An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Present-Day Mass Tourism: its Imaginaries and Nightmare Scenarios

Utrecht, Amsterdam The Netherlands

Present-day mass tourism uncannily resembles an auto-immune disease. Yet, self-destructive as it may be, it is also self-regenerating, changing its appearance and purpose. They are two modes that stand in contrast to each other. We can see them as opposites that delimit a conceptual dimension ordering varieties of present-day mass tourism. The first pole calls forth tourism as a force leaving ruin and destruction in its wake or at best a sense of nostalgia for what has been lost, the other sees tourism as a force endlessly resuscitating and re-inventing itself. This paper article highlights both sides of the story. These times of the Covid-19 pandemic, with large swathes of public life emptied by social lock-down, remind us of a second, cross-cutting conceptual dimension, ranging from public space brimming with human life to its post-apocalyptic opposite eerily empty and silent. The final part of my argument will touch on imagined evocations of precisely such dystopian landscapes.

This is what present-day tourism has brought us. As Oliver Hardy would have it, in one of the many films starring him and Stan Laurel: Another nice mess you got us into. Photographs amply illustrate this. They show us the congestion, even back-ups, en route to the top of Mount Everest. Or the dense forest of outstretched arms and selfie sticks that prevent us from seeing eye to eye with Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. They show all these cruise ships, ready to sail from Venice, New Orleans and other such ports-of-call, holding out the promise of fulfillment of our innermost private dreams and longings. Among them the classic dream that inspired travel in the days of the “grand tour,” seen as part of the education of aristocrats, of either noble or moneyed background, the elite of the happy few of their time. In today’s mass tourist version, all such dreams have been subverted and turned into their nightmarish opposite. Hordes of tourists now swoop down on places never meant to cope with their numbers. It may remind us of Henry James’s sense of horror when confronted with the mass of immigrants setting foot on Ellis Island. In The American Scene, written following a return visit to his native country and presenting a view of America seen through the eyes of the quasi-European that James had become, he compared the influx of immigrants to a “visible act of ingurgitation on the part of our body politic and social.” He goes on to ponder “the degree to which it is his American fate to share the sanctity of his American consciousness, the intimacy of his American patriotism, with the inconceivable alien … an apparition, a ghost, … in his supposedly safe old house.” 1 This is an apt description of what inhabitants of today’s tourist destinations, ago-old port cities like Venice or Amsterdam, must be feeling in the face of the hordes of visitors dumped by one cruise ship following another. Admittedly, the visitors today are tourists, not immigrants, but they must strike a Jamesian sensibility in similar ways. And according to alarmed newspaper reports local resistance and protest in tourism’s most favored places is growing apace. The current buzzword in city government circles is over-tourism. As a piece in Atlantic magazine on “the Dutch war on tourists” put it: “The Dutch have suffered some brutal occupations, from the Roman empire and Viking raids to Spanish and Nazi rule. But now they face an even larger army of invaders: tourists.” 2 In the era of cheap flights and Airbnb, their numbers are staggering. Some 19 million tourists visited the Netherlands last year, more people than live there. For a country half the size of South Carolina, with one of the world’s highest population densities, that is a lot. The problem for Amsterdam, in its starkest form, is a matter of survival as a working, residential city, rather than as a playground for tourists to trample underfoot. Venice may be closer to meeting that fate, with its residential population dwindling. And so may New Orleans after Katrina. In New Orleans: An American Pompeii? , Lawrence N. Powell demonstrates that the rebuilding of New Orleans’ infrastructure, which had been long due for an extreme makeover, is in danger of crossing over the fine line separating opportunity from opportunism, whether it be the opportunism of commercialism or racism or a combination of the two. The recovery of New Orleans, as Powell argues, may have resulted in one of those ‘lost cities’, like Pompei, that have been restored solely as sites of tourism and myth. 3

Present-day mass tourism uncannily resembles an auto-immune disease. In a fevered feeding frenzy, it turns in upon itself eating away at the very tissue meant to be preserved. Like locusts swarming, tourism is seasonal, swooping down, leaving devastation in its wake. Yet, self-destructive as it may be, it is also self-regenerating, changing its appearance and purpose. The destruction side of the story I will tell here relates to an iron law in economics, the commodification paradox: there are things that by general consent are deemed of high intrinsic value yet are inconsistent with the economic logic of price and exchange value, or for that matter, the conceptual universe of economic goods and commodities. Once exposed to that logic, they vanish like snow melting in the sun. By way of examples, we need only think of exquisite geographic spots or authentic historic settings and see them vanish forever when opened to consumption by the many. The other half of my story offers redemption, in a post-modern vein. It explores the imitative behavior of tourists seeking reiterations of pleasures they have seen or heard described, if not vicariously experienced through mass advertising. Here the main vector of tourist behavior is not the quest for the pristine and virginal, but rather the urge to do as others did, and to join the multitudes who went before, all engaging in such acts of quasi-individuation as taking a selfie as proof of one’s presence. The ultimate self-ironizing version – post-modern before its time - is the classic graffiti telling us that “Kilroy was here”. Well, he wasn’t; yet clearly someone was wishing to leave proof of presence, tongue-in-cheek, in an implied wink to the many Kilroys yet to come. Clearly these two modes of tourist pleasure stand in contrast to each other. We can see them as opposites that delimit a conceptual dimension ordering varieties of present-day mass tourism. One polar end we may call – in an echo of a 1910s’ cliffhanger film series, The Perils of Pauline – “the perils of pristine.” The other end we shall call “the pleasures of post-modernity.” The first pole, then, calls forth tourism as a force leaving ruin and destruction in its wake or at best a sense of nostalgia for what has been lost, the other sees tourism as a force endlessly resuscitating and re-inventing itself.

The Perils of Pristine

There may be no better way to illustrate the tragic paradox inherent in the human enjoyment of the pristine than the case of George Bird Grinnell, prominent early American conservationist. He had made it out West just in time to watch one era fade into another, on the eve of the Transcontinental Railroad opening the West to the many interests that had been eagerly eying it, and before Buffalo Bill’s mastery at turning contemporary history into the stuff of spectacle and mass entertainment had begun to re-write the epic of the West. Grinnell was among those who had an early awareness of the need, if not the moral duty, to preserve natural habitats and wildlife. Perhaps his greatest legacy is Glacier National Park in Montana, which he did more than anyone else to help protect, and where Mt. Grinnell now looks down on Grinnell Glacier. By the time of his last trips, in the 1920s, it was no longer the wild place he had first encountered. As he wrote to the soon-to-be-famous young conservationist Aldo Leopold, “While I have never regretted what I did in this matter because of the pleasure those parks give to a vast multitude of people, still the territory that I used to love and travel through is now ruined for my purposes.” 4 This tragic awareness that the democratic sharing of his pleasures inescapably ruined them “for his purposes” lies at the heart of the conundrum that I flippantly call the perils of pristine.

Yet, undeniably, one perennial force moving people temporarily to leave home and hearth and go out into the wider world is the urge to explore and discover, to go where no-one has gone before, in hopes of striking upon the terrestrial paradise. And more than that, upon their return home, to engage in the games of one-upmanship that we all play, bragging about that pristine little beach or that bucolic little restaurant off the tourist track. We thus feed the mass reservoir of tourist longing, keeping people leafing through the pages of travel magazines, with one tantalizing view after another of places untouched by tourism. As one such magazine promises: We create memories. Rather a sophisticated view, in fact, coming as it does from a travel agency. For indeed: rather than promising novel experiences and new discoveries, the slogan anticipates the next stage: the translation of travel experiences into memories. Memories which we then share with others, leading them to follow in our footsteps – finding that pristine beach, that recondite little restaurant. Rather than creating memories it has become a matter of re-creation , in whichever sense of that word. Those following in our footsteps re-create our memories while making them their own. This is how tourism translates into a mass phenomenon, turning private memories into commodities advertised and held up for imitation. Peddling what are basically second-hand goods tourism endlessly recycles the standard tourist fare, boosting tourist numbers while ruining what made the tourist herds flock together in the first place. We may call the driving force here, in a Freudian vein, memory envy. The travel agenda in such cases is essentially of this type: Been there, Seen it, Done that. It has become a matter of ticking off places to go, to see, and produce a selfie. Today’s travel destinations are literally “lieux de mémoire”, to be visited before they are remembered, placed on the map by other people’s memories.

Things are different in the case of nostalgia. If memory still plays a role, it is the remembrance of things past, or more crucially of things irretrievably lost, yet awaiting their re-imagining. The setting is Proustian rather than Freudian. If it calls for travel, it is time travel, temporal and imaginary, rather than geographical. It can be done as an act of individual imagination, without ever leaving one’s armchair. One can, for instance, sit listening to Aaron Copland’s music, such as his Rodeo , while before one’s mind’s eye a film screen is widening to vast panoramas of the American West. If this is travel, it is a matter of the power of our imagination. Yet, in today’s world, our every wish can be accommodated by the market, and time travel now fills pages of tourist guides. If with the advent of the U.S. Interstate system, from the late 1950s on, fabled stretches of highway like Route 66 lost their raison d’être, and were left for weeds to take over, stretches are now – nostalgically – put back into use. Tourists from the US and Europe, their heads filled with Western imagery, from wide-screen cinema, songs from musicals, photographs, are now catered for with organized tours. They will find their Harley Davidsons waiting and off they go, in search of an America gone forever, yet now to be nostalgically revived. Route 66 has been re-invented as our collective present-day memory lane.

Examples abound of this happening. Civil-War battle fields, with historical re-enactments thrown in to the hearts’ content of visiting history buffs, the Appalachian Trail, freshly done up, with the added bonus of Bill Bryson’s dry wit reporting on his revisit of the trail, Crevecoeur’s travels in America as revisited in Jonathan Raban’s Hunting Mister Heartbreak , immersions in the history of railroad hotels like the Posada Hotel in Winslow Arizona (while hearing in one’s head the lyrics of “Standing on a corner in Winslow Arizona,” sung by the Eagles), or a stay at mountain resorts such as Bretton Woods, feeling the spectral presence of great minds like Lord Keynes’s putting together the pieces of a new world order in the mid-1940s. 5 Such imaginary time travel is probably what the great Dutch historian Johan Huizinga had in mind when he tried to find words for the historic epiphany he experienced when entering Cologne cathedral from the bustling city center, in pre-World-War II days. To Huizinga it felt like stepping back into the peace and quiet of the Middle Ages. Time seemed to fall away. He described it as the quintessence of the experience of history, as an act almost of world renunciation in exchange for the order of the monastic, medieval world.

A contemporary version of this quest for sites of nostalgia is the Spa, the Grand Hotel, the fabled watering holes across the map of Europe, playground and meeting place for the international upper crust. They are sites of nostalgia today, remnants of a past long gone, vanished along with the “Belle époque” whose outward face they represented. Yet at the same time, vanished they may be, they refuse to be laid to rest. A cultural revival is afoot, in books and films, opening the doors of the past to our nostalgic promptings. The prime exhibit may well be a cinematic masterpiece, Russian Ark , from 2002. In one uninterrupted, long take – a technical tour de force – the director, Alexander Sokurow, takes us through three centuries of Russian history, set in the labyrinthine maze of the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. If this already is a trip that no travel agency can rival, the concluding moments give form and face to the process of history turning into instant nostalgia. While a magnificent ball is coming to an end and the many guests start flowing down the stairways, the camera wanders off to a door opening on the river Newa, with mist rolling in. It is an ominous closing image of an era coming to and end, engulfed by forces of darkness. It appears as if nostalgia for an era closing forever is shown here at the point of its formation.

In this general vein of nostalgic revisits to memory sites, a few more cases bear mentioning. The Grand Hotel as an emblem of a European cultural era has been stunningly brought back to life in Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), with all the sense of decorum, punctilious rituals, and deference to status differentials. It is the world that that quintessential central-European author Stefan Zweig conjured up in Die Welt von gestern ( The World of Yesterday ), the book he wrote in self-chosen exile in Brasil in 1942. 6 He committed suicide there, while his beloved Europe succumbed to Nazi totalitarianism. Wes Anderson dedicated his film to the memory of Zweig. More than that, he has Zweig make a fictional appearance in the closing scenes of the film, where he is shown reminiscing with the hotel’s current owner about his predecessor, Monsieur Gustave, the man who had truly embodied the world of the Grand Budapest Hotel. Although, as his successor clarifies, it had not even been Monsieur Gustave’s world: “His world? No, his world had vanished before he ever entered it. He certainly sustained the illusion with marvelous grace.” So, in this game of ever receding illusions, the true spirit of nostalgia is beautifully captured, and shown as the mirage it is.

Using a different medium, the novel rather than film, Dutch novelist Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer added to the metaphoric power of the Grand Hotel as standing for a certain idea of Europe when he called his latest novel Grand Hotel Europe (2019). 7 Rather than an attempt at revival, though, showing a European cultural era at full swing, it catches it as it fades away, as in a yellowing old photograph. The hotel guests are like assorted relics from a bygone era. The novel’s protagonist seeks refuge among them to lick his wounds after the break-up of a relationship with Clio, an Italian art historian named after the Greek muse of history. The sense of things coming to an end, winding down, pervades the novel. More than anything it conjures up Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain or Death in Venice , stations for the terminally ill rather than sites of excitement. The prevailing mood in Grand Hotel Europe is of decay rather than decadence, seeing entropy, a terminal winding down, in the bustle of tourism and travel. As the few remaining resident guests at the Grand Hotel Europe look at it, travel and tourism, in their present-day iteration, are forces of destruction.

When Clio and the novel’s protagonist were still together, during a visit to the Castello Mackenzie in Genoa, a nineteenth-century fantasy structure erected in mock Florentine renaissance style, their conversation touches on the theme of authenticity and its replica versions. Castello Mackenzie, fake when it was built, a nostalgic dream come true, had since been put on the list of protected architectural monuments. As Clio puts it: “This is nostalgia squared, a quadratic version of it.” Both agree that it will never be the real thing, never be truly old. The writer then adds “I think it is our European blood. This way of thinking typifies us Westerners. It is the curse of the old continent. … You could summarize the history of Europe as a history of the continued longing for history.” If the remembrance of things past constitutes the dreams we dream today, nostalgia will be the defining element of our outlook on life. And as for the quest for authenticity, taking the Mona Lisa as an example, the writer has this to say: “What matters is that people want to see the Mona Lisa not for the sake of the experience of seeing her in reality. What matters is what Walter Benjamin called the aura of the work of art. Or rather, not so much the work of art itself, but the sensation of being up close to it, preferably stamped with the seal of authenticity of a photograph or a selfie.” (63, 113).

We’ll leave Pfeijffer on this ironically deconstructionist view of present-day tourism. He is keenly aware of Europe as a stage for global tourism, caught in an existential battle between the urge to preserve an authentic cultural heritage, while seeing it buckle under when confronted with the many in their quest for the real thing. He also repeats a point made by others before him, by observers such as Umberto Eco or Jean Baudrillard, that often the fake is to be preferred to the real thing, the simulacrum to the authentic version. Europe’s crumbling cultural heritage is to be admired many times over in the U.S., in Las Vegas and other such places. And what is more, Europe has jumped on the bandwagon, repackaging itself in Disney-like tourist versions, for bus loads of Chinese tourists to behold and capture on cellphones. There is a hilarious TV documentary on this, made over a decade ago: Theme Park Holland ( Pretpark Nederland ). 8

Here too the hungry beast of commercial mass tourism has discovered the value and attraction of nostalgia. It has moved up-market to cater for the tastes of tourist snobs (who will never admit to this). It now offers upscale nostalgic tours while packaging and selling the authentic historical experience. High-brow newspapers now offer city tours, 25 days, all-in, with expert guides, and the odd afternoon lecture on board the cruise ship, to places ranging from San Francisco and New York, to Athens and Berlin. They are on tantalizing display in the ads, ready for consumption. Been there, done that. The true spirit of history, the historical experience, is nowhere to be had. “Just follow the guide, please.” To visitors and locals alike, the effect is the same. To residents the place is no longer theirs, to visitors, authenticity is nowhere to be found. As Tony Perrottet, author of Pagan Holiday , who lives in Manhattan, put it: “God, there’s nothing more annoying than getting stuck on Fifth Avenue between a bunch of tourists.” 9 Yet, according to him, anti-tourist sentiment can be traced at least as far back as the first and second centuries A.D., when wealthy Romans visited Greece (where they complained about the food), Naples (where they complained about the guides), and Egypt (where they defaced the pyramids and the Sphinx with graffiti). “The structure of tourism historically is that you have resentful locals, and rich, obnoxious, clueless intruders: the Greeks and the Romans, the Brits and the Americans, the Dutch and Germans.” 10 This may suggest there being a deep structure to the trials and tribulations visited equally upon tourists and their locales over the ages. If so, it is a far cry from a more reflective mental attitude, characteristic of the traveler more than the tourist. It may put us in mind of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s ruminations in his Tristes Tropiques (first published in 1955). Reminiscing on his peregrinations as a researcher and traveler, he describes himself as “an archeologist of space, seeking in vain to recreate a lost local colour with the help of fragments and debris.” It inspires the following lament: “I wished I had lived in the days of real journeys, when it was still possible to see the full splendour of a spectacle that had not yet been blighted, polluted and spoilt.” In other words, a spectacle that had managed to stay pristine, untouched by the march of time and the ruins of tourism. Yet, as Lévi-Strauss then acknowledges, this view of things creates a false binary, suggestive of a before and after, falsely imposing a view of history as a matter of static formations succeeding each other rather than as an ongoing transformative process. “While I complain of being able to glimpse no more than the shadow of the past, I may be insensitive to reality as it is taking shape at this very moment.… A few hundred years hence … another traveller, as despairing as myself will mourn the disappearance of what I might have seen, but failed to see.” 11

In this vein, moving now to the second part of my argument, the challenge before us will be to avoid the trap as sketched here by Lévi-Strauss and to take a fresh look at tourism as it changes shape before our eyes.

The Pleasures of Post-Modernity

“Historical marker ahead.” Driving along America’s highways and by-ways we pass many such signs. I for one always duly stop, curious to find out what local boosters have deemed worthy of a fleeting moment’s reflection by transient travelers. That is all as it should be. Hardly ever has a historical marker served to create a true “lieu de mémoire.” Places thus marked sink back into oblivion the moment we step on the gas again. Yet, at times, the marker may become more than the impassive purveyor of tidbits of knowledge and speak to us in the active voice of a participant in history. Or shall we say: a silent witness.

A telling case is that of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year old black Chicago youngster, who when visiting his uncle in the Mississippi Delta, in 1955, was viciously murdered by whites in retaliation for allegedly having wolf-whistled at a white female shop assistant. It became one of the moments that helped to launch the Civil Rights movements in the late 1950s. Certainly a moment worthy of a historical marker. Yet rather than becoming a token of remembrance, bringing reconciliation, it drew the ire of local white supremacists, who vented their anger on the monument. In its present iteration it is the fourth marker on the spot where Emmett Till’s mutilated body was drawn from the waters. Previous markers were stolen, thrown in the river, replaced only to be riddled with bullet holes, cut down, replaced again, shot up again. The new memorial weighs 500 pounds and is made of reinforced steel covered in bullet-proof glass. It is surrounded by security cameras. Two weeks after having been put in its place six white men and two women gathered there. One carried the flag of a group called the League of the South, which advocates for “Anglo-Celtic” supremacy. Its founder, Michael Hill, said: “We are at the Emmett Till monument that represents the civil-rights movement for blacks. What we want to know is: when are all of the white people over the last fifty years that have been murdered, assaulted and raped by blacks going to be memorialized?” When the security cameras picked up the protest and triggered an alarm, the protesters ran away.

Just sixteen miles south lies Glendora, a small town that houses the largest collection of memorials, including an Emmett Till museum. Glendora is one of the poorest towns in the impoverished Mississippi Delta. There is even an NGO devoted to combating poverty in – mind you – Haiti, Guatemala, Peru – and Glendora. In 2009 the Mississippi Development Authority sent a team of economists to the town. After describing it as a place with “no hope,” they said its only viable asset was civil-rights tourism. In an utter twist of irony, the hope now is to bring tourists to a place meant to commemorate the plight of blacks and their civil rights struggles and to pay their respects to the historic victims of racism, when in fact the place more easily rallies its evil perpetrators.

All in all, this is not the sort of story that your average roadside historical marker has in store. If a marker put up in Glendora would tell a story, it would be a never-ending story, with no clear end in sight, no upward slope, no light at the end. If it conjures up a past nostalgically remembered, it is the wrong past of racism and white supremacy. If there is anything postmodern about this, it must be in its mass-media iterations, with a current president as ringleader who sees “good people on both sides,” and to whom there is an equivalence on all sides of moral issues. There may in fact, under America’s present political leadership, be a vast moral erosion at work, leaving everything morally polyvalent, equally plausible, equally capable of being turned into mass entertainment.

As for tourism and the urge to travel and trade places, a similar erosion may be at work. Like moral issues in the public realm tourist destinations have likewise become interchangeable, open to the total make-over that the masters of mass manipulation can give them. Exclusivity is simply a matter of claiming it in the face of mass-produced uniformity, as Don de Lillo describes his students entering to attend class: “They came in out of the sun in their limited-edition T-shirts.” Limited edition, yet mass-produced. Hypes can be created, tourist flows can be got going, directed and changed. A classic illustration of this happening is Don de Lillo’s hilarious spoof about a tourist attraction known as “the most photographed barn in America.” As he tells the story in his deadpan way, he takes a young colleague who has joined his department of Hitler Studies in Blacksmith, a god-forsaken little college town somewhere in the mountain West. “We drove twenty-two miles into the country around Farmington. There were meadows and apple orchards. White fences trailed through the rolling fields. Soon the signs started appearing. THE MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA. We counted five signs before we reached the site. There were forty cars and a tour bus in the makeshift lot. We walked along a cowpath to the slightly elevated spot set aside for viewing and photographing. All the people had cameras; some had tripods, telephoto lenses, filter kits. A man in a booth sold postcards and slides – pictures of the barn taken from the elevated spot. We stood near a grove of trees and watched the photographers. Murray - the narrator’s young colleague – maintained a prolonged silence, occasionally scrawling some notes in a little book. “No one see the barn,” he said finally. A long silence followed. “Once you’ve seen the signs about the barn, it becomes impossible to see the barn.” He fell silent once more. People with cameras left the elevated site, replaced at once by others. “We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura. Can you feel it, Jack? An accumulation of nameless energies.” There was an extended silence. The man in the booth sold postcards and slides. ‘Being here is a kind of spiritual surrender. We only see what the others see. The thousands that were here in the past, those who will come in the future. We’ve agreed to be part of a collective perception. This literally colors our vision. A religious experience in a way, like all tourism. Another silence ensued. “They are taking pictures of taking pictures,” he said. He did not speak for a while. We listened to the incessant clicking of shutter release buttons, the rustling crank of levers that advanced the film. “What was the barn like before it was photographed?” he said. “What did it look like, how was it different from other barns, how was it similar to other barns? We can’t answer these questions because we’ve read the signs, seen the people snapping the pictures. We can’t get outside the aura. We’re part of the aura. We’re here, we’re now.”

He seemed immensely pleased by this.” 12

This is probably as good an evocation as any of the pleasures of post-modernism. It is a matter of a second-order pleasure, derived from going with the flow, from doing as others do, from waiting in line to take the same picture as others just did, yet at the same time reaching transcendence, seeing yourself in the crowd, yet as if from a distance. There is a double vision involved, and a dose of irony thrown in for free. This takes us one step further than De Lillo: We are part of the aura, yet we can also at the same time step outside it. And photography is there to prove it. A beautiful illustration of this is offered by a classic photograph taken by Lee Friedlander. 13 The tourist scene it shows is Mount Rushmore, photographed from many angles, in many reflections, blurring inside and outside. These are people who, as De Lillo would have it, are all part of the aura, all here, all now. Yet Friedlander’s photograph has become a critical ingredient in our enjoyment of the moment. He deconstructs reality for us, decomposing it into mirrorlike reflections of reflections; as in an early Cubist phantasy, he produces an ironic comment and gives us pleasure. Friedlander adds the layer of photography to the mirrorlike layers that he had chosen to photograph; the entertainment he offers is not unlike the awe we feel when confronted with the circus act of a man keeping cups and saucers up in the air. Such are the joys and pleasures offered by the asinine forms of contemporary mass tourism, if we allow ourselves to transcend it, and becoming its ironic observers. All we need to do is develop an eye and an ear for it. If Kilroy can do it, why can’t we?

Well, for one thing, as the first half of my story may remind us, the commodification paradox will keep us from over-indulging in the pleasures of post-modernity. It may serve as a sobering reality check. Admittedly, the pleasures of post-modern tourism, as here described, all have an undeniable high-brow touch, a whiff of elitism, about them. Particularly in their armchair variety where the joy lies in versions of inner, imaginary, travel, as almost a form of escapism, a form of inner emigration. At any rate, it will always be a joy for an elite and will never be able to rival the immediate exhilaration and excitement of contemporary mass tourism, from snow mobiles racing through Yellowstone Park or masses of down-hill skiers laying waste to fragile mountain meadows. Over-tourism as a force devastating every object of mass-longing is here to stay, it seems, offering no escape.

Whatever glimmers of hope there are may be too late. Movements of resistance may be gestating, centering on issues of ecological sustainability, rallying support around shared feelings of shame and guilt. Buzzwords are spreading like wildfire over the Internet, words like flight shame, originating in Sweden, are exerting downward pressure on air travel, inspiring people to reduce their carbon footprint. Even in consumer hotbeds like China, climate consciousness is on the rise. It enjoys an Instagram-fueled tailwind from successful campaigns against plastics. A global movement is gaining momentum that grants legal personhood to rivers, lakes, forests and mountains. In its American iteration the movement takes a leaf, ironically, from the long-standing corporate practice that turns corporate entities into legal persons, giving them a voice and having them speak on behalf of corporate interests. This time environmentalism is in command, speaking on behalf of threatened eco-systems, such as lakes and valleys. A recent case is the Lake Erie Ecosystem Bill of Rights, adopted by 61% of the voters in a February, 2019, referendum, granting the Lake Erie ecosystem legal personhood, with all consequent rights in law, including the right “to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve.” It joined other more-than-human entities accorded legal personhood, in India, New Zealand, the Colombian Amazon and Ecuador. All such recent legal moves have come to be known as the “natural rights” or “rights of nature” movement. 14

Whether such movements, and the changes in the ways people think and behave about the environment, are enough to fend off the worst-case environmental scenarios, we cannot tell. Doomsday scenarios may still appear more likely outcomes, with tourism no more than an echo from a time before the ultimate cataclysm. Again, De Lillo may help us to conjure this up in our minds. Having given us a taste of the post-modern pleasures of travel in his passages about the most-photographed barn in its quasi-Arcadian setting, the setting changes to one where cataclysm has struck. We enter familiar De Lillo terrain, as in his Cosmopolis , or Falling Man. In an inspired moment the story line turns back on itself - with the central characters fleeing from the toxic cloud that hangs over Blacksmith, leaking from a derailed tank car in the railroad yard - they pass a road sign, pointing them to the most photographed barn in America. Tourism has overnight turned into a flight for one’s life, in a nightmare world reminiscent of literary evocations like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road or Jonathan Raban’s Surveillance. 15 No more postmodern pleasures to be had here, nor are any on offer.

is professor emeritus and former chair of the American Studies program at the University of Amsterdam, where he taught until September 2006. He is Honorary Professor of American Studies at the University of Utrecht and is a past president of the European Association for American Studies (EAAS, 1992–1996). He is the founding editor of two series published in Amsterdam: Amsterdam Monographs in American Studies and European Contributions to American Studies .

1 Henry James, The American Scene, quoted from etext of The American Scene (London, Chapman & Hall, ltd., 1907), at http://www2.newpaltz.edu/~hathawar/americanscene2.html . Last accessed January 4th, 2020, pp. 84,85.

2 Rene Chun, “The Dutch War on Tourists,” https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/09/the-war-on-tourists/594766/ . Last accessed January 4th, 2020.

3 Lawrence N. Powell, New Orleans: An American Pompeii? In: Reinhold Wagnleitner, ed., Satchmo Meets Amadeus (Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2006) 147.

4 John Taliaferro, Grinnell: America’s Environmental Pioneer and His Restless Drive to Save the West. (New York: Liveright/Norton, 2019).

5 Bill Bryson, A Walk in the Woods : Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail (New York: Broadway Books, 1998); Jonathan Raban, Hunting Mr Heartbreak (London: Collins Harvill, 1990).

6 Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday (translated from German by Anthea Bell) (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013).

7 Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer, Grand-Hotel Europa (Amsterdam: Arbeiderspers, 2019) References – in brackets – are to pages in the Dutch version. Translations are mine.

8 Michiel van Erp, Pretpark Nederland (TV documentary, VPRO Television, 2006).

9 Tony Perrottet, Pagan Holiday: On the Trail of Ancient Roman Tourists (New York: Random House, 2003).

10 Perrottet, as quoted in Chun, The Atlantic (cf. footnote 2, above).

11 Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes Tropiques (1955) London: Penguin Books, 1992 (translation by John Weightman, and Doreen Weightman; Introd. and Notes by Patrick Wilckens) pp. 43, 44, 45.

12 Don DeLillo, White Noise (1984) London: Picador, 2011, quotations from pp. 13-15, 30.

13 Go to https://sites.middlebury.edu/landandlens/2016/10/16/lee-friedlander-mt-rushmore-south-dakota-1969/

14 Robert MacFarlane, “Should this valley have rights?”, The Guardian Weekly, 8 November 2019 ( https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/nov/02/trees-have-rights-too-robert-macfarlane-on-the-new-laws-of-nature ) Also: Stone, Christopher D., “Should Trees Have Standing? Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” Southern California Law Review , 45 (1972): 450-501 For a discussion of the rise of corporate legal persons and their disembodied voices, see my “The Revenge of the Simulacrum: The Reality Principle Meets Reality TV,” Social Science and Modern Society , 56, 5, (September/October 2019): 419-427.

15 Cormac McCarthy, The Road (New York: Random House, 2007), Jonathan Raban, Surveillance (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 24 June 2019

Shifts in tourists’ sentiments and climate risk perceptions following mass coral bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef

- Matthew I. Curnock ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2365-810X 1 ,

- Nadine A. Marshall 1 ,

- Lauric Thiault ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5572-7632 2 , 3 ,

- Scott F. Heron ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5262-6978 1 , 4 , 5 ,

- Jessica Hoey 6 ,

- Genevieve Williams 1 , 6 ,

- Bruce Taylor 7 ,

- Petina L. Pert ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7738-7691 1 &

- Jeremy Goldberg 1 , 8

Nature Climate Change volume 9 , pages 535–541 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

55 Citations

53 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate-change impacts

- Psychology and behaviour

Iconic places, including World Heritage areas, are symbolic and synonymous with national and cultural identities. Recognition of an existential threat to an icon may therefore arouse public concern and protective sentiment. Here we test this assumption by comparing sentiments, threat perceptions and values associated with the Great Barrier Reef and climate change attitudes among 4,681 Australian and international tourists visiting the Great Barrier Reef region before and after mass coral bleaching in 2016 and 2017. There was an increase in grief-related responses and decline in self-efficacy, which could inhibit individual action. However, there was also an increase in protective sentiments, ratings of place values and the proportion of respondents who viewed climate change as an immediate threat. These results suggest that imperilled icons have potential to mobilize public support around addressing the wider threat of climate change but that achieving and sustaining engagement will require a strategic approach to overcome self-efficacy barriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

When, where, and which climate activists have vandalized museums

Lily Kinyon, Nives Dolšak & Aseem Prakash

Experience exceeds awareness of anthropogenic climate change in Greenland

Kelton Minor, Manumina Lund Jensen, … Minik T. Rosing

Building eco-surplus culture among urban residents as a novel strategy to improve finance for conservation in protected areas

Minh-Hoang Nguyen & Thomas E. Jones

Global warming threatens ecosystems and societies globally. However, in many countries public attitudes and perceptions of climate risks have lagged behind the accumulation of scientific evidence and assessments, contributing to inadequate political support for mitigation or adaptation 1 , 2 , 3 . As the risks and costs of climate change will increase the longer mitigation is delayed 4 , there is a need to understand barriers to public engagement with the issue and support for public action, including drivers of risk perceptions.

Many contextual and cultural factors can influence individuals’ climate change beliefs and attitudes, including value orientations, social identity and group norms 5 . While acceptance of the scientific consensus on human-induced climate change has been identified as an important ‘gateway belief’ to increased support for climate actions 6 , simply presenting more scientific facts to a sceptical or unengaged audience can be ineffective and even counterproductive 7 . Changing attitudes, beliefs and value orientations requires both cognitive and affective engagement (that is, reasoned understanding combined with emotional consequence), with emotion regarded to have the greater influence 3 , 8 , 9 . Yet failure to elicit an affective response to the threat of climate change is common among climate and behaviour change campaigns 10 . Part of this problem is a widespread perception that climate change is an abstract threat, with distant impacts that are presumed to affect other people, in other places at a future time 11 , 12 , 13 .

Research that seeks to understand the processes by which climate change risks become more salient to people has become an important field of enquiry. Climate change awareness and risk perceptions can be influenced through affective stimuli and the emotional responses associated with the perceived threat of loss or harm to oneself and/or things that are valued 5 , 14 . The effectiveness of emotional appeals and of evoking specific emotions to promote public engagement in environmental issues and behaviour change is an ongoing subject of scholarly debates 15 . Discrete emotions that have been identified as strongly associated with increased support for climate change policy include worry, interest and hope 14 . Eliciting fear can result in attitudinal changes and motivate new behaviours in response to a perceived threat 15 , 16 ; however, fear has also been shown to negatively influence engagement with the climate change issue and is considered detrimental to self-efficacy (the belief in one’s ability to affect change) 9 , 14 , 17 .

One approach to fostering improved engagement with climate change is the use and portrayal of icons. Icons are potent in their appeal to personal values and emotions; as such, they play an important role in representing climate change 18 , 19 . Iconic entities, including various animals, plants, natural and human-made landmarks, landscapes and ecosystems are symbolic, highly valued in numerous ways, and are synonymous with national and cultural identities 20 . Climate icons have been defined as “tangible entities which will be impacted by climate change, which the viewer considers worthy of respect, and to which the viewer can relate and feel empathy” 17 . Studies on the affective appeal of climate icons have used focus groups and workshops to identify characteristics that contribute to higher engagement 9 , 17 , 18 . However, affective responses associated with a large-scale climate impact to an iconic entity have not previously been documented.

In addition, an emerging body of literature on the ‘science of loss’ has highlighted an increasing need for research that explains the range of human values associated with the natural world, and how these values are endangered by a changing climate 21 , 22 . While the prospect of icons becoming damaged or degraded might prompt evaluations of tangible and direct economic losses, there are many intangible and non-economic values for icons that are likely to remain insufficiently accounted for (for example, cultural, lifestyle, health and identity values) 22 . The incomplete recognition of these intangible values, and of how heterogeneous communities will be affected by an icon’s loss or damage, increases the risk of failure to anticipate limits to adaptation, and to distinguish between acceptable, tolerable and intolerable outcomes 22 , 23 .

The Great Barrier Reef (GBR) is an iconic ecosystem and is regarded as Australia’s ‘most inspiring’ icon 24 . It is part of the national cultural identity and its UNESCO World Heritage status is a source of pride for most Australians 24 , 25 . Place attachment, pride and place values (for example, aesthetic, biodiversity, scientific heritage and lifestyle values) for the GBR extend to communities of stakeholders internationally 26 , 27 and contribute to the GBR’s appeal as an international tourism attraction 28 . Physical and aesthetic attributes of the GBR that motivate tourists to visit and that contribute to their satisfaction with reef-based activities (for example, snorkelling, scuba diving and wildlife watching), include the perception of healthy corals, abundant fish and clear water 29 . Tourism has become the GBR’s largest direct economic contributor, providing more than 58,000 sectoral jobs (full-time equivalent) and generating an estimated AUD$5.7 billion annually; the GBR’s total economic, social and icon asset value has been estimated at AUD$56 billion 30 .

However, the GBR faces multiple, cumulative threats, including climate change, and its long-term outlook has been assessed as poor and getting worse 31 . The 2016 marine heatwave caused the most intense coral bleaching observed on the GBR and resulted in an estimated 29–30% loss of shallow coral cover 32 . The following summer, unprecedented back-to-back coral bleaching caused an estimated 20% of additional coral mortality 33 . Most of the severe bleaching occurred in the northern half of the GBR Marine Park, affecting many tourism sites in the Cairns region 34 . Additionally, in March 2017, a severe tropical cyclone damaged reef and island tourism sites in the Whitsundays region 35 . Future projections of heat stress under a business-as-usual scenario (representative concentration pathway RCP 8.5) represent an existential threat to the GBR and to coral reefs globally, with severe coral bleaching expected to occur annually from the mid-2040s (ref. 36 ).

News of impacts to the GBR over 2016–2017 were reported internationally and a large proportion of those media stories were sensationalized and fatalistic in their messaging 37 . There were concerns that this negative media coverage would lead to a decline in tourist visits to the region 38 and propagate perceptions that no effective action to save the GBR is possible 37 . Records of visits to the GBR indicate that general decline in tourist visits has not yet occurred 39 ; instead, there has been an increase in ‘last chance tourism’, characterized by the motivation to see an iconic place (or species) before it is gone or permanently changed 40 .

In this study, we present results from surveys of 4,681 tourists (53% Australian and 47% international) who visited the GBR region before and after the events of 2016–2017 described above (see Methods ). We show that imperilled icons can contribute to proximizing the climate change issue across scales by comparing tourists’ affective responses and place values associated with an icon, their perceptions of threats to those values and their protective sentiment and self-efficacy, before (2013, n = 2,877) and after (2017, n = 1,804) the icon was subjected to a large-scale climatic impact.

Emotional responses to the GBR

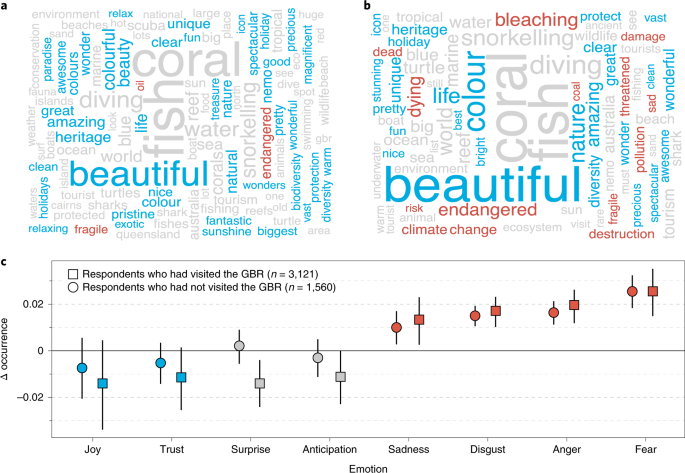

We found a significant increase in the use of negatively valenced emotional words from 2013 to 2017 in response to the open-ended question, “what are the first words that come to mind when you think about the GBR?” (Fig. 1a,b ). In particular, words associated with sadness (for example, ‘fragile’ and ‘disappointing’), disgust (for example, ‘pollution’ and ‘ruined’), anger (for example, ‘destruction’ and ‘damage’) and fear (for example, ‘change’ and ‘danger’) increased significantly, while words evoking neutral or positive emotions did not change (Fig. 1c ). We compared the use of emotive words provided by tourists who had visited the GBR ( n = 3,121) with words of those who had not visited the GBR at the time they were surveyed ( n = 1,560). There was no difference in the use of such words between the two groups (Fig. 1c ), suggesting that the emotive response was not dependent on personal experience and observation of GBR impacts.

a , b , Visual comparisons of “the first words that come to mind when you think of the GBR” among tourists in the GBR region in 2013 ( n = 2,877) ( a ) and 2017 ( n = 1,804) ( b ). The size of words represents the relative frequency of responses. Words with positive and negative valence are coloured in blue and red, respectively. Neutral words are shown in grey. Words occurring fewer than three times are omitted. c , Mean change in occurrence of positive (blue), negative (red) and neutral (grey) emotions associated with responses from 2013 to 2017 in respondents who had visited the GBR ( n = 3,121) compared with those who had not ( n = 1,560). Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Changes in the occurrence of specific emotions are significant if the confidence interval does not overlap with the 2013 (zero) baseline.

Elements of the negative emotional content of responses in 2017 (Fig. 1b,c ) were consistent with ‘ecological grief’, characterized as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change” 41 . Sadness, anger and fear are common emotional reactions to many different types of loss, contributing to diverse grief responses 42 . Disgust is a primitive behaviour-influencing emotion that also occurs in a variety of contexts, including in response to politically oriented stimuli 43 . Ecological grief is increasingly being recognized among the unquantified and intangible costs of ecological losses associated with the Anthropocene 41 , 44 , 45 . A related study reported ‘reef grief’ as a response to the 2016–2017 GBR coral bleaching event among local coastal residents and tourists, and found that ratings of place attachment, place identity, place-based pride, lifestyle dependence and derived wellbeing are associated with stronger expressions of ecological grief 46 . Our results here (Fig. 1 ) provide further insights into the emotional manifestation of ecological grief in this context. As non-local actors, tourists would not normally be considered to have strong lifestyle dependence on the destinations and attractions they visit; however, their place attachment for an icon such as the GBR can still be strong 25 , 26 and they are vulnerable to experiencing grief in response to the icon’s loss or damage.

Threat perceptions and climate change attitudes

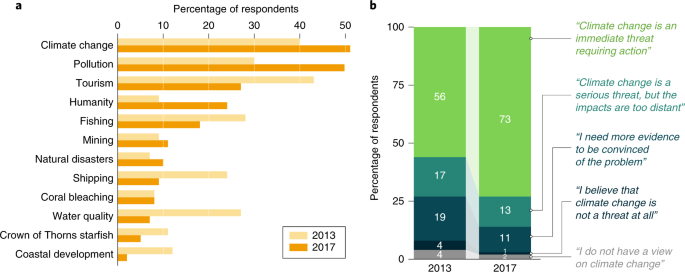

In short, open-ended responses to the question “what do you think are the three most serious threats to the GBR?”, the proportion of respondents identifying climate change increased from 40% of respondents in 2013 to 51% in 2017, making climate change the most frequently cited threat overall in 2017 (Fig. 2a ). In comparison, in 2013 the most commonly identified threat to the GBR was tourism (43% of respondents), which dropped to third-ranked in 2017 (27% of respondents). The pollution category included a wide range of responses (for example, litter, marine debris and urban pollutants) and was identified in 2017 by 50% of respondents. In 2017, pollution ranked second: up from being ranked third in 2013 at 30%, potentially reflecting an increased awareness of the threat of marine debris. The other category that displayed a notable increase was effects of humanity (9% in 2013 to 24% in 2017), which included responses such as overpopulation, human activity and anthropogenic threats. Coral bleaching was cited by 8% of respondents in both years; however, its ranking relative to other perceived threats increased from eleventh in 2013 to ninth in 2017.

a , The percentages of tourists in 2013 ( n = 2,877) and 2017 ( n = 1,804) who identified specific threats among their perceived “three most serious threats to the GBR”. The top 12 response themes are shown for each group. b , The percentages of tourists in 2013 ( n = 2,877) and 2017 ( n = 1,804) choosing each of five statements to represent their awareness and attitude towards climate change.

Public perceptions of environmental risks and threats are shaped by social, cultural and psychological processes, and the exchange of information about ‘risk events’ can amplify (or attenuate) public responses to a risk or threat 47 . Symbols and imagery portraying risk events further interact with these processes in ways that can intensify risk perceptions 48 . Public awareness and perceptions of threats facing the GBR have evolved in recent decades and media representations of threats and risk events are considered to have had influence 37 , 49 . Ironically, tourists perceive their own activities as a dominant impact at ecologically sensitive sites 50 . The presence of other tourists, associated infrastructure and localized site degradation are often the only pressures and impacts readily visible and identifiable at tourist sites, thus influencing visitors’ wider threat perceptions 51 . While tourism has not been recognized in any recent scientific literature as among the most serious threats to the GBR, our results suggest that in 2013 many GBR tourists were probably unaware of the level of risk associated with other, scientifically recognized, threats such as climate change; and that any effects that could be attributed to such threats were less (or were not) visible to GBR tourists at that time.

There was a marked increase from 2013 to 2017 in the proportion of tourists who reported their acceptance that “climate change is an immediate threat requiring action” (56 to 73%; Fig. 2b ). While this proportion for international tourists (increasing from 64% in 2013 to 78% in 2017) was higher than that for Australians (increasing from 50% in 2013 to 67% in 2017), the magnitude of this increase in both groups towards recognition of the climate change threat, its immediacy and the need for action, represents a substantial shift in normative attitudes toward climate change at a scale and in a timeframe not reported in previous studies. Previous annual surveys of Australian attitudes towards climate change, over the period from 2010 to 2014, showed that while the attitudes of individuals fluctuated, the aggregate levels of opinion remained stable over that time 52 . Whether the observed changes in 2017 represent a reaction at a moment in time or a lasting change in attitudes is uncertain and further work is needed to determine whether these perceptions have become normalized in the wider population.

While we cannot conclusively attribute the cause of this attitudinal change to the GBR coral bleaching events, we believe that a strong influence and ‘risk amplification’ was likely, considering the scale of the event, its extensive media coverage that explicitly attributed the events to climate change 37 , associated imagery, as well as the direct observation of affected reef sites by many tourists who visited the GBR over this time. While the more sensationalized and fatalistic media stories of the coral bleaching events and the GBR’s imperilled status have been criticized for their potential to cause public disengagement and a loss of hope in mitigation actions 37 , the broader exchange of information precipitated by this risk event may have had positive outcomes on public threat awareness (Fig. 2a ) and support for mitigative action (Fig. 2b ).

Personal experience and perceptions

We found significant declines in tourists’ perceptions of the GBR’s aesthetic beauty, their overall satisfaction with their experience of the GBR (among those who had visited) and in their ratings of the quality of reef tourism activities (among those who had participated; Table 1a ). While the 2017 mean scores remained relatively high on a 10-point scale (ranging between 7.46 and 8.52), there is an inherent positivity bias associated with tourist satisfaction ratings and relatively small changes can signal a qualitative distinction 53 .

The aesthetic appreciation of natural settings is a fundamental way in which people relate to the environment, and aesthetic perceptions play a critical role in the satisfaction that tourists derive from places 54 . In a coral reef setting, physical attributes that have been correlated quantitatively with non-expert ratings of aesthetic beauty include water clarity, fish abundance and ‘coral topography’ (the complexity of coral formations and features); however, many more visual and sensory attributes contribute to people’s overall aesthetic appraisal 54 . Imagery associated with the mass coral bleaching events was widely featured in media articles, in which aerial and underwater scenes of white, pale and fluorescent corals were often depicted (for example, see the March 2017 cover of Nature 55 ). Such imagery is visually striking, and scenes of bleached coral gardens can even be considered beautiful 56 . Such scenes are typically short-lived: once mortality occurs, brown algae quickly smothers coral skeletons 57 . While the biological process of coral bleaching is complex and its explanation is technical, the imagery from the event may have been highly engaging to non-expert audiences, overcoming barriers that have been associated with ‘expert’ conceptualizations of climate change threats and impacts 18 .

At the time of the 2017 tourist survey (July–August), bleached coral was still present in low levels; however, mortality associated with the 2016 coral bleaching event had already occurred from Cairns to the far north of the GBR, and cyclone-damaged reefs and islands in the Whitsundays region had not recovered 58 . We therefore consider that a substantial proportion of the 1,076 respondents who had visited the GBR when surveyed in 2017 probably had personally experienced and observed affected areas, influencing their aesthetic perceptions and satisfaction. However, as noted above, the personal observation of impacts on the GBR was not a requisite for recalling a negative emotional response to the GBR (Fig. 1c ).

Effects on place values, pride and identity

Understanding place values, which represent the estimated worth and meaning of a place, is important for environmental management and decision making 59 , 60 . We found that strong, shared values for an icon are responsive to ecosystem disturbances and threats. In contrast with the declines in ratings of GBR perceptions and the tourist experience reported above, we found small but significant increases from 2013 to 2017 in ratings of values attributed to the GBR, including its biodiversity value, scientific and education value, lifestyle value and international icon value. Similarly, pride and identity associated with the GBR were significantly higher in 2017 (Table 1b ). Pride in the GBR and GBR identity were positively correlated with these cultural values attributed to the GBR (see Table 2 ). Place values, such as those recorded for the GBR’s biodiversity, scientific heritage and lifestyle values, are consistently strong among diverse stakeholder groups (geographically proximate and distal alike), whereas greater variability is expressed for pride and identity 27 , consistent with the lower mean scores for GBR identity among tourists (Table 1b ).

We propose that these increased ratings for (or expressions of) place values, identity and pride are complementary to the expression of ecological grief (representing ‘ecological empathy’), and form part of the holistic affective response to an imperilled climate icon. Empathy for nature stems from a recognition of its intrinsic value and a feeling of connectedness to it (for example, pride and identity) 61 and the desire to protect the environment has been proposed as an extension of Maslow’s ‘values of being’ in the self-actualization process 61 . Knowing that such values can change in response to environmental change highlights a need for their continued assessment. As loss and ecological grief are expected to become increasingly common responses to climate impacts 21 , 41 , the health literature on cumulative trauma suggests that ‘compassion fatigue’ 62 and the erosion of ecological empathy (or ‘environmental numbness’) 63 may occur.

Protective sentiment and self-efficacy

While protective sentiment associated with the GBR increased significantly in 2017, including tourists’ willingness to act and willingness to learn (Table 1c ), there was a corresponding decline in self-efficacy, represented here by capacity to act and optimism for the future of the GBR. The slight increase in ratings for sense of agency and opportunity to act indicates some self-awareness of the individual’s role in mitigating threats. However, the corresponding decline in sense of individual responsibility suggests that community expectations of responsibility and capacity for addressing great threats such as climate change are located in the actions of governments and corporations, rather than their own actions.

Conclusions

Our study identified a clear affective response amongst tourists, whose protective sentiment for the GBR became heightened after a notable climate impact, while their sense of self-efficacy diminished. Concomitant with grief-associated emotive responses (sadness, anger and fear; Fig. 1c ), respondents expressed empathy for the icon through increased ratings of place values, identity and protective sentiment (Table 1a,b ).

While our study is limited to tourists, we note that they represent diverse national and international stakeholder interests, attitudes and values, from widespread places of origin. Their affective responses in this case were not dependent on visits to the GBR and personal experience of impacts (Fig. 1c ), indicating other contributing influences; for example, sensationalized media representations 37 and imagery of the coral bleaching event. This suggests that representations of icons like the GBR, when subject to a high-profile risk event, can elicit wide-reaching affective responses, amplify risks and proximize the climate change issue. However, like other examples of the iconic approach for representing climate change 9 , 18 , the observed decline in self-efficacy represents a barrier to productive engagement in mitigative actions. In particular, the expression of fear (Fig. 1c ) and the observed decline in individual sense of responsibility (Table 1c ) may be indicative of the perceived scale of the climate threat and the intractability of the problem through individual efforts alone. Nonetheless, the expressions of protective sentiment in this context suggest a significant potential to mobilize public support around addressing threats to icons, like the GBR, where opportunities for individual action are linked to a broader, collective response.

From an action perspective, our findings can be considered both potentially constraining (due to reduced self-efficacy) and enabling (due to increased protective sentiment). Management, scientific or conservation agencies that seek to engage communities in climate mitigation and adaptation may arouse high levels of interest and empathy by using evocative imagery of icons during crises or high-profile events. However, achieving and sustaining engagement in collective action will require a more strategic and thoughtful approach to overcome efficacy barriers. Prevailing over such barriers can potentially be achieved by drawing on lessons from health and psychology literature, including, for example, the ‘small changes’ approach 64 , positive affirmation and promotion of incremental successes 65 , and fostering pride in pro-environmental behaviours 66 . Maintaining hope, balanced with clear and accessible actions linked to attainable goals, also remains critical to motivating people and sustaining their engagement in collective efforts to restore, mitigate and adapt 63 , 67 .

Engaging with loss and grief represents an additional challenge that requires sensitivity. An understanding of shared place values provides an important basis for constructive engagement with the possibility of loss, and appealing to such values can empower communities and motivate cooperation to offset potentially harmful outcomes 21 , 22 . However, it is important to recognize that wider place values are heterogeneous, that some may be in conflict, and that respectful, transparent dialogue provides the best avenue to negotiate areas of contention 68 .

Our study provides insights into some of the shared place values assigned to the GBR among one, albeit diverse, non-local stakeholder group. As a multiple-use marine park and World Heritage area, with adjacent coastal communities dependent on tourism, fishing, agriculture and mining (among other industries), and with cross-scale communities deriving wellbeing from a broad range of cultural and ecosystem services, the GBR represents an important example among climate icons that encapsulates a multiplex of human values that are challenged by climate change. Like other natural World Heritage-listed sites, the full extent of cultural and other intangible values that are at stake in the GBR remains poorly understood 31 . Research to describe the diversity and importance of human values associated with iconic places that are vulnerable to loss is needed, as a precursor to predicting how such values might respond to future losses, to guide coordinated responses to the climate threat and to mitigate potential suffering from future impacts 21 , 22 .

Survey design

To measure and compare tourists’ perceptions and values of the GBR and protective sentiments for the GBR, we used a series of statements from an established framework for monitoring human–environment cultural and place values 27 and asked survey respondents to indicate their level of agreement/disagreement on a 10-point scale (1 = very strongly disagree; 10 = very strongly agree). Similarly, we asked respondents who had visited the GBR to provide ratings of their satisfaction (1 = extremely dissatisfied; 10 = extremely satisfied) and the quality of popular reef-based activities (1 = very low quality; 10 = very high quality) if they had undertaken them during their visit. Climate change threat awareness and perceptions were elicited by asking respondents to select one statement from five options that best reflected their viewpoint: (1) “climate change is an immediate threat requiring action”, (2) “climate change is a serious threat but the impacts are too distant for immediate concern”, (3) “I need more evidence to be convinced of the problem”, (4) “I believe that climate change is not a threat at all” and (5) “I do not have a view on climate change”. To elicit threat perceptions, respondents were asked to list what they thought were the “three most serious threats to the GBR” in a short, open-ended format. While some minor changes were made to the overall survey instrument between 2013 and 2017, the questions used for our analyses in this study remained identical.

Data collection

Tourists in the GBR region (defined as the GBR catchment, bounded by Cape York in the north, Bundaberg in the south and the Great Dividing Range in the west) were surveyed using face-to-face interviews between June and August in both 2013 and 2017 (ref. 69 ). For the purposes of this study we defined tourists broadly as non-resident visitors to the GBR region. The surveys were conducted at 14 regional population centres along the coast, in public locations such as beaches, boat ramps, parks, shopping centres and markets, and on a limited number of GBR tourism vessels. Interviews were conducted by trained survey staff, and responses were entered in situ into tablet computers, using the iSurvey application. In 2013, we achieved a sample of 2,877 tourists (1,557 of whom were Australian, 1,286 from overseas and 34 respondents who did not provide their place of origin), followed by a sample of 1,804 tourists in 2017 (831 Australian, 805 from overseas and 168 respondents who did not provide their place of origin). Our sampling strategy used a combination of convenience and quota sampling 70 , to minimize potential biases for gender, age and nationality. However, a limitation of the study was its availability in English only, and we acknowledge that some non-English-speaking tourist market segments are under-represented (for example, tourists from China). This research involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the CSIRO Social Science Human Research Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). All respondents gave informed consent to participate in the voluntary survey.

Description of sample

The demography and location of origin for both domestic and international tourists was comparable between years; however, in 2017, the mean age of domestic tourists was lower than that for 2013 (43.5 ± 0.45 yr compared with 48.9 ± 0.64 yr respectively). A higher proportion of females was represented among the international tourists in both years (55% of our sample in 2013 and 57% in 2017). Overseas respondents came from 54 countries in our 2013 sample and 35 countries in our 2017 sample. Most international respondents came from Europe and North America, with the largest proportions originating from the United Kingdom (25% in 2013 and 19% in 2017), Germany (18% in 2013 and 19% in 2017), France (12% in 2013 and 11% in 2017) and the United States (8% in 2013 and 11% in 2017). Most domestic tourists were repeat visitors to the GBR region (77% in both years), while most international tourists were first-time visitors to the region (84% in 2013 and 86% in 2017). Among domestic tourists, 58% in both years had visited the GBR during their stay in the region; among international tourists, 85% had visited the GBR in 2013 and 67% had visited the GBR in 2017. The number of responses ( n ) varied for some of the survey questions (for example, ratings of the quality of scuba diving, snorkelling and wildlife watching were limited to respondents who had participated in those activities); where relevant, these differing sample sizes are shown (Table 1 ), with accompanying standard errors for mean scores.

Statistical analyses of numeric data

We used MS Excel and SPSS (v.22) software for analyses of numeric data (providing means and comparing the distribution of rating scores for a range of 10-point scaled response questions, as described above). Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-tests (Table 1 ) and Spearman’s rho correlation tests (Table 2 ) were used, as the appropriate statistical tools for ordinal (10-point rating scale) data 71 . Effect sizes ( r ) were calculated manually from the SPSS output z value using: \(r = \frac{z}{{\sqrt {\mit{n}} }}\) .

Word–emotion analysis and word clouds

Our first question in the survey asked, in an open-ended short response format: “what are the first words that come to mind when you think about the GBR?” Responses were cleaned (correcting spelling, removing punctuation and stop words) and their association with eight core emotions theorized by R. Plutchik (fear, anger, joy, sadness, trust, disgust, anticipation and surprise) 72 were scored on a binary scale (0 = not associated, 1 = associated) using the National Research Council of Canada Word–Emotion Association Lexicon (EmoLex) 73 . EmoLex is a large, high-quality, word–emotion lexicon in which more than 14,000 English unigrams (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) and 25,000 word senses were manually annotated by crowdsourcing 74 , noting that multiple emotions can be evoked simultaneously by the same word. We then calculated, for each emotion, the difference in average occurrence (±95% confidence interval) between 2017 and 2013.

To produce the word-cloud visualizations showing basic emotional valence/sentiment associated with words/terms (positive or negative valence shown in blue and red, respectively; Fig. 1a,b ), we adapted EmoLex to account for the contextual relevance of particular words used when referring to a coral reef ecosystem. We removed words that otherwise would have been identified as negatively valenced (for example ‘cold’, ‘sharks’ and ‘wild’) or positively valenced (for example ‘hot’ and ‘warm’) outside this context. New words that we categorized as positively valanced included ‘diversity’, ‘life’, ‘icon’, ‘pristine’, ‘heritage’, ‘colours’, ‘relaxing’, ‘sunshine’, ‘biggest’, ‘vast’, ‘biodiversity’, ‘natural’, ‘nature’, ‘colourful’, ‘unique’, ‘holiday’, ‘holidays’ and ‘relax’. New words/terms that we identified as negatively valanced included ‘bleaching’, ‘bleached’, ‘climate change’, ‘coal’, ‘endangered’, ‘oil’, ‘pollution’ and ‘threatened’. Analyses were done using the {tm} and {syuzhet} packages (for text mining and cleaning and for the word–emotion and word cloud/sentiment analyses, respectively) in R.

Coding of threats

Respondents were asked “what do you think are the three most serious threats to the GBR” in a short open-ended response format. Ranking of the listed threats by respondents was not taken into account. Responses were cleaned and then sorted into main categories, using MS Excel, with coding checked by at least two researchers. Responses in the pollution category included marine debris, beach litter and a range of other contributors, as well as the generic term ‘pollution’. The water quality category included agricultural as well as urban and industrial runoff, sediments and pesticides, while coastal development encompassed port developments, dredging and other industrial activities. The fishing category included all extractive activities, commercial and recreational, illegal foreign fishing and ‘overfishing’ in general. The shipping category included oil spills and ballast water/pollution from shipping. The natural disasters category included responses such as storm damage, cyclones, floods, tsunamis and earthquakes. The climate change category included global warming, rising temperatures (sea and air) and sea level rise. Coral bleaching was coded separately, as was ocean acidification. While climate change, coral bleaching and ocean acidification are related, separate coding of the three terms was considered appropriate. Broad-scale (‘mass’) coral bleaching events result from heat stress, including the recent GBR events, and have been attributed scientifically to climate change 58 , 75 . However, coral bleaching can occur as a result of multiple non-climate change pressures, such as fresh-water inundation and overexposure to direct sunlight 57 . Further to this, heat-stress-induced coral bleaching is only one potential effect (or ‘symptom’) of climate change. Increased storm intensity and/or frequency (physical damage) and sea-level rise (reduced water quality and reef drowning) are other pressures affecting coral reefs that are linked to climate change 76 . Acidification, while associated with climate change as another consequence of increased atmospheric CO 2 absorbed by the ocean, is regarded as a separate driver of many (different) pressures affecting marine ecosystems 76 .

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study (SELTMP 2013; 2017) 69 are publicly available from the CSIRO online data access portal at https://doi.org/10.25919/5c74c7a7965dc . The R code used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Lee, T. M., Markowitz, E. M., Howe, P. D., Ko, C. & Leiserowitz, A. A. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 5 , 1014–1020 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Lacey, J., Howden, M., Cvitanovic, C. & Colvin, R. M. Understanding and managing trust at the climate science–policy interface. Nat. Clim. Change 8 , 22–28 (2018).

Lorenzoni, I., Nicholson-Cole, S. & Whitmarsh, L. Barriers perceived to engaging with climate change among the UK public and their policy implications. Glob. Environ. Change 17 , 445–459 (2007).

Rogelj, J., McCollum, D. L., Reisinger, A., Meinshausen, M. & Riahi, K. Probabilistic cost estimates for climate change mitigation. Nature 493 , 79–83 (2013).

van der Linden, S. L. The social–psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 41 , 112–124 (2015).

van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D. & Maibach, E. W. The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. PLoS ONE 10 , e0118489 (2015).

Wynne, B. Creating public alienation: expert cultures of risk and ethics on GMOs. Sci. Cult. 10 , 445–481 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wood, W. Attitude change: persuasion and social influence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 51 , 539–570 (2000).

O’Neill, S., Boykoff, M., Neimeyer, S. & Day, S. A. On the use of imagery for climate change engagement. Glob. Environ. Change 23 , 413–421 (2013).

Ockwell, D., Whitmarsh, L. & O’Neill, S. Reorienting climate change communication for effective mitigation: forcing people to be green or fostering grass-roots engagement? Sci. Commun. 30 , 305–327 (2009).

Myers, T. A., Maibach, E. W., Roser-Renouf, C., Akerlof, K. & Leiserowitz, A. A. The relationship between personal experience and belief in the reality of global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 3 , 343–347 (2013).