing structure, which loomed above the surrounding city, was dedicated to two Aztec gods: Huitzilopochtli, the war god, and Tláloc, the rain god. Other prominent buildings included the pyramid of Tezcatlipoca, a creator god, and the temple of Quetzalcoatl, the "feathered serpent" and the god of art and learning who was associated with the planet Venus .

Díaz described the awe Tenochtitlan inspired among the Spaniards upon arriving: "When we gazed upon all this splendor at once, we scarcely knew what to think, and we doubted whether all that we beheld was real. A series of large towns stretched themselves along the banks of the lake, out of which still larger ones rose magnificently above the waters. Innumerable crowds of canoes were plying everywhere around us; at regular distances we continually passed over new bridges, and before us lay the great city of Mexico in all its splendor."

In some accounts, Cortés' arrival coincided with an important Aztec prophecy. The Aztec god Quetzalcoatl was set to return to Earth . In this interpretation, Montezuma was hesitant to confront the Spanish for fear of angering the returned god. However, this interpretation has been disputed by many modern scholars who have argued that it is essentially a myth that was propagated many years after the conquest as a way for Europeans to justify their actions and foster the notion that the Aztecs saw the Spanish as superior.

Montezuma sent out envoys to meet the conquistador as he neared the capital. The Spanish fired shots from their arquebuses and cannons, which stunned the Natives and further intimidated them.

Cortés entered the city, and at first the meeting between the two leaders, though tense, was peaceful. Montezuma gave the conquistador gifts of gold . But things changed quickly. Cortés took Montezuma hostage and sacked the city. La Malinche helped Cortés manipulate Montezuma and rule Tenochtitlán through him. "It is also said that she informed Cortés of an Aztec plot to destroy his army," Cosme said.

The Spanish army had help sacking the city. Though Cortés enslaved much of the Native population, other Indigenous groups were fundamental to his success, according to Cosme. Among them were the people of Tlaxcala, who helped him regroup and take Tenochtitlán. "The Aztecs were not always popular rulers among their subjected cities. When Cortés learned of this, he was able to use this to his advantage," Cosme said. "Xicotencatl, a ruler in the city Tlaxcala, saw an ally in Cortés and an opportunity to destroy the Aztec Empire. They formed an allegiance, and Cortés was given several thousand warriors to add to his ranks. While the Spaniards still had superior weaponry — cannons, guns, swords — the additional knowledge on Aztec fighting styles and defenses given by Xicotencatl, plus the additional men, gave Cortés a helpful edge."

While Cortés held Tenochtitlán through Montezuma, a Spanish force from Cuba landed on the coast of Mexico in the spring of 1520. It had been sent by Velázquez to unseat Cortés. When Cortés heard of this, he took a force of Spanish and Tlaxcalan soldiers and marched on the new Spanish force, according to World History Encyclopedia. Cortés defeated the Spanish force, but when he returned to Tenochtitlán he found the Aztecs had launched a major attack on the Spanish garrison.

At first, Cortés tried to quell the attack by forcing Montezuma to address the Aztec forces that had gathered. But, by now, the Aztecs were distrustful of their king. In an event that is still debated by scholars, Montezuma was killed. It is unclear whether he was killed by his own forces — some accounts have him being stoned by his warriors — or by the Spanish, according to the Thought Company . In the Aztec accounts, Montezuma survives the attack by his warriors but is later strangled to death by the Spanish.

Cortés and his men fled the city. But their retreat was costly and they suffered significant losses, including most of the plunder they had stolen from the city.

However, the Spanish were there long enough to start a smallpox epidemic in Tenochtitlán. One of Cortés' men contracted smallpox from a member of the force from Cuba. That soldier died during the Aztec rebellion, and when his body was looted, an Aztec caught the disease, which spread like wildfire because the Aztec people had no immunity to it, according to History.com . Between one-quarter and one-half of the inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico, including Aztecs and other Native Americans, succumbed to the disease, according to Suzanne Alchon, a historian and author of the book A Pest in the Land, New World Epidemics in a Global Perspective (University of New Mexico Press, 2003).

With help from the people of Tlaxcala, Cortés' army regrouped and returned to Tenochtitlán on June 25, 1520. They found that the city's society had crumbled. Nonetheless, the Aztec warriors, under their new leader Cuauhtemoc, resisted the Spanish and a long siege ensued. Finally, after 93 days of siege, the Aztecs, weakened by disease, hunger and having incurred significant losses following many pitched battles, surrendered, according to World History Encyclopedia. This surrender unleashed a storm of violence, looting, rape and carnage as the Spanish and their Tlaxacalan allies descended on the city.

Once the city fell, Cortés began building Mexico City on the ruins. It quickly became a pre-eminent city in the Spanish colonies, and many Europeans came to live there. To reward his success, King Charles I of Spain appointed Cortés governor of New Spain.

The conquest of Mexico by the Spanish ended in 1525, though some Aztecs and their allies continued to resist the Spanish according to World History Encyclopedia . Nonetheless, the change to Spanish rule had massive and long-lasting consequences. Many of the Indigenous people were now forced into the role of subservience and a new, almost caste-like social order was created with the Spanish occupying the highest positions of power and the Indigenous people the lowest. This social dynamic would characterize Mexico for centuries.

In 1524, Cortés organized an expedition to Honduras, a part of central America that had not yet been conquered by the Spanish. He stayed for two years, establishing a city and appointing a governor, but when he returned to Mexico, he found that the allies he had left in Mexico City had turned against him, according to Britannica. He found himself removed from power, and accused of illegally enriching himself. Cortés traveled to Spain to plead with the king, but he was never again appointed to governorship. In Spain, he married for a second time, to a Spanish noblewoman named Dona Juana de Zuniga, a union that produced three children.

The king did allow him to return to Mexico, albeit with much less authority. Cortés explored the northern part of Mexico and discovered Baja California for Spain in the late 1530s. In 1540, he retired to Spain and spent much of his last years seeking recognition and rewards for his achievements.

Frustrated and embittered, Cortés decided to return to Mexico. Before he could go, however, he died in 1547 of pleurisy, an inflammation of the tissues that line the lungs and chest cavity.

Cortés is a controversial figure, especially in Mexico, because of his treatment of Natives. Unfortunately, "when it came to the Indigenous people, Cortés was not unique in his treatment and mindset," Cosme said. "He enslaved much of the Native population, and many of the Indigenous people were wiped out from European diseases such as smallpox. Both scenarios would unfortunately become a common theme among many explorers' interactions with Natives."

Nevertheless, Cortés was important in reshaping the world. "Cortés' victory secured new and profitable land and opportunities for the Spanish monarch. He helped oversee the building of Mexico City, which is still Mexico's capital today," Cosme said. "He opened the door for further exploration and conquest of Central America to the south, and eventually led to the acquisition of California toward the north."

Originally published on Live Science on Sept. 28, 2017 and updated on July 5, 2022.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.

- Tom Garlinghouse

Why do babies rub their eyes when they're tired?

Why do people dissociate during traumatic events?

Oldest canoes ever found in the Mediterranean Sea unearthed off the coast of Italy

Most Popular

By Anna Gora December 27, 2023

By Anna Gora December 26, 2023

By Anna Gora December 25, 2023

By Emily Cooke December 23, 2023

By Victoria Atkinson December 22, 2023

By Anna Gora December 16, 2023

By Anna Gora December 15, 2023

By Anna Gora November 09, 2023

By Donavyn Coffey November 06, 2023

By Anna Gora October 31, 2023

By Anna Gora October 26, 2023

- 2 Mass grave of plague victims may be largest ever found in Europe, archaeologists say

- 3 India's evolutionary past tied to huge migration 50,000 years ago and to now-extinct human relatives

- 4 1,900-year-old coins from Jewish revolt against the Romans discovered in the Judaen desert

- 5 Dying SpaceX rocket creates glowing, galaxy-like spiral in the middle of the Northern Lights

- 2 Watch bizarre video of termites trapped in 'death spiral'

- 3 'Potentially hazardous' asteroid Bennu contains the building blocks of life and minerals unseen on Earth, scientists reveal in 1st comprehensive analysis

- 4 Speck of light spotted by Hubble is one of the most enormous galaxies in the early universe, James Webb telescope reveals

- 5 8-hour intermittent fasting tied to 90% higher risk of cardiovascular death, early data hint

Hernán Cortés (1485-1547)

Cortés also spelled Cortéz Spanish conquistador who overthrew the Aztec empire (1519�21) and won Mexico for the crown of Spain.

Cortés was the son of Mart�n Cortés de Monroy and of Do�a Catalina Pizarro Altamarino—names of ancient lineage. "They had little wealth, but much honour," according to Cortés's secretary, Francisco López de Gómara, who tells how, at age 14, the young Hernán was sent to study at Salamanca, in west-central Spain, "because he was very intelligent and clever in everything he did." Gómara went on to describe him as ruthless, haughty, mischievous, and quarrelsome, "a source of trouble to his parents." Certainly he was "much given to women," frustrated by provincial life, and excited by stories of the Indies Columbus had just discovered. He set out for the east coast port of Valencia with the idea of serving in the Italian wars, but instead he "wandered idly about for nearly a year." Clearly Spain's southern ports, with ships coming in full of the wealth and colour of the Indies, proved a greater attraction. He finally sailed for the island of Hispaniola (now Santo Domingo) in 1504. He was then 19.

Years in Hispaniola and Cuba

In Hispaniola he became a farmer and notary to a town council; for the first six years or so, he seems to have been content to establish his position. He contracted syphilis and, as a result, missed the ill-fated expeditions of Diego de Nicuesa and Alonso de Ojeda, which sailed for the South American mainland in 1509. By 1511 he had recovered, and he sailed with Diego Velázquez to conquer Cuba. There Velázquez was appointed governor, and Cortés clerk to the treasurer. Cortés received a repartimiento (gift of land and Indian slaves) and the first house in the new capital of Santiago. He was now in a position of some power and the man to whom dissident elements in the colony began to turn for leadership.

Cortés was twice elected alcalde ("mayor") of the town of Santiago and was a man who "in all he did, in his presence, bearing, conversation, manner of eating and of dressing, gave signs of being a great lord." It was therefore to Cortés that Velázquez turned when, after news had come of the progress of Juan de Grijalba's efforts to establish a colony on the mainland, it was decided to send him help. An agreement appointing Cortés captain general of a new expedition was signed in October 1518. Experience of the rough-and-tumble of New World politics advised Cortés to move fast, before Velázquez changed his mind. His sense of the dramatic, his long experience as an administrator, the knowledge gained from so many failed expeditions, above all his ability as a speaker gathered to him six ships and 300 men, all in less than a month. The reaction of Velázquez was predictable; his jealousy aroused, he resolved to place leadership of the expedition in other hands. Cortés, however, put hastily to sea to raise more men and ships in other Cuban ports.

The expedition to Mexico

When Cortés finally sailed for the coast of Yucatán on February 18, 1519, he had 11 ships, 508 soldiers, about 100 sailors, and—most important—16 horses. In March 1519 he landed at Tabasco, where he stayed for a time in order to gain intelligence from the local Indians. He won them over and received presents from them, including 20 women, one of whom, Marina ("Malinche"), became his mistress and interpreter and bore him a son, Mart�n. Cortés sailed to another spot on the southeastern Mexican coast and founded Veracruz, mainly to have himself elected captain general and chief justice by his soldiers as citizens, thus shaking off the authority of Velázquez. On the mainland Cortés did what no other expedition leader had done: he exercised and disciplined his army, welding it into a cohesive force. But the ultimate expression of his determination to deal with disaffection occurred when he burned his ships. By that single action he committed himself and his entire force to survival by conquest.

Cortés then set out for the Mexican interior, relying sometimes on force, sometimes on amity toward the local Indian peoples, but always careful to keep conflict with them to a strict minimum. The key to Cortés's subsequent conquests lay in the political crisis within the Aztec empire; the Aztecs were bitterly resented by many of the subject peoples who had to pay tribute to them. The ability of Cortés as a leader is nowhere more apparent than in his quick grasp of the situation—a grasp that was ultimately to give him more than 200,000 Indian allies. The nation of Tlaxcala, for instance, which was in a state of chronic war with Montezuma, ruler of the Aztec empire of Mexico, resisted Cortés at first but when defeated became his most faithful ally. Rejecting all of Montezuma's threats and blandishments to keep him away from Tenochtitlán or Mexico, the capital (rebuilt as Mexico City after 1521), Cortés entered the city on November 8, 1519, with his small Spanish force and only 1,000 Tlaxcaltecs. Montezuma, believing him to incarnate the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl, received him with great honour. Cortés soon decided to seize Montezuma in order to hold the country through its monarch and achieve not only its political conquest but its religious conversion. Marina worked on the complicated, enigmatic mind of Montezuma so subtly that he finally became the voluntary prisoner of her master. With this stroke Cortés became the master of Tenochtitlán.

Spanish politics and envy, however, were to bedevil Cortés throughout his meteoric career. Cortés soon heard of the arrival of a Spanish force from Cuba, led by Pánfilo Narváez, to deprive Cortés of his command at a time (mid-1520) when he was holding the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán by little more than the force of his personality. Leaving a garrison in Tenochtitlán of 80 Spaniards and a few hundred Tlaxcaltecs commanded by his most reckless captain, Pedro de Alvarado, Cortés marched against Narváez, defeated him, and enlisted his army in his own forces. On his return, he found the Spanish garrison in Tenochtitlán besieged by the Aztecs after Alvarado had massacred many leading Aztec chiefs during a festival. Hard pressed and lacking food, Cortés decided to leave the city by night. The Spaniards' retreat from the capital was performed, but with a heavy loss in lives and most of the treasure they had accumulated. After six days of retreat Cortés won the battle of Otumba over the Aztecs sent in pursuit (July 7, 1520).

Cortés eventually rejoined his Tlaxcalan allies and reorganized his forces before again marching on Tenochtitlán in December 1520. After subduing the neighbouring territories he laid siege to the city itself, conquering it street by street until its capture was completed on August 13, 1521. This victory marked the fall of the Aztec empire. Cortés had become the absolute ruler of a huge territory extending from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean.

In the meantime, Velázquez was mounting an insidious political attack on Cortés in Spain through Bishop Juan Rodr�guez de Fonseca and the Council of the Indies. Fully conscious of the vulnerability of a successful conqueror whose field of operations was 5,000 miles (8,000 km) from the centre of political power, Cortés countered with lengthy and detailed dispatches—five remarkable letters to the Spanish king Charles V. His acceptance by the Indians and even his popularity as a relatively benign ruler was such that he could have established Mexico as an independent kingdom. Indeed, this is what the Council of the Indies feared. But his upbringing in a feudal world in which the king commanded absolute allegiance was against it.

Later years

In 1524 his restless urge to explore and conquer took him south to the jungles of Honduras. The two arduous years he spent on this disastrous expedition damaged his health and his position. His property was seized by the officials he had left in charge, and reports of the cruelty of their administration and the chaos it created aroused concern in Spain. Cortés's fifth letter to the Spanish king attempts to justify his reckless behaviour and concludes with a bitter attack on "various and powerful rivals and enemies" who have "obscured the eyes of your Majesty." But it was his misfortune that he was not dealing simply with a king of Spain but with an emperor who ruled most of Europe and who had little time for distant colonies, except insofar as they contributed to his treasury. The Spanish bureaucrats sent out a commission of inquiry under Luis Ponce de León, and, when he died almost immediately, Cortés was accused of poisoning him and was forced to retire to his estate.

In 1528 Cortés sailed for Spain to plead his cause in person with the king. He brought with him a great wealth of treasure and a magnificent entourage. He was received by Charles at his court at Toledo, confirmed as captain general (but not as governor), and created marqués del Valle. He also remarried, into a ducal family. He returned to New Spain in 1530 to find the country in a state of anarchy and so many accusations made against him—even that he had murdered his first wife, Catalina, who had died that year—that, after reasserting his position and reestablishing some sort of order, he retired to his estates at Cuernavaca, about 30 miles (48 km) south of Mexico City. There he concentrated on the building of his palace and on Pacific exploration.

Finally a viceroy was appointed, after which, in 1540, Cortés returned to Spain. By then he had become thoroughly disillusioned, his life made miserable by litigation. All the rest is anticlimax. "I am old, poor and in debt . . . again and again I have begged your Majesty. . . ." In the end he was permitted to return to Mexico, but he died before he had even reached Sevilla (Seville). (Ralph Hammond Innes, Encyclopaedia Britannica Article)

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

The Old World Soldier Who Conquered the New

For the sick, half-starved inhabitants of Tenochtitlán, island capital of the beleaguered Aztec empire, the new year of 1521 offered only severe hardship and continued bloodshed. Over the past eight months the city’s quarter million residents had suffered through the deaths of two emperors, Montezuma II and his brother Cuitláhuac; the loss of the entire upper echelon of the empire’s military and political elites to a cowardly Spanish massacre; and a 70-day scourge of smallpox that killed tens of thousands and claimed Cuitláhuac’s life, on December 4. His nephew Cuauhtémoc, as 11th Aztec emperor (known as the huey tlahtoani , or “great speaker”) and commander in chief, was left to defend the city against a coalition army of aggrieved Indians and determined Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés .

After reaching Hispaniola in 1506, Cortés prospered in the West Indies. Several years of civil service in Cuba, in the wake of its 1511 conquest by Diego Velásquez de Cuéllar, had earned him an encomienda , a large estate complete with thousands of indigenous laborers compelled to work in mining and agriculture. Appointed governor of Cuba, Velásquez was planning to finance his own campaign of conquest on the mainland of Mexico when he sent his secretary, Cortés, on a limited mission to explore the coast in 1519. Cortés and several veteran officers, however, opted to pursue a far more ambitious, albeit unsanctioned, undertaking—the expansion of the Spanish empire into Mexico and beyond, in the name of Christianity, while acquiring vast wealth, land and renown for themselves.

Disembarking at Tabasco on March 12, Cortés and 630 Spaniards moved inland and encountered the Mayans of Potonchán, who answered his request for talks with torrents of arrows, spears and stones that had little effect on Spanish armor. Facing overwhelming numbers, Spanish soldiers armed with harquebuses, crossbows, pikes and steel swords and accompanied by heavy artillery, mounted lancers and war dogs routed some 10,000 attackers, after which the defeated Mayans provided Cortés with 20 women slaves, among them the Nahuatl-speaking Malinche, who became Cortés’ invaluable interpreter, consort and mother of his first son.

Sailing north along the coast, the Spaniards came ashore near San Juan de Ulúa on April 21 and, in a veiled attempt to legitimize their expedition, founded a new colony at Veracruz “in His Majesty’s name.” Cortés then marched north to Cempoala, home to the Totonacs, where for the first time the conquistador leader moved to exploit a tributary population’s bitterness toward Tenochtitlán. Resentful subjects of the empire since 1480, the Totonacs forged an alliance with Cortés, who directed them to cease paying tribute, which could include military service, gold, foodstuffs, trade goods or captives (some of the latter were enslaved, while others were ritually sacrificed and eaten). After scuttling all but one of his ships (which sailed for Spain carrying slaves and treasure to be presented to Charles V, king of Spain and Holy Roman emperor), Cortés pushed inland on August 16 accompanied by 800 Totonac warriors.

Cortés and his host had barely entered Tlaxcalan territory when they were ambushed by a disciplined force of warriors led by their commander in chief, Xicotencatl the Younger. Home to upward of 150,000 people, Tlaxcala was a confederation of four hill provinces united against their Aztec archenemies in Tenochtitlán, who for decades had oppressed them with embargoes on salt, gold and cotton and demands for captives as tribute. After several clashes with the Spaniards, Xicotencatl the Elder and the city’s other lords halted hostilities and invited Cortés into their capital on September 23. Awed by the expedition’s horses and gunpowder weapons, Xicotencatl the Elder, who like Cortés was looking for powerful allies, agreed to an alliance (see “The Warriors Who Nearly Destroyed Cortés—Before Joining Him,” by Justin D. Lyons, online at HistoryNet.com).

this article first appeared in Military History magazine

On November 8, with 2,000 Tlaxcalan warriors, porters, guides and cooks added to the Spanish ranks (the Totonacs had returned home), Cortés boldly marched into Tenochtitlán, where Montezuma extended the Spaniards a diplomatic if wary welcome. A week later events on the Gulf of Mexico gave Cortés a pretext to act. After Aztec tax collectors in the town of Nauhtla demanded local Totonacs pay their customary tribute and were refused, fighting broke out, and the Aztecs slew several Spaniards and Totonacs. Accusing Montezuma of collusion in the bloodshed, Cortés brazenly arrested the stunned emperor and ordered him to reside in the Spanish quarters under guard. After getting assurances of his safety from Malinche, the shaken emperor acquiesced, allowing Cortés to usurp his host and take effective control of the city for the next six months.

The Spaniards had amassed eight tons of looted gold and silver when, with Cortés absent from the city, his deputy, Pedro de Alvarado, led an unprovoked attack against celebrants at the Festival of Toxcatl, hacking to death hundreds of senior military and political leaders and their families. The atrocity touched off a violent citywide revolt that trapped the Spanish/Tlaxcalan forces inside their quarters under a rain of spears, stones and arrows from surrounding rooftops. Cortés returned on June 24, 1520, to find Alvarado’s actions had put the entire expedition in peril, leaving the Spaniards no choice but to flee the city with their sick, wounded, artillery and treasure in tow.

At midnight on the rainy night of June 30, Cortés led his assembled host—1,300 Spaniards and 2,000 allies—from Tenochtitlán onto the Tacuba causeway, heading west out of the city. The van had marched but a quarter mile along the causeway when the escape attempt was discovered. Hundreds of canoes soon filled surrounding Lake Texcoco, bringing the long column strung out along the span under withering missile fire while warriors streamed out of the city on foot to attack the column from the rear. After six terrifying hours Cortés and other survivors stumbled ashore, having lost as many as 800 Spaniards and more than 1,000 allies killed, captured or drowned, along with most of the horses and all the gunpowder, cannons and treasure.

Incredibly, the crushing defeat—recorded by the Spanish as La Noche Triste (“The Night of Sorrows”)—wasn’t enough to convince the redoubtable Cortés to abandon the campaign. Most of his veteran captains and mounted lancers, his interpreter, Malinche, and shipwright Martin López, the one man who could construct new warships for a return assault on Tenochtitlán, had survived the carnage. Gathering his wounded, hungry forces—about 500 Spaniards and 800 Tlaxcalans—Cortés led the small band 150 miles through hostile territory armed only with swords, crossbows, lances and pikes, reaching Tlaxcalan territory on July 9.

As Cortés himself recovered from a fractured skull, his fortunes turned for the better. Xicotencatl the Elder refused Cuauhtémoc’s offer of tribute relief and instead agreed to a new “perpetual alliance” with Cortés, while supply ships from Spain and Cuba—the Crown having dismissed mutiny charges against the expedition leader—arrived at Veracruz laden with men, horses, weapons, gunpowder and provisions. In August, backed by 2,000 loyal Tlaxcalans, Cortés captured the mountaintop redoubt of Tepeaca, a critical Aztecan ally, then used it as a base to subdue the surrounding villages. Some towns submitted voluntarily. Others were sacked, their male populations executed, their women and children branded and sold into slavery. By autumn 1520 Cortés was the strongest entity in the vast flatlands between the Popocatépetl and Pico de Orizaba volcanoes and had effectively cut off Tenochtitlán from the Gulf of Mexico. Before leaving Tepeaca, Cortés tasked López with constructing a fleet of 13 brigantines at Tlaxcala using native labor and salvaged hardware, after which the finished ships would be dismantled, carried over the mountains, reassembled and launched on Lake Texcoco.

Intent on first subduing the cities ringing the lake, Cortés gathered 550 Spanish infantry, 40 horsemen and 10,000 handpicked Tlaxcalans and in late December 1520 marched for Texcoco, still nominally an Aztec ally. As the Spaniards approached, they were met by emissaries from rebel Texcocan warlord Ixtlilxochitl II, who joined the advance with his own warriors and thousands of canoes. Arriving at Texcoco, Cortés and his growing force found it virtually abandoned, its tlahtoani and citizens having fled across the lake to Tenochtitlán. After sacking the city, Cortés pronounced Ixtlilxochitl Texcoco’s new tlahtoani , at a stroke bloodlessly adding another powerful ally to his ranks. The consequent Aztec loss of Texcoco, with its bountiful harvests and strategic location on the lake’s eastern shore, was a crippling blow to Tenochtitlán. As occurred at Tepeaca, the Spaniards’ success compelled the lords of neighboring cities to visit Cortés’ camp and offer their allegiance.

In early January 1521, on learning that Chalca cities south of the lake were restive, Cortés led 200 Spaniards and 4,000 allies to sack Iztapalapa, while his lieutenant Gonzalo de Sandoval evicted Aztec garrisons from Chalco and Tlamanalco, loosening Tenochtitlán’s grip on the region. At the urging of his two powerful allies, Cortés further isolated Tenochtitlán by subduing Tlacopán, the last city-state of the Aztec Triple Alliance. (In 1427–28 Itzcoatl, the fourth Aztec emperor, had led Tenochtitlán, Texcoco and Tlacopán to decisive victory in their rebellion against Azcapotzalco, after which the victors had formed the Triple Alliance to share in future wars of conquest. By 1519, after nearly a century of aggressive expansion, the alliance was dominated by Tenochtitlán, its borders stretching from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico south almost to Guatemala, which extracted tribute from nearly 500 cities and towns in the Valley of Mexico and beyond, backed by the constant threat of military force.)